John Malcolm Montgomery | Caroline Pleasants Mosby

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of Staff Officers of the Confederate States Army. 1861-1865

QJurttell itttiuetsity Hibrary Stliaca, xV'cni tUu-k THE JAMES VERNER SCAIFE COLLECTION CIVIL WAR LITERATURE THE GIFT OF JAMES VERNER SCAIFE CLASS OF 1889 1919 Cornell University Library E545 .U58 List of staff officers of the Confederat 3 1924 030 921 096 olin The original of this book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924030921096 LIST OF STAFF OFFICERS OF THE CONFEDERATE STATES ARMY 1861-1865. WASHINGTON: GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE. 1891. LIST OF STAFF OFFICERS OF THE CONFEDERATE ARMY. Abercrombie, R. S., lieut., A. D. C. to Gen. J. H. Olanton, November 16, 1863. Abercrombie, Wiley, lieut., A. D. C. to Brig. Gen. S. G. French, August 11, 1864. Abernathy, John T., special volunteer commissary in department com- manded by Brig. Gen. G. J. Pillow, November 22, 1861. Abrams, W. D., capt., I. F. T. to Lieut. Gen. Lee, June 11, 1864. Adair, Walter T., surg. 2d Cherokee Begt., staff of Col. Wm. P. Adair. Adams, , lieut., to Gen. Gauo, 1862. Adams, B. C, capt., A. G. S., April 27, 1862; maj., 0. S., staff General Bodes, July, 1863 ; ordered to report to Lieut. Col. R. G. Cole, June 15, 1864. Adams, C, lieut., O. O. to Gen. R. V. Richardson, March, 1864. Adams, Carter, maj., C. S., staff Gen. Bryan Grimes, 1865. Adams, Charles W., col., A. I. G. to Maj. Gen. T. C. Hiudman, Octo- ber 6, 1862, to March 4, 1863. Adams, James M., capt., A. -

![Souvenir, the Seventeenth Indiana Regiment [Electronic Resource]: a History from Its Organization to the End of the War, Giving](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5949/souvenir-the-seventeenth-indiana-regiment-electronic-resource-a-history-from-its-organization-to-the-end-of-the-war-giving-395949.webp)

Souvenir, the Seventeenth Indiana Regiment [Electronic Resource]: a History from Its Organization to the End of the War, Giving

SOUVENIR THE SEVENTEENTH INDIANA REGIMENT. a history from its organization to the end of the war Giving Description of Battles, Etc. also LIST OF THE SURVIVORS; THEIR NAMES; AGES? COMPANY, AND F\ O. ADDRESS. AND INTERESTING LETTERS FROM COMRADES WHO WERE NOT PRESENT AT THE REGIMENTAL REUNIONS PREAMBLE. We are rapidly approaching the fiftieth anniversary of one of the most important battles of the great Civil War of 1861 to 1865. A large majority of its survivors have answered to their last roll call. On September 18 to 20, 1863, was fought the great battle of Ohicka- mauga, in which the Seventeenth Indiana, in connection with Wilder's Lightning Brigade of mounted infantry took an important part. In many respects Chickamauga was the fiercest conflict of all those that took place between the National and Confederate forces. Ere long the last survivor of that great conflict shall have passed away. On that account the author hereof, with the sanction of our beloved com- manders, General J. T. Wilder and others of the Seventeenth Regiment, de- cided to publish this souvenir volume, and he sincerely trusts that his efforts in its composition will be appreciated by the comrades, their families and friends. < At the last meeting of the regimental association, which was held in the city of Anderson, on September 16 and 17, on adjournment it was de- cided, upon request of General Wilder, that our next reunion should be held at the same time and place of the Wilder's Brigade reunion. Since that time the writer hereof has been officially informed that that association, at its meeting at Mattoon, Illinois, decided to hold the next reunion of the brigade at Chattanooga and Chickamauga on September 17 to 20, 1913: hence it is the earnest wish of the author to have the books completed and ready for distribution to the comrades at that time and place. -

