The Evolution of Cake and Its Identity in America

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Barefoot (Contessa) in the Kitchen Rachel E

Teaching Media Quarterly Volume 2 | Issue 2 Article 6 2014 Barefoot (Contessa) in the Kitchen Rachel E. Silverman Embry Riddle Aeronautical University, [email protected] David F. Purnell University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://pubs.lib.umn.edu/tmq Recommended Citation Silverman, Rachel E., and David F. Purnell. "Barefoot (Contessa) in the Kitchen." Teaching Media Quarterly 2, no. 2 (2014). http://pubs.lib.umn.edu/tmq/vol2/iss2/6 Teaching Media Quarterly is published by the University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing. Silverman and Purnell: Barefoot (Contessa) in the Kitchen Teaching Media Quarterly Volume 2, Edition 2 (Winter 2014): Teaching about Food and Media Barefoot (Contessa) in the Kitchen Overview and Rationale It is well known that popular culture represents and perpetuates the gender inequities that exist in our culture. Food media are no exception (Swenson, 2013). In fact, food media use gendered cultural norms to sell audiences their products (the shows, the cookbooks, the advertisements during the shows, etc.). In other words, food media commodify gender by selling audiences what they already understand to be true about gender as a way to increase profit (Forbes, 2013). Food media, and food television in particular, offer sites to examine the cultural struggles of gender. Both food and gender are intensely personal, social, and culturally specific phenomena (Barthes, 2013/1961). Further, television shapes the way we understand culture (Fiske, 2010). According to Cramer (2011): As a manifestation of culture, food is one of the most potent media for conveying meanings related to identity, ethnicity, nationhood, gender, class, sexuality and religion – in short, all those aspects of social, political and relational life that convey who and what we are and what matters to us. -

Coconut Cake, Crunchy Texas Toasted Pecan Cake, and Rich Fruitcake

GD01e01.qxp 8/13/2008 3:33 PM Page 13 CAKES GD01e01.qxp 8/13/2008 3:33 PM Page 15 Cakes are the ultimate Southern dessert. The elegant cre- ations are especially in evidence at Thanksgiving and Christmas when tables groan beneath platters of delicate Coconut Cake, crunchy Texas Toasted Pecan Cake, and rich Fruitcake. Cakes are important to other celebrations such as Mardi Gras when the colorful Kings’ Cake plays an essential role in the festivities. The yeasty, ring-shaped dessert is deco- rated with sugar crystals tinted with brilliant carnival colors: purple, green, and gold. Traditionally, a bean or pecan half is tucked inside, and the finder is named king of the next party. Cakes appear frequently throughout Southern history. George Washington’s mother, Mary Ball Washington, was among our first cake-makers. She served fresh-baked ginger- bread, accompanied by a glass of Madeira, to General Lafayette when he visited her at Fredericksburg. Showy Lord and Lady Baltimore Cakes are thought to have been named for the third Lord Baltimore and his Lady, who arrived in 1661 from England to govern the land which later became Maryland. Writer Owen Wister became so enamored with the taste of Lady Baltimore Cake that he named his novel Lady Baltimore in 1906. The moist, fruit-and-nut-filled Lane Cake, named for Emma Rylander Lane of Clayton, Alabama, became a sensation in 1898. Mrs. Lane published the recipe in her cookbook, Some Good Things to Eat. It has been called the “Southern Belle” of cakes. Southerners are prone to associate cake making with love and friendly concern. -

Food Network Canada Takes Viewers on a Culinary Thrill Ride with Its Blockbuster Fall Slate

