Computer-Assisted Analysis of Modern Greek Poetry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HELLENIC LINK–MIDWEST Newsletter a CULTURAL and SCIENTIFIC LINK with GREECE No

HELLENIC LINK–MIDWEST Newsletter A CULTURAL AND SCIENTIFIC LINK WITH GREECE No. 53, October–November 2005 EDITORS: Constantine Tzanos, S. Sakellarides http://www.helleniclinkmidwest.org 22W415 McCarron Road - Glen Ellyn, IL 60137 Upcoming Events Mr. Skipitaris began directing in 1971, at the Off-Broadway Gate Theater in NYC. His credits include productions of Greek The Apology Project classics and plays by Anton Chekhov, Tennessee Williams, On Sunday, October 16, at 3:30 PM, Hellenic Link–Midwest George Bernard Shaw, Neil Simon, Ira Levin, and others. At presents the The Apology of Socrates a presentation by the Lincoln Center’s Alice Tully Hall he directed the World performing arts organizations Theatro and Mythic Media based Premiere of the oratorio Erotocritos, and has staged, among on Plato’s The Apology of Socrates. The event will take place others, the musicals Oklahoma!, Carousel, Of Thee I Sing, and at the Community Hall of the St. John Greek Orthodox Church West Side Story. Mr. Skipitaris’ latest directorial assignment, in Des Plaines, Illinois. the comedy Smile Please!, was recently performed at the Hellenic Cultural Center theatre in Long Island City. He is the The creative forces behind the presentation are actor Yannis founder and director of The Acting Place, an on-going Simonides, director Loukas Skipitaris, costume designer professional acting workshop as well as the founding and Theoni Aldredge, and percussionist Caryn Heilman. Yannis artistic director of Theatron, Inc a non profit Greek American Simonides is a Yale Drama School trained actor/writer and performing arts center in NYC. Emmy-winning documentary producer. He has served as chairman of the NYU Tisch Drama Department and as With over 150 stage productions, numerous ballets and several executive producer of GOTelecom Media. -

Final Honours School

FINAL HONOURS SCHOOL DESCRIPTION OF LITERATURE AND LINGUISTICS PAPERS IN FINALS LINGUISTICS PAPERS (PAPERS IV AND V) Paper IV: History of the Greek Language Topics covered include the major developments in phonology, morphology and syntax in the medieval period and later, dialectal variation and the language debate. Five texts are set for detailed study: Ptochoprodromika III (ed. H. Eideneier), Digenis Akritis, E 1501-1599 (ed. E. Jeffreys) Livistros, vv. 1-229 (ed. T. Lendari) Machairas, § 261-267 (ed. R.M. Dawkins) Erotokritos, I, 1-146 and III, 49-180 (ed. St. Alexiou) Useful for introductory reading is: G. Horrocks, Greek: A History of the Language and its Speakers (London 1997). Paper V: Contemporary Greek Topics covered include an examination of the structure of the Greek language as it is spoken and written today and an analysis of spoken and written Greek in terms of its sound system, inflectional system, verbal aspect, syntax and vocabulary. Useful for introductory reading are: P. Mackridge, The Modern Greek Language (Oxford 1985) R. Hesse, Syntax of the Modern Greek Verbal System (2Copenhagen 2003). PERIOD PAPERS (PAPERS VI, VII AND VIII) Paper VI: Byzantine Greek, AD 324 to 1453 The texts studied in this paper are chosen from those written in the learned form of the language, which corresponds very closely to Ancient Greek. Particular attention will be paid to the middle Byzantine period. Prose authors who will be studied include the historians Theophanes, Psellos, Anna Komnene and Niketas Choniates. Verse by writers such Romanos, George of Pisidia, John Geometres, Christopher Mitylenaios, John Mauropous and Theodore Prodromos will also be read, together with epigrams by a variety of authors from a range of periods. -

