Case 3:07-Md-00001-PAM-JRK Document 376 Filed 07/21/10 Page 1 of 26

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

COMPARISON of PRE- and POST- MPOUNDMENT GROUND-WATER LEVELS NEAR the WOODRUFF LOCK and DAM SITE, JACKSON COUNTY, FLORIDA Phillip N

COMPARISON OF PRE- AND POST- MPOUNDMENT GROUND-WATER LEVELS NEAR THE WOODRUFF LOCK AND DAM SITE, JACKSON COUNTY, FLORIDA Phillip N. Albertson AUTHOR: Hydrologist, U.S. Geological Survey, 3039 An-miler Road, Suite 130, Peachtree Business Center, Atlanta, GA 30360-2824. REFERENCE: Procet.dings of the 2001 Georgia Water Resources Conference, held March 26 - 27, 2001, at The University of Georgia, Kathryn J. Hatcher, editor, Institute of Ecology, The University of Georgia, Athens, Georgia. Abstract. In 1999, the U.S. Geological Survey The effect of filling the reservoir on ground-water (USGS) and the Georgia Department of Natural levels also is indicated by long-term water-level data Resources, Environmental Protection Division, began a from a well near Lake Seminole in Florida. Sporadic, cooperative study to investigate the hydrology and long-term water-level measurements began at this well hydrogeology of the Lake Seminole area, southwestern in 1950 and have continued during filling of the Georgia, and northwestern Florida. Lake Seminole is a reservoir (1954-1957) until 1982. These data indicate 37,500-acre impoundment that was created in 1954 by that the water level in this well has risen more than 10 the construction of the Jim Woodruff Lock and Dam feet since the filling of the reservoir. Prior to filling, the just south of the confluence of the Chattahoochee and hydraulic gradient at this location sloped east and Flint Rivers (fig. 1). Recent negotiations between the northeast to the Chattahoochee River. Now it slopes in a States of Alabama, Florida, and Georgia over water- southerly direction near the western end of Jim allocation rights have brought attention to the need for a Woodruff Lock and Dam and to the Apalachicola River. -

Economic Analysis of Critical Habitat Designation for the Fat Threeridge, Shinyrayed Pocketbook, Gulf Moccasinshell, Ochlockonee

ECONOMIC ANALYSIS OF CRITICAL HABITAT DESIGNATION FOR THE FAT THREERIDGE, SHINYRAYED POCKETBOOK, GULF MOCCASINSHELL, OCHLOCKONEE MOCCASINSHELL, OVAL PIGTOE, CHIPOLA SLABSHELL, AND PURPLE BANKCLIMBER Draft Final Report | September 12, 2007 prepared for: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 4401 N. Fairfax Drive Arlington, VA 22203 prepared by: Industrial Economics, Incorporated 2067 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02140 Draft – September 12, 2007 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ES-1T SECTION 1 INTRODUCTION AND FRAMEWORK FOR ANALYSIS 1-1 1.1 Purpose of the Economic Analysis 1-1 1.2 Background 1-2 1.3 Regulatory Alternatives 1-9 1.4 Threats to the Species and Habitat 1-9 1.5 Approach to Estimating Economic Effects 1-9 1.6 Scope of the Analysis 1-13 1.7 Analytic Time Frame 1-16 1.8 Information Sources 1-17 1.9 Structure of Report 1-18 SECTION 2 POTENTIAL CHANGES IN WATER USE AND MANAGEMENT FOR CONSERVATION OF THE SEVEN MUSSELS 2-1 2.1 Summary of Methods for Estimation of Economic Impacts Associated with Flow- Related Conservation Measures 2-2 2.2 Water Use in Proposed Critical Habitat Areas 2-3 2.3 Potential Changes in Water Use in the Flint River Basin 2-5 2.4 Potential Changes in Water Management in the Apalachicola River Complex (Unit 8) 2-10 2.5 Potential Changes in Water Management in the Santa Fe River Complex (Unit 11) 2-22 SECTION 3 POTENTIAL ECONOMIC IMPACTS RELATED TO CHANGES IN WATER USE AND MANAGEMENT 3-1 3.1 Summary 3-6 3.2 Potential Economic Impacts Related to Agricultural Water Uses 3-7 3.3 Potential Economic Impacts Related -