Letter to Congressional Leaders Transmitting a Report on Funding for Trade and Development Agency Activities with Respect to China January 13, 2001

Administration of William J. Clinton, 2001 / Jan. 16 its agencies or instrumentalities, officers, em- NOTE: An original was not available for ployees, or any other person, or to require any verification of the content of this memorandum, procedures to determine whether a person is which was not received for publication in the Fed- a refugee. eral Register. You are authorized and directed to publish this memorandum in the Federal Register. WILLIAM J. CLINTON Letter to Congressional Leaders Transmitting a Report on Funding for Trade and Development Agency Activities With Respect to China January 13, 2001 Dear Mr. Speaker: (Dear Mr. President:) Development Agency with respect to the Peo- I hereby transmit a report including my rea- ple’s Republic of China. sons for determining, pursuant to the authority Sincerely, vested in me by section 902 of the Foreign WILLIAM J. CLINTON Relations Authorization Act, Fiscal Years 1990 and 1991 (Public Law 101–246), that it is in NOTE: Identical letters were sent to J. Dennis the national interest of the United States to Hastert, Speaker of the House of Representatives, terminate the suspension on the obligation of and Albert Gore, Jr., President of the Senate. This funds for any new activities of the Trade and letter was released by the Office of the Press Sec- retary on January 16. Remarks on Presenting the Medal of Honor January 16, 2001 The President. Good morning, and please be So when the Medal of Honor was instituted seated. I would like to first thank Chaplain Gen- during the Civil War, it was agreed it would eral Hicks for his invocation and welcome the be given only for gallantry, at the risk of one’s distinguished delegation from the Pentagon who life above and beyond the call of duty. -

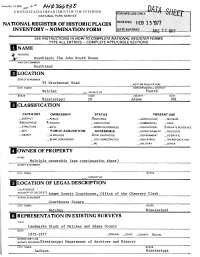

Hclassification

Form No 10-300 ^ \Q-1^ f*H $ *3(0(0 ?3 % UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS NAME HISTORIC Routhland; The John Routh House AND/OR COMMON Routhland 92 Winchester Road —NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Natchez _. VICINITY OF Fourth STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Mississippi 28 Adams 001 HCLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE _ DISTRICT _ PUBLIC -^OCCUPIED —AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM ^BUILDING(S) ?_PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE _BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL 2LPRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _IN PROCESS -XYES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED — YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION _NO —MILITARY —OTHER: [OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Multiple ownership (see continuation sheet) STREET & NUMBER CITY. TOWN STATE VICINITY OF LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEDS,ETC. Adams County Courthouse, Office of the Chancery Clerk STREET & NUMBER Courthouse Square CITY. TOWN STATE Natchez Mississippi REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Landmarks Study of Natchez and Adams County DATE 1972-1977 —FEDERAL _STATE —COUNTY J?LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Mississippi Department of Archives and History CITY, TOWN STATE Jackson Mississippi j DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE .^EXCELLENT _DETERIORATED _UNALTERED X_ORIGINAL SITE _GOOD _RUINS FALTERED _MOVED DATE____ _FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE Routhland is located in the old suburbs lying just southeast of the original town of Natchez. The house occupies the summit of a high but gently-rounded hill in a large landscaped park. -