FOOD NETWORK CANADA TAKES VIEWERS ON A CULINARY THRILL RIDE WITH ITS BLOCKBUSTER FALL SLATE New Programming Debuts Every Day of the Week Including: I Hart Food, Beat Bobby Flay All-Star Takeover and Guy’s Family Road Trip Food Network Canada Available on National Free Preview for the Month of September For additional media material please visit the Corus Media Centre To share this release socially use: bit.ly/2fLuLdO For Immediate Release TORONTO, August 16, 2017 – This fall, Food Network Canada’s schedule is sweet, savoury and stuffed full of brand-new primetime premieres, cut-throat culinary competitions and indulgent daytime programming. Beginning August 28, viewers can look forward to new series and specials every day of the week, including I Hart Food, Beat Bobby Flay All-Star Takeover, Guy’s Family Road Trip, Texas Cake House, Dessert Games, Worst Cooks in America: Celebrity Edition, and returning favourites including Barefoot Contessa, Giada in Italy, Ginormous Food, and more. Lights, camera, cooking! Weeknights on Food Network Canada are full of fierce competitions, sizzling showdowns and sweet treats beginning with new four-part special Dessert Games premiering on August 28 at 9 p.m. ET/PT. In this new series, Guy Fieri hands over his grocery store’s keys to the ace of cakes Duff Goldman, who challenges four talented pastry chefs to shop, prepare and plate three amazing confectionary creations. The last chef remaining will win a sweet shopping spree worth up to $10,000. Next is decedent new series Texas Cake House, which highlights cake artist Natalie Sideserf and her husband Dave’s most intricate, over-the-top and edible creations starting August 28 at 10 p.m. -

Uses and Gratifications of the Food Network

San Jose State University SJSU ScholarWorks Master's Theses Master's Theses and Graduate Research 2009 Uses and gratifications of the oodF Network Cori Lynn Hemmah San Jose State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/etd_theses Recommended Citation Hemmah, Cori Lynn, "Uses and gratifications of the oodF Network" (2009). Master's Theses. 3657. DOI: https://doi.org/10.31979/etd.psmy-z22g https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/etd_theses/3657 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Master's Theses and Graduate Research at SJSU ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of SJSU ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. USES AND GRATIFICATIONS OF THE FOOD NETWORK A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the School of Journalism and Mass Communications San Jose State University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science by Cori Lynn Hemmah May 2009 UMI Number: 1470991 Copyright 2009 by Hemmah, Cori Lynn INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI® UMI Microform 1470991 Copyright 2009 by ProQuest LLC All rights reserved. -

The Southern Cook Book of Fine Old Recipes

"APPETITE - WHETTING, COMPETENT, DELICIOUS RECIPES THAT HAVE MADE SOUTHERN COOKING FAMOUS THE WORLD c OVER." Charlotte, N. C., News. From the collection of the o Prelinger i a JJibrary San Francisco, California 2006 THE SOUTHERN COOK BOOK OF FINE OLD RECIPES Compiled and Edited by Lillie S. Lnstig S. Claire Sondheii Sarah Rensel Decorations by H. Charles Kellui Copyrighted 1935 CULINARY ARTS PRESS P. O. Box 915, Reading, Pa. INDEX Page Page APPETIZERS CANDIES Avocado Canapes 47 Candied Orange or Grapefruit Peel 46 Cheese Appetizer for the Master's Caramels, Grandmother's 46 Cocktail 47 Cocoanut Pralines, Florida 46 Delicious Appetizer 47 Fudge, Aunt Sarah's 46 Papaya Canape 26 Goober Brittle 46 Papaya Cocktail 26 Pecan Fondant 46 Pigs in Blankets 47 Pralines, New Orleans 46 . Shrimp Avocado Cocktail 47 Shrimp Paste 18 EGGS BEVERAGES Creole Omelet 29 Eggs Biltmore Goldenrod 29 Egg Nog 48 Eggs, New Orleans 29 Idle Hour Cocktail 48 Eggs, Ponce de Leon 29 Mint Julep 48 Eggs Stuffed with Chicken Livers 29 Mint Tea 21 Orange Julep 48 FRITTERS, PANCAKES, WAFFLES Planter's Punch 48 and MUSH Spiced Cider 48 Apple Fritters 28 Syllabub, North Carolina 48 Apricot Fritters 28 Tom and Jerry, Southern Style 48 Corn Bread Fritters 28 Zazarac Cocktail . ... 48 Corn Fritters 28 Corn Meal Dodgers for Pot Likker 6 BREAD AND BISCUITS Corn Meal Mush 35 Flannel Cakes 32 Batter Bread, Mulatto Style Flapjacks, Georgia 32 Baking Powder Biscuits, Mammy's Fruit Fritter Batter 28 Beaten Biscuits Griddle Cakes 32 Buttermilk Muffins Griddle Cakes, Sour Milk 32 Cheese Biscuits Hoe Cake : 30 Miss Southern .. -

Sunday Morning Grid 1/25/15 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

