Transitional Justice and Education

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Elkhart Collection Lot Price Sold 1037 Hobie Catamaran $1,560.00 Sold 1149 2017 John Deere 35G Hydraulic Excavator (CHASSIS NO

Auction Results The Elkhart Collection Lot Price Sold 1037 Hobie Catamaran $1,560.00 Sold 1149 2017 John Deere 35G Hydraulic Excavator (CHASSIS NO. 1FF035GXTHK281699) $44,800.00 Sold 1150 2016 John Deere 5100 E Tractor (CHASSIS NO. 1LV5100ETGG400694) $63,840.00 Sold 1151 Forest River 6.5×12-Ft. Utility Trailer (IDENTIFICATION NO. 5NHUAS21X71032522) $2,100.00 Sold 1152 2017 Bravo 16-Ft. Enclosed Trailer (IDENTIFICATION NO. 542BE1825HB017211) $22,200.00 Sold 1153 2011 No Ramp 22-Ft. Ramp-Less Open Trailer (IDENTIFICATION NO. 1P9BF2320B1646111) $8,400.00 Sold 1154 2015 Bravo 32-Ft. Tag-Along Trailer (IDENTIFICATION NO. 542BE322XFB009266) $24,000.00 Sold 1155 2018 PJ Trailers 40-Ft. Flatbed Trailer (IDENTIFICATION NO. 4P5LY3429J3027352) $19,800.00 Sold 1156 2016 Ford F-350 Super Duty Lariat 4×4 Crew-Cab Pickup (CHASSIS NO. 1FT8W3DT2GEC49517) $64,960.00 Sold 1157 2007 Freightliner Business Class M2 Crew-Cab (CHASSIS NO. 1FVACVDJ87HY37252) $81,200.00 Sold 1158 2005 Classic Stack Trailer (IDENTIFICATION NO. 10WRT42395W040450) $51,000.00 Sold 1159 2017 United 20-Ft. Enclosed Trailer (IDENTIFICATION NO. 56JTE2028HA156609) $7,200.00 Sold 1160 1997 S&S Welding 53 Transport Trailer (IDENTIFICATION NO. 1S9E55320VG384465) $33,600.00 Sold 1161 1952 Ford 8N Tractor (CHASSIS NO. 8N454234) $29,120.00 Sold 1162 1936 Port Carling Sea Bird (HULL NO. 3962) $63,000.00 Sold 1163 1961 Hillman Minx Convertible Project (CHASSIS NO. B1021446 H LCX) $3,360.00 Sold 1164 1959 Giulietta Super Sport (FRAME NO. GTD3M 1017) $9,600.00 Sold 1165 1959 Atala 'Freccia d’Oro' (FRAME NO. S 14488) $9,000.00 Sold 1166 1945 Willys MB (CHASSIS NO. -

June WTTW & WFMT Member Magazine

Air Check Dear Member, The Guide As we approach the end of another busy fiscal year, I would like to take this opportunity to express my The Member Magazine for WTTW and WFMT heartfelt thanks to all of you, our loyal members of WTTW and WFMT, for making possible all of the quality Renée Crown Public Media Center content we produce and present, across all of our media platforms. If you happen to get an email, letter, 5400 North Saint Louis Avenue or phone call with our fiscal year end appeal, I’ll hope you’ll consider supporting this special initiative at Chicago, Illinois 60625 a very important time. Your continuing support is much appreciated. Main Switchboard This month on WTTW11 and wttw.com, you will find much that will inspire, (773) 583-5000 entertain, and educate. In case you missed our live stream on May 20, you Member and Viewer Services can watch as ten of the area’s most outstanding high school educators (and (773) 509-1111 x 6 one school principal) receive this year’s Golden Apple Awards for Excellence WFMT Radio Networks (773) 279-2000 in Teaching. Enjoy a wide variety of great music content, including a Great Chicago Production Center Performances tribute to folk legend Joan Baez for her 75th birthday; a fond (773) 583-5000 look back at The Kingston Trio with the current members of the group; a 1990 concert from the four icons who make up the country supergroup The Websites wttw.com Highwaymen; a rousing and nostalgic show by local Chicago bands of the wfmt.com 1960s and ’70s, Cornerstones of Rock, taped at WTTW’s Grainger Studio; and a unique and fun performance by The Piano Guys at Red Rocks: A Soundstage President & CEO Special Event. -

