Anti-Anti-Catalanism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nsfer // 2011 II

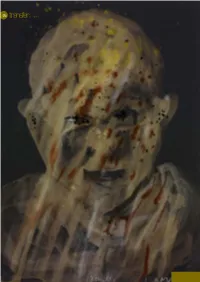

06 transfer // 2011 II MartÍ PEraN & GErarD VIlar Art and Aesthetics A conversation on Catalan aesthetic thought The history of aesthetic thought is one of the most glaring gaps in Catalan historiography. The fact that there is no strong tradition in this field makes things even harder. However, although our contribution clearly derives from other contexts, this does not stop one getting an idea of the kind of literature that has accompanied modern and contemporary artistic output. A great deal of data needs to be weighed in pursuing the subject. The following conversation is simply an informal way of raising various themes, which may be explored or altered later on. ➔ Martí Peran: Gerard, I suggest we conduct this interview-cum-conversation in a very informal way, without following any kind of order so that themes can be discussed as they crop up. With this in mind, before mentioning names and local traditions, perhaps it would be worth commenting on where aesthetic reflection is currently to be found. I believe that in addition to conventional essays (published books, etc.), contemporary aesthetic thought is waxing in fields such as artistic and literary criticism and indeed in all literatures. Of course, this has a lot to do with the way Mamadou, Miquel Barceló (nov 2009) Mixed media on cardboard, 65 x 50 cm 112/113 II Art AND AESthETICS. A CONVERSatION ON CatalaN AESthETIC thOUght modern heterodoxy has displaced culture from centre stage. In any case, I think it important to ask to what extent aesthetic thought should respect historic patterns. - Gerard Vilar: It is true that many new forums for aesthetic discourse have sprung up over the last twenty years, while some of the old ones have been abandoned. -

Picasso Versus Rusiñol

Picasso versus Rusiñol The essential asset of the Museu Picasso in Barcelona is its collection, most of which was donated to the people of Barcelona by the artist himself and those closest to him. This is the museum’s reason for existing and the legacy that we must promote and make accessible to the public. The exhibition Picasso versus Rusiñol is a further excellent example of the museum’s established way of working to reveal new sources and references in Picasso’s oeuvre. At the same time, the exhibition offers a special added value in the profound and rigorous research that this project means for the Barcelona collection. The exhibition sheds a wholly new light on the relationship between Picasso and Rusiñol, through, among other resources, a wealth of small drawings from the museum’s collection that provide fundamental insight into the visual and iconographic dialogues between the work of the two artists. The creation of new perspectives on the collection is one of the keys to sustaining the Museu Picasso in Barcelona as a living institution that continues to arouse the interest of its visitors. Jordi Hereu Mayor of Barcelona 330 The project Picasso versus Rusiñol takes a fresh look at the relationship between these two artists. This is the exhibition’s principal merit: a new approach, with a broad range of input, to a theme that has been the subject of much study and about which so much has already been written. Based on rigorous research over a period of more than two years, this exhibition reviews in depth Picasso’s relationship — first admiring and later surpassing him — with the leading figure in Barcelona’s art scene in the early twentieth century, namely Santiago Rusiñol. -

Contemporary Catalan Theatre: an Introduction

CONTEMPORARY CATALAN THEATRE AN INTRODUCTION Edited by David George & John London 1996 THE ANGLO-CATALAN SOCIETY THE ANGLO-CATALAN SOCIETY OCCASIONAL PUBLICATIONS No. 1 Salvador Giner. The Social Structure of Catalonia (1980, reprinted 1984) No. 2 Joan Salvat-Papasseit. Selected Poems (1982) No. 3 David Mackay. Modern Architecture in Barcelona (1985) No. 4 Forty Modern Catalan Poems (Homage to Joan Gili) (1987) No. 5 E. Trenc Ballester & Alan Yates. Alexandre de Riquer (1988) No. 6 Salvador Espriu. Primera història d'Esther with English version by Philip Polack and Introduction by Antoni Turull (1989) No. 7 Jude Webber & Miquel Strubell i Trueta. The Catalan Language: Progress Towards Normalisation (1991) No. 8 Ausiàs March: A Key Anthology. Edited and translated by Robert Archer (1992) No. 9 Contemporary Catalan Theatre: An Introduction. Edited by David George í John London (1996) © for this edition by David George & John London © for the individual essays by the authors Produced and typeset by Interleaf Productions Limited, Sheffield Printed by The Cromwell Press, Melksham, Wiltshire Cover design by Joan Gili ISBN 0-9507137-8-3 Contents Acknowledgements 7 Preface 9 List of Illustrations 10 Introduction 11 Chapter 1 Catalan Theatrical Life: 1939-1993 Enric Gallén 19 The Agrupació Dramàtica de Barcelona 22 The Escola d'Art Dramàtic Adrià Gual and Committed Theatre 24 The Final Years of the Franco Regime 27 The Emergence of Resident Companies after the End of Francoism . .29 Success Stories of the 1980s 35 The Future 37 Chapter 2 Drama -

