Our Foundering Fathers the Story of Kirkland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Document Analysis Questions

Captain John L. Anderson Document Analysis Instructions (2 image analysis and 2 SOAPS document analysis tools) Document Instructions Biography Read aloud, highlight significant information (who, what, when, and where) Document 1 How many steamboats? Anderson Steamboat Co. Ferry Schedule How many sailings? How many places does it travel? What does this document say about the Lake Washington steamboat business? What does this document say about the people who used the steamboats? What does this document say about transportation in general? Document 2 Complete image analysis graphic organizer Photograph of Anderson Shipyards 1908 Document 3 Complete image analysis graphic organizer Photograph of Anderson Shipyards 1917 Document 4 Complete SOAPS document analysis graphic organizer News article from Lake Washing- ton Reflector 1918 Document 5 Complete SOAPS document analysis graphic organizer News article from East Side Jour- nal 1919 How did the lowering of Lake Summarize all of the evidence you found in the documents. Washington impact Captain Anderson? Positive Negative Ferry Fay Burrows Document Analysis Instructions (2 image analysis and 3 SOAPS document analysis tools) Documents Instructions Biography Read aloud, highlight significant information (who, what, when, and where) Document 1 1. Why did Captain Burrows start a boat house? Oral History of Homer Venishnick Grandson of Ferry Burrows 2. How did he make money with the steam boat? 3. What fueled this ship? 4. What routes did Capt. Burrows take the steamboat to earn money? 5. What happened to the steamboat business when the lake was lowered? 6. What happened to North Renton when the lake was lowered? Document 2 1. What does “driving rafts” mean and how long did it take? Interview with Martha Burrows Hayes 2. -

September 2012

SEPTEMBERdecember 2012 2006 / / volume volume 25 19 issue issue 4 4 HEADED FOR THE ARCTIC The tugs Drew Foss, right, and Wedell Foss took the oil rig Noble Discoverer out of Seattle’s Elliott Bay on Wednesday, June 27, heading for Port Angeles to hand off the rig to the Lauren Foss, which towed it to Dutch Harbor. Alki Point is in the background. Numerous Foss tugs, two barges and a derrick are supporting a Shell Arctic drilling project. (See article on page 3.) NEW TUGS WILL OPEN The introduction ofMore three than new any 12 monthsannounced in the recent early in history the summer of our com- of a holiday greeting:“Arctic-Class” tugs by pany,Foss Maritime 2006 was a year2012, in which and constructionFoss Maritime of movedthe first forward OPPORTUNITIES IN will open new opportunitiesstrategically in the in all areaswill of startour business.early next year, bringing Strategic Moves in 2006oil and gas industry, broaden the additional jobs to the yard on the company’s capability to take on Columbia River. OIL AND GAS SECTOR We believe that new courses charted in our harbor services, Align Us with This Mission:projects in extreme environments, “At Foss we innovate,” said marine transportation/logistics and shipyard lines of business, Provide Customers withand Servicesensure continued growth of Foss Gary Faber, Foss’ president and chief while not without risk, will further the growth and success of that are Without EqualRainier Shipyard. operating officer. “These vessels will The plan to build thethe innovative, company for decadesbe built to come. using Continued the latest insideadvances in 130-foot ocean-going tugs was technology and equipment. -