2011 Joint Conference

Joint ConferenceConference:: Hellenic Observatory,The British SchoolLondon at School Athens of & Economics & British School at Athens Hellenic Observatory, London School of Economics Changing Conceptions of “Europe” in Modern Greece: Identities, Meanings, and Legitimation 28 & 29 January 2011 British School at Athens, Upper House, entrance from 52 Souedias, 10676, Athens PROGRAMME Friday, 28 th January 2011 9:00 Registration & Coffee 9:30 Welcome : Professor Catherine Morgan , Director, British School at Athens 9:45 Introduction : Imagining ‘Europe’. Professor Kevin Featherstone , LSE 10:15 Session One : Greece and Europe – Progress and Civilisation, 1890s-1920s. Sir Michael Llewellyn-Smith 11:15 Coffee Break 11:30 Session Two : Versions of Europe in the Greek literary imagination (1929- 1961). Professor Roderick Beaton , King’s College London 12:30 Lunch Break 13:30 Session Three : 'Europe', 'Turkey' and Greek self-identity: The antinomies of ‘mutual perceptions'. Professor Stefanos Pesmazoglou , Panteion University Athens 14:30 Coffee Break 14:45 Session Four : The European Union and the Political Economy of the Greek State. Professor Georgios Pagoulatos , Athens University of Economics & Business 15:45 Coffee Break 16:00 Session Five : Contesting Greek Exceptionalism: the political economy of the current crisis. Professor Euclid Tsakalotos , Athens University Of Economics & Business 17:00 Close 19:00 Lecture : British Ambassador’s Residence, 2 Loukianou, 10675, Athens Former Prime Minister Costas Simitis on ‘European challenges in a time of crisis’ with a comment by Professor Kevin Featherstone 20:30 Reception 21:00 Private Dinner: British Ambassador’s Residence, 2 Loukianou, 10675, Athens - By Invitation Only - Saturday, 29 th January 2011 10:00 Session Six : Time and Modernity: Changing Greek Perceptions of Personal Identity in the Context of Europe. -

Transplanting Surrealism in Greece- a Scandal Or Not?

International Journal of Social and Educational Innovation (IJSEIro) Volume 2 / Issue 3/ 2015 Transplanting Surrealism in Greece- a Scandal or Not? NIKA Maklena University of Tirana, Albania E-mail: [email protected] Received 26.01.2015; Accepted 10.02. 2015 Abstract Transplanting the surrealist movement and literature in Greece and feedback from the critics and philological and journalistic circles of the time is of special importance in the history of Modern Greek Literature. The Greek critics and readers who were used to a traditional, patriotic and strictly rule-conforming literature would find it hard to accept such a kind of literature. The modern Greek surrealist writers, in close cooperation mainly with French surrealist writers, would be subject to harsh criticism for their surrealist, absurd, weird and abstract productivity. All this reaction against the transplanting of surrealism in Greece caused the so called “surrealist scandal”, one of the biggest scandals in Greek letters. Keywords: Surrealism, Modern Greek Literature, criticism, surrealist scandal, transplanting, Greek letters 1. Introduction When Andre Breton published the First Surrealist Manifest in 1924, Greece had started to produce the first modern works of its literature. Everything modern arrives late in Greece due to a number of internal factors (poetic collection of Giorgios Seferis “Mythistorima” (1935) is considered as the first modern work in Greek literature according to Αlexandros Argyriou, History of Greek Literature and its perception over years between two World Wars (1918-1940), volume Α, Kastanioti Publications, Athens 2002, pp. 534-535). Yet, on the other hand Greek writers continued to strongly embrace the new modern spirit prevailing all over Europe. -

The Explorations and Poetic Avenues of Nikos Kavvadias

THE EXPLORATIONS AND POETIC AVENUES OF NIKOS KAVVADIAS IAKOVOS MENELAOU * ABSTRACT. This paper analyses some of the influences in Nikos Kavvadias’ (1910-1975) poetry. In particular – and without suggesting that such topic in Kavvadias’ poetry ends here – we will examine the influences of the French poet Charles Baudelaire and the English poet John Mase- field. Kavvadias is perhaps a sui generis case in Modern Greek literature, with a very distinct writing style. Although other Greek poets also wrote about the sea and their experiences during their travelling, Kavvadias’ references and descriptions of exotic ports, exotic women and cor- rupt elements introduce the reader into another world and dimension: the world of the sailor, where the fantasy element not only exists, but excites the reader’s imagination. Although the world which Kavvadias depicts is a mixture of fantasy with reality—and maybe an exaggerated version of the sailor’s life, the adventures which he describes in his poems derive from the ca- pacity of the poetic ego as a sailor and a passionate traveller. Without suggesting that Kavvadias wrote some sort of diary-poetry or that his poetry is clearly biographical, his poems should be seen in connection with his capacity as a sailor, and possibly the different stories he read or heard during his journeys. Kavvadias was familiar with Greek poetry and tradition, nonetheless in this article we focus on influences from non-Greek poets, which together with the descriptions of his distant journeys make Kavvadias’ poems what they are: exotic and fascinating narratives in verse. KEY WORDS: Kavvadias, Baudelaire, Masefield, comparative poetry Introduction From an early age to the end of his life, Kavvadias worked as a sailor, which is precisely why it can be argued that his poetry had been inspired by his numerous travels around the world. -

