University of Szeged Faculty of Arts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hoi Polloi, 1989

SHELVED IN BOUND PERIODICALS ------------ -----· ---- hoi polloi* Staff Stacey Alexander Terry Hulsey Angie Roberts Faculty Advisors Thomas J. Sauret William Bradley Strickland V.l Il l •HOY-po-LOY: noun. 1. The common masses; the man in the street; the average person; the herd. 2. A literary publication of Gainesville College, comprised of nonfiction essays. Copy1ight 1989 by the Humanities Division of Gnincsvillc College. At> 2 \ t:...i 1 This publication consists of essays written by 'w'lq9~ e, ,f Gainesville College students. I hope that this slim vol ume of student writing helps illustrate what is right with Gainesville College. It clearly reflects the fact that the hoi polloi college attracts insightful, talented, a~ intelluctually curious students who take the time and effort to do more than what is required of them in a classroom. Only three of these essays were written as asignments for a writing course . This first Hoi Polloi attests that there is a place Table ofContents on campus for students who want more than a "drive through" education. All except one of these essays went through revisions and have been changed significantly by Wonderful Male Species.. ............................................. 3 the authors. These writers did not work for a grade; they By Diane Wall worked at the writing because they truly had something to say and they wanted to say it well. The Youth Syndrome.. ................................................5 By Stacey Alexander Hoi Polloi is a collection of the best non-fiction essays written at the College over the past year. The three Autumn............ ............................................................!! winners of the Gainesville College Writing Contest are By Teresa Smith included here. -

1986 April Engineers News

ANALYSIS OF STATEWIDE PROPOSITIONS * OF Op Hwy. 101/380 .f ... I../....59-0"....f . ' 4+ Interchange :·4:.4 M 1 Z. Proceeds on Schedule - See photo :-,?34.-.. *44 4,3 Story Pg. 8 -~ .: 042·1{41 1 - VOL. 38, NO. 4 SAN FRANCISCO, CA APRIL 1986 Members ratify Master Agreement t 'Landmark' contract provides increase, fights open shop 1 Managing Editor A landmark three-year Master Con- struction Agreement that Business Ma- r 8 4.: =Br .. #. nager Tom Stapleton says will "force ,~.d'... r ¥*.>%, ' ~ '*04.-0.-5- -·*.1. the non-union employer to operate by , our standards" has been ratified by an overwhelming majority ofLocal 3 mem- bers who attended a series of ratif- ~,·, - -·¥ ·-'-. ':'.. *, ·,t "· . t i -r .*# ication meetings this month in Northern 4 '. California. 4'Mi'"73./3,4,«:' .W''~f:* 'Lk"/.: e •„*•L#. 4,*~ptk. The new agreement, which applies to employers in Northern California be- Business Manager Tom Stapleton and the longing to the Associated General negotiating committee discuss Contractors of California, the As- contract proposals with AGC representatives. sociation of Engineering Construction new language on the bidding of public hardest, but non-union contractors are Labor wins key Employers and all independent con- works projects, the creation of"Market also winning major public works pro- tractors bound by the "Short Form" and Geographic Committees" and a jects in urban areas, a trend that was victory by killing * agreement, was ratified by 93 percent of complete overhaul of the job class- almost nonexistent three years ago. t"or those who attended a round of 15 ifications. -

The Route Towards the Shawshank Redemption: Mapping Set-Jetting with Social Media and Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Of

The Route Towards The Shawshank Redemption: Mapping Set-jetting with Social Media Mengqian Yang A Thesis in The Department of Geography, Planning & Environment Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science (Geography, Urban and Environmental Studies) at Concordia University Montreal, Quebec, Canada August 2015 © Mengqian Yang, 2015 CONCORDIA UNIVERSITY School of Graduate Studies This is to certify that the thesis prepared By: Mengqian Yang Entitled: The Route Towards The Shawshank Redemption: Mapping Set-jetting with Social Media and submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science (Geography, Urban and Environmental Studies) complies with the regulations of the University and meets the accepted standards with respect to originality and quality. Signed by the final Examining Committee: Dr. Pascale Biron Chair Dr. Thierry Joliveau Examiner Dr. Christian Poirier Examiner Dr. Sébastien Caquard Supervisor Approved by Chair of Department or Graduate Program Director Dean of Faculty 2015 Date ABSTRACT The Route Towards The Shawshank Redemption: Mapping Set-jetting with Social Media Mengqian Yang With the development of the Web 2.0, more and more geospatial data are generated via social media. This segment of what is now called “big data” can be used to further study human spatial behaviors and practices. This project aims to explore different ways of extracting geodata from social media in order to contribute to the growing body of literature dedicated to studying the contribution of the geoweb to human geography. More specifically, this project focuses on the potential of social media to explore a growing tourism phenomenon: set-jetting. -