New Yarns and Funny Jokes

f IMfWtMTYLIBRARY^)Of AUKJUNIA h SAMMMO ^^F -J) NEW YARNS AND COMPRISING ORIGINAL AND SELECTED MERIGAN * HUMOR WITH MANY LAUGHABLE ILLUSTRATIONS. Copyright, 1890, by EXCELSIOR PUBLISHING HOUSE. NEW YORK* EXCELSIOR PUBLISHING HOUSB, 29 & 3 1 Beekman Street EXCELSIOR PUBLISHING HOUSE, 29 &. 31 Beekman Street, New York, N. Y. PAYNE'S BUSINESS EDUCATOR AN- ED cyclopedia of the Knowl* edge necessary to the Conduct of Business, AMONG THE CONTENTS ARE: An Epitome of the Laws of the various States of the Union, alphabet- ically arranged for ready reference ; Model Business Letters and Answers ; in Lessons Penmanship ; Interest Tables ; Rules of Order for Deliberative As- semblies and Debating Societies Tables of Weights and Measures, Stand- ard and the Metric System ; lessons in Typewriting; Legal Forms for all Instruments used in Ordinary Business, such as Leases, Assignments, Contracts, etc., etc.; Dictionary of Mercantile Terms; Interest Laws of the United States; Official, Military, Scholastic, Naval, and Professional Titles used in U. S.; How to Measure Land ; in Yalue of Foreign Gold and Silver Coins the United states ; Educational Statistics of the World ; List of Abbreviations ; and Italian and Phrases Latin, French, Spanish, Words -, Rules of Punctuation ; Marks of Accent; Dictionary of Synonyms; Copyright Law of the United States, etc., etc., MAKING IN ALL THE MOST COMPLETE SELF-EDUCATOR PUBLISHED, CONTAINING 600 PAGES, BOUND IN EXTRA CLOTH. PRICE $2.00. N.B.- LIBERAL TERMS TO AGENTS ON THIS WORK. The above Book sent postpaid on receipt of price. Yar]Qs Jokes. ' ' A Natural Mistake. Well, Jim was champion quoit-thrower in them days, He's dead now, poor fellow, but Jim was a boss on throwing quoits. -

The Seattle Foundation Annual Report Donors & Contributors 3

2008 The Seattle Foundation Annual Report Donors & Contributors 3 Grantees 13 Fiscal Sponsorships 28 Financial Highlights 30 Trustees and Staff 33 Committees 34 www.seattlefoundation.org | (206) 622-2294 While the 2008 financial crisis created greater needs in our community, it also gave us reason for hope. 2008 Foundation donors have risen to the challenges that face King County today by generously supporting the organizations effectively working to improve the well-being of our community. The Seattle Foundation’s commitment to building a healthy community for all King County residents remains as strong as ever. In 2008, with our donors, we granted more than $63 million to over 2000 organizations and promising initiatives in King County and beyond. Though our assets declined like most investments nationwide, The Seattle Foundation’s portfolio performed well when benchmarked against comparable endowments. In the longer term, The Seattle Foundation has outperformed portfolios comprised of traditional stocks and bonds due to prudent and responsible stewardship of charitable funds that has been the basis of our investment strategy for decades. The Seattle Foundation is also leading efforts to respond to increasing need in our community. Late last year The Seattle Foundation joined forces with the United Way of King County and other local funders to create the Building Resilience Fund—a three-year, $6 million effort to help local people who have been hardest hit by the economic downturn. Through this fund, we are bolstering the capacity of selected nonprofits to meet increasing basic needs and providing a network of services to put people on the road on self-reliance. -

MV KALAKALA Other Names/Site Number Ferry PERALTA 2

NPS Form 10-900 (Oct. 1990) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in How to National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropne box or by entering the information requested. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property________________________________________ __ Historic name MV KALAKALA Other names/site number Ferry PERALTA 2. Location street & number Hylebos Creek Waterway, 1801 Taylor Way _____ not for publication city or town Tacorna_______________________ ___ vicinity State Washington code WA county Pierce_____ code 053 zip code 98421 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1986, as amended, I hereby certify that this _X nomination _ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Wsjpric Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property^C meets _ does not meet the National Register criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant _ nationally y^statewide _ locally. -

Seismic Stability of the Duwamish River Delta, Seattle, Washington

Seismic Stability of the Duwamish River Delta, Seattle, Washington Professional Paper 1661-E U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Other than this note, this page left intentionally blank. Earthquake Hazards of the Pacific Northwest Coastal and Marine Regions Robert Kayen, Editor Seismic Stability of the Duwamish River Delta, Seattle, Washington By Robert E. Kayen and Walter A. Barnhardt The delta front of the Duwamish River valley near Elliott Bay and Harbor Island is founded on young Holocene deposits shaped by sea-level rise, episodic volcanism, and seismicity. These river-mouth deposits are highly susceptible to seismic soil liquefac- tion and are potentially prone to submarine landsliding and disintegrative flow failure. Professional Paper 1661-E U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey ii U.S. Department of the Interior DIRK KEMPTHORNE, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Mark D. Myers, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2007 This report and any updates to it are available at: http://pubs.usgs.gov/pp/pp1661e/ For product and ordering information: World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS For more information on the USGS — the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment: World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS Manuscript approved for publication, May 29, 2007 Text edited by Peter Stauffer Layout by David R. Jones Suggested citation: Kayen, R.E., and Barnhardt, W.A., 2007, Seismic stability of the Duwamish River delta, Seattle, Washington: U.S. -