Alma Mater Studiorum - Università Di Bologna Aristoteleion Panepistimion Thessaloniki Université De Strasbourg

ALMA MATER STUDIORUM - UNIVERSITÀ DI BOLOGNA ARISTOTELEION PANEPISTIMION THESSALONIKI UNIVERSITÉ DE STRASBOURG Master Erasmus Mundus en Cultures Littéraires Européennes - CLE INTITULÉ DU MÉMOIRE Entre poésie et politique : Le cas de Paul Éluard et Manolis Anagnostakis Présenté par Theano Karafoulidou Directeur Tesi di laurea in Prof. Georges Fréris Letteratura comparata Co-directeurs Prof. Patrick Werly Prof. Ruggero Campagnoli Letteratura francese 2011/2012 Je voudrais remercier mon directeur de recherche, M. Georges Fréris, pour ses conseils, ma mère pour son soutien moral et Francisco, sans lequel ce travail n’aurait jamais fini. A la mémoire de ma tante Maria, qui a su résister « Que croyez-vous que soit un artiste? Un imbécile qui n’a que des yeux s’il est peintre, des oreilles s’il est musicien, ou une lyre à tous les étages du cœur s’il est poète, ou même, s’il est boxeur, seulement des muscles ? Bien au contraire, il est en même temps un être politique, constamment en éveil devant les déchirants, ardents ou doux événements du monde, se façonnant de toute pièce à leur image. Comment serait-il possible de se désintéresser des hommes et, en vertu de quelle nonchalance ivoirine, de se détacher d’une vie qu’ils vous apportent si copieusement ? Non, la peinture n’est pas faite pour décorer les appartements. C’est un instrument de guerre offensive et défensive contre l’ennemi. »1 1 Paul Éluard, Anthologie des écrits sur l’art, Éditions Cercle d’Art, 1987, p. 21. PABLO PICASSO Sommaire Introduction.................................................................................................p.6 I. Deux poètes, deux arrière-plans.......................................................p.8 i. -

Cultures of Exile: Conversations on Language and the Arts Eleni Bastéa

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Faculty Publications Architecture and Planning 4-22-2014 Cultures of Exile: Conversations on Language and the Arts Eleni Bastéa Walter Putnam Mark Forte Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/arch_fsp Part of the Landscape Architecture Commons, and the Urban, Community and Regional Planning Commons Recommended Citation Bastéa, Eleni; Walter Putnam; and Mark Forte. "Cultures of Exile: Conversations on Language and the Arts." (2014). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/arch_fsp/1 This Poster is brought to you for free and open access by the Architecture and Planning at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The International Studies Institute presents Cultures of Exile Conversations on Language & the Arts Wings, Hung Liu Co-organizers: Eleni Bastéa and Walter Putnam Conference Program October 23 - 25, 2013 University of New Mexico Albuquerque International Studies Institute International Studies Institute University of New Mexico Eleni Bastéa, Director Christine Sauer, Associate Director MSC03 2165 Humanities, 4th Floor, Room 415A 1 University of New Mexico Albuquerque, NM 87131 Phone: (505) 277-1991 Fax: (505) 277-1208 Jazmin Knight, Operations Specialist [email protected] isi.unm.edu Table of Contents About the Conference. 4 Schedule. 5 Participants . 8 About the International Studies Institute . .30 Sponsors. .31 About the Conference The conference “Cultures of Exile: Conversations on Language and the Arts” was inspired by the music of Georges Moustaki (1934--2013), es- pecially his song “Le Métèque” (1969). In “Le Métèque” Moustaki dealt with outsiders, strangers, and all those who do not share one homoge- neous place of origin. -