Fascicolo Ii – Iii / Maggio – Dicembre

RIVISTA DI ARTI, FILOLOGIA E STORIA NAPOLI NOBILISSIMA VOLUME LXXII DELL’INTERA COLLEZIONE SETTIMA SERIE - VOLUME I FASCICOLO II - III - MAGGIO - DICEMBRE 2015 RIVISTA DI ARTI, FILOLOGIA E STORIA NAPOLI NOBILISSIMA direttore segreteria di redazione La testata di «Napoli nobilissima» è di proprietà Pierluigi Leone de Castris Luigi Coiro della Fondazione Pagliara, articolazione Stefano De Mieri istituzionale dell'Università degli Studi Suor Orsola Benincasa di Napoli. Gli articoli pubblicati direzione Federica De Rosa su questa rivista sono stati sottoposti a valutazione Piero Craveri Gianluca Forgione rigorosamente anonima da parte di studiosi Lucio d’Alessandro Vittoria Papa Malatesta specialisti della materia indicati dalla Redazione. Ortensio Zecchino Gordon Poole Augusto Russo Un numero euro € 19,00 - doppio € 38,00 (Estero: singolo € 23,00 - doppio € 46,00) redazione Abbonamento annuale € 75,00 Giancarlo Alfano referenze fotografiche (Estero: € 103,00) Rosanna Cioffi Bari, Soprintendenza B.S.A.E. della Nicola De Blasi Puglia, pp. 30, 36 redazione Barletta, Museo Civico, pp. 106, 107 Renata De Lorenzo Università degli Studi Suor Orsola Benincasa Nicola Cleopazzo, pp. 46, 48, 49, 50, Fondazione Pagliara, via Suor Orsola 10 Arturo Fittipaldi 51 52 80131 Napoli Carlo Gasparri Fondo edifici di culto, pp. 19, 22 alto, [email protected] Gianluca Genovese 24, 108 Riccardo Naldi Luigi Maglio, p. 65 destra amministrazione Francesco Liuzzi, pp. pp. 80, 82, 83, 84, Giulio Pane prismi editrice politecnica napoli srl 85, 86, 87, 88, 89 via Argine 1150, 80147 Napoli Valerio Petrarca Gattatico (RE), Istituto Alcide Cervi, Mariantonietta Picone Biblioteca Archivio Emilio Sereni, pp. Federico Rausa 120, 121, 122, 123, 124, 125 Nunzio Ruggiero Lucera, Museo Diocesano, p. -