Anacortes Museum Research Files

Last Revision: 10/02/2019 1 Anacortes Museum Research Files Key to Research Categories Category . Codes* Agriculture Ag Animals (See Fn Fauna) Arts, Crafts, Music (Monuments, Murals, Paintings, ACM Needlework, etc.) Artifacts/Archeology (Historic Things) Ar Boats (See Transportation - Boats TB) Boat Building (See Business/Industry-Boat Building BIB) Buildings: Historic (Businesses, Institutions, Properties, etc.) BH Buildings: Historic Homes BHH Buildings: Post 1950 (Recommend adding to BHH) BPH Buildings: 1950-Present BP Buildings: Structures (Bridges, Highways, etc.) BS Buildings, Structures: Skagit Valley BSV Businesses Industry (Fidalgo and Guemes Island Area) Anacortes area, general BI Boat building/repair BIB Canneries/codfish curing, seafood processors BIC Fishing industry, fishing BIF Logging industry BIL Mills BIM Businesses Industry (Skagit Valley) BIS Calendars Cl Census/Population/Demographics Cn Communication Cm Documents (Records, notes, files, forms, papers, lists) Dc Education Ed Engines En Entertainment (See: Ev Events, SR Sports, Recreation) Environment Env Events Ev Exhibits (Events, Displays: Anacortes Museum) Ex Fauna Fn Amphibians FnA Birds FnB Crustaceans FnC Echinoderms FnE Fish (Scaled) FnF Insects, Arachnids, Worms FnI Mammals FnM Mollusks FnMlk Various FnV Flora Fl INTERIM VERSION - PENDING COMPLETION OF PN, PS, AND PFG SUBJECT FILE REVIEW Last Revision: 10/02/2019 2 Category . Codes* Genealogy Gn Geology/Paleontology Glg Government/Public services Gv Health Hl Home Making Hm Legal (Decisions/Laws/Lawsuits) Lgl -

Underrepresented Communities Historic Resource Survey Report

City of Madison, Wisconsin Underrepresented Communities Historic Resource Survey Report By Jennifer L. Lehrke, AIA, NCARB, Rowan Davidson, Associate AIA and Robert Short, Associate AIA Legacy Architecture, Inc. 605 Erie Avenue, Suite 101 Sheboygan, Wisconsin 53081 and Jason Tish Archetype Historic Property Consultants 2714 Lafollette Avenue Madison, Wisconsin 53704 Project Sponsoring Agency City of Madison Department of Planning and Community and Economic Development 215 Martin Luther King, Jr. Boulevard Madison, Wisconsin 53703 2017-2020 Acknowledgments The activity that is the subject of this survey report has been financed with local funds from the City of Madison Department of Planning and Community and Economic Development. The contents and opinions contained in this report do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the city, nor does the mention of trade names or commercial products constitute endorsement or recommendation by the City of Madison. The authors would like to thank the following persons or organizations for their assistance in completing this project: City of Madison Richard B. Arnesen Satya Rhodes-Conway, Mayor Patrick W. Heck, Alder Heather Stouder, Planning Division Director Joy W. Huntington Bill Fruhling, AICP, Principal Planner Jason N. Ilstrup Heather Bailey, Preservation Planner Eli B. Judge Amy L. Scanlon, Former Preservation Planner Arvina Martin, Alder Oscar Mireles Marsha A. Rummel, Alder (former member) City of Madison Muriel Simms Landmarks Commission Christina Slattery Anna Andrzejewski, Chair May Choua Thao Richard B. Arnesen Sheri Carter, Alder (former member) Elizabeth Banks Sergio Gonzalez (former member) Katie Kaliszewski Ledell Zellers, Alder (former member) Arvina Martin, Alder David W.J. McLean Maurice D. Taylor Others Lon Hill (former member) Tanika Apaloo Stuart Levitan (former member) Andrea Arenas Marsha A. -