2020 Menelaou Iakovos 13556

This electronic thesis or dissertation has been downloaded from the King’s Research Portal at https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/ Reading Cavafy through the medical humanities illness, disease and death Menelaou, Iakovos Awarding institution: King's College London The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without proper acknowledgement. END USER LICENCE AGREEMENT Unless another licence is stated on the immediately following page this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ You are free to copy, distribute and transmit the work Under the following conditions: Attribution: You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Non Commercial: You may not use this work for commercial purposes. No Derivative Works - You may not alter, transform, or build upon this work. Any of these conditions can be waived if you receive permission from the author. Your fair dealings and other rights are in no way affected by the above. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 10. Oct. 2021 1 | P a g e Reading Cavafy through the Medical Humanities: Illness, Disease and Death By Iakovos Menelaou King’s College London, 2019 2 | P a g e Abstract: This thesis seeks to break new ground in Modern Greek studies and the medical humanities. -

A Journal for Greek Letters from Stories to Narratives: the Enigmas of Transition

Vol. 18 2016 - 2017 Introduction a Journal for Greek letters From Stories to Narratives: the enigmas of transition Editors Vrasidas Karalis and Panayota Nazou 1 Vol. 18 2016 - 2017 a Journal for Greek letters From Stories to Narratives: the enigmas of transition Editors Vrasidas Karalis and Panayota Nazou The Modern Greek Studies by academics are refereed (standard process of blind peer Association of Australia and assessment). This is New Zealand (MGSAANZ) a DEST recognised publication. President - Vrasidas Karalis Το περιοδικό φιλοξενεί άρθρα στα Αγγλικά και Vice President - Maria Herodotou τα Ελληνικά αναφερόμενα σε όλες τις απόψεις Treasurer - Panayota Nazou των Νεοελληνικών Σπουδών (στη γενικότητά Secretary - Panayiotis Diamadis τους). Υποψήφιοι συνεργάτες θα πρέπει να The Modern Greek Studies Association of Australia υποβάλλουν κατά προτίμηση τις μελέτες των and New Zealand (MGSAANZ) was founded in 1990 σε ηλεκτρονική και σε έντυπη μορφή. Όλες οι as a professional association by those in Australia συνεργασίες από πανεπιστημιακούς έχουν υπο- and New Zealand engaged in Modern Greek Studies. Membership is open to all interested in any area of βληθεί στην κριτική των εκδοτών και επιλέκτων Greek studies (history, literature, culture, tradition, πανεπιστημιακών συναδέλφων. economy, gender studies, sexualities, linguistics, The editors would like to express their cinema, Diaspora etc.). Published for the Modern Greek Studies Association gratitude to Mr. Nick Valis & Blink Print The Association issues a Newsletter (Ενημέρωση), of Australia -

Author' Graduate Compos of the W Entitled of Moder an MFA Tisch Sc

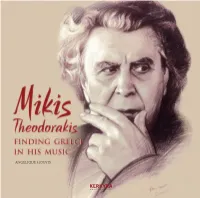

Mikis Theodorakis is a man of many definitions and an inexhaustible supply of talents: poet, musician, composer, MODERN GREEK CULTURE - conductor, political activist, deputy, freedom fighter, exile, partisan, orator and yes, author. Angelique Mouyis’ oeuvre is an important addition to our understanding of his music. And of course, a book about Mikis is also a voyage into modern Greek history and modern Greek culture. Author’s biography ALSO PUBLISHED IN ENGLISH Nick Papandreou, author of Mikis and Manos: A Tale of Two Composers Angelique Mouyis was Coffee Table Books born in Johannesburg, Mikis Theodorakis: My Posters South Africa in 1981 to (bilingual, paperback) Angelique Mouyis has performed a valuable service to the composer and to serious lovers of Greek music by writing about the “other” Theodorakis, a man whose large and impressive body of work in many different Greek-Cypriot parents. In Mikis Theodorakis: My Posters genres deserves better recognition. 2007, under the (bilingual, collector’s edition, supervision of Prof. Jeanne hardcover) Her study is an important contribution to the understanding of Theodorakis’ music, a subject which has MIKIS THEODORAKIS: FINDING GREECE IN HIS MUSIC Zaidel-Rudolph and Prof. Greece Star & Secret Islands been largely neglected by musicologists in his own country, and which deserves to be better known in all its Mary Rörich, she (bilingual) brilliance and abundance by music lovers all over the world. graduated with a Master’s Degree in Music Magical Greece (bilingual, Composition with distinction at the University paperback) Gail Holst-Warhaft, Cornell University of the Witwatersrand, with a research report Magical Greece (bilingual, collector’s edition, hardcover) entitled Mikis Theodorakis and the Articulation A meditation on the perplexity of Greece, the oldest nation but the youngest state, of Modern Greek Identity. -

