Economic Analysis of Critical Habitat Designation for the Fat Threeridge, Shinyrayed Pocketbook, Gulf Moccasinshell, Ochlockonee

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

COMPARISON of PRE- and POST- MPOUNDMENT GROUND-WATER LEVELS NEAR the WOODRUFF LOCK and DAM SITE, JACKSON COUNTY, FLORIDA Phillip N

COMPARISON OF PRE- AND POST- MPOUNDMENT GROUND-WATER LEVELS NEAR THE WOODRUFF LOCK AND DAM SITE, JACKSON COUNTY, FLORIDA Phillip N. Albertson AUTHOR: Hydrologist, U.S. Geological Survey, 3039 An-miler Road, Suite 130, Peachtree Business Center, Atlanta, GA 30360-2824. REFERENCE: Procet.dings of the 2001 Georgia Water Resources Conference, held March 26 - 27, 2001, at The University of Georgia, Kathryn J. Hatcher, editor, Institute of Ecology, The University of Georgia, Athens, Georgia. Abstract. In 1999, the U.S. Geological Survey The effect of filling the reservoir on ground-water (USGS) and the Georgia Department of Natural levels also is indicated by long-term water-level data Resources, Environmental Protection Division, began a from a well near Lake Seminole in Florida. Sporadic, cooperative study to investigate the hydrology and long-term water-level measurements began at this well hydrogeology of the Lake Seminole area, southwestern in 1950 and have continued during filling of the Georgia, and northwestern Florida. Lake Seminole is a reservoir (1954-1957) until 1982. These data indicate 37,500-acre impoundment that was created in 1954 by that the water level in this well has risen more than 10 the construction of the Jim Woodruff Lock and Dam feet since the filling of the reservoir. Prior to filling, the just south of the confluence of the Chattahoochee and hydraulic gradient at this location sloped east and Flint Rivers (fig. 1). Recent negotiations between the northeast to the Chattahoochee River. Now it slopes in a States of Alabama, Florida, and Georgia over water- southerly direction near the western end of Jim allocation rights have brought attention to the need for a Woodruff Lock and Dam and to the Apalachicola River. -

11-1 335-6-11-.02 Use Classifications. (1) the ALABAMA RIVER BASIN Waterbody from to Classification ALABAMA RIVER MOBILE RIVER C

335-6-11-.02 Use Classifications. (1) THE ALABAMA RIVER BASIN Waterbody From To Classification ALABAMA RIVER MOBILE RIVER Claiborne Lock and F&W Dam ALABAMA RIVER Claiborne Lock and Alabama and Gulf S/F&W (Claiborne Lake) Dam Coast Railway ALABAMA RIVER Alabama and Gulf River Mile 131 F&W (Claiborne Lake) Coast Railway ALABAMA RIVER River Mile 131 Millers Ferry Lock PWS (Claiborne Lake) and Dam ALABAMA RIVER Millers Ferry Sixmile Creek S/F&W (Dannelly Lake) Lock and Dam ALABAMA RIVER Sixmile Creek Robert F Henry Lock F&W (Dannelly Lake) and Dam ALABAMA RIVER Robert F Henry Lock Pintlala Creek S/F&W (Woodruff Lake) and Dam ALABAMA RIVER Pintlala Creek Its source F&W (Woodruff Lake) Little River ALABAMA RIVER Its source S/F&W Chitterling Creek Within Little River State Forest S/F&W (Little River Lake) Randons Creek Lovetts Creek Its source F&W Bear Creek Randons Creek Its source F&W Limestone Creek ALABAMA RIVER Its source F&W Double Bridges Limestone Creek Its source F&W Creek Hudson Branch Limestone Creek Its source F&W Big Flat Creek ALABAMA RIVER Its source S/F&W 11-1 Waterbody From To Classification Pursley Creek Claiborne Lake Its source F&W Beaver Creek ALABAMA RIVER Extent of reservoir F&W (Claiborne Lake) Beaver Creek Claiborne Lake Its source F&W Cub Creek Beaver Creek Its source F&W Turkey Creek Beaver Creek Its source F&W Rockwest Creek Claiborne Lake Its source F&W Pine Barren Creek Dannelly Lake Its source S/F&W Chilatchee Creek Dannelly Lake Its source S/F&W Bogue Chitto Creek Dannelly Lake Its source F&W Sand Creek Bogue -