British Poetry of the Long Nineteenth Century

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Zea E-Books Zea E-Books 12-1-2019 British Poetry of the Long Nineteenth Century Beverley Rilett University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/zeabook Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Recommended Citation Rilett, Beverley, "British Poetry of the Long Nineteenth Century" (2019). Zea E-Books. 81. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/zeabook/81 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Zea E-Books at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Zea E-Books by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. British Poetry of the Long Nineteenth Century A Selection for College Students Edited by Beverley Park Rilett, PhD. CHARLOTTE SMITH WILLIAM BLAKE WILLIAM WORDSWORTH SAMUEL TAYLOR COLERIDGE GEORGE GORDON BYRON PERCY BYSSHE SHELLEY JOHN KEATS ELIZABETH BARRETT BROWNING ALFRED TENNYSON ROBERT BROWNING EMILY BRONTË GEORGE ELIOT MATTHEW ARNOLD GEORGE MEREDITH DANTE GABRIEL ROSSETTI CHRISTINA ROSSETTI OSCAR WILDE MARY ELIZABETH COLERIDGE ZEA BOOKS LINCOLN, NEBRASKA ISBN 978-1-60962-163-6 DOI 10.32873/UNL.DC.ZEA.1096 British Poetry of the Long Nineteenth Century A Selection for College Students Edited by Beverley Park Rilett, PhD. University of Nebraska —Lincoln Zea Books Lincoln, Nebraska Collection, notes, preface, and biographical sketches copyright © 2017 by Beverly Park Rilett. All poetry and images reproduced in this volume are in the public domain. ISBN: 978-1-60962-163-6 doi 10.32873/unl.dc.zea.1096 Cover image: The Lady of Shalott by John William Waterhouse, 1888 Zea Books are published by the University of Nebraska–Lincoln Libraries. -

Reading Stephen King: Issues of Censorship, Student Choice, and Popular Literature

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 414 606 CS 216 137 AUTHOR Power, Brenda Miller, Ed.; Wilhelm, Jeffrey D., Ed.; Chandler, Kelly, Ed. TITLE Reading Stephen King: Issues of Censorship, Student Choice, and Popular Literature. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, IL. ISBN ISBN-0-8141-3905-1 PUB DATE 1997-00-00 NOTE 246p. AVAILABLE FROM National Council of Teachers of English, 1111 W. Kenyon Road, Urbana, IL 61801-1096 (Stock No. 39051-0015: $14.95 members, $19.95 nonmembers). PUB TYPE Collected Works - General (020) Opinion Papers (120) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC10 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Censorship; Critical Thinking; *Fiction; Literature Appreciation; *Popular Culture; Public Schools; Reader Response; *Reading Material Selection; Reading Programs; Recreational Reading; Secondary Education; *Student Participation IDENTIFIERS *Contemporary Literature; Horror Fiction; *King (Stephen); Literary Canon; Response to Literature; Trade Books ABSTRACT This collection of essays grew out of the "Reading Stephen King Conference" held at the University of Mainin 1996. Stephen King's books have become a lightning rod for the tensions around issues of including "mass market" popular literature in middle and 1.i.gh school English classes and of who chooses what students read. King's fi'tion is among the most popular of "pop" literature, and among the most controversial. These essays spotlight the ways in which King's work intersects with the themes of the literary canon and its construction and maintenance, censorship in public schools, and the need for adolescent readers to be able to choose books in school reading programs. The essays and their authors are: (1) "Reading Stephen King: An Ethnography of an Event" (Brenda Miller Power); (2) "I Want to Be Typhoid Stevie" (Stephen King); (3) "King and Controversy in Classrooms: A Conversation between Teachers and Students" (Kelly Chandler and others); (4) "Of Cornflakes, Hot Dogs, Cabbages, and King" (Jeffrey D. -