DIRECT TESTIMONY of PHILIP B. BEDIENT, Ph.D., P.E

No. 142, Original In The Supreme Court of the United States STATE OF FLORIDA, Plaintiff, v. STATE OF GEORGIA, Defendant. DIRECT TESTIMONY OF PHILIP B. BEDIENT, Ph.D., P.E. October 26, 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS SUMMARY OF OPINIONS .......................................................................................................... 1 BACKGROUND AND PROFESSIONAL QUALIFICATIONS .................................................. 6 ANY CHANGE IN THE AMOUNT OR TIMING OF STATE-LINE FLOW MUST BE COORDINATED AND EXECUTED BY THE CORPS ............................................................... 7 I. The Corps Operates the Federal Reservoir Projects in the ACF Basin as a Single, Integrated System to Balance Multiple Project Purposes ................................................... 9 II. The RIOP Controls Basin-Wide Storage and Releases of Water in the Federal Reservoirs ......................................................................................................................... 17 III. The Corps Operates Its Reservoir System as a Single Unit, and Under Low-Flow Conditions Offsets Increased Flint River Flows by Decreasing Chattahoochee River Releases ................................................................................................................... 25 IV. Increases in Basin Inflow Would Not Increase State-Line Flows into Florida During Low-Flow Conditions or Drought Operations...................................................... 26 REDUCTIONS IN GEORGIA’S WATER USE WOULD NOT RESULT IN INCREASED STATE-LINE FLOWS -

Simulated Effects of Impoundment of Lake Seminole on Ground-Water Flow in the Upper Floridan Aquifer in Southwestern Georgia and Adjacent Parts of Alabama and Florida

Simulated Effects of Impoundment of Lake Seminole on Ground-Water Flow in the Upper Floridan Aquifer in Southwestern Georgia and Adjacent Parts of Alabama and Florida Prepared in cooperation with the Georgia Department of Natural Resources Environmental Protection Division Georgia Geologic Survey Scientific Investigations Report 2004-5077 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Cover: Northern view of Jim Woodruff Lock and Dam from the west bank of the Apalachicola River. Photo by Dianna M. Crilley, U.S. Geological Survey. A. Map showing simulated flow net of the Upper Floridan aquifer in the lower Apalachicola-Chattahoochee-Flint River basin under hypothetical preimpoundment Lake Seminole conditions. B. Map showing simulated flow net of the Upper Floridan aquifer in the lower Apalachicola-Chattahoochee-Flint River basin under postimpoundment Lake Seminole conditions. Simulated Effects of Impoundment of Lake Seminole on Ground-Water Flow in the Upper Floridan Aquifer in Southwestern Georgia and Adjacent Parts of Alabama and Florida By L. Elliott Jones and Lynn J. Torak Prepared in cooperation with the Georgia Department of Natural Resources Environmental Protection Division Georgia Geologic Survey Atlanta, Georgia Scientific Investigations Report 2004-5077 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior Gale A. Norton, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Charles G. Groat, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2004 This report is available on the World Wide Web at http://infotrek.er.usgs.gov/pubs/ For more information about the USGS and its products: Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov/ Any use of trade, product, or firm names in this publication is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. -

Equitable Apportionment of the Apalachicola-Chattahoochee-Flint River Basin

Florida State University Law Review Volume 36 Issue 4 Article 6 2009 A Tale of Three States: Equitable Apportionment of the Apalachicola-Chattahoochee-Flint River Basin Alyssa S. Lathrop [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.law.fsu.edu/lr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Alyssa S. Lathrop, A Tale of Three States: Equitable Apportionment of the Apalachicola-Chattahoochee- Flint River Basin, 36 Fla. St. U. L. Rev. (2009) . https://ir.law.fsu.edu/lr/vol36/iss4/6 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Florida State University Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW A TALE OF THREE STATES: EQUITABLE APPORTIONMENT OF THE APALACHICOLA-CHATTHOOCHEE-FLINT RIVER BASIN Alyssa S. Lothrop VOLUME 36 SUMMER 2009 NUMBER 4 Recommended citation: Alyssa S. Lothrop, A Tale of Three States: Equitable Apportionment of the Apalachicola-Chatthoochee-Flint River Basin, 36 FLA. ST. U. L. REV. 865 (2009). COMMENT A TALE OF THREE STATES: EQUITABLE APPORTIONMENT OF THE APALACHICOLA- CHATTAHOOCHEE-FLINT RIVER BASIN ALYSSA S. LATHROP* I. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................. 865 II. ATRAGEDY OF THE COMMONS:THE ACF RIVER BASIN .................................... 866 A. History and the Beginning of the Conflict ................................................. 867 B. The ACF Compact: A Failed Attempt to Resolve ....................................... 870 C. A Tangled Web of Litigation ...................................................................... 871 D. Current Status of the Water War ............................................................... 873 E. A New Kind of Water War Rages On ......................................................... 877 III. SOME BACKGROUND:WATER LAW &EQUITABLE APPORTIONMENT ................. -