Copy of Censusdata

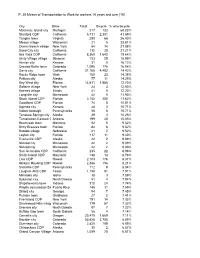

P. 30 Means of Transportation to Work for workers 16 years and over [16] City State Total: Bicycle % who bicycle Mackinac Island city Michigan 217 132 60.83% Stanford CDP California 5,711 2,381 41.69% Tangier town Virginia 250 66 26.40% Mason village Wisconsin 21 5 23.81% Ocean Beach village New York 64 14 21.88% Sand City city California 132 28 21.21% Isla Vista CDP California 8,360 1,642 19.64% Unity Village village Missouri 153 29 18.95% Hunter city Kansas 31 5 16.13% Crested Butte town Colorado 1,096 176 16.06% Davis city California 31,165 4,493 14.42% Rocky Ridge town Utah 160 23 14.38% Pelican city Alaska 77 11 14.29% Key West city Florida 14,611 1,856 12.70% Saltaire village New York 24 3 12.50% Keenes village Illinois 41 5 12.20% Longville city Minnesota 42 5 11.90% Stock Island CDP Florida 2,152 250 11.62% Goodland CDP Florida 74 8 10.81% Agenda city Kansas 28 3 10.71% Volant borough Pennsylvania 56 6 10.71% Tenakee Springs city Alaska 39 4 10.26% Tumacacori-Carmen C Arizona 199 20 10.05% Bearcreek town Montana 52 5 9.62% Briny Breezes town Florida 84 8 9.52% Barada village Nebraska 21 2 9.52% Layton city Florida 117 11 9.40% Evansville CDP Alaska 22 2 9.09% Nimrod city Minnesota 22 2 9.09% Nimrod city Minnesota 22 2 9.09% San Geronimo CDP California 245 22 8.98% Smith Island CDP Maryland 148 13 8.78% Laie CDP Hawaii 2,103 176 8.37% Hickam Housing CDP Hawaii 2,386 196 8.21% Slickville CDP Pennsylvania 112 9 8.04% Laughlin AFB CDP Texas 1,150 91 7.91% Minidoka city Idaho 38 3 7.89% Sykeston city North Dakota 51 4 7.84% Shipshewana town Indiana 310 24 7.74% Playita comunidad (Sa Puerto Rico 145 11 7.59% Dillard city Georgia 94 7 7.45% Putnam town Oklahoma 27 2 7.41% Fire Island CDP New York 191 14 7.33% Shorewood Hills village Wisconsin 779 57 7.32% Grenora city North Dakota 97 7 7.22% Buffalo Gap town South Dakota 56 4 7.14% Corvallis city Oregon 23,475 1,669 7.11% Boulder city Colorado 53,828 3,708 6.89% Gunnison city Colorado 2,825 189 6.69% Chistochina CDP Alaska 30 2 6.67% Grand Canyon Village Arizona 1,059 70 6.61% P. -

Washington State National Maritime Heritage Area Feasibility Study for Designation As a National Heritage Area