The Journal of Mississippi History

The Journal of Mississippi History Special Civil War Edition Winter 2013 CONTENTS Introduction 1 By Michael B. Ballard Wrong Job, Wrong Place: John C. Pemberton’s Civil War 3 By Michael B. Ballard The Naval War in Mississippi 11 By Gary D. Joiner Ulysses S. Grant and the Strategy of Camaraderie 21 By John F. Marszalek Newt Knight and the Free State of Jones: Myth, Memory, 27 and Imagination By Victoria E. Bynum “How Does It All Sum Up?”: The Significance of the 37 Iuka-Corinth Campaign By Timothy B. Smith From Brice’s Crossroads to Grierson’s Raid: The Struggle 45 for North Mississippi By Stewart Bennett Unionism in Civil War North Mississippi 57 By Thomas D. Cockrell “Successful in an eminent degree”: Sherman’s 1864 71 Meridian Expedition By Jim Woodrick “The Colored Troops Fought Like Tigers”: Black 81 Mississippians in the Union Army, 1863–1866 By Jeff T. Giambrone A Soldier’s Legacy: William T. Rigby and the Establishment 93 of Vicksburg National Military Park By Terrence J. Winschel Contributors 111 COVER IMAGE—Mississippi Monument, Vicksburg National Military Park. Courtesy of the Mississippi Department of Archives and History. The Journal of Mississippi History (ISSN 0022-2771) is published quarterly by the Mis- sissippi Department of Archives and History, 200 North State St., Jackson, MS 39201, in cooperation with the Mississippi Historical Society as a benefit of Mississippi Historical Society membership. Annual memberships begin at $25. Back issues of the Journal sell for $7.50 and up through the Mississippi History Store; call 601-576-6921 to check avail- ability. -

James (Jim) B. Simms

February 2013 1 I Salute The Confederate Flag; With Affection, Reverence, And Undying Devotion To The Cause For Which It Stands. From The Adjutant The General Robert E. Rodes Camp 262, Sons of Confederate Veterans, will meet on Thursday night, January 10, 2013. The meeting starts at 7 PM in the Tuscaloosa Public Library Rotary Room, 2nd Floor. The Library is located at 1801 Jack Warner Parkway. The program for February will be DVD’s on General Rodes and one of his battles. The Index of Articles and the listing of Camp Officers are now on Page Two. Look for “Sons of Confederate Veterans Camp #262 Tuscaloosa, AL” on our Facebook page, and “Like” us. James (Jim) B. Simms The Sons of Confederate Veterans is the direct heir of the United Confederate Veterans, and is the oldest hereditary organization for male descendants of Confederate soldiers. Organized at Richmond, Virginia in 1896; the SCV continues to serve as a historical, patriotic, and non-political organization dedicated to ensuring that a true history of the 1861-1865 period is preserved. Membership is open to all male descendants of any veteran who served honorably in the Confederate military. Upcoming 2013 Events 14 February - Camp Meeting 13 June - Camp Meeting 14 March - Camp Meeting 11 July - Camp Meeting 11 April - Camp Meeting August—No Meeting 22-26 - TBD - Confederate Memorial Day Ceremony Annual Summer Stand Down/Bivouac 9 May - Camp Meeting 12 September - Camp Meeting 2 Officers of the Rodes Camp Commander David Allen [email protected] 1st Lieutenant John Harris Commander -

The Battles of Mansfield (Sabine Crossroads) and Pleasant Hill, Louisiana, 8 and 9 April 1864

RICE UNIVERSITY DEAD-END AT THE CROSSROADS: THE BATTLES OF MANSFIELD (SABINE CROSSROADS) AND PLEASANT HILL, LOUISIANA, 8 AND 9 APRIL 1864 by Richard Leslie Riper, Jr. A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS Thesis Director's Signature Houston, Texas May, 1976 Abstract Dead-End at the Crossroads: The Battles of Mansfield (Sabine Cross¬ roads) and Pleasant Hill, Louisiana, 8 and 9 April 1864 Richard Leslie Riper, Jr. On 8 April 1864 a Union army commanded by Major General Nathaniel P. Banks was defeated by a Confederate army commanded by Major General Richard Taylor at the small town of Mansfield, Louisiana. In Union records the engagement was recorded as the battle of Sabine Crossroads, and the defeat signaled the "high-water mark" for the Union advance toward Shreveport. General Banks, after repeated urging by Major General Henry Hal- leck, General-in-Chief of the Union Army, had launched a drive up the Red River through Alexandria and Natchitoches to capture Shreveport, the industrial hub of the Trans-Mississippi Department. From New Or¬ leans and Berwick, Louisiana, and from Vicksburg, Mississippi, the Fédérais converged on Alexandria. From Little Rock, Arkansas, a Union column under Major General Frederick Steele was to join Banks at Shreve¬ port. Three major infantry forces and the Union Navy under Admiral David D. Porter were to participate in the campaign, yet no one was given supreme authority to coordinate the forces. Halleck's orders were for the separate commands only to co-operate with Banks--a clear viola¬ tion of the principle of unity of command. -

