Revisiting Irish Ceol Traditions: Samantha Raftery

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1St Annual Dreams Come True Feis Hosted by Central Florida Irish Dance Sunday August 8Th, 2021

1st Annual Dreams Come True Feis Hosted by Central Florida Irish Dance Sunday August 8th, 2021 Musician – Sean Warren, Florida. Adjudicator’s – Maura McGowan ADCRG, Belfast Arlene McLaughlin Allen ADCRG - Scotland Hosted by - Sarah Costello TCRG and Central Florida Irish Dance Embassy Suites Orlando - Lake Buena Vista South $119.00 plus tax Call - 407-597-4000 Registered with An Chomhdhail Na Muinteoiri Le Rinci Gaelacha Cuideachta Faoi Theorainn Rathaiochta (An Chomhdhail) www.irishdancingorg.com Charity Treble Reel for Orange County Animal Services A progressive animal-welfare focused organization that enforces the Orange County Code to protect both citizens and animals. Entry Fees: Pre Bun Grad A, Bun Grad A, B, C, $10.00 per competition Pre-Open & Open Solo Rounds $10.00 per competition Traditional Set & Treble Reel Specials $15.00 per competition Cup Award Solo Dances $15.00 per competition Open Championships $55.00 (2 solos are included in your entry) Championship change fee - $10 Facility Fee $30 per family Feisweb Fee $6 Open Platform Fee $20 Late Fee $30 The maximum fee per family is $225 plus facility fee and any applicable late, change or other fees. There will be no refund of any entry fees for any reason. Submit all entries online at https://FeisWeb.com Competitors Cards are available on FeisWeb. All registrations must be paid via PayPal Competitors are highly encouraged to print their own number prior to attending to avoid congestion at the registration table due to COVID. For those who cannot, competitor cards may be picked up at the venue. For questions contact us at our email: [email protected] or Sarah Costello TCRG on 321-200-3598 Special Needs: 1 step, any dance. -

Bowing Styles in Irish Fiddle Playing Vol 3

Bowing Styles in Irish Fiddle Playing Vol 3 David H. Lyth July 2016 2 This is the third volume of a series of transcriptions of Irish traditional fiddle playing. The others are `Bowing Styles in Irish Fiddle Playing Vol I' and `Bowing Styles in Irish Fiddle Playing Vol 2'. Volume 1 contains reels and hornpipes recorded by Michael Coleman, James Morrison and Paddy Killoran in the 1920's and 30's. Volume 2 contains several types of tune, recorded by players from Clare, Limerick and Kerry in the 1950's and 60's. Volumes I and II were both published by Comhaltas Ceoltoiri Eirann. This third volume returns to the players in Volume 1, with more tune types. In all three volumes, the transcriptions give the bowing used by the per- former. I have determined the bowing by slowing down the recording to the point where the gaps caused by the changes in bow direction can be clearly heard. On the few occasions when a gap separates two passages with the bow in the same direction, I have usually been able to find that out by demanding consistency; if a passage is repeated with the same gaps between notes, I assume that the directions of the bow are also repeated. That approach gives a reliable result for the tunes in these volumes. (For some other tunes it doesn't, and I have not included them.) The ornaments are also given, using the standard notation which is explained in Volumes 1 and 2. The tunes come with metronome settings, corresponding to the speed of the performance that I have. -

Bizourka and Freestyle Flemish Mazurka

118 Bizourka and Freestyle Flemish Mazurka (Flanders, Belgium, Northern France) These are easy-going Flemish mazurka (also spelled mazourka) variations which Richard learned while attending a Carnaval ball near Dunkerque, northern France, in 2009. Participants at the ball were mostly locals, but also included dancers from Belgium and various parts of France. Older Flemish mazurka is usually comprised of combina- tions of the Mazurka Step and Waltz, in various simple patterns (see Freestyle Flemish Mazurka below). Like most folk mazurkas, their style descended from the Polka Mazurka once done in European ballrooms, over 150 years ago. This folk process is sometimes compared to a bridge. French or English dance masters picked up an ethnic dance step, in this case a mazurka step from the Polish Mazur, and standardized it for ballroom use. It was then spread throughout the world by itinerant dance teachers, visiting social dancers, and thousands of easily available dance manuals. From this propagation, the most popular steps (the Polka Mazurka was indeed one of the favorites) then “sank” through many simplified forms in villages throughout Europe, the Americas, Australia and elsewhere. In other words, towns in rural France or England didn’t get their mazurka step directly from Poland, or their polka directly from Bohemia, but rather through the “bridge” of dance teachers, traveling social dancers and books, that spread the ballroom versions of the original ethnic steps throughout the world. Once the steps left the formal setting of the ballroom, they quickly simplified. Then folk dances evolve. Typically steps and styles are borrowed from other dance forms that the dancers also happen to know, adding a twist to a traditional form. -