Modern Greek

UNIVERSITY OF OXFORD FACULTY OF MEDIEVAL AND MODERN LANGUAGES Handbook for the Final Honour School in Modern Greek 2018-19 For students who start their FHS course in October 2018 and normally expect to be taking the FHS examination in Trinity Term 2021 This handbook gives subject-specific information for your FHS course in Modern Greek. For general information about your studies and the faculty, please consult the Faculty’s Undergraduate Course Handbook (https://weblearn.ox.ac.uk/portal/site/:humdiv:modlang). SUB-FACULTY TEACHING STAFF The Sub-Faculty of Byzantine and Modern Greek (the equivalent of a department at other universities) is part of the Faculty of Medieval and Modern Languages and at present is made up of the following holders of permanent posts: Prof. Marc Lauxtermann (Exeter) 66 St Giles, tel. (2)70483 [email protected] Prof. Dimitris Papanikolaou (St Cross) 47 Wellington Square, tel. (2)70482 [email protected] Kostas Skordyles (St Peter’s) 47 Wellington Square, tel. (2)70473 [email protected] In addition, the following Faculty Research Fellows, other Faculty members and Emeriti Professors are also attached to the Sub-Faculty and deliver teaching: Prof. Constanze Guthenke Prof. Elizabeth Jeffreys Prof. Peter Mackridge Prof. Michael Jeffreys Dr Sarah Ekdawi Dr Marjolijne Janssen Ms Maria Margaronis FINAL HONOUR SCHOOL DESCRIPTION OF LANGUAGE PAPERS Paper I: Translation into Greek and Essay This paper consists of a prose translation from English into Modern Greek of approximately 250 words and an essay in Greek of about 500-700 words. -

Modern Greek

UNIVERSITY OF OXFORD FACULTY OF MEDIEVAL AND MODERN LANGUAGES Handbook for the Final Honour School in Modern Greek 2020-21 For students who start their FHS course in October 2020 and expect to be taking the FHS examination in Trinity Term 2024 SUB-FACULTY TEACHING STAFF The Sub-Faculty of Byzantine and Modern Greek (the equivalent of a department at other universities) is part of the Faculty of Medieval and Modern Languages and at present is made up of the following holders of permanent posts: Prof. Marc Lauxtermann (Exeter) 66 St Giles, tel. (2)70483 [email protected] Prof. Dimitris Papanikolaou (St Cross) 47 Wellington Square, tel. (2)70482 [email protected] Dr. Kostas Skordyles (St Peter’s) 47 Wellington Square, tel. (2)70473 [email protected] In addition, the following Faculty Research Fellows, other Faculty members and Emeriti Professors are also attached to the Sub-Faculty and deliver teaching: Prof. Constanze Guthenke Prof. Elizabeth Jeffreys Prof. Peter Mackridge Prof. Michael Jeffreys Dr Sarah Ekdawi Dr Marjolijne Janssen Ms Maria Margaronis 2 FINAL HONOUR SCHOOL DESCRIPTION OF LANGUAGE PAPERS Paper I: Translation into Greek and Essay This paper consists of a prose translation from English into Greek of approximately 250 words and an essay in Greek of about 500-700 words. Classes for this paper will help you to actively use more complex syntactical structures, acquire a richer vocabulary, enhance your command of the written language, and enable you to write clearly and coherently on sophisticated topics. Paper IIA and IIB: Translation from Greek This paper consists of a translation from Greek into English of two texts of about 250 words each.