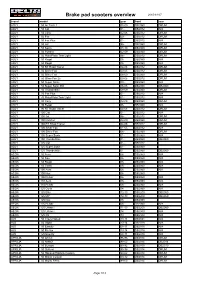

Brake Pad Scooters Overview

Brake pad scooters overview 2015-01-07 brand model year front rear ADLY 50 Air Tech 1 08-09 DB2060 DRUM ADLY 50 Cat 01- DB2012 N/A ADLY 50 Cosy 02-06 DB2012 DRUM ADLY 50 Fox 00- DB2012 DRUM ADLY 50 Fox Plus 01- DB2012 N/A ADLY 50 Jet 96- DB2060 DRUM ADLY 50 Noble 08-10 DB2060 DRUM ADLY 50 Panther 02-09 DB2060 DRUM ADLY 50 Pista/Pista Twin Light 96- DB2012 DRUM ADLY 50 Regal 06 DB2060 N/A ADLY 50 Regal 06 DB2060 N/A ADLY 50 RT Road Tracer 04-06 DB2012 DRUM ADLY 50 Silver Fox 00-05 DB2012 DRUM ADLY 50 Silver Fox 06-09 DB2060 DRUM ADLY 50 Silver Fox 25 00-05 DB2012 DRUM ADLY 50 Super Sonic 00 - DB2060 N/A ADLY 50 Super Sonic RS 06-08 DB2060 DB2060 ADLY 50 Thunderbike 08-09 DB2060 DRUM ADLY 70 Fox Plus 01- DB2012 N/A ADLY 70 Pista/Pista Twin Light 01- DB2012 N/A ADLY 80 Cosy 02-06 DB2060 DRUM ADLY 90 Regal 06 DB2060 N/A ADLY 90 RT Road Tracer 04-06 DB2012 DRUM ADLY 100 Cat 01- DB2012 N/A ADLY 100 Jet 96- DB2012 DRUM ADLY 100 Panther 02-09 DB2060 DRUM ADLY 100 RT Road Tracer 04-06 DB2012 DRUM ADLY 100 Silver Fox 01-05 DB2012 N/A ADLY 100 Silver Fox 06- DB2060 DRUM ADLY 100 Super Sonic 01- DB2060 N/A ADLY 100 Thunderbike 01- DB2060 DB2060 ADLY 125 Cat 01- DB2012 ADLY 125 Super Sonic 01- DB2060 ADLY 125 Thunderbike 01- DB2060 DB2060 AEON 50 Aero 06 DB2060 N/A AEON 50 Nox 06 DB2060 N/A AEON 50 Regal 06 DB2060 N/A AEON 50 Torch 06- DB2060 N/A AEON 100 Aero 06 DB2060 N/A AEON 100 Nox 06 DB2060 AEON 100 Pulsar 06 DB2060 N/A AEON 110 Aero 06- DB2060 N/A AEON 110 Pulsar 06- DB2060 N/A AEON 125 Co-In 14 DB2060 N/A AEON 125 Elite 12-13 DB2200 DB2050 -

Unusual Approaches to Teaching the Holocaust. Jan Láníček, Andy

Láníček, J., Pearce, A., Raffaele, D., Rathbone, K. & Westermann, E. “Unusual Approaches to Teaching the Holocaust”. Australian Journal of Jewish Studies XXXIII (2020): 80-117 Unusual Approaches to Teaching the Holocaust. Jan Láníček, Andy Pearce, Danielle Raffaele, Keith Rathbone & Edward Westermann Introduction (Láníček) Holocaust pedagogy keeps evolving. Educators all over the world develop new lecture materials and in-class exercises, select new resources to engage emerging generations of students with the topic, and design assessment tasks that test diverse skills, but also challenge students to re-think perhaps familiar topics. In an era when students can easily access a large volume of resources online – often of problematic quality, and when the film industry keeps producing Holocaust blockbusters in large numbers – we as educators need to be selective in our decisions about the material we use in face-to-face or virtual classrooms. Apart from technological advances in the last decades which facilitate but also complicate our efforts, we are now quickly approaching the post-witness era, the time when we will not be able to rely on those who “were there”. This major milestone carries various challenges that we need to consider when preparing our curriculum in the following years. But we have reason to be optimistic. Student interest in Holocaust courses remains high, and also the general public and governmental agencies recognize and support the need for education in the history of genocides. If we focus on Australia alone, a new Holocaust museum was just open in Adelaide, South Australia, and there are progressing plans to open Holocaust museums in Brisbane and Perth, the capitals of Queensland and Western Australia. -

