The Arabesque Table

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

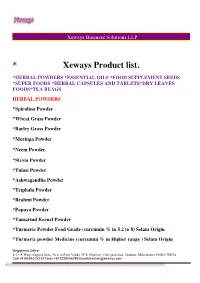

* Xeways Product List

Xeways Business Solutions LLP * Xeways Product list. *HERBAL POWDERS *ESSENTIAL OILS *FOOD SUPPLEMENT SEEDS *SUPER FOODS *HERBAL CAPSULES AND TABLETS*DRY LEAVES FOODS*TEA BEAGS HERBAL POWDERS *Spirulina Powder *Wheat Grass Powder *Barley Grass Powder *Moringa Powder *Neem Powder *Stevia Powder *Tulasi Powder *Ashwagandha Powder *Triphala Powder *Brahmi Powder *Papaya Powder *Tamarind Kernel Powder *Turmeric Powder Food Grade (curcumin % in 5.2 to 8) Selam Origin *Turmeric powder Medicine (curcumin % in Higher range ) Selam Origin Registered Office: L-39/A Wing, Express Zone, Next to Patel Vatika, W.E. Highway, Goregaon East, Mumbai, Maharashtra 400063 INDIA Cell:+919004015233 Telex:+912228406298 Email:[email protected] Xeways Business Solutions LLP *Sunflower Oil Powder *Cloves Powder *Pepper Powder *Black Pepper Powder *Cardamon Powder *Cinnamon Powder *Coriander Powder *Fenugreek powder *Red Chilli Powder *Turmeric Powder *Cumin Powder *Arrow root powder Food Grade *Arrow Root powder Cosmetic Grade *Tapioca Powder *Straw Barry Powder *Pappaya Powder *Pomegranate Powder *Apple powder Registered Office: L-39/A Wing, Express Zone, Next to Patel Vatika, W.E. Highway, Goregaon East, Mumbai, Maharashtra 400063 INDIA Cell:+919004015233 Telex:+912228406298 Email:[email protected] Xeways Business Solutions LLP *Banana Powder *Gauva Powder *Pineaple Powder *Pippal (Long Pepper) *Carob Powder *Aamlaki Powder *Ajmin Powder *Aloevera Powder *Mac Powder *Green Chilli Powder *Pipperment Powder *White pepper powder *Vanila powder * Mango Powder -

Hibiscus Tea and Health: a Scoping Review of Scientific Evidence

Nutrition and Food Technology: Open Access SciO p Forschene n HUB for Sc i e n t i f i c R e s e a r c h ISSN 2470-6086 | Open Access RESEARCH ARTICLE Volume 6 - Issue 2 Hibiscus Tea and Health: A Scoping Review of Scientific Evidence Christopher J Etheridge1, and Emma J Derbyshire2* 1Integrated Herbal Healthcare, London, United Kingdom 2Nutritional Insight, Epsom, Surrey, United Kingdom *Corresponding author: Emma J Derbyshire, Nutritional Insight, Epsom, Surrey, United Kingdom, E-mail: [email protected] Received: 18 Jun, 2020 | Accepted: 10 Jul, 2020 | Published: 27 Jul, 2020 Citation: Etheridge CJ, Derbyshire EJ (2020) Hibiscus Tea and Health: A Scoping Review of Scientific Evidence. Nutr Food Technol Open Access 6(2): dx.doi.org/10.16966/2470-6086.167 Copyright: © 2020 Etheridge CJ, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. Abstract Over the last few decades, health evidence has been building for hibiscus tea (Hibiscus sabdariffa L. Malvaceae). Previous reviews show promise in relation to reducing cardiovascular risk factors, hypertension and hyperlipidaemia, but broader health perspectives have not been widely considered. Therefore, a scoping review was undertaken to examine the overall health effects of hibiscus tea. A PubMed search was undertaken for meta- analysis (MA) and systematic review papers, human randomised controlled trials (RCT) and laboratory publications investigating inter-relationships between hibiscus tea and health. Twenty-two publications were identified (four systematic/MA papers, nine human RCT controlled trials and nine laboratory publications).Strongest evidence exists in relation to cardiovascular disease, suggesting that drinking 2-3 cups daily (each ≈ 240-250 mL) may improve blood pressure and potentially serve as a preventative or adjunctive therapy against such conditions. -