Terrorism Revisited 2

1. Some background notes Terrorism Revisited I shall start with a bang. On No- Modernisme, Art, and Anarchy vember 7, 1893, opening night of the in the City of Bombs season at the Barcelona opera house, the Liceu,1 two Orsini bombs were Eduardo Ledesma tossed into the audience. The carnage was considerable, some twenty people were killed, many injured. It was the work of anarchist Santiago Salvador, in retaliation for the execution of Paulí Pallás, another anarchist who earlier that year had unsuccessfully tried to assassinate the Madrid appointed Cap- tain General of Catalonia, Martínez Campos. Pallás’ terrorist act was viewed with admiration by some mem- bers of the working class, perhaps even by some sectors of the bourgeoisie, re- sentful of Madrid’s rule, but the explo- sion at the Liceu deeply shocked the Eduardo Ledesma is a graduate student in upper echelons of Barcelona society, the Spanish and Portuguese at Harvard. His “bones families” or good families. The academic interests include 20th and 21st Liceu bombing became a symbol of so- century Ibero-American literature (in cial unrest, exposing the fissures of a Spanish, Catalan, and Portuguese) as well polarized society. What followed— as film and new media studies. He is cur- justified in the eyes of many—was a pe- rently working on his dissertation, which riod of police repression, of suspect explores the intersections between word round-ups, military trials and summary and image in experimental poetry, from executions, directed (mostly) at the the avant-gardes to the digital age. Edu- working class quarters of Barcelona. -

The Gran Teatre Del Liceu in Catalan Culture

The Gran Teatre del Liceu in Catalan Culture: History, Representation and Myth Charlie Allwood Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy 1 This thesis examines the position of Barcelona’s Gran Teatre del Liceu within Barcelona’s cultural lanscapeas a means of exploring its modern-day role as one of Europe’s most important opera houses. Other studies of the Liceu have provided extensive historical narratives, but have rarely considered any kind of sociological or cultural theory when analysing the theatre’s role in the city. Chapter 1 explores the Liceu in Spanish and Catalan literature and dramaturgy and questions its role as a representative of upper-class Barcelona culture, and the changes this role has undergone over the course of Spain’s transition to democracy. The Liceu’s location in the adjacent Raval district is examined in Chapter 2: the area has undergone considerable physical and demographic changes over the last decades, and the opera house’s relationship to this area and the larger Barcelona context is discussed in some detail. The third chapter contextualises the Liceu within the wider Catalan cultural panorama and examines the impact of the recession in Spain, which has greatly affected cultural spending, and consequently the theatre’s programme. This problem has been aggravated by an awkward, opaque system of management; the thesis provides examples and analysis of the difficulties the theatre experienced between 2010 and 2013. The final chapter seeks to underline the efforts of the artistic direction to make the Liceu a referent of modern European operatic productions, with three case studies of stagings that represent modern interpretations of opera by contemporary Catalan directors. -

Catalogue of Titles in Catalan

- Setmana del Llibre en Català - September 2017 Catalogue of titles in Catalan Sandra Bruna Agencia Literaria Gal·la Placídia 2, 5-2 Barcelona 08006 T +34 93 217 74 06 [email protected] Fiction for Adults La hija del capitán Groc (Captain Groc´s Daughter) The Catalan Braveheart. A story about the power of love and the ideals of a man. Tomás Penarrocha, El Groc, is a fascinating character and the soul of the novel. A bandit for ones and a fighter for others, he is a popular hero, the romantic defender of a lost cause in a realistic and mythical micro geography. He leads a novel in which women have a significant role, such as the other main character, his teenage daughter, who unconditionally supports and admires her father and his ideals; and his loving wife, who might not be as brave, but is certainly cautious. With oral tradition and a hint of Robin Fiction /Historical novel Hood, La Hija del Capitán Groc is the Catalan Braveheart; Original title: La filla del capità Groc a story about fight and love, jealousy and betrayal, Original language: Catalan friendship and sacrifice and, above all, freedom beyond 420 pages Published in 2016 reason. Material available: Spanish, Catalan and French pdf “Amela is a magnificent creator, and keeps the reader on the edge of RIGHTS SOLD their seat, amazed at life and death with these page-turning events.” Catalan (Planeta, Grupo Planeta) —La Vanguardia Spanish (Planeta, Grupo Planeta) French (Belfond) “An intense story full of fascinating characters such as Groc himself and his daughter Manuela, a determined young woman who follows her father’s figure and who will steal your heart.”—Sílvia Cantos “El Groc (…) is both a fascinating and picturesque character who perfectly incarnates the romantic hero that we are all eager to read and meet.” —Miss Cultura Key selling points Winner of the Ramon Llull Award, the most prestigious prize in the Catalan Language. -