Bowling Green Civil War Round Table Newsletter History

Western Kentucky University TopSCHOLAR® Bowling Green Civil War Round Table Newsletter History 3-2015 Bowling Green Civil War Round Table Newsletter (March 2015 Manuscripts & Folklife Archives Western Kentucky University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wku.edu/civil_war Part of the Military History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Folklife Archives, Manuscripts &, "Bowling Green Civil War Round Table Newsletter (March 2015" (2015). Bowling Green Civil War Round Table Newsletter. Paper 20. https://digitalcommons.wku.edu/civil_war/20 This Newsletter is brought to you for free and open access by TopSCHOLAR®. It has been accepted for inclusion in Bowling Green Civil War Round Table Newsletter by an authorized administrator of TopSCHOLAR®. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 Founded March 2011 – Bowling Green, Kentucky President –Tom Carr; Vice President - Jonathan Jeffrey; Secretary – Carol Crowe-Carraco; Treasurer – Robert Dietle; Advisors – Glenn LaFantasie and - Greg Biggs (Program Chair and President-Clarksville CWRT) The Bowling Green KY Civil War Round Table meets on the 3rd Thursday of each month (except June, July, and December). Email: [email protected] Rm. 125, Cherry Hall, on the Campus of Western Kentucky University. The meeting begins at 7:00 pm and is always open to the public. Members please bring a friend or two – new recruits are always welcomed Our Program for March 19th, 2015 Mark Hoffman, - "The First Michigan Engineers and Mechanics" Bio: Mark Hoffman currently serves as the Chief Administrative Officer for the Michigan Department of Natural Resources. Previous to the DNR, Hoffman was deputy director of the Michigan Department of History, Arts and Libraries and also on the staff of the Michigan Bureau of State Lottery and the Michigan House of Representatives. -

Jacob Nicholls Clark - Revolutionary War Soldier by Wilma J

Jacob Nicholls Clark - Revolutionary War Soldier By Wilma J. Clark of Deltona, Florida Jacob Nicholls Clark, born 13 October 1754, followed his brother James Clark into military service in the Revolutionary War in January of 1776. James had enlisted from Baltimore, Maryland in 1775. Jacob enlisted under Captain Samuel Smith in the First Regiment of the Maryland Line, in Baltimore Maryland, which was commanded by Colonel William Smallwood.1 Jacob’s Regiment marched from Baltimore, through Pennsylvania and New Jersey to the American Army Headquarters in New York City. 27 August 1776 he fought in the Battle of Long Island, which was commanded by Lord Sterling, and then retreated with the troops to Fort Washington, York Island, New York. The British and Hessians attacked Fort Washington 16 November 1776, overpowering the American Army, and forcing a surrender of Fort Washington to the Hessians. Jacob and other surviving American soldiers fled across the Hudson River to Fort Lee, New Jersey, only to find that Fort Lee had also been captured 20 November 1776. After these defeats, the Continental Army was exhausted, demoralized and uncertain of its future. It was a cold winter and many of the soldiers were now walking barefoot in the snow, leaving trails of blood. Believing that the need to raise the hopes and spirits of the troops and people was imperative, General George Washington, Commander in Chief, ordered a massive surprise attack on the Hessian held city of Trenton, New Jersey. Colonel Smallwood’s First Maryland Regiment marched into the Battle of Trenton under the command of Major General Nathaniel Greene, 26 December 1776,2 and Jacob was once again engaged in battle. -