Water-Level Decline in the Apalachicola River, Florida, from 1954 to 2004, and Effects on Floodplain Habitats

Water-Level Decline in the Apalachicola River, Florida, from 1954 to 2004, and Effects on Floodplain Habitats By Helen M. Light1, Kirk R. Vincent2, Melanie R. Darst1, and Franklin D. Price3 1 U.S. Geological Survey, 2010 Levy Avenue, Tallahassee, Florida 32310. 2 U.S. Geological Survey, 3215 Marine , E-127, Boulder, Colorado 80303. 3 Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission, 350 Carroll Street, Eastpoint, Florida 32328. Prepared in cooperation with the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission Northwest Florida Water Management District Florida Department of Environmental Protection U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Scientific Investigations Report 2006-5173 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior Dirk Kempthorne, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey P. Patrick Leahy, Acting Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2006 For product and ordering information: World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS For more information on the USGS--the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment: World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this report is in the public domain, permission must be secured from the individual copyright owners to reproduce any copyrighted materials contained within this report. Suggested citation: Light, H.M., Vincent, K.R., Darst, M.R., and Price, F.D., 2006, Water-Level Decline in the Apalachicola River, Florida, from 1954 to 2004, and Effects on Floodplain Habitats: U.S. -

State and Regional Water Management and Planning

State and Regional Water Management and Planning Florida Water Laws Seminar Webinar: 8/20/20 Frederick L. Aschauer, Jr. Nicole Poot Lewis, Longman & Walker, P.A. Outline Surface water resources Groundwater resources Regional water planning Florida v. Georgia Mississippi v. Tennessee Legal Disclaimer: There will be a test Florida’s Constitution “It shall be the policy of the state to conserve and protect its natural resources and scenic beauty. Adequate provision shall be made by law for the abatement of air and water pollution and of excessive and unnecessary noise and for the conservation and protection of natural resources.” Art. II, § 7, Fla. Const. The regulation of surface water Surface water discharges FDEP Chap. 403, Florida Statutes 403.0885, Florida Statutes In October 2000, EPA authorized the Florida Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) to implement the NPDES stormwater permitting program in the state of Florida. FDEP's authority to administer the NPDES program is set forth in Section 403.0885, Florida Statutes The NPDES stormwater program regulates point source discharges of stormwater into surface waters of the state of Florida from certain municipal, industrial and construction activities. Permits required Surface water withdrawals WMDs (or FDEP) Chap. 373, Florida Statutes Chap. 40, Florida Administrative Code Permits required The regulation of groundwater Groundwater discharges FDEP Chap. 403, Florida Statutes Chap. 62-520, Florida Administrative Code Permits required Groundwater withdrawals WMDs Chap. 373, Florida Statutes Chap. 40, Florida Administrative Code Permits required Regional water planning 373.709, Florida Statutes Sets forth the requirements for Regional Water Supply Plans (RWSP) RWSP are updated every 5 years and cover a 20 year planning period The plan itself sets forth a framework for water supply management decisions. -