Motorcycle Parts 2010 Filtri Aria Air Filters

FILTRI ARIA AIR FILTERS 10 060 0010 10 060 0020 10 060 0030 100600010 100600020 100600030 APRILIA APRILIA APRILIA 10 060 0040 10 060 0050 10 060 0060 100600040 100600050 100600060 APRILIA ATALA BENELLI - BETA - MALAGUTI - MBK YAMAHA 10 060 0080 10 060 0090 10 060 0110 100600080 100600090 100600110 GILERA - PIAGGIO GILERA - PIAGGIO GILERA - PIAGGIO 10 060 0120 10 060 0130 10 060 0140 100600120 100600130 100600140 APRILIA - GILERA -ITALJET - PIAGGIO PEUGEOT HONDA 10 060 0170 10 060 0200 10 060 0210 100600170 100600200 100600210 HONDA HONDA HONDA 77 WWW.RMS.IT MOTORCYCLE PARTS 2010 FILTRI ARIA AIR FILTERS 10 060 0220 10 060 0230 10 060 0240 100600220 100600230 100600240 HONDA HONDA ITALJET 10 060 0260 10 060 0270 10 060 0280 100600260 100600270 100600280 KYMCO KYMCO KYMCO 10 060 0290 10 060 0300 10 060 0310 100600290 100600300 100600310 MALAGUTI MALAGUTI MBK - YAMAHA 10 060 0320 10 060 0330 10 060 0340 100600320 100600330 100600340 MBK MBK - YAMAHA - MALAGUTI MBK 10 060 0350 10 060 0360 10 060 0370 100600350 100600360 100600370 MBK - YAMAHA PEUGEOT PEUGEOT 78 MOTORCYCLE PARTS 2010 WWW.RMS.IT FILTRI ARIA AIR FILTERS 10 060 0380 10 060 0390 10 060 0400 100600380 100600390 100600400 PEUGEOT PEUGEOT PIAGGIO 10 060 0410 10 060 0420 10 060 0430 100600410 100600420 100600430 PIAGGIO BENELLI - ITALJET - PIAGGIO GILERA - PIAGGIO 10 060 0440 10 060 0460 10 060 0470 100600440 100600460 100600470 PIAGGIO PIAGGIO PIAGGIO 10 060 0480 10 060 0500 10 060 0510 100600480 100600500 100600510 PIAGGIO PIAGGIO PEUGEOT 50 10 060 0520 10 060 0530 10 060 0600 100600520 -

Ford Foundation Annual Report 2000 Ford Foundation Annual Report 2000 October 1, 1999 to September 30, 2000

Ford Foundation Annual Report 2000 Ford Foundation Annual Report 2000 October 1, 1999 to September 30, 2000 Ford Foundation Offices Inside front cover 1 Mission Statement 3 President’s Message 14 Board of Trustees 14 Officers 15 Committees of the Board 16 Staff 20 Program Approvals 21 Asset Building and Community Development 43 Peace and Social Justice 59 Education, Media, Arts and Culture 77 Grants and Projects, Fiscal Year 2000 Asset Building and Community Development Economic Development 78 Community and Resource Development 85 Human Development and Reproductive Health 97 Program-Related Investments 107 Peace and Social Justice Human Rights and International Cooperation 108 Governance and Civil Society 124 Education, Media, Arts and Culture Education, Knowledge and Religion 138 Media, Arts and Culture 147 Foundationwide Actions 155 Good Neighbor Grants 156 157 Financial Review 173 Index Communications Back cover flap Guidelines for Grant Seekers Inside back cover flap Library of Congress Card Number 52-43167 ISSN: 0071-7274 April 2001 Ford Foundation Offices • MOSCOW { NEW YORK BEIJING • NEW DELHI • • MEXICO CITY • CAIRO • HANOI • MANILA • LAGOS • NAIROBI • JAKARTA RIODEJANEIRO • • WINDHOEK • JOHANNESBURG SANTIAGO • United States Africa and Middle East West Africa The Philippines Andean Region Makati Central Post Office and Southern Cone Headquarters Eastern Africa Nigeria P.O. Box 1936 320 East 43rd Street P.O. Box 2368 Chile Kenya 1259 Makati City New York, New York Lagos, Nigeria Avenida Ricardo Lyon 806 P.O. Box 41081 The Philippines 10017 Providencia Nairobi, Republic of Kenya Asia Vietnam Santiago 6650429, Chile 340 Ba Trieu Street Middle East and North Africa China Hanoi, Socialist Republic International Club Office Building Russia Egypt of Vietnam Suite 501 Tverskaya Ulitsa 16/2 P.O. -

Flyer IHRA.Indd

International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance (Ed.) Killing Sites Research and Remembrance Co-Ed.: Steering Committee: Dr. Thomas Lutz (Topography of Terror Foundation, Berlin), Dr. David Silberklang (Yad Vashem, Jerusalem), Dr. Piotr Trojański (Institute of History, Pedagogical University of Krakow), Dr. Juliane Wetzel (Center for Research on Antisemitism, TU Berlin), Dr. Miriam Bistrovic (Project Coordinator) IHRA series, vol. 1 More than 2,000,000 Jews were killed by shooting during the Holocaust Metropol Verlag at several thousand mass killing sites across Europe. e International März 2015 Holocaust Remembrance Alliance (IHRA) aims to raise awareness of ISBN: ---- this centrally important aspect of the Holocaust by bringing together Seiten · ,– Euro organizations and individuals dealing with the subject. is publication is the rst relatively comprehensive and up-to-date anthology on the topic that re ects both the research and the eldwork on the Killing Sites. ........................................................................................................................................ INTRODUCTORY LECTURES REGIONAL PERSPECTIVES David Silberklang: Killing Sites – Research and Remembrance Jacek Waligóra: “Periphery of Remembrance”. Dobromil and Lacko Introduction to the Conference and IHRA Perspective Alti Rodal: e Ukrainian Jewish Encounter’s Position and Dieter Pohl: Historiography and Nazi Killing Sites Aims in Relation to Killing Sites in the Territory of Ukraine Andrej Angrick: Operation 1005: e Nazi Regime’s Meylakh -