Comes with a Side of Butter Rice Or Bread*

Traditional Dishes 21. *Comes with a side of Butter Rice or Bread* D 1 . M U S A K K A Chicken Lamb Veg $ 2 4 . 0 0 $ 2 6 . 0 0 $ 2 4 . 0 0 Sauteed layer of sliced eggplants and potato, oven-baked, D 1 . with toppings of chicken, lamb or vegetables and melted cheese. D 2 . A L I N A Z I K Chicken Lamb Tasty Turkish lamb or chicken ragout served over a bed $ 2 5 . 0 0 $ 2 8 . 0 0 of eggplant puree. D 3 . L A M B S H A N K ( I N C I K P I L A V ) $ 2 7 . 9 0 Slow cooked and braised in the oven and served with rice and salads. D 2 . D 3 . 22. *All prices exclude 10% service charge* *Comes with a side of Butter Rice or Bread* D 4 . I S K E N D E R Chicken Lamb Doner kebab dipped in Iskender sauce and bread with $ 2 2 . 0 0 $ 2 4 . 0 0 generous topping of yoghurt served with rice or bread. D 5 . D 5 . S U L T A N K E B A B $ 2 4 . 0 0 Mildly spiced lamb served with baked cheese and mashed potato. D 6 . F I R I N K O F T E $ 2 4 . 5 0 Oven baked meat patties in tangy tomato sauce served with rice or bread. D 6 . D 4 . 23. *All prices exclude 10% service charge* Middle East Special 24. M 1 . -

Inspiration Guide Download

Please make sure to read the enclosed Ninja® Owner’s Guide prior to using your unit. HOT & COLD BREWED SYSTEM™ 40 IRRESISTIBLE COFFEE & TEA RECIPES MENU MEDIUM LOOSE TEA FILTERED GRIND LEAF BAGS WATER For the most Brew your favorite Use your favorite Fresh, filtered water COFFEE TEA flavorful coffee, loose-leaf tea and let tea bags, arranging is recommended it’s best to grind the Ninja Hot & Cold the strings so they for the best flavor. CLASSIC/RICH CLASSIC/RICH fresh, whole beans Brewed System™ steep hang outside the Crème De Caramel Coffee 9 Lemon Ginger Chamomile Tea 33 before you brew. We at the right temperature brew basket. Maple Pecan Coffee 10 Zen Green Tea 34 recommend using a to enjoy the best Cinnamon Graham Coffee 11 Lavender London Fog 35 medium grind. possible flavor. Too Good Toffee Coffee 12 Orange Hibiscus Tea 36 Mexican Spiced Coffee 13 OVER ICE/COLD BREW OVER ICE/COLD BREW Watermelon, Mint & Lime Iced Tea 37 Thai-Style Iced Coffee 14 Apple Ginger Sparkling Iced Tea 38 SERVING SIZE NINJA SMART SCOOP™ Double Shot White Russian 15 Pineapple Basil Iced Green Tea 39 THE SCOOP GROUND COFFEE LOOSE LEAF TEA TEA BAGS Cinnamon Caramel Iced Coffee 16 Country Raspberry Sweet Iced Tea 41 2–3 small 1 small 1 tea White Chocolate Hazelnut Iced Coffee 17 Spiced Cranberry Orange Cold Brew Tea 42 ON SCOOPS scoops scoop bag Orange Cream Iced Coffee 18 Cucumber Oolong Cold Brew Tea 44 We’ve included the Ninja Smart 3–5 small 1–2 small 2 tea French Vanilla Iced Coffee 20 Scoop™ for easy, accurate scoops scoops bags SPECIALTY Cold Brew Coffee Lemonade 21 measuring for any size or 3–4 2–3 small 4 tea Toasted Coconut Mocha Cold Brew 22 Hibiscus Lime Tea 45 brew type. -