The Haybaler's

The Haybaler’s Jig An 11 x 32 bar jig for 4 couples in a square. Composed 4 June 2013 by Stanford Ceili. Mixer variant of Haymaker’s Jig. (24) Ring Into The Center, Pass Through, Set. (4) Ring Into The Center. (4) Pass through (pass opposite by Right shoulders).1 (4) Set twice. (12) Repeat.2 (32) Corners Dance. (4) 1st corners turn by Right elbow. (4) 2nd corners repeat. (4) 1st corners turn by Left elbow. (4) 2nd corners repeat. (8) 1st corners swing (“long swing”). (8) 2nd corners repeat. (16) Reel The Set. Note: dancers always turn people of the opposite gender in this figure. (4) #1 couple turn once and a half by Right elbow. (2) Turn top side-couple dancers by Left elbow once around. (2) Turn partner in center by Right elbow once and a half. (2) Repeat with next side-couple dancer. (2) Repeat with partner. (2) Repeat with #2 couple dancer. (2) Repeat with partner. (2) #1 Couple To The Top. 1Based on the “Drawers” figure from the Russian Mazurka Quadrille. All pass their opposites by Right shoulder to opposite’s position. Ladies dance quickly at first, to pass their corners; then men dance quickly, to pass their contra-corners. 2Pass again by Right shoulders, with ladies passing the first man and then allowing the second man to pass her. This time, ladies pass their contra-corners, and are passed by their corners. (14) Cast Off, Arch, Turn. (12) Cast off and arch. #1 couple casts off at the top, each on own side. -

Chopin and Poland Cory Mckay Departments of Music and Computer Science University of Guelph Guelph, Ontario, Canada, N1G 2W 1

Chopin and Poland Cory McKay Departments of Music and Computer Science University of Guelph Guelph, Ontario, Canada, N1G 2W 1 The nineteenth century was a time when he had a Polish mother and was raised in people were looking for something new and Poland, his father was French. Finally, there exciting in the arts. The Romantics valued is no doubt that Chopin was trained exten- the exotic and many artists, writers and sively in the conventional musical styles of composers created works that conjured im- western Europe while growing up in Poland. ages of distant places, in terms of both time It is thus understandable that at first glance and location. Nationalist movements were some would see the Polish influence on rising up all over Europe, leading to an em- Chopin's music as trivial. Indeed, there cer- phasis on distinctive cultural styles in music tainly are compositions of his which show rather than an international homogeneity. very little Polish influence. However, upon Fryderyk Franciszek Chopin used this op- further investigation, it becomes clear that portunity to go beyond the conventions of the music that he heard in Poland while his time and introduce music that had the growing up did indeed have a persistent and unique character of his native Poland to the pervasive influence on a large proportion of ears of western Europe. Chopin wrote music his music. with a distinctly Polish flare that was influ- The Polish influence is most obviously ential in the Polish nationalist movement. seen in Chopin's polonaises and mazurkas, Before proceeding to discuss the politi- both of which are traditional Polish dance cal aspect of Chopin's work, it is first neces- forms. -