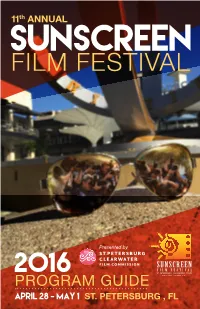

SUNSCREEN FILM FESTIVAL 2016 , |FL1 SECTION SECTION SECTION SECTION Table of TABLE OF

11 th ANNUAL SECTION SECTION CONTENT sunscreenCONTENT FILM FESTIVAL Presented by 2016 PROGRAM GUIDE SOUTH BAY - LOS ANGELES April 28 - May 1 ST. PETERSBURGSUNSCREEN FILM FESTIVAL 2016 , |FL1 SECTION SECTION SECTION SECTION Table of OF TABLE WHEN ALL OF YOU GET CONTENTS CONTENT BIG AND FAMOUS AND CONTENTS Welcome 4 CONTENT Box Office Information 5 Box Offices GO TO HOLLYWOOD Tickets & Passes Special Events Workshops PARTIES AND DRIVE Awards Ceremony & After Party AD Festival Schedule 6 - 7 Workshops & Panels 8 - 10 FLASHY CARS, Special Events Schedule 12 Opening Night Gala 13 Celebrity Guests 14 JUSTPAGE REMEMBER, Special Guests 15 - 20 Film Info and Schedule 22 - 48 Thursday • April 28 23 • 24 YOU’LL GET MORE FOR Friday • April 29 25 • 31 Saturday • April 30 32 • 40 YOUR MOVIE HERE. Sundauy • May 1 41 • 47 Sponsors 49 - 51 Get more for your movie here. PROUD SPONSOR OF THE SUNSCREEN FILM FESTIVAL 2 SUNSCREEN FILM FESTIVAL 2016 | 3 Sunscreen Film Festival ad 5x8.indd 1 4/7/2016 4:24:18 PM BOX OFFICE INFORMATION BOX OFFICE Regular Box Office opens Thursday, April 28 at the primary venue: American Stage, 163 3rd Street, North., St. Petersburg, Florida 33701. WELCOME BOX OFFICES INFORMATION Online Book tickets anytime day or night! Visit our website: www.SunscreenFilmFestival.com Festival Office American Stage. 163 3rd Street, North., St. Petersburg, Florida 33701 SOUTH BAY - LOS ANGELES Telephone Call (727) 259-8417 • Hours: 9:00 am - 5:00 pm • Monday - Sunday Visa and Mastercard, AMEX, Discover accepted at box office (at door) and Paypal accepted for advanced, online tickets and pass purchases. -

Reading Group Guide

FONT: Anavio regular (wwwUNDER.my nts.com) THE DOME ABOUT THE BOOK IN BRIEF: The idea for this story had its genesis in an unpublished novel titled The Cannibals which was about a group of inhabitants who find themselves trapped in their apartment building. In Under the Dome the story begins on a bright autumn morning, when a small Maine town is suddenly cut off from the rest of the world, and the inhabitants have to fight to survive. As food, electricity and water run short King performs an expert observation of human psychology, exploring how over a hundred characters deal with this terrifying scenario, bringing every one of his creations to three-dimensional life. Stephen King’s longest novel in many years, Under the Dome is a return to the large-scale storytelling of his ever-popular classic The Stand. IN DETAIL: Fast-paced, yet packed full of fascinating detail, the novel begins with a long list of characters, including three ‘dogs of note’ who were in Chester’s Mill on what comes to be known as ‘Dome Day’ — the day when the small Maine town finds itself forcibly isolated from the rest of America by an invisible force field. A woodchuck is chopped right in half; a gardener’s hand is severed at the wrist; a plane explodes with sheets of flame spreading to the ground. No one can get in and no one can get out. One of King’s great talents is his ability to alternate between large set-pieces and intimate moments of human drama, and King gets this balance exactly right in Under the Dome. -