Karkade' Oseilie De Guinee Guinea Sorrel Karkade' Updated Recipe

Karkade’ Oseilie de Guinee Guinea Sorrel Egypt ……Africa Karkade’ Updated recipe from hibiscus syrup 2 hibiscus flowers, divided 2 Tablespoons hibiscus syrup 1/4 teaspoon vanilla 1-1/2 to 2 cups cold lemon lime soda or sparkling water 8 small blueberries Mint leaves, sprigs 1 tart green apple, sliced thin Raw brown sugar crystals In measuring cup, combine hibiscus syrup with vanilla. Add more syrup if a sweeter drink is preferred. Place 1 hibiscus flower into 2 glasses; spoon 1 Tablespoon syrup into each glass. Add lemon lime soda or sparkling water to fill the glass. Garnish with blueberries, mint leaves and top each glass with sugar crystal glazed green apple slices. Yield: 2 cold tea drinks About the Recipe: A refreshing chilled drink, flavored with sweet hibiscus flowers, brings celebration into one’s life with its refreshing flavor. Just add as much sweet syrup as desired or make this into your favorite cocktail. About the culture: Africa. This popular beverage in Egypt is said to have been a preferred drink of the pharaohs. Throughout history until the present, hibiscus tea has been a preferred beverage in many cultures such as China, Mexico, the Caribbean, and Europe. Many people believe that hibiscus is healthy and cooling since it has no caffeine and yet very refreshing. Most weddings and celebrations in Sudan and Egypt are enjoyed with glasses of ruby red hibiscus tea. Every busy street, train station, bus depot, has its vendors & the dried flowers may be found in every market. Also available recipes for: Jus de Bissap Made from the dried red flowers of Hibiscus sabdariffa, a kind of hibiscus plant, Jus de Bissap (Beesap) seems to be more of a tea than a "juice". -

Tea House Cocktails Wee Drams Edgefield Distillery

TEA HOUSE COCKTAILS EDGEFIELD DISTILLERY Darjeeling Unlimited 10 SPIRITS Joe Penney’s Gin, iced darjeeling bergamot Hogshead Whiskey 9 tea, fresh-squeezed orange & ginger beer Monkey Puzzle 7.75 Piña Delgada 7.75 Three Rocks Rum 8.50 Malibu Rum, coconut water with lime, orgeat Three Rocks Spiced Rum 8.50 & pineapple juice Longshot Brandy 10 Lord Palmer 8.75 Alambic 13 Brandy 13 Earl Grey Infused Vodka, fresh-squeezed Pear Brandy 9 lemon & sugar Edgefield Pot Still Brandy 10.50 Joe Penney’s Gin 8.50 Fuzzy Cheeks 10.75 Coffee Liqueur 6.50 Billy Whiskey, iced pear ginger tea, fresh- Herbal No. 7 7.75 squeezed lime, peach bitters & simple Aval Pota 8.25 Moroccan Mojito 7.75 Spar Vodka 6.50 Moroccan Mint Tea Infused Rum, fresh- squeezed lime & soda water CPR DISTILLERY SPIRITS Frank high proof rum 8.75 Black Mango Lemonade 9 High Council Brandy 8.75 Pimm’s no.1 Liqueur, iced black mango tea, Gables Gin shot 8.50 fresh-squeezed lemon juice & sugar Billy Whiskey 8.75 Ginger Zap 9 Phil Hazelnut Liqueur 6.50 Yazi Ginger Vodka, iced ginger-hibiscus tea, fresh-squeezed lemon juice & honey Floral Fog 11.75 HOUSE FLIGHTS Rose Hip infused Joe Penney’s Gin, Creme De WHISKEY 15 Violette, fresh-squeezed lemon & sugar Hogshead · Billy · Monkey Puzzle Winter’s Breeze Mimosa 9.75 BRANDY 16 fresh-squeezed grapefruit, cranberry & bubbles High Council · Pear · Edgefield Pot Still RUM 14 WEE DRAMS Three Rocks · Three Rocks Spiced · Frank’s High Mama Doblè 4.50 Proof Rum black mango tea infused Three Rocks Rum, LIQUEUR 14 fresh-squeezed lime juice & sugar Aval Pota · Phil · Herbal No.7 El Mariachi 5.50 hibiscus ginger tea infused blue agave tequila, elderflower liqueur, lime & honey syrup HAPPY HOUR beverages served mon-fri 3-6pm McMenamins ales 1 off well drinks 1 off McMenamins wine glass 1 off / bottle 5 off . -