Long Term Hydrological Changes in the Apalachicola River, Florida

Review Article Int J Environ Sci Nat Res Volume 19 Issue 5 - June 2019 DOI: 10.19080/IJESNR.2019.19.556025 Copyright © All rights are reserved by Sanjeev Joshi Long Term Hydrological Changes in the Apalachicola River, Florida Sanjeev Joshi* Grazing land Research Laboratory, USDA-ARS, USA Submission: Published: *Corresponding March author: 20, 2019; June 07, 2019 Sanjeev Joshi, Post-doctoral Research Associate, Grazingland Research Laboratory, USDA-ARS, El Reno, Oklahoma; USA Abstract This short review extensively synthesizes information available in the long-term hydrologic changes experienced by the Apalachicola River in Florida, throughout its reach. Hydrologic changes in this river were induced by human interference along the river reach. The changes mostly include spatiotemporal alterations in the water levels and discharge regimes of the river. These changes have specifically reduced variability in its stages and flow regimes at several locations along its reach. The reduced variability of these important hydrological components could impact the adjoining floodplain ecosystem negatively. Therefore, ongoing river restoration efforts should focus on mimicking the natural historical hydrologyKeywords: in the river. Hydrologic changes; Water levels; Discharge; Apalachicola river Introduction Numerous rivers around the world have experienced long The Apalachicola River (described extensively in the “Study Area” section below) in Florida has also experienced long term term artificial changes in their hydrology [1,2]. These changes are hydrologic change due to anthropogenic interferences. Previous induced by engineering structures (such as dams and reservoirs) studies have quantified long term stage and discharge changes [1-3], navigation [4,5], waste disposal [6], channelization, and in the river [21,24-26]; however, information available in construction of levees and canals [7]; and have altered the river this regard has not been synthesized properly till date. -

Physical and Hydrochemical Evidence of Lake Leakage Near Jim

Physical and Hydrochemical Evidence of Lake Leakage near Jim Woodruff Lock and Dam and of Ground-Water Inflow to Lake Seminole, and an Assessment of Karst Features in and near the Lake, Southwestern Georgia and Northwestern Florida Prepared in cooperation with the Georgia Department of Natural Resources Environmental Protection Division Scientific Investigations Report 2005-5084 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Cover photographs, clockwise from top left: Boat-mounted acoustic Doppler current profiling apparatus in use near the River Boil; looking north from Apalachicola River toward Jim Woodruff Lock and Dam in background. Photograph by Lynn J. Torak, U.S. Geological Survey River Boil on Apalachicola River, about 900 feet downstream of Jim Woodruff Lock and Dam, near Chattahoochee, Florida. Photograph by Lynn J. Torak, U.S. Geological Survey Vortex flow entering sinkhole in the bottom on Lake Seminole at a depth from about 8 to 10 feet, located along the western shore of the lake about one-half mile from Jim Woodruff Lock and Dam near Sneads, Florida. Photograph by Harley Means, Florida Geological Survey Nonisokinetic thief sampler (Van Dorn sampler) in use at State Dock Spring on Flint River impoundment arm of Lake Seminole, Bainbridge, Georgia. Photograph by Lynn J. Torak, U.S. Geological Survey Physical and Hydrochemical Evidence of Lake Leakage near Jim Woodruff Lock and Dam and of Ground-Water Inflow to Lake Seminole, and an Assessment of Karst Features in and near the Lake, Southwestern Georgia and Northwestern Florida By Lynn J. Torak, Dianna M. Crilley, and Jaime A. Painter Prepared in cooperation with the Georgia Department of Natural Resources Environmental Protection Division Scientific Investigations Report 2005–5084 U.S. -

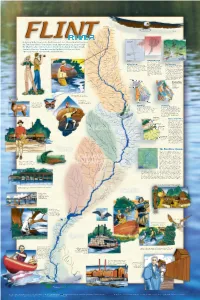

The Flint River System WOLF CR

ATLANTA EAST POINT COLLEGE PARK HAPEVILLE FOREST PARK Bald Eagle RED OAK MORROW RIVERDALE FIFE KENWOOD JONESBORO ORRS TYRONE SHOAL CR. PEACHTREE CITY COLLECTING SYSTEM Beginning in the heart of the 4-million-population Atlanta Metropolitan Area, FAYETTEVILLE LOVEJOY the Flint River flows 349 miles in a wide eastward arc to its junction with the Chattahoochee River at Lake Seminole in Southwest Georgia. At Lake EAST NEWNAN INMAN WOOLSEY RAYMOND WHITEWATER CR. STARRS MILL Seminole these two rivers become the Apalachicola River and flow SHARPSBURG SUNNY SIDE TURIN LOWRY MORELAND SENOIA 106 miles through Florida to the Gulf of Mexico. BROOKS LINE CR. LINE WHITE OAK CR VAUGHN TRANSPORTING GRIFFIN SYSTEM HARALSON LUTHERSVILLE ROVER WILLIAMSON ROCKY MOUNT ALVATON HOLLONVILLE DISPERSING Tributary Network RED OAK CR. SYSTEM One of the most surprising BIRCHJOLLY CR. characteristics of a river system is ZEBULON the intricate tributary network OAKLAND CONCORD A River System The Watershed that makes up the collecting GAY A river system is a network of connecting A ridge of high ground borders every channels. Water from rain, snow, groundwater system. This detail does not show river system. This ridge encloses what is ELKINS CR. and other sources collects into the channels the entire network, only a tiny called a watershed. Beyond the ridge, MEANSVILLE and flows to the ocean. A river system has portion of it. Even the smallest LIFSEY ALDORA all water flows into another river system. GREENVILLE MOLENA SPRINGS three parts: a collecting system, a transporting tributary has its own system of IMLAC VEGA Just as water in a bowl flows downward PIEDMONT system and a dispersing system. -