Catalan Literature and Translation in a Globalized World

CATALAN LITERATURE AND TRANSLATION IN A GLOBALIZED WORLD Carme Arenas and Simona Skrabec Translated by Sarah Yandell PRESENTATION The latest edition of Nabí by Josep Carner enables one to take a detailed look at the creative process of the three versions of the text written by the poet over a two-year period. The first version was for an edition by the Institution of Catalan Letters (Institució de les Lletres Catalanes or ILC), whose activities were ceased when Franco’s troops entered Barcelona in January 1939. The second was the translation of the poem into Spanish undertaken by Carner for publi- cation in Mexico in 1940, and the third, definitive version came after a final revision and was published in Buenos Aires in 1941. The poet’s dedication to translation and to poetic creation during the first years of his exile is touching, but still more poignant is the fact that, thanks to his work, we are able to read, in detail, about how languages mutually nourish one another. Indeed, in the definitive version of a work that represents one of the high points of Catalan poetry, clear traces of the Spanish version can be found: some of the most perennial Catalan verses were ‘given’ to the poet during his work on the Spanish translation. This extreme example has been used to begin this report on translation in Catalonia, with the affirmation that translation is the touchstone in any living literature. Translation is not a process that comes after literary creation, limit- ed to communicating what was created in a closed literary context in anoth- er language. -

EDITORIAL an International Showcase

CATALAN WRITING 2 EDITORIAL An international showcase EDITORIAL for catalan literature ACTIONS & VOICES The appearance of the second issue of INTERVIEW Catalan Writing in this exciting phase of ON POETRY its existence—coinciding with the 2007 WORK IN PROGRESS Frankfurt Book Fair at which Catalan PUBLISHING NEWS culture was guest of honour—is a good ON STAGE opportunity to encourage readers to ON LINE discover more about our literature and explore it deeper. Catalan literature WHO’S WHO and the great variety of works written in the Catalan language in its different territories – from Barcelona to Mallorca and from Perpignan to Andorra and Valencia – has a remarkably rich history, Chief editor: Dolors Oller Editor: Carme Arenas and has contributed a considerable Editorial Staff: number of men and women writers to Josep Bargalló Emili Manzano the body of world literature from its Ramon Pla Arxer beginnings to the present day. Starting Jaume Subirana with Ramon Llull, the first person to Il·lustration: Ramon Enrich use a Romance language for literary creation and ideas, and continuing to today’s writers Coordination and documentation: like Quim Monzó, Baltasar Porcel, Francesc Mira, Carme Riera and Pere Gimferrer—the five Glòria Oller Translation: Discobole writers of diverse styles and genres who presented our wide-ranging literary programme at Proof-reading: Zachary Shtogren Design: Azuanco & Comadira the Frankfurt Book Fair—Catalan literature has had a role in shaping European history. The Printed by: early classics laid a foundation with the medieval novel Tirant lo Blanc and works by the poet Edited and distributed by: Ausiàs March. -

Auca Del Born SEPTEMBER 2013

Principal Activities Tricentenari BCN SEPTEMBER 2013 Auca del Born PERFORMING ARTS The inaugural event of the Tercentenary BCN and the Born Cultural Centre, the new site housed in the Born Market, is a tribute to the citizens who lived and fought in La Ribera neighbourhood in 1714. Written and directed by Jordi Casanovas, an outstanding talent on the Catalan theatre scene today, Auca del Born is a dynamic, moving show that comprises a series of short, fast, simultaneous scenes that, almost like a comic book story, illustrate life in the Born neighbourhood during the year 1700. The show features a total of 48 brief scenes, performed by some 30 actors positioned at different points on the archaeological site and along the gangways around it. The leading characters in this piece, a young couple, will introduce spectators to family life in the neighbourhood in the years leading up to 1714, describing their trades as well as their love of celebration and games. They will present a people who are open, optimistic, enjoy life and never hesitate to defend freedom. AUCA DEL BORN. Written and directed by: Jordi Casanovas. Production: Bitò Produccions. September 12, 13, 14, 15, 19, 26, 27 and 28: 9 pm September 20, 21, 22, 23 and 24: 9 pm and 10.30 pm Price: €2. Limited capacity. Accessible to people with disabilities. You can now buy tickets for Auca del Born through this website and at the Tiquet Rambles office in Palau de la Virreina (La Rambla 99, Monday to Sunday, from 10 am to 8.30 pm) as well as, from 12 September, the ticket office of the Born Cultural Centre. -