Scary Movies at the Cudahy Family Library

SCARY MOVIES AT THE CUDAHY FAMILY LIBRARY prepared by the staff of the adult services department August, 2004 updated August, 2010 AVP: Alien Vs. Predator - DVD Abandoned - DVD The Abominable Dr. Phibes - VHS, DVD The Addams Family - VHS, DVD Addams Family Values - VHS, DVD Alien Resurrection - VHS Alien 3 - VHS Alien vs. Predator. Requiem - DVD Altered States - VHS American Vampire - DVD An American werewolf in London - VHS, DVD An American Werewolf in Paris - VHS The Amityville Horror - DVD anacondas - DVD Angel Heart - DVD Anna’s Eve - DVD The Ape - DVD The Astronauts Wife - VHS, DVD Attack of the Giant Leeches - VHS, DVD Audrey Rose - VHS Beast from 20,000 Fathoms - DVD Beyond Evil - DVD The Birds - VHS, DVD The Black Cat - VHS Black River - VHS Black X-Mas - DVD Blade - VHS, DVD Blade 2 - VHS Blair Witch Project - VHS, DVD Bless the Child - DVD Blood Bath - DVD Blood Tide - DVD Boogeyman - DVD The Box - DVD Brainwaves - VHS Bram Stoker’s Dracula - VHS, DVD The Brotherhood - VHS Bug - DVD Cabin Fever - DVD Candyman: Farewell to the Flesh - VHS Cape Fear - VHS Carrie - VHS Cat People - VHS The Cell - VHS Children of the Corn - VHS Child’s Play 2 - DVD Child’s Play 3 - DVD Chillers - DVD Chilling Classics, 12 Disc set - DVD Christine - VHS Cloverfield - DVD Collector - DVD Coma - VHS, DVD The Craft - VHS, DVD The Crazies - DVD Crazy as Hell - DVD Creature from the Black Lagoon - VHS Creepshow - DVD Creepshow 3 - DVD The Crimson Rivers - VHS The Crow - DVD The Crow: City of Angels - DVD The Crow: Salvation - VHS Damien, Omen 2 - VHS -

(Books): Dark Tower (Comics/Graphic

STEPHEN KING BOOKS: 11/22/63: HB, PB, pb, CD Audiobook 1922: PB American Vampire (Comics 1-5): Apt Pupil: PB Bachman Books: HB, pb Bag of Bones: HB, pb Bare Bones: Conversations on Terror with Stephen King: HB Bazaar of Bad Dreams: HB Billy Summers: HB Black House: HB, pb Blaze: (Richard Bachman) HB, pb, CD Audiobook Blockade Billy: HB, CD Audiobook Body: PB Carrie: HB, pb Cell: HB, PB Charlie the Choo-Choo: HB Christine: HB, pb Colorado Kid: pb, CD Audiobook Creepshow: Cujo: HB, pb Cycle of the Werewolf: PB Danse Macabre: HB, PB, pb, CD Audiobook Dark Half: HB, PB, pb Dark Man (Blue or Red Cover): DARK TOWER (BOOKS): Dark Tower I: The Gunslinger: PB, pb Dark Tower II: The Drawing Of Three: PB, pb Dark Tower III: The Waste Lands: PB, pb Dark Tower IV: Wizard & Glass: PB, PB, pb Dark Tower V: The Wolves Of Calla: HB, pb Dark Tower VI: Song Of Susannah: HB, PB, pb, pb, CD Audiobook Dark Tower VII: The Dark Tower: HB, PB, CD Audiobook Dark Tower: The Wind Through The Keyhole: HB, PB DARK TOWER (COMICS/GRAPHIC NOVELS): Dark Tower: The Gunslinger Born Graphic Novel HB, Comics 1-7 of 7 Dark Tower: The Gunslinger Born ‘2nd Printing Variant’ Comic 1 Dark Tower: The Long Road Home: Graphic Novel HB (x2) & Comics 1-5 of 5 Dark Tower: Treachery: Graphic Novel HB, Comics 1–6 of 6 Dark Tower: Treachery: ‘Midnight Opening Variant’ Comic 1 Dark Tower: The Fall of Gilead: Graphic Novel HB Dark Tower: Battle of Jericho Hill: Graphic Novel HB, Comics 2, 3, 5 of 5 Dark Tower: Gunslinger 1 – The Journey Begins: Comics 2 - 5 of 5 Dark Tower: Gunslinger 1 – -

Nosferatu. Revista De Cine (Donostia Kultura)