Chapter 335-6-11 Water Use Classifications for Interstate and Intrastate Waters

Environmental Management Chapter 335-6-11 DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT WATER DIVISION - WATER QUALITY PROGRAM ADMINISTRATIVE CODE CHAPTER 335-6-11 WATER USE CLASSIFICATIONS FOR INTERSTATE AND INTRASTATE WATERS TABLE OF CONTENTS 335-6-11-.01 The Use Classification System 335-6-11-.02 Use Classifications 335-6-11-.01 The Use Classification System. (1) Use classifications utilized by the State of Alabama are as follows: Outstanding Alabama Water ................... OAW Public Water Supply ......................... PWS Swimming and Other Whole Body Shellfish Harvesting ........................ SH Fish and Wildlife ........................... F&W Limited Warmwater Fishery ................... LWF Agricultural and Industrial Water Supply ................................ A&I (2) Use classifications apply water quality criteria adopted for particular uses based on existing utilization, uses reasonably expected in the future, and those uses not now possible because of correctable pollution but which could be made if the effects of pollution were controlled or eliminated. Of necessity, the assignment of use classifications must take into consideration the physical capability of waters to meet certain uses. (3) Those use classifications presently included in the standards are reviewed informally by the Department's staff as the need arises, and the entire standards package, to include the use classifications, receives a formal review at least once every three years. Efforts currently underway through local 201 planning projects will provide additional technical data on certain waterbodies in the State, information on treatment alternatives, and applicability of various management techniques, which, when available, will hopefully lead to new decisions regarding use classifications. Of particular interest are those segments which are currently classified for any usage which has an associated Supp. -

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Regulatory Program in Georgia

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Regulatory Program in Georgia David Lekson, PWS Kelly Finch, PWS Richard Morgan Savannah District August, 2013 US Army Corps of Engineers BUILDING STRONG® Topics § Savannah District Regulatory Division § Regulatory Efficiencies § On the Horizon 2 BUILDING STRONG® Introduction § Joined Savannah District in Jan 2013 § 25 years as Branch Chief in the Wilmington District, NC § Certified Professional Wetland Scientist with extensive field and teaching experience across the country § Participated in regional and national initiatives (wetland delineation and assessment, Mitigation/Banking); Served 6- month detail at the Pentagon in 2012 § Evaluated phosphate/sand/rock mining, wind energy, port and military projects, water supply, landfills, utilities, transportation (highway, airport, rail), and other large-scale commercial and residential projects 3 BUILDING STRONG® Georgia § Largest state east of the Mississippi River TN NC § 59,425 Square miles § Abuts 5 states § 5 Ecoregions SC § 159 Counties AL § 70,000 Miles of waterways § 7.7 Million acres of wetlands FL 4 BUILDING STRONG® Savannah Regulatory Organization Lake Lanier Piedmont Branch Mr. Ed Johnson (678) 422-2722 Morrow Coastal Branch Ms. Kelly Finch (912) 652-5503 Savannah Albany § 35 Team members § 3 Field Offices & Savannah § 3 Branches (Piedmont, Coastal, Multipurpose Management) 5 BUILDING STRONG® Regulatory Efficiencies § General Permits ► Re-issuance of existing Regional and Programmatic General Permits ► New RGP37 for Inshore GADNR Artificial Reefs -

Suwannee River State Park

HISTORY AND NATURE SUWANNEE RIVER The park contains over 1,800 acres of natural STATE PARK Florida with many features such as sinks, streams, 3631 201st Path SUWANNEE RIVER springs, limestone outcroppings and the rivers. Live Oak, FL 32060 STATE PARK The park has an abundance of plant and animal 386-362-2746 species including gopher tortoise, fox, deer, song Where the scenic Withlacoochee birds, wildflowers and diverse native forests. The joins the historic Suwannee protected Gulf Sturgeon and other fishes and reptiles are abundant in the river. PARK GUIDELINES Early use by Native Americans dates back some • Hours are 8 a.m. until sunset, 365 days a year. 12,000 years. While under Spanish control, the • An entrance fee is required. passage of De Soto’s party occurred in 1540. During • All plants, animals and park property are 1818 Andrew Jackson lead American forces through protected. Collection, destruction or disturbance this area searching for Indian strongholds, believed is prohibited. responsible for raiding settlers. • Pets are permitted in designated areas only. Pets Vestiges of history in the park show how important must be kept on a handheld leash no longer the Suwannee River was to Florida history. One can than six feet and well-behaved at all times. find an earthworks mound built during the Civil • Fishing, boating and fires are allowed in War to defend the railroad crossing that supplied designated areas only. A Florida fishing license confederate troops. The Battle of Olustee in may be required. February 1864 turned back Union forces heading west to destroy this bridge. -