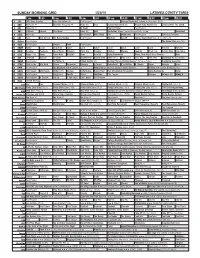

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 1/25/15 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program College Basketball Indiana at Ohio State. (N) Å 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News (N) Paid Detroit Auto Show (N) Mecum Auto Auction (N) Lindsey Vonn: The Climb 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program 7 ABC Outback Explore This Week News (N) NBA Basketball Miami Heat at Chicago Bulls. (N) Å Basketball 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 700 Club Telethon 11 FOX Paid Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday Paid Program Big East Tip-Off College Basketball Duke at St. John’s. (N) 13 MyNet Paid Program The Game Plan ›› (PG) 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local Transfor. Transfor. 24 KVCR Painting Dewberry Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexico Cooking Chefs Life Simply Ming Ciao Italia 28 KCET Raggs Cold. Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Biz Aging Backwards Things That Aren’t Here Anymore More 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Bucket-Dino Bucket-Dino Doki (TVY7) Doki (TVY7) Dive, Olly Dive, Olly Superman III ›› (1983) 34 KMEX Paid Program Al Punto (N) Fútbol Central (N) Mexico Primera Division Soccer: Pumas vs Toluca República Deportiva 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. -

Kathleen Finch Chief Lifestyle Brands Officer

Kathleen Finch Chief Lifestyle Brands Officer Kathleen Finch is Chief Lifestyle Brands Officer at Discovery, where she oversees the management oversight of HGTV, Food Network, TLC, ID, Travel Channel, DIY Network, Cooking Channel, Discovery Life, American Heroes Channel, Destination America, Great American Country and the company’s Digital Studios Group in the U.S. Previously, Finch was Chief Programming, Content & Brand Officer for all six Scripps Networks including all linear and digital media brands. She was promoted to this position in August of 2015 after serving as President of HGTV, DIY Network and Great American Country. During her tenure as President, Finch led the networks to record ratings and revenues. She launched such notable talent-driven series as Fixer Upper, Flip or Flop, Ellen’s Design Challenge featuring Ellen DeGeneres, The Property Brothers, Love It or List It, The Vanilla Ice Project and DIY Network Blog Cabin, the first ever interactive home renovation series produced on-air and online. Before joining HGTV, Finch spent seven years at the Food Network as Senior Vice President of Primetime Programming where she introduced long-running series such as Unwrapped, Food Network Challenge and Ace of Cakes. Prior to joining Scripps Networks in 1999, Finch was a journalist working in both broadcast and print. She spent 12 years as a CBS Network News producer, traveling the world to cover breaking news and events in locations such as Cuba and the UK. A graduate of Stanford University, Finch also participated in the CTAM Executive Management Program, WICT’s Betsy Magness Leadership Institute and the Scripps Leadership Institute and is a WICT and Multichannel News “Woman to Watch.” She’s also been named one of TIME’s “100 Industry Innovators to Watch” and featured in Broadcasting & Cable’s “The Next Wave: B&C’s Annual Salute to Women Who Make a Difference.” Most recently, Finch was named Adweek’s Television Executive of the Year for 2018. -

Christmas Cookie Recipes

Christmas Cookie Recipes Christmas Cookie Recipes A Delicious Collection of Christmas Cookie Recipes 1 - - Christmas Cookie Recipes You now have master resale rights to this publication. Legal Notice:- While every attempt has been made to verify the information provided in this recipe Ebook, neither the author nor the distributor assume any responsibility for errors or omissions. Any slights of people or organizations are unintentional and the Development of this Ebook is bona fide. This Ebook has been distributed with the understanding that we are not engaged in rendering technical, legal, accounting or other professional advice. We do not give any kind of guarantee about the accuracy of information provided. In no event will the author and/or marketer be liable for any direct, indirect, incidental, consequential or other loss or damage arising out of the use of this document by any person, regardless of whether or not informed of the possibility of damages in advance. Index 1:Balls Almond Snow Cookies Amish Ginger Cookies Bourbon Balls Buckeyes Cherry Nut Balls Cherry Pecan Drops Choco-Mint Snaps Chocolate Cherry Kris Kringles Chocolate Chip Mexican Wedding Cakes Chocolate Chip Tea Cookies Chocolate Chunk Snowballs Chocolate Orange Balls Chocolate Peanut Butter Crispy Balls Chocolate Rum Balls Christmas Casserole Cookies Coconut Balls Creme de Menthe Balls Double Chocolate Kisses Dreamsicle Cookies In a Jar Eggnog Snickerdoodles Eskimo Snowballs Gooey Butter Cookies Hazelnut Holiday Balls Healthy Feel-Good Chocolate Chip Balls 2 - - -