Nosferatu. Revista de cine (Donostia Kultura) Título: No diga bajo presupuesto, diga ... Roger Connan Autor/es: Valencia, Manuel Citar como: Valencia, M. (1994). No diga bajo presupuesto, diga ... Roger Connan. Nosferatu. Revista de cine. (14):79-89. Documento descargado de: http://hdl.handle.net/10251/40892 Copyright: Reserva de todos los derechos (NO CC) La digitalización de este artículo se enmarca dentro del proyecto "Estudio y análisis para el desarrollo de una red de conocimiento sobre estudios fílmicos a través de plataformas web 2.0", financiado por el Plan Nacional de I+D+i del Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad del Gobierno de España (código HAR2010-18648), con el apoyo de Biblioteca y Documentación Científica y del Área de Sistemas de Información y Comunicaciones (ASIC) del Vicerrectorado de las Tecnologías de la Información y de las Comunicaciones de la Universitat Politècnica de València. Entidades colaboradoras: Roger Corman :rj c--~- ~ c• 4 e :) ·~ No diga bajo presupuesto, diga ... Roger Corman Manuel Valencia í, bajo presupuesto, por céntimo, Ed. Laertes, Barcelona, los niveles de audiencia empeza que como bien explica el 1992), jamás realizó una pelícu ron a bajar, los estudios estimu Spropio Corman en su es la de serie B: "La serie B databa laban al público a ir al cine con pléndida y socarrona autobio de la Depresión, sólo fue un su el incentivo de los programas grafía (Cómo hice cien films en i·eso hasta principios de los años dobles, donde podían verse dos Hollywood y nunca perdí ni un cincuenta. En los treinta, cuando películas al precio de una. -

Sleeping Beauties Was Published

Turning Away from the Sun - through October 28th Featuring Abe Goodale 386 MAIN STREET ROCKLAND 207.596.0701 www.thearchipelago.net ISN’T THAT... Modern Family Dad Stephen casts no shadow over new generations of Kings. BY NINA LIVINGSTONE t 47 West Broadway in Bangor, three children grew up in 2009 a Gothic mansion surrounded by a black wrought-iron fence ss decorated with spiders, bats, and three-headed reptiles. AInside, Stephen and Tabitha King wrote novels while their kids experimented with their own TAGRAM; RU stories. Two of the children—both boys—would go on to become award-winning novelists, S N I and the eldest would take her writing talents to the pulpit and become a minister. IN THE BEGINNING As a fellow at the University of Maine, Tabitha immediately recognized her boyfriend’s gift, as she herself was a writer with an editor’s eye. In 1967, Stephen sold a short story to Star- FROM TOP: JOE HILL tling Mystery Stories—his first professional sale. The two married in 1971 shortly after grad- S E P T E M B E R 2 0 1 8 7 7 ISN’T THAT... From left to right: Joe, Tabitha, Kelly, Owen, Stephen, Naomi, and, McMurtry, Joe’s dog. T D MI H C S AERBEL B 7 8 PORT L AND M O N THLY MAGAZINE uation. While working to keep a roof over their heads and food on the table, they started a family, with Naomi their first born. When the novel Carrie skyrocketed Stephen into the recognition that had elud- ed him, his career was on its trajectory. -

Stephen-King-Book-List

BOOK NERD ALERT: STEPHEN KING ULTIMATE BOOK SELECTIONS *Short stories and poems on separate pages Stand-Alone Novels Carrie Salem’s Lot Night Shift The Stand The Dead Zone Firestarter Cujo The Plant Christine Pet Sematary Cycle of the Werewolf The Eyes Of The Dragon The Plant It The Eyes of the Dragon Misery The Tommyknockers The Dark Half Dolan’s Cadillac Needful Things Gerald’s Game Dolores Claiborne Insomnia Rose Madder Umney’s Last Case Desperation Bag of Bones The Girl Who Loved Tom Gordon The New Lieutenant’s Rap Blood and Smoke Dreamcatcher From a Buick 8 The Colorado Kid Cell Lisey’s Story Duma Key www.booknerdalert.com Last updated: 7/15/2020 Just After Sunset The Little Sisters of Eluria Under the Dome Blockade Billy 11/22/63 Joyland The Dark Man Revival Sleeping Beauties w/ Owen King The Outsider Flight or Fright Elevation The Institute Later Written by his penname Richard Bachman: Rage The Long Walk Blaze The Regulators Thinner The Running Man Roadwork Shining Books: The Shining Doctor Sleep Green Mile The Two Dead Girls The Mouse on the Mile Coffey’s Heads The Bad Death of Eduard Delacroix Night Journey Coffey on the Mile The Dark Tower Books The Gunslinger The Drawing of the Three The Waste Lands Wizard and Glass www.booknerdalert.com Last updated: 7/15/2020 Wolves and the Calla Song of Susannah The Dark Tower The Wind Through the Keyhole Talisman Books The Talisman Black House Bill Hodges Trilogy Mr. Mercedes Finders Keepers End of Watch Short