RHS Orchid Hybrid Supplement 2000 September to November

NEW ORCHID HYBRIDS SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER/NOVEMBER 2000 REGISTRATIONS Supplied by the Royal Horticultural Society as International Registration Authority for Orchid Hybrids NAME PARENTAGE REGISTERED BY (O/U = Originator unknown) AËRIDOVANDA New Dawn Aërdv. Mundyi x V. Miss Joaquim W.Morris *AGASEPALUM (Agsp.) Blue Butterfly Zspm. labiosum x Agn. cyanea Exotic Orchids ALANGREATWOODARA Kiwi Gold Z. Kiwi Land x Agwa. Alan R.Tucker ALICEARA Victor Guerra Lorenzen Mtssa. Charles M. Fitch x Onc. Thilo I.Burzlaff ASCOCENDA Dreamcatcher Ascda. Bangkhuntian Gold x Ascda. Guo Chia Long Summerfield Orch.(Kultana) Newberry Blue Skies Ascda. Pudtan x V. Manuel Torres Carter & Holmes Super Cooper Ascda. Fuchs Gold x V. tessellata Orchidopolis(O/U) BALDWINARA Ursula Bdwna. Block Party x Odcdm. Ryoko Miyamoto H.Rohrl BAPTICIDIUM Tsiku Glowworm Onc. Hamana Elfin x Bapt. echinata Tsiku Taiwan Orch. BEALLARA Samba Splendor Bllra. Tropic Splendor x Milt. spectabilis R.Agnes(Aranda Orquideas) BIFRENARIA Trish Rohrl Bif. vitellina † x Bif. atropurpurea H.Rohrl BISHOPARA Youan Me T'nt Ctna. Why Not x Sc. Lana Coryell Taylor Made Orch.(L.Topp) BRASSIA Nectar Brs. bidens † x Brs. lanceana N.& E.Miller(Cape Oasis) BRASSIDIUM Tzeng-Wen Spot Onc. Makalii x Brs. Rex Wong Ching-Tien BRASSOCATTLEYA Deborah Smith C. Lucille Small x Bc. Mount Hood Carter & Holmes Memoria Gerald Lawless C. Picturata x B. digbyana G.Lawless(Lenette) Tsiku Magnolia Bc. Cynthia x C. walkeriana Tsiku Taiwan Orch. BRASSOLAELIA Golden Glory Bl. Richard Mueller x L. tenebrosa H & R BRASSOLAELIOCATTLEYA Blythewood Blc. Emily Simmons x Blc. Kure Beach Carter & Holmes Bon Sweet Blc. Memoria Helen Brown x Lc. -