Streamflow Maps of Georgia's Major Rivers

GEORGIA STATE DIVISION OF CONSERVATION DEPARTMENT OF MINES, MINING AND GEOLOGY GARLAND PEYTON, Director THE GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Information Circular 21 STREAMFLOW MAPS OF GEORGIA'S MAJOR RIVERS by M. T. Thomson United States Geological Survey Prepared cooperatively by the Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior, Washington, D. C. ATLANTA 1960 STREAMFLOW MAPS OF GEORGIA'S MAJOR RIVERS by M. T. Thomson Maps are commonly used to show the approximate rates of flow at all localities along the river systems. In addition to average flow, this collection of streamflow maps of Georgia's major rivers shows features such as low flows, flood flows, storage requirements, water power, the effects of storage reservoirs and power operations, and some comparisons of streamflows in different parts of the State. Most of the information shown on the streamflow maps was taken from "The Availability and use of Water in Georgia" by M. T. Thomson, S. M. Herrick, Eugene Brown, and others pub lished as Bulletin No. 65 in December 1956 by the Georgia Department of Mines, Mining and Geo logy. The average flows reported in that publication and sho\vn on these maps were for the years 1937-1955. That publication should be consulted for detailed information. More recent streamflow information may be obtained from the Atlanta District Office of the Surface Water Branch, Water Resources Division, U. S. Geological Survey, 805 Peachtree Street, N.E., Room 609, Atlanta 8, Georgia. In order to show the streamflows and other features clearly, the river locations are distorted slightly, their lengths are not to scale, and some features are shown by block-like patterns. -

July 3-9, 2011

Department of Natural Resources Wildlife Resources Division Law Enforcement Section Field Operations Weekly Report July 3-9, 2011 This report is a broad sampling of events that have taken place in the past week, but does not include all actions taken by the Law Enforcement Section. Region I- Calhoun (Northwest) FLOYD COUNTY On Sunday June 26th, Cpl. Shawn Elmore was working along the Etowah River in Rome and overheard radio traffic from Rome PD about a vehicle getting broken into at the Etowah River boat ramp. Cpl. Elmore responded to the boat ramp and assisted Rome PD officer. Cpl. Elmore located one of the suspects hiding in the woods and the other suspect came out of the river. Three juvenile suspects were detained and charged with entering an auto and criminal damage to property by Rome PD. On June 26th, Cpl. Shawn Elmore was at the Heritage Park boat ramp on the Coosa River in Rome when he was approached by a parent of four teenagers that were caught in a storm on the Etowah River. Cpl. Elmore went to get his patrol vessel and while enroute to the Etowah River boat ramp the four teens called the parents and advised they had gotten out of the river safely and were waiting on a ride on Turner Chapel Rd. On the night of June 26th, Cpl. Shawn Elmore received a call from Floyd E911 about 3 adults and a 3 year-old child stranded on the Etowah River. Cpl. Elmore responded to the scene and assisted Rome/Floyd Fire with a search of the river and the four were located and safely returned to their vehicle. -