Washington State National Maritime Heritage Area Feasibility Study for Designation as a National Heritage Area WASHINGTON DEPARTMENT OF ARCHAEOLOGY AND HISTORIC PRESERVATION Washington State National Maritime Heritage Area Feasibility Study for Designation as a National Heritage Area WASHINGTON DEPARTMENT OF ARCHAEOLOGY AND HISTORIC PRESERVATION APRIL 2010 The National Maritime Heritage Area feasibility study was guided by the work of a steering committee assembled by the Washington State Department of Archaeology and Historic Preservation. Steering committee members included: • Dick Thompson (Chair), Principal, Thompson Consulting • Allyson Brooks, Ph.D., Department of Archaeology and Historic Preservation • Chris Endresen, Office of Maria Cantwell • Leonard Forsman, Chair, Suquamish Tribe • Chuck Fowler, President, Pacific Northwest Maritime Heritage Council • Senator Karen Fraser, Thurston County • Patricia Lantz, Member, Washington State Heritage Center Trust Board of Trustees • Flo Lentz, King County 4Culture • Jennifer Meisner, Washington Trust for Historic Preservation • Lita Dawn Stanton, Gig Harbor Historic Preservation Coordinator Prepared for the Washington State Department of Archaeology and Historic Preservation by Parametrix Berk & Associates March , 2010 Washington State NATIONAL MARITIME HERITAGE AREA Feasibility Study Preface National Heritage Areas are special places recognized by Congress as having nationally important heritage resources. The request to designate an area as a National Heritage Area is locally initiated, -

Phase 1 Final Report

AMHS GOVERNANCE STUDY Phase 1 Final Report Prepared for: Southeast Conference • Juneau, AK Ref: 16086-001-030-0 Rev. - December 31, 2016 Southeast Conference AMHS Governance Study 12/31/16 PREPARED BY Elliott Bay Design Group 5305 Shilshole Ave. NW, Ste. 100 Seattle, WA 98107 McDowell Group 9360 Glacier Hwy., Ste. 201 Juneau, AK 99801 NOTES Cover photo courtesy of Alaska Floats My Boat. ELLIOTT BAY DESIGN GROUP Job: 16086 By: RIW AMHS Reform Final Report.docx Rev. - Page: i Southeast Conference AMHS Governance Study 12/31/16 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Project Overview Phase One of the AMHS Strategic Operational and Business Plan was developed by Elliott Bay Design Group (EBDG) and McDowell Group. The study identified alternative governance structures that could help the Alaska Marine Highway System (AMHS) achieve financial sustainability. This statewide effort was managed by Southeast Conference and guided by a 12- member steering committee of stakeholders from across Alaska. Project tasks included a high-level examination of six basic ferry governance models to assess their suitability for Alaska’s unique geography, markets, and transportation needs. More detailed case studies were conducted with three ferry systems to identify ideas and lessons applicable to AMHS: British Columbia Ferry System, Steamship Authority (Massachusetts), and CalMac Ferries (Scotland). The study also included review of relevant AMHS reports and interviews with key AMHS contacts including senior management and union representatives. The project incorporated extensive public involvement including convening a Statewide Marine Transportation Summit, solicitation of feedback through the project website, outreach to municipal governments and trade organizations throughout Alaska, and a presentation and discussion at Southeast Conference Annual Meeting. -

An Oral History Project Catalogue

1 A Tribute to the Eastside “Words of Wisdom - Voices of the Past” An Oral History Project Catalogue Two 2 FORWARD Oral History Resource Catalogue (2016 Edition) Eastside Heritage Center has hundreds of oral histories in our permanent collection, containing hours of history from all around East King County. Both Bellevue Historical Society and Marymoor Museum had active oral history programs, and EHC has continued that trend, adding new interviews to the collection. Between 1996 and 2003, Eastside Heritage Center (formerly Bellevue Historical Society) was engaged in an oral history project entitled “Words of Wisdom – Voices of the Past.” As a part of that project, Eastside Heritage Center produced the first Oral History Resource Catalogue. The Catalogue is a reference guide for researchers and staff. It provides a brief introduction to each of the interviews collected during “Words of Wisdom.” The entries contain basic information about the interview date, length, recording format and participants, as well as a brief biography of the narrator, and a list of the topics discussed. Our second catalogue is a continuation of this project, and now includes some interviews collected prior to 1996. The oral history collection at the Eastside Heritage Center is constantly expanding, and the Catalogue will grow as more interviews are collected and as older interviews are transcribed. Special thanks to our narrators, interviewers, transcribers and all those who contributed their memories of the Eastside. We are indebted to 4Culture for funding this project. Eastside Heritage Center Oral History Committee 3 Table of Contents Forward and Acknowledgments pg. 2 Narrators Richard Bennett, with Helen Bennett Johnson pg.