Product Range Gourmet Teas and Spices

2019 PRODUCT RANGE GOURMET TEAS AND SPICES All blends available for private label! www.buildablend.com Phone: 725-222-9218 Email [email protected] CONTENTS PAGE 2 PAGE AYURVEDIC TEAS PAGE OOLONG TEAS 03 Available as loose leaf, tea bags, ice tea, 26 Available as loose leaf, tea bags, ice tea, and single-serve cups. and single-serve cups. PAGE BLACK TEAS PAGE PU’ERH TEAS 04 Available as loose leaf, tea bags, ice tea, 27 Available as loose leaf, tea bags, ice tea, and single-serve cups. and single-serve cups. PAGE FRUIT TEAS PAGE ROOIBOS TEAS 17 Available as loose leaf, tea bags, ice tea, 28 Available as loose leaf, tea bags, ice tea, and single-serve cups. and single-serve cups. PAGE GREEN TEAS PAGE WHITE TEAS 18 Available as loose leaf, tea bags, ice tea, 31 Available as loose leaf, tea bags, ice tea, and single-serve cups. and single-serve cups. PAGE HERBAL TEAS PAGE SPICES 23 Available as loose leaf, tea bags, ice tea, 33 Available in small and single-serve cups. & large bottles. Packages pictured are for illustration purposes only. Actual package color and style may vary. Due to picking seasons, some blends may not be available until the next picking season. AYURVEDIC TEAS PAGE 3 ANTI-STRAIN BALANCE FASTING TEA GINGER FRESH Due to the full and slightly sweet aroma According to Ayurvedic teachings, this According to Ayurvedic teachings, this Fruity, fresh lemon grass and spicy ginger with a hint of licorice, this blend is an ideal blend is soothing and balancing. -

1 Bottled Iced Teas in America’S Finest Restaurants and Hotels

NEW CALORIE-FREE SWEET BLACK ICED TEA AND CALORIE-FREE SWEET GREEN ICED TEA BY THE REPUBLIC OF TEA --#1 Bottled Iced Teas in America’s Finest Restaurants and Hotels -- NOVATO, CALIF., (April 18, 2011) -- The Republic of Tea announces the addition of two new varietals - - Calorie-Free Sweet Black Tea and Calorie-Free Sweet Green Tea -- to its collection of premium glass bottled iced teas, available now exclusively at fine restaurants and hotels nationwide. NEW Sweet Black Tea is a Calorie Free iced tea brewed from the finest organic black tea leaves and sweetened with stevia leaf. Sweet Black Tea offers a bold, rounded, full-bodied flavor that is very satisfying. NEW Sweet Green Tea is a Calorie Free iced tea brewed from the finest organic green tea leaves and sweetened with stevia leaf. Sweet Green Tea has the freshness and brightness that comes only from pure, brewed iced tea. It possesses a light tropical top note and is slightly fruity on the finish. Stevia leaf (premium leaf, not the common powdered version) is a Calorie-Free , all-natural sweetener with a refreshing taste. As restaurateurs continue to offer their guests more healthful options, without sacrificing quality, style or flavor, new Sweet Black Tea and Sweet Green Tea are perfect additions to the menu. Further, these ready-to-drink pure iced teas are brewed to pair beautifully with the distinctive and diversified cuisine prepared by America’s most distinguished chefs. The complete collection features 12 premium tea experiences including: Raspberry Quince Black Tea , Republic Darjeeling Black Tea , Mango Ceylon Black Tea , Blackberry Sage Black Tea , Ginger Peach Black Tea , Ginger Peach Decaf Black Tea , Pomegranate Green Tea , PassionFruit Green Tea , Açaí Berry Red Tea and new Sweet Black Tea , Sweet Green Tea and Natural Hibiscus Tea . -