November 15, 2016 No. 142, Original in the Supreme Court of the United

No. 142, Original In the Supreme Court of the United States STATE OF FLORIDA, Plaintiff, v. STATE OF GEORGIA, Defendant. Before the Special Master Hon. Ralph I. Lancaster UPDATED PRE-FILED DIRECT TESTIMONY OF FLORIDA WITNESS DR. PETER SHANAHAN PAMELA JO BONDI GREGORY G. GARRE ATTORNEY GENERAL, STATE OF FLORIDA Counsel of Record PHILIP J. PERRY JONATHAN L. WILLIAMS CLAUDIA M. O’BRIEN DEPUTY SOLICITOR GENERAL ABID R. QURESHI JONATHAN GLOGAU JAMIE L. WINE SPECIAL COUNSEL LATHAM & WATKINS LLP OFFICE OF THE ATTORNEY GENERAL 555 11th Street, NW Suite 1000 FREDERICK L. ASCHAUER, JR. Washington, DC 20004 GENERAL COUNSEL Tel.: (202) 637-2207 FLORIDA DEPARTMENT OF [email protected] ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION PAUL N. SINGARELLA LATHAM & WATKINS LLP CHRISTOPHER M. KISE JAMES A. MCKEE ADAM C. LOSEY FOLEY & LARDNER LLP MATTHEW Z. LEOPOLD CARLTON FIELDS JORDEN BURT P.A. ATTORNEYS FOR THE STATE OF FLORIDA November 15, 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION..........................................................................................................................1 I. PROFESSIONAL BACKGROUND ................................................................................6 II. KEY TERMINOLOGY & CONCEPTS .........................................................................8 III. KEY BACKGROUND ON THE ACF RIVER BASIN SYSTEM ..............................10 A. System storage in the ACF Basin is physically constrained such that most water flowing into the river basin is passed through to Florida.............11 B. The Corps’ operational -

Chattahoochee-Flint River Basin, Alabama, Florida, and Georgia, 2010, and Water-Use Trends, 1985–2010

National Water Census Program Water Use in the Apalachicola-Chattahoochee-Flint River Basin, Alabama, Florida, and Georgia, 2010, and Water-Use Trends, 1985–2010 Scientific Investigations Report 2016 –5007 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey A B D C E F G H J K I Cover. All photographs by Alan M. Cressler, U.S. Geological Survey, unless noted otherwise. A, Dicks Creek, Lumpkin County, Georgia. B, Chicken farm, White County, Georgia. C, Kayaker, Chattahoochee River, Georgia. D, Storm-sewer overflow. E, Housing areas, Douglas County, Georgia. F, Waterfront, Columbus, Georgia. G, Center-pivot irrigation west of Albany, Georgia (Google earth, image from USDA Farm Service Agency, December 31, 2009). H, Cattle, Dooly County, Georgia. I, Big Rainbow mussel. J, Jim Woodruff Dam, Lake Seminole. K, Hole In The Wall cave, Merritts Pond, Marianna, Florida. Water Use in the Apalachicola- Chattahoochee-Flint River Basin, Alabama, Florida, and Georgia, 2010, and Water-Use Trends, 1985–2010 By Stephen J. Lawrence National Water Census Program Scientific Investigations Report 2016 –5007 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior SALLY JEWELL, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Suzette M. Kimball, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2016 For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment—visit http://www.usgs.gov or call 1–888–ASK–USGS. For an overview of USGS information products, including maps, imagery, and publications, visit http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod/. Any use of trade, firm, or product names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S.