Rusiñol's Modernist Jottings Along Life's Way and García Lorca's Impresiones Y Paisajes

VOLUME 2, NUMBER 1 SUMMER 2005 Rusiñol’s Modernist Jottings along Life’s Way and García Lorca’s Impresiones y paisajes Nelson Orringer García Lorca’s earliest writings (1917–18) reveal his initial identification with Hispanic modernism, which first came into being in Catalonia.1 Catalan modernistes had introduced the word “modernist” in its contemporary acceptation into the languages of the Iberian Peninsula. L’Avenç, a Barcelonese journal and publishing house, first employed the adjective modernista in the sense of an attitude of approval towards innovation in all spheres of culture. One leader of L’Avenç, the Barcelonese essayist, novelist, poet, playwright, and painter Santiago Rusiñol y Prats (1861–1931), achieved popularity in Catalonia for his poetic essays on travel, on life in general viewed as a journey, and on landscapes in particular (Ginsberg 1445). His collection of artistic essays Fulls de la vida (“Life’s Pages,” 1898) received a poetic, laudatory review from Unamuno (1296–98)—a figure much admired by Lorca (3: 964)—in the Madrid review La Época in March 1899. Rusiñol’s first essay collection in Catalan, Anant pel món (“Rambling through the World,” 1896), along with Fulls de la vida, went through many editions.2 The present study compares these jottings along life’s way, added to a third collection of travel essays titled Impresions i paisatges (1880–82), with García Lorca’s earliest published book, Impresiones y paisajes (1918), to help define his adolescent modernism. First, we examine Rusiñol’s mature notion of modernism while citing notable examples from his three essay collections already mentioned. -

Terrorism Revisited May 2011

1. Some background notes Terrorism Revisited Let’s start with a bang. On Novem- Modernisme, Art, and Anarchy ber 7, 1893, opening night of the season in the City of Bombs at the Barcelona opera house, the Liceu,1 two Orsini bombs were tossed Eduardo Ledesma into the audience. The carnage was considerable, some twenty people were killed, many injured. It was the work of anarchist Santiago Salvador, in retalia- tion for the execution of Paulí Pallás, another anarchist who earlier that year had unsuccessfully tried to assassinate the Madrid appointed Captain General of Catalonia, Martínez Campos. Pallás’ terrorist act was viewed with admira- tion by some members of the working class, perhaps even by some sectors of the bourgeoisie, resentful of Madrid’s rule, but the explosion at the Liceu deeply shocked the upper echelons of Eduardo Ledesma is a graduate student in Barcelona society, the “bones families” Spanish and Portuguese at Harvard. His or good families. The Liceu bombing be- academic interests include 20th and 21st came a symbol of social unrest, expos- century Ibero-American literature (in ing the fissures of a polarized society. Spanish, Catalan, and Portuguese) as well What followed—justified in the eyes of as film and new media studies. He is cur- many—was a period of police repres- rently working on his dissertation, which sion, of suspect round-ups, military tri- explores the intersections between word als and summary executions, directed and image in experimental poetry, from (mostly) at the working class quarters the avant-gardes to the digital age. Edu- of Barcelona. -

Santiago Rusiñol the Modern Artist and Modernist Barcelona

97 II Pilar Vélez Santiago Rusiñol The modern artist and Modernist Barcelona Rusiñol was born in 1861, in Carrer de la Princesa number 37, into a family of industrialists with a cotton factory in Manlleu, the office of which was on the mezzanine floor of the building where they lived. He died in 1931 in Aranjuez, while painting what was to be his last garden. In other words, he lived seventy years that coincided with one of the most agitated stages of the socio-political, economic and cultural life of Barcelona. He was a leading figure in the the beginnings of democratisation, with transformations the city underwent, the rise of the liberal professions and new lived through them and, more important, figures like the intellectual and the artist. contributed notably towards them, It was also when the phenomenon of the especially during one particular progressive construction of the Catalan stage of his life. national identity appeared, along with In 1861, Barcelona had some 240,000 the need to confront Spain, a decrepit, inhabitants and, with the centralist broken-backed, ruined Spanish state that political system that prevailed in Spain had lost its last American colonies, and at the time, it had been relegated to the was cut off from Europe. status of provincial city. By 1931 it had reached the figure of a million inhabitants A single-minded artist’s vocation and had consolidated as a modern city. From his childhood, Rusiñol had wanted To be brief, this transformation was to be a painter and defined himself as characterised above all by sweeping a painter.