A/L CHOPIN's MAZURKA

17, ~A/l CHOPIN'S MAZURKA: A LECTURE RECITAL, TOGETHER WITH THREE RECITALS OF SELECTED WORKS OF J. S. BACH--F. BUSONI, D. SCARLATTI, W. A. MOZART, L. V. BEETHOVEN, F. SCHUBERT, F. CHOPIN, M. RAVEL AND K. SZYMANOWSKI DISSERTATION Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial. Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS By Jan Bogdan Drath Denton, Texas August, 1969 (Z Jan Bogdan Drath 1970 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION . I PERFORMANCE PROGRAMS First Recital . , , . ., * * 4 Second Recital. 8 Solo and Chamber Music Recital. 11 Lecture-Recital: "Chopin's Mazurka" . 14 List of Illustrations Text of the Lecture Bibliography TAPED RECORDINGS OF PERFORMANCES . Enclosed iii INTRODUCTION This dissertation consists of four programs: one lec- ture-recital, two recitals for piano solo, and one (the Schubert program) in combination with other instruments. The repertoire of the complete series of concerts was chosen with the intention of demonstrating the ability of the per- former to project music of various types and composed in different periods. The first program featured two complete sets of Concert Etudes, showing how a nineteenth-century composer (Chopin) and a twentieth-century composer (Szymanowski) solved the problem of assimilating typical pianistic patterns of their respective eras in short musical forms, These selections are preceded on the program by a group of compositions, consis- ting of a. a Chaconne for violin solo by J. S. Bach, an eighteenth-century composer, as. transcribed for piano by a twentieth-century composer, who recreated this piece, using all the possibilities of modern piano technique, b. -

Scottish and Irish Elements of Appalachian Fiddle Music

Butler University Digital Commons @ Butler University Undergraduate Honors Thesis Collection Undergraduate Scholarship 3-1995 Scottish and Irish Elements of Appalachian Fiddle Music Matthew S. Emmick Butler University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/ugtheses Part of the Ethnomusicology Commons, and the Musicology Commons Recommended Citation Emmick, Matthew S., "Scottish and Irish Elements of Appalachian Fiddle Music" (1995). Undergraduate Honors Thesis Collection. 21. https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/ugtheses/21 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Undergraduate Scholarship at Digital Commons @ Butler University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Thesis Collection by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Butler University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BUTLER UNIVERSITY HONORS PROGRAM Honors Thesis Certification Matthew S. Emmick Applicant (Name as It Is to appear on dtplomo) Scottish and Irish Elements of Appalachian Fiddle M'-Isic Thesis title _ May, 1995 lnter'lded date of commencemenf _ Read and approved by: ' -4~, <~ /~.~~ Thesis adviser(s)/ /,J _ 3-,;13- [.> Date / / - ( /'--/----- --",,-..- Commltte~ ;'h~"'h=j.R C~.16b Honors t-,\- t'- ~/ Flrst~ ~ Date Second Reader Date Accepied and certified: JU).adr/tJ, _ 2111c<vt) Director DiJe For Honors Program use: Level of Honors conferred: University Magna Cum Laude Departmental Honors in Music and High Honors in Spanish Scottish and Irish Elements of Appalachian Fiddle Music A Thesis Presented to the Departmt!nt of Music Jordan College of Fine Arts and The Committee on Honors Butler University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Graduation Honors Matthew S. Emmick March, 24, 1995 -l _ -- -"-".,---. -

2020 Syllabus

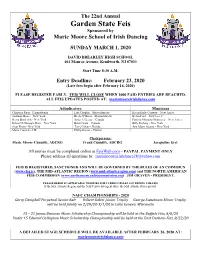

The 22nd Annual Garden State Feis Sponsored by Marie Moore School of Irish Dancing SUNDAY MARCH 1, 2020 DAVID BREARLEY HIGH SCHOOL 401 Monroe Avenue, Kenilworth, NJ 07033 Start Time 8:30 A.M. Entry Deadline: February 23, 2020 (Late fees begin after February 16, 2020) PLEASE REGISTER EARLY. FEIS WILL CLOSE WHEN 1000 PAID ENTRIES ARE REACHED. ALL FEIS UPDATES POSTED AT: mariemooreirishdance.com Adjudicators Musicians Christina Ryan - Pennsylvania Lisa Chaplin – Massachusetts Karen Early-Conway – New Jersey Siobhan Moore - New York Breda O’Brien – Massachusetts Kevin Ford – New Jersey Kerry Broderick - New York Jackie O’Leary – Canada Patricia Moriarty-Morrissey – New Jersey Eileen McDonagh-Morr – New York Brian Grant – Canada Billy Furlong - New York Sean Flynn - New York Terry Gillan – Florida Ann Marie Acosta – New York Marie Connell – UK Philip Owens – Florida Chairpersons: Marie Moore-Cunniffe, ADCRG Frank Cunniffe, ADCRG Jacqueline Erel All entries must be completed online at FeisWeb.com – PAYPAL PAYMENT ONLY Please address all questions to: [email protected] FEIS IS REGISTERED, SANCTIONED AND WILL BE GOVERNED BY THE RULES OF AN COIMISIUN (www.clrg.ie), THE MID-ATLANTIC REGION (www.mid-atlanticregion.com) and THE NORTH AMERICAN FEIS COMMISSION (www.northamericanfeiscommission.org) JIM GRAVEN - PRESIDENT. PLEASE REFER TO APPLICABLE WEBSITES FOR CURRENT RULES GOVERNING THE FEIS If the Mid-Atlantic Region and the NAFC have divergent rules, the Mid-Atlantic Rules prevail. NAFC CHAMPIONSHIPS - 2020 Gerry Campbell Perpetual -