Narrow but Endlessly Deep: the Struggle for Memorialisation in Chile Since the Transition to Democracy

NARROW BUT ENDLESSLY DEEP THE STRUGGLE FOR MEMORIALISATION IN CHILE SINCE THE TRANSITION TO DEMOCRACY NARROW BUT ENDLESSLY DEEP THE STRUGGLE FOR MEMORIALISATION IN CHILE SINCE THE TRANSITION TO DEMOCRACY PETER READ & MARIVIC WYNDHAM Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at press.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Creator: Read, Peter, 1945- author. Title: Narrow but endlessly deep : the struggle for memorialisation in Chile since the transition to democracy / Peter Read ; Marivic Wyndham. ISBN: 9781760460211 (paperback) 9781760460228 (ebook) Subjects: Memorialization--Chile. Collective memory--Chile. Chile--Politics and government--1973-1988. Chile--Politics and government--1988- Chile--History--1988- Other Creators/Contributors: Wyndham, Marivic, author. Dewey Number: 983.066 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU Press. Cover photograph: The alarm clock, smashed at 14 minutes to 11, symbolises the anguish felt by Michele Drouilly Yurich over the unresolved disappearance of her sister Jacqueline in 1974. This edition © 2016 ANU Press I don’t care for adulation or so that strangers may weep. I sing for a far strip of country narrow but endlessly deep. No las lisonjas fugaces ni las famas extranjeras sino el canto de una lonja hasta el fondo de la tierra.1 1 Victor Jara, ‘Manifiesto’, tr. Bruce Springsteen,The Nation, 2013. -

Jerusalemhem Volume 91, February 2020

Yad VaJerusalemhem Volume 91, February 2020 “Remembering the Holocaust, Fighting Antisemitism” The Fifth World Holocaust Forum at Yad Vashem (pp. 2-7) Yad VaJerusalemhem Volume 91, Adar 5781, February 2020 “Remembering the Holocaust, Published by: Fighting Antisemitism” ■ Contents Chairman of the Council: Rabbi Israel Meir Lau International Holocaust Remembrance Day ■ 2-12 Chancellor of the Council: Dr. Moshe Kantor “Remembering the Holocaust, Vice Chairman of the Council: Dr. Yitzhak Arad Fighting Antisemitism” ■ 2-7 Chairman of the Directorate: Avner Shalev The Fifth World Holocaust Forum at Yad Vashem Director General: Dorit Novak Tackling Antisemitism Through Holocaust Head of the International Institute for Holocaust ■ 8-9 Research and Incumbent, John Najmann Chair Education for Holocaust Studies: Prof. Dan Michman Survivors: Chief Historian: Prof. Dina Porat Faces of Life After the Holocaust ■ 10-11 Academic Advisor: Joining with Facebook to Remember Prof. Yehuda Bauer Holocaust Victims ■ 12 Members of the Yad Vashem Directorate: ■ 13 Shmuel Aboav, Yossi Ahimeir, Daniel Atar, Treasures from the Collections Dr. David Breakstone, Abraham Duvdevani, Love Letter from Auschwitz ■ 14-15 Erez Eshel, Prof. Boleslaw (Bolek) Goldman, Moshe Ha-Elion, Adv. Shlomit Kasirer, Education ■ 16-17 Yehiel Leket, Adv. Tamar Peled Amir, Graduate Spotlight ■ 16-17 Avner Shalev, Baruch Shub, Dalit Stauber, Dr. Zehava Tanne, Dr. Laurence Weinbaum, Tamara Vershitskaya, Belarus Adv. Shoshana Weinshall, Dudi Zilbershlag New Online Course: Chosen Issues in Holocaust History ■ 17 THE MAGAZINE Online Exhibition: Editor-in-Chief: Iris Rosenberg Children in the Holocaust ■ 18-19 Managing Editor: Leah Goldstein Editorial Board: Research ■ 20-23 Simmy Allen The Holocaust in the Soviet Union Tal Ben-Ezra ■ 20-21 Deborah Berman in Real Time Marisa Fine International Book Prize Winners 2019 ■ 21 Dana Porath Lilach Tamir-Itach Yad Vashem Studies: The Cutting Edge of Dana Weiler-Polak Holocaust Research ■ 22-23 ■ Susan Weisberg At the invitation of the President of the Fellows Corner: Dr. -