0ML SPOKANE DLYQ6.STY (Page 2)

(S) = In Stereo (N) = NewProgramming For 24-hour television listings, plus a guide to channel numbers on cable Tonight’s listings (HD) = High Definition Television (PA) = Parental Advisory Movies shaded Listings subject to change and satellite, look in the TV Week magazine in Sunday’s Spokesman-Re- (R) = Restricted Under 17 (NR) = Not Rated view. 5 pm 5:30 6 pm 6:30 7 pm 7:30 8 pm 8:30 9 pm 9:30 10 pm 10:30 11 pm 11:30 12 am KREM News (N) CBS Evening News- News (N) Access Hollywood The Doctors 4 The Big Bang The- How I Met Your Two and a Half Rules of Engage- CSI: Miami: Collateral Damage. (N) (S) 5 News (N) (:35) Late Show With David Letterman ^/2.1 Couric (N) 4 ory 4 Mother 5 Men 5 ment 5 (HD) (N) (S) 4 (HD) KXLY KXLY 4 News at 5 World News-Gib- KXLY 4 News at 6 KXLY 4 News at Entertainment The Insider (N) (S) Dancing With the Stars: The celebrities perform. (Same-day Tape) (S) 4 (HD) (:02) Castle: Little Girl Lost. (N) (S) 4 KXLY 4 News at 11 Nightline (HD) Jimmy Kimmel Live 4.1/4.3 (HD) son (HD) 6:30 (HD) Tonight 4 4 (HD) (HD) (HD) 5 KXMN News Storm Stories 3 Cops (S) 4 Cops (S) 4 News News Masters of Illusion (N) (S) (HD) Magic’s Biggest Secrets Finally Re- Entertainment The Insider (N) (S) Inside Edition 4 FX 2 (‘91, Action) (Bryan Brown, Rachel 4.2 vealed (N) (S) (HD) Tonight 4 4 (HD) Ticotin) (PG-13) KHQ News (N) 3 NBC Nightly News News (N) 3 Who Wants to Be a Jeopardy! (N) 3 Wheel of Fortune Deal or No Deal (N) (S) 4 Medium: How to Make a Killing in Big Business. -

Complete Recipes for the Boo

Introduction My name is Aren Lane and I am from the Grass Valley Creek 4-H club. This book is my Emerald Star Project for 2008. It is a collection of the above-average recipes from 4-H Favorite Foods Day since 1978. Favorite Foods Day is an annual 4-H County Event that is held the same day as 4-H Achievement Day. Kids bring their favorite foods. The 4-H members are separated into junior, intermediate, and senior categories. Each group is judged by three judges. They judge you on how well you present your food, how appealing your food is to the eye, and how good your food tastes. Although these recipes are excellent, some of the earlier ones didn’t include all of the ingredients needed to make the complete recipe, so where needed, I listed the missing ingredients in italics. However, overall I am confident that this recipe book is complete and contains both usual and unusual types of food. So I hope that you enjoy this book, and that you cook some top-notch food. Aren Lane Age 14 Douglas City April 2008 1 Table of Contents • Introduction 1 • Helpful recipes 3 • Appetizers 5 • Beverages 13 • Salads 17 • Soups 19 • Side dishes 24 • Main dishes 30 • Lasagnas 49 • Breads 55 • Desserts 61 • Pies 75 • Cakes 83 • Cheesecakes 93 • Brownies 99 • Cookies 105 2 Baked Pie Shell 2 and 2/3 cups flour 1 cup salted butter 1 tsp. salt 6 to 8 Tbsp. cold water In large bowl, mix flour, salt and butter, stir with a fork. -