Case 3:07-Md-00001-PAM-JRK Document 376 Filed 07/21/10 Page 1 of 26

Case 3:07-md-00001-PAM-JRK Document 376 Filed 07/21/10 Page 1 of 26 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT MIDDLE DISTRICT OF FLORIDA In re Tri-State Water Rights Litigation Case No. 3:07-md-01 (PAM/JRK) MEMORANDUM AND ORDER In Phase 2 of this Multi-District Litigation (“MDL”), the Court must evaluate the actions of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (the “Corps”) in light of the requirements of the National Environmental Policy Act (“NEPA”), 42 U.S.C. § 4321 et seq., the Endangered Species Act (“ESA”), 16 U.S.C. § 1531 et seq., and other similar statutes. Phase 1 of the litigation involved challenges to the Corps’s operations at the northernmost dam and reservoir in the Apalachicola-Chattahoochee-Flint (“ACF”) river basin. Phase 2 challenges those operations at the southernmost dam in the system, the Jim Woodruff Dam, which is located on the Apalachicola River at the border of Georgia and Florida. The parties in this Phase are: the states of Alabama, Florida, and Georgia; the Southeastern Federal Power Customers (“SeFPC”); the cities of Apalachicola, Florida, and Atlanta, Columbus, and Gainesville, Georgia; the Georgia counties of Gwinnett, DeKalb, and Fulton; the Atlanta Regional Commission (“ARC”); the Cobb County-Marietta Water Authority; the Board of Water Commissioners of Columbus, Georgia, doing business as the Columbus Water Works (“CWW”); the Lake Lanier Association;1 the Alabama Power 1 The Court will refer to Atlanta, Gainesville, Gwinnett County, DeKalb County, Fulton County, the ARC, the Cobb County-Marietta Water Authority, and the Lake Lanier Association collectively as “the Georgia parties.” The city of Columbus and the CWW Case 3:07-md-00001-PAM-JRK Document 376 Filed 07/21/10 Page 2 of 26 Company (“APC”); the Apalachicola Bay and River Keeper, Inc. -

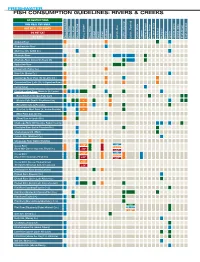

Fish Consumption Guidelines: Rivers & Creeks

FRESHWATER FISH CONSUMPTION GUIDELINES: RIVERS & CREEKS NO RESTRICTIONS ONE MEAL PER WEEK ONE MEAL PER MONTH DO NOT EAT NO DATA Bass, LargemouthBass, Other Bass, Shoal Bass, Spotted Bass, Striped Bass, White Bass, Bluegill Bowfin Buffalo Bullhead Carp Catfish, Blue Catfish, Channel Catfish,Flathead Catfish, White Crappie StripedMullet, Perch, Yellow Chain Pickerel, Redbreast Redhorse Redear Sucker Green Sunfish, Sunfish, Other Brown Trout, Rainbow Trout, Alapaha River Alapahoochee River Allatoona Crk. (Cobb Co.) Altamaha River Altamaha River (below US Route 25) Apalachee River Beaver Crk. (Taylor Co.) Brier Crk. (Burke Co.) Canoochee River (Hwy 192 to Lotts Crk.) Canoochee River (Lotts Crk. to Ogeechee River) Casey Canal Chattahoochee River (Helen to Lk. Lanier) (Buford Dam to Morgan Falls Dam) (Morgan Falls Dam to Peachtree Crk.) * (Peachtree Crk. to Pea Crk.) * (Pea Crk. to West Point Lk., below Franklin) * (West Point dam to I-85) (Oliver Dam to Upatoi Crk.) Chattooga River (NE Georgia, Rabun County) Chestatee River (below Tesnatee Riv.) Chickamauga Crk. (West) Cohulla Crk. (Whitfield Co.) Conasauga River (below Stateline) <18" Coosa River <20" 18 –32" (River Mile Zero to Hwy 100, Floyd Co.) ≥20" >32" <18" Coosa River <20" 18 –32" (Hwy 100 to Stateline, Floyd Co.) ≥20" >32" Coosa River (Coosa, Etowah below <20" Thompson-Weinman dam, Oostanaula) ≥20" Coosawattee River (below Carters) Etowah River (Dawson Co.) Etowah River (above Lake Allatoona) Etowah River (below Lake Allatoona dam) Flint River (Spalding/Fayette Cos.) Flint River (Meriwether/Upson/Pike Cos.) Flint River (Taylor Co.) Flint River (Macon/Dooly/Worth/Lee Cos.) <16" Flint River (Dougherty/Baker Mitchell Cos.) 16–30" >30" Gum Crk. -