North American Open Championships 2020

Venue: InterContinental Minneapolis-St Paul Airport, 5005 Glumack Drive Minneapolis, MN 55425 Adjudicators: Mr Brian Cleary. ADCRN Ms Lisa Doogan. ADCRN Ms Marian Kiernan. ADCRN Musician: Mr. Sean Warren Competition Entry Fees Solos $15/dance Award Competitions $25 Figure Entries (2-hand, 3-hand, 4- $12/dancer hand, céilí, figure dance, freestyle, and dance drama) Solo Championships $35 Award Competition Without Solos $40 Solo Championships Without Solos $60 Open platform dancers must add a $15 registration fee.* 1 General Admission Age Per Day 3-Day Pass Adult $15 $40 Child (under 12) $5 $25 Senior (65 and $10 $25 older) *Dancers without a CRN lanyard must pay a $5/day entry fee. Closing Date: All entries and payment in full must be transmitted or postmarked by January 15th, 2020. For dancers participating in qualifying events after the entry closing date, entries for award competitions may be added to their solo entries within 6 days after the qualifying event and must be accompanied by payment in full. No other late entries will be accepted. • USA Only: Make checks payable to CRN NAO. Mail to: Jennifer Darby 116 Carson Avenue Dalton, MA 01226 • Returned checks are subject to a $30 fee. • Alternatively, anyone may submit payment (plus 3% of total payment to cover processing fees) via PayPal to [email protected]. • Mail one check or make one PayPal payment per school for the grand total. • All fees are stated in US dollars. • No refunds will be issued. Submit Entries to: Ann English [email protected] 2 Solo Dance Competitions Speeds are noted in beats per minute (bpm). -

(AIDA Inc.) GRADE RULES

AUSTRALIAN IRISH DANCING ASSOCIATION INC. (AIDA Inc.) GRADE RULES VERSION 7 DATED 23rd February 2020 CONTENTS Speeds………………………………………………………………………….………………. Page 2 Grade Rule and Content of Work …………………………………………………… Pages 3 to 6 Method of Upgrade……………………………………………………………………….. Page 7 Addendum A: Rules………………………………………………………………………. Page 8 AIDA Inc. - Grade Rules - Version 7 - 23 February 2020 Page 1 SPEEDS Moved at Convention November 11th and 12th 2006 That the CLRG traditional set speeds be adopted for all feiseanna in Australia from 1st January 2007. DANCES SPEED ST PATRICK'S DAY 94 BLACKBIRD 144 JOB OF JOURNEY WORK 138 GARDEN OF DAISIES 138 KING OF THE FAIRIES 130 JOCKEY TO THE FAIR 90 THREE SEA CAPTAINS 96 Moved at Convention November 14th and 15th November 2009 Beginner and Novice reel speed be 122, Beginner Treble Jig 92 Primary Treble Jig 92 or 82 Primary Hornpipe 144 or 130 AIDA Inc. - Grade Rules - Version 7 - 23 February 2020 Page 2 GRADE RULES NOVICE This grade is a pre-cursor to Beginner (Bun) Grade. It is only available to a dancer in their first open feis (i.e. not a class feis) for each particular dance. DANCES SPEED LENGTH REEL 122 48 LIGHT JIG 116 48 SINGLE JIG 124 48 SLIP JIG 124 40 BEGINNERS (BUN) DANCES SPEED LENGTH REEL 122 48 LIGHT JIG 116 48 SINGLE JIG 124 48 SLIP JIG 124 40 TREBLE JIG 92 32 HORNPIPE 144 32 CONTENT OF WORK – NOVICE AND BEGINNER (BUN) GRADE Basic Work e.g.: 2,3s, sevens, heels, points, skips, knocks, basic trebles. Beginners Reel, Light Jig, Single Jig, slip Jig, Treble Jig to consist of a circle and side and steps up to required length of dance. -