Wednesday Morning, March 28

WEDNESDAY MORNING, MARCH 28 FRO 6:00 6:30 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 COM 4:30 KATU News This Morning (N) Good Morning America (N) (cc) AM Northwest (cc) The View 50 Cent; Vera Wang; Live! With Kelly Jessica Biel; Abi- 2/KATU 2 2 (cc) (Cont’d) Bone Hampton. (cc) (TV14) gail Breslin. (N) (cc) (TVPG) KOIN Local 6 at 6am (N) (cc) CBS This Morning (N) (cc) Let’s Make a Deal (N) (cc) (TVPG) The Price Is Right (N) (cc) (TVG) The Young and the Restless (N) (cc) 6/KOIN 6 6 (TV14) NewsChannel 8 at Sunrise at 6:00 Today The Hiring Our Heroes Today initiative. (N) (cc) Anderson (cc) (TVG) 8/KGW 8 8 AM (N) (cc) EXHALE: Core Wild Kratts (cc) Curious George Cat in the Hat Super Why! Dinosaur Train Sesame Street Gina teaches Sid the Science Clifford the Big Martha Speaks WordWorld (TVY) 10/KOPB 10 10 Fusion (TVG) (TVY) (TVY) Knows a Lot (TVY) (TVY) Marco about Spanish. (cc) (TVY) Kid (TVY) Red Dog (TVY) (TVY) Good Day Oregon-6 (N) Good Day Oregon (N) MORE Good Day Oregon The 700 Club (cc) (TVPG) Law & Order: Criminal Intent An ear 12/KPTV 12 12 surgeon’s murder. (TV14) International Fel- Paid Paid Paid Zula Patrol (cc) Pearlie (TVY7) Through the Bible International Fel- Paid Paid Paid Paid 22/KPXG 5 5 lowship (TVY) lowship Creflo Dollar (cc) John Hagee Breakthrough This Is Your Day Believer’s Voice Winning With 360 Degree Life Pro-Claim Behind the Joyce Meyer Life Today With Today: Marilyn & 24/KNMT 20 20 (TVG) Today (cc) (TVG) W/Rod Parsley (cc) (TVG) of Victory (cc) Wisdom (cc) Scenes (cc) James Robison Sarah Eye Opener (N) (cc) My Name Is Earl My Name Is Earl Swift Justice: Swift Justice: Maury (cc) (TV14) The Steve Wilkos Show (cc) (TVPG) 32/KRCW 3 3 (TV14) (TV14) Jackie Glass Jackie Glass Andrew Wom- Paid The Jeremy Kyle Show (N) (cc) America Now (cc) Divorce Court (N) Excused (cc) Excused (cc) Cheaters (cc) Cheaters (cc) America’s Court Judge Alex (N) 49/KPDX 13 13 mack (TVPG) (TVG) (TVPG) (TV14) (TV14) (TV14) (TV14) (cc) (TVPG) Paid Paid Dog the Bounty Hunter (cc) (TVPG) Dog the Bounty Hunter (cc) (TVPG) Criminal Minds Mayhem. -

Low-Iodine Cookbook by Thyca: Thyroid Cancer Survivors Association

Handy One-Page LID Summary—Tear-Out Copy For the detailed Free Low-Iodine Cookbook with hundreds of delicious recipes, visit www.thyca.org. Key Points This is a Low-Iodine Diet (“LID”), not a “No-Iodine Diet” or an “Iodine-Free Diet.” The American Thyroid Association suggests a goal of under 50 micrograms (mcg) of iodine per day. The diet is for a short time period, usually for the 2 weeks (14 days) before a radioactive iodine scan or treatment and 1-3 days after the scan or treatment. Avoid foods and beverages that are high in iodine (>20 mcg/serving). Eat any foods and beverages low in iodine (< 5 mcg/serving). Limit the quantity of foods moderate in iodine (5-20 mcg/serving). Foods to AVOID Foods to ENJOY • Iodized salt, sea salt, and any foods containing iodized • Fruit, fresh, frozen, or jarred, salt-free and without red salt or sea salt food dye; canned in limited quantities; fruit juices • Seafood and sea products (fish, shellfish, seaweed, • Vegetables: ideally raw or frozen without salt, except seaweed tablets, calcium carbonate from oyster shells, soybeans carrageenan, agar-agar, alginate, arame, dulse, • Beans: unsalted canned, or cooked from the dry state furikake, hiziki, kelp, kombu, nori, wakame, and other • Unsalted nuts and unsalted nut butters sea-based foods or ingredients) • Egg whites • Dairy products of any kind (milk, cheese, yogurt, • Fresh meats (uncured; no added salt or brine butter, ice cream, lactose, whey, casein, etc.) solutions) up to 6 ounces a day • Egg yolks, whole eggs, or foods containing them •