Nutritional Properties of Bissap: Health Claims and Evidence

Fibre, Food & Beauty for poverty reduction Nutritional properties of Bissap: health claims and evidence The Bissap plant ( Hibiscus sabdariffa ) has been used in traditional medicine for many centuries, its vivid flowers and calyces often steeped to make a striking red tea. In fact there are a huge number of claims made for Bissap’s therapeutic benefits, from Ayurvedic menstrual remedies 1 to hangover cures and treatments for cancer. As well as its popular appeal as a beverage, hibiscus is clearly regarded as a health drink in many cultures. In the countries of origin, the flowers have been, or still are used as an antiseptic, aphrodisiac, astringent, cholagogue, demulcent, digestive, diuretic, emollient, laxative, cooler, sedative, and tonic! In Chinese folk medicine they are used to treat liver disorders and high blood pressure. In East Africa, the infused hibiscus drink called "Sudan tea", is taken to relieve coughs. 2 However many of these anecdotal benefits have not been subjected to clinical study. Fortunately, extracts of Hibiscus (Bissap) have also been the subject of hundreds of scientific studies, some of these attracting attention from the British media. This summary covers those health claims which are supported in some way by scientific studies or trials. Lowering Blood Pressure High blood pressure (hypertension) afflicts one in three people in Britain. It also increases risks of heart disease by three fold and causes 60 per cent of strokes. In Northern Nigeria Hibiscus drink is traditionally used as a treatment for this condition. 3 Scientific studies indicate that Bissap can indeed lower blood pressure 4 5 and inhibit the angiotension converting enzymes (ACE) that play a part in raising blood pressure 6 7. -

Herbal and Ayurvedic Teas

Bobbi Misiti Yoga & Health Coaching 717.443.1119 www.befityoga.com TEA / O-cha / Te / Chai / der Tee / taj / herbata / ceai / caj Herbal Teas especially are preventative medicine! A very easy way to support your health and your immune system is through drinking herbal teas. Make a habit of each evening making a pot of herbal tea to sip on. Try a morning regimen of turmeric and various herbs each morning — I do both most every day. The picture behind this paragraph is Hanuman carrying a whole mountain of herbs to his sick brother for healing. Herbal and Ayurvedic Teas Herbal Tea …. #1 easy way to use herbs is straight from your garden! Even herbs you don’t think of as teas make powerful medicinal teas. These are simple to make, choose any herb in your garden and pour boiling water over …. Make this part of your evening routine. For example try: Oregano - Great when feeling a cold coming on and for those who have excess candida. Rosemary - Great for our memory :) Yarrow - In tea form yarrow is good for upper respiratory phlegm, reducing fevers, stimulating digestion, and fighting of the common cold, flu, and infections. Tea can also be used for bleeding ulcers, regulating menstruation aiding in reducing cramps and preventing endometriosis, and for anti-biotic purposes. When making tea use a mix of leaves and flowers for a better flavor. Yarrow tea is a great stand alone tea, or for a nice night time tea is to steep 1/2 cup dried yarrow along with some lemon balm for about 17 minutes. -

Roselle – Scientific Name: Hibiscus Sabdariffa L • Menstrual Pain

Roselle – scientific name: Hibiscus sabdariffa L • Menstrual Pain. – Provides relief from cramps and menstrual pain. Anti-Inflammatory and Antibacterial Properties - Aids Digestion. • Weight Loss - Antidepressant Properties - Anti-Cancer Properties. • Cough, Colds and Fever Management - Blood Pressure Management. CPT Roselle Powder, we have eliminated the water which is approximately 85% of the total weight. It is, thereby, naturally concentrated six to seven times. Roselle tea is a mild infusion; you drink the mild infusion and throw the flower (calyse) away. In the case of our Roselle powder capsules you are actually consuming the entire calyse. All benefits, nutritional and otherwise are highly concentrated. Taken as capsules - minimum of 2 per day - 2 to 4 per day would be more beneficial. Roselle, also known as Hibiscus tea has a long tradition of use as a health-supporting drink and food ingredient, and is well known and widely used around the planet. The key to the unique quality, safety, and convenience of Siam Superherbs Roselle powder capsules is our proprietary Cellular Preservation Technology (CPT) freeze dry process. Thailand is known for superior quality Roselle. We start with the high quality Hibiscus sabdariffa that grows and is processed fresh at our doorstep. Our process cannot make the plant better than nature has created it, but it does sustain and deliver all the benefits in a fully-dried, stable, highly concentrated powder that has undergone an aqueous ozone anti-microbial treatment. Roselle is not a fruit or a flower. The edible parts used to make the juice or teas are the “calyces,” the red fleshy sepals that cover and enclose the flower’s seed pods.