Okefenokee Swamp Hydrology

OKEFENOKEE SWAMP HYDROLOGY Cynthia S. Loftin' AUTHOR: 'Graduate Research Assistant-Ph.D. Candidate, USGS-BRD Florida Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit, Department of Wildlife Ecology and Conservation, University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida 32611-0450. REFERENCE: Proceedings of the 1997 Georgia Water Resources Conference, held 20-22 March 1997, at the University of Georgia, Kathryn J. Hatcher, Editor, Institute of Ecology, The University of Georgia, Athens, Georgia. Abstract. The Okefenokee Swamp is one of North topographic relief is minimal The swamp is a bowl-like America's largest freshwater wetlands. Swamp hydrology depression in the landscape with the trend in ground surface is largely controlled by precipitation and elevation from 38.4 m at Kingfisher Landing in the evapotranspiration; regional topographic features of the Northeast to 33.0 m in the area where the Suwannee River swamp control surface water movements. Manipulations to exits the swamp in the West to 34.75 m at Ellicott's Mound the swamp topography and vegetation communities during in the Southeast near the St. Mary's River outflow. Within this century have affected water movement and variability the swamp are regional topographic highs on large sand- in parts of the swamp. Changes in swamp hydrology since based islands and lows in large prairies. The prairies also the construction of the Suwannee River Sill are generally contain local topographic highs on peat-based islands that restricted to the West Central area bounded by the Pocket, may rise a meter above the surrounding inundated peat Billy's Island, Craven's Island, Minnie's Island, and surface. -

Quick Reference Fact Sheet

Okefenokee at a Glance The Okefenokee Swamp is located in Ware, Charlton, and Clinch Counties, Georgia and Baker County, Florida. Okefenokee National Wildlife Refuge was established by Executive Order in 1936. The Okefenokee Swamp covers 438,000 acres. It is 38 miles in length at its longest point by 25 miles in width at its widest point. The swamp is approximately 700 square miles. The Okefenokee National Wildlife Refuge is over 402,000 acres. The wilderness area consists of 353,981 acres and was created by the Okefenokee Wilderness Act of 1974 which is part of the Wilderness Preservation System. Okefenokee National Wildlife Refuge is the largest National Wildlife Refuge in the eastern United States. It is administered by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service which is under the Department of the Interior. The Okefenokee Swamp is approximately 7000 years old. It is a vast peat-filled bog inside a huge, saucer-shaped depression that was once part of the ocean floor. The elevation of the swamp varies. There is a 25 foot drop from the northwest side to the southwest side. The range in elevation is from 128 feet above sea level on the northeast side to 103 feet on the southwest side. The vegetative indicator of the natural swamp line is the presence of the saw palmetto. The Suwannee River is the principle outlet of the swamp. The Suwannee flows from the west side of the swamp and empties into the Gulf of Mexico near Cedar Key, Florida. The Suwannee River is 280 miles long. A small area of the southeastern part of the swamp is drained by the St. -

DIRECT TESTIMONY of PHILIP B. BEDIENT, Ph.D., P.E

No. 142, Original In The Supreme Court of the United States STATE OF FLORIDA, Plaintiff, v. STATE OF GEORGIA, Defendant. DIRECT TESTIMONY OF PHILIP B. BEDIENT, Ph.D., P.E. October 26, 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS SUMMARY OF OPINIONS .......................................................................................................... 1 BACKGROUND AND PROFESSIONAL QUALIFICATIONS .................................................. 6 ANY CHANGE IN THE AMOUNT OR TIMING OF STATE-LINE FLOW MUST BE COORDINATED AND EXECUTED BY THE CORPS ............................................................... 7 I. The Corps Operates the Federal Reservoir Projects in the ACF Basin as a Single, Integrated System to Balance Multiple Project Purposes ................................................... 9 II. The RIOP Controls Basin-Wide Storage and Releases of Water in the Federal Reservoirs ......................................................................................................................... 17 III. The Corps Operates Its Reservoir System as a Single Unit, and Under Low-Flow Conditions Offsets Increased Flint River Flows by Decreasing Chattahoochee River Releases ................................................................................................................... 25 IV. Increases in Basin Inflow Would Not Increase State-Line Flows into Florida During Low-Flow Conditions or Drought Operations...................................................... 26 REDUCTIONS IN GEORGIA’S WATER USE WOULD NOT RESULT IN INCREASED STATE-LINE FLOWS