The Civil War

AND THE CIVIL WAR PENNSYLVANIA CIVIL WAR TRAILS AND AMERICAN HERITAGE ANNOUNCING PENNSYLVANIA'S SALUTE TO THE USCT GRAND REVIEW ME MORY AND COmmEMORATION During the Civil War, Pennsylvania armies that took place in Washington, D.C. proved to be a vital keystone for pre- The African American citizens of Harrisburg made up for that serving the Union. The very first Union egregious affront by organizing their own review of the United volunteers to arrive in Washington to States Colored Troops in the Pennsylvania capital on November defend the nation’s capital came from 14, 1865. It was well-deserved recognition for the service and Pennsylvania, thanks to the efforts of sacrifice of these valiant troops. Gov. Andrew Gregg Curtin. Nearly 150 years later, it remains important that we remember However, some men were not allowed both these men and the twin causes for which they fought: for to fight for their country simply because their country, and for their own status as citizens and free men. of the color of their skin. When black men The events in Harrisburg and throughout Pennsylvania will help were finally allowed to enlist toward the us bring these soldiers out from history’s shadows and honor end of the war, they quickly made up for having been excluded: their willingness to dedicate “the last full measure of devotion” nearly 200,000 black soldiers eventually joined the Union cause. on a journey that led from Civil War to Civil Rights. Yet, after the war ended, these brave men were unfairly denied Sincerely, the opportunity to march in the Grand Review of the Union Edward G. -

To Mississippi, Alone, Can They Look for Assistance:” Confederate Welfare in Mississippi

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Aquila Digital Community The University of Southern Mississippi The Aquila Digital Community Master's Theses Summer 8-2017 "To Mississippi, Alone, Can They Look For Assistance:” Confederate Welfare In Mississippi Lisa Carol Foster University of Southern Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/masters_theses Recommended Citation Foster, Lisa Carol, ""To Mississippi, Alone, Can They Look For Assistance:” Confederate Welfare In Mississippi" (2017). Master's Theses. 310. https://aquila.usm.edu/masters_theses/310 This Masters Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “TO MISSISSIPPI, ALONE, CAN THEY LOOK FOR ASSISTANCE:” CONFEDERATE WELFARE IN MISSISSIPPI by Lisa Carol Foster A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate School, the College of Arts and Letters, and the Department of History at The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts August 2017 “TO MISSISSIPPI, ALONE, CAN THEY LOOK FOR ASSISTANCE:” CONFEDERATE WELFARE IN MISSISSIPPI by Lisa Carol Foster August 2017 Approved by: _________________________________________ Dr. Susannah Ural, Committee Chair Professor, History _________________________________________ Dr. Chester Morgan, Committee -

The Civil War Diary of Hoosier Samuel P

1 “LIKE CROSSING HELL ON A ROTTEN RAIL—DANGEROUS”: THE CIVIL WAR DIARY OF HOOSIER SAMUEL P. HERRINGTON Edited by Ralph D. Gray Bloomington 2014 2 Sergeant Samuel P. Herrington Indianapolis Star, April 7, 1912 3 CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION 5 CHAPTERS 1. Off to Missouri (August-December 1861) 17 "There was no one rejected." 2. The Pea Ridge Campaign (January-March 15, 1862) 61 "Lord but how we made things hum." 3. Missouri Interlude (March 16-June 1862) 87 "There is a great many sick [and] wounded." 4. Moving Along the Mississippi (July-December 1862) 111 "We will never have so much fun if we stay ten years in the service." 5. The Approach to Vicksburg (January-May 18, 1863) 149 "We have quite an army here." 6. Vicksburg and Jackson (May 19-July 26, 1863) 177 ". they are almost Starved and cant hold out much longer." 7. To Texas, via Indiana and Louisiana (July 27-December 1863) 201 "The sand blows very badly & everything we eat is full of sand." 8. Guard Duty along the Gulf (January-May 28, 1864 241 "A poor soldier obeys orders that is all." 9. To the Shenandoah and Home (May 29-September 1864) 277 "I was at the old John Brown Fortress where he made his stand for Liberty and Justice." 4 The picture can't be displayed. 5 INTRODUCTION Indiana played a significant role in the Civil War. Its contributions of men and material, surpassed by no other northern state on a percentage basis, were of enormous importance in the total war effort.