Children's Play in the Shadow of War •

Children’s Play in the Shadow of War • Daniel Feldman The author demonstrates that war places children’s play under acute stress but does not eliminate it. He argues that the persistence of children’s play and games during periods of armed conflict reflects the significance of play as a key mode for children to cope with conditions of war. Episodes of children’s play drawn from the recent Syrian Civil War illustrate the precariousness and importance of children’s play and games during contemporary armed conflict and focus attention on children’s play as a disregarded casualty of war. The article compares the state of underground children’s play in con- temporary Syria with the record of clandestine games played by children in the Holocaust to substantiate its claim that children adapt their play to concretize and comprehend traumatic wartime experience. The article posits that play is both a target of war and a means of therapeutically contending with mass violence. Key words: play and trauma; play therapy; Syrian Civil War; the Holocaust; underground play; war play Children’s play typically becomes one of the first targets of armed conflict. Even before hostilities reach a fever pitch and mortality figures soar to appalling heights, families rush children from vulnerable play spaces, curtail their outdoor games, and interrupt everyday play in many other ways because children’s basic safety, obviously, takes precedence over recreational activity. Characterized by the looming threat of physical danger and pernicious scarcity, war puts both the free play and structured games of childhood under intense strain. -

Allegato A) – ELENCO BICICLETTE

Allegato A) – ELENCO BICICLETTE DATA MARCA M/F COLORE CARATTERISTICHE PROTOCOLLO RITROVAMENTO 1 ATALA M GRIGIO CHIARO P.P. POST E SELLA NERA ROTTA 281/17 28/03/2017 2 ATALA REPLAY 21 SPEED M/F BIANCO/VERDE/GIALLINO CAMBIO SHIMANO 607/17 08/08/2017 3 AVENUE F GRIGIO/NERO 802/17 20/11/2017 4 ATALA M GRIGIO VELOCE LOG. 856/17 30/11/2017 5 ATALA M BLU VELOCE LOG. 857/17 30/11/2017 6 ATALA F ROSSO VELOCE LOG. 872/17 30/11/2017 7 ATALA F ROSSO VELOCE LOG. 876/17 30/11/2017 8 ANGEL F NERO VELOCE LOG. 885/17 30/12/2017 9 ASTER M MULTICOLOR RUOTE RAIDER 161/18 05/03/2018 10 ATALA F BIANCO/VIOLA MOD. BRIDGE 164/18 05/03/2018 11 ATALA F NERO 451/18 05/06/2018 12 AERELLI F BIANCO/ROSSA 717/18 28/08/2018 13 ATALA UP OS-2100 M ROSA/VIOLA 732/18 28/08/2018 14 ALPINA F MARRONE BRUNITO MOD. HOLLAND CON 2 P.P. 756/18 24/09/2018 15 ATALA M/F VIOLA/ARANCIONE 1088/18 12/12/2018 16 ATALA M/F ROSSO/NERO CON TACHIMETRO 81/19 25/01/2019 17 ATALA M/F BIANCO/ROSSO 101/19 25/01/2019 18 BERGA M ARAGOSTA SELLA NERA, P.P. POST. AZZURRO 274/17 28/03/2017 19 BERGA (LELLA) MOD. F GRIGIO P.P. ANT. E P.P. POST. 280/17 28/03/2017 GRAZIELLA 20 BIANCHI M ROSSO MONO CAMBIO, SELLA NERA, P.P.