Davy Spillane Pipedreams Mp3, Flac, Wma

Davy Spillane Pipedreams mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Folk, World, & Country Album: Pipedreams Country: Canada Style: Celtic MP3 version RAR size: 1383 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1118 mb WMA version RAR size: 1688 mb Rating: 4.2 Votes: 270 Other Formats: APE AHX MMF DTS ADX RA FLAC Tracklist Hide Credits Shifting Sands 1 4:48 Written-By – A. Drennan*, D. Spillane* Undertow 2 3:14 Written-By – D. Spillane* Shorelines 3 5:00 Written-By – A. Drennan*, D. Spillane* Call Across The Canyon 4 4:44 Written-By – D. Spillane*, L. McCormick*, T. Boland* Midnight Walker 5 4:45 Written-By – D. Spillane* Mistral 6 5:00 Written-By – A. Drennan*, D. Spillane* Rainmaker 7 4:40 Written-By – D. Spillane* Stepping In Silence 8 3:30 Written-By – D. Spillane* Morning Wings 9 4:22 Written-By – D. Spillane* Corcomroe 10 3:53 Written-By – D. Spillane* Companies, etc. Phonographic Copyright (p) – Tara Records Ltd. Copyright (c) – Tara Records Ltd. Copyright (c) – Tara Music Company Ltd. Published By – Sony Music Publishing Published By – Sony Music Published By – Copyright Control Credits Arranged By [Additional] – James Delaney (tracks: 2, 9), Paul Moran (tracks: 2, 9), Tony Molloy (tracks: 2, 9) Bagpipes [Uilleann], Low Whistle – Davy Spillane Bass Guitar – Joe Marcus (tracks: 4), Tony Molloy Bodhrán, Percussion – Tommy Hayes Didgeridoo, Horn [Dord Árd] – Simon O'Dwyer (tracks: 4) Drums, Cymbal, Percussion – Paul Moran Electric Guitar, Acoustic Guitar, Keyboards [Additional] – Anthony Drennan Electric Guitar, Percussion – Tim Boland (tracks: -

2Ltuabus °E . .J2rl~E Com'qec1cions·

[ Q MAY .3rd to 8th, 1928. 2ltUAbus °E_. _ .J2Rl~e COm'QeC1CIOnS· 8.. 7', White, Printer, 4S Fleet Street, Dul·/:"u. " ( Notice to Competitors. OMPETITORS are requested to be careful that in the Feil Ceoil C Competitions, both Instrumental and Vocal, the specified edition is procured. Arrangements have been made by Mesers. Pigott &. Co., Ltd., THI~TIETH "3 Grafton Street, Dublin, to supply Candidates with the Test Piec~s in the correct editions at the lowe.t possible rates. F EIS C EO I L IRISH MUSICAL FESTIVAL. DUBLIN. MAY 3rd to 8th. 1926. SYLLABUS OF PRIZE COMPETITION S AND REPQRT OF MUSIC EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE. AND ALL THINOS MUSICAL. PIANOS ORGANS PLAYER - PIANOS GRAMOPHONES RECORDS VIOLINS Oreatest Facilities for Selection In Ireland. Service. of Expert Tuner. covera entire Country. Repair. by highly Skilled Craftsmen in the Firm'. Up-to-date Factory. DUBLIN : PUBLISHED BY THE FEIS CEOIL AS SOCIATION. 37 MOLESWORTH ST. 1926. GRAFTON ST. a SUFFOLK ST., DUBLIN. L ADd at CORK .. LIMUIC•• R. T. J-f/'lIite, Printer, 45 Fleet Street, Dtlblin, CONTENTS. ................................................ PAGE. 13 Adjudicators, List of. (1926) 6 It is earne.stiy ~equested that Competitions, Con~ltlons of . NOTICE. Constitution of Fels Ceoll 5 all Competitors should use Committees ... ... ... .. 4 Donors to Prize Fund (1925) ... .., 11 the correct and specified editions as stated Members of Association, List of (1925-26) 41 43 in Syllabus. •• •• :: .• Prize Winners, Calendar of .. Railway Travelling Facilities ... .. 11 Above are obtainable at Messrs. Report of Committee and Balance Sheets for 1925 34-40 McCullough's, 56 Dawson Street, Dublin. TEST PIECES AND PRIZES.