JOHANN GEORG HAMANN: Writings on Philosophy and Language

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

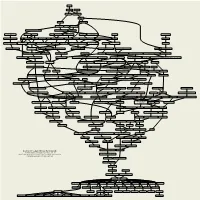

Academic Genealogy of George Em Karniadakis

Nilos Kabasilas Demetrios Kydones Elissaeus Judaeus Manuel Chrysoloras Georgios Plethon Gemistos 1380, 1393 Basilios Bessarion 1436 Mystras Guarino da Verona Johannes Argyropoulos 1408 1444 Università di Padova Vittorino da Feltre Cristoforo Landino Marsilio Ficino 1416 Università di Padova 1462 Università di Firenze Ognibene (Omnibonus Leonicenus) Bonisoli da Lonigo Theodoros Gazes Angelo Poliziano Università di Mantova 1433 Constantinople / Università di Mantova 1477 Università di Firenze Leo Outers Alessandro Sermoneta Gaetano da Thiene Moses Perez Scipione Fortiguerra Demetrios Chalcocondyles Jacob ben Jehiel Loans Rudolf Agricola Thomas à Kempis Heinrich von Langenstein 1485 Université Catholique de Louvain 1493 Università di Firenze 1452 Mystras / Accademia Romana 1478 Università degli Studi di Ferrara 1363, 1375 Université de Paris Maarten (Martinus Dorpius) van Dorp Pelope Pietro Roccabonella Nicoletto Vernia François Dubois Jean Tagault Girolamo (Hieronymus Aleander) Aleandro Janus Lascaris Matthaeus Adrianus Johann (Johannes Kapnion) Reuchlin Jan Standonck Alexander Hegius Johannes von Gmunden 1504, 1515 Université Catholique de Louvain Università di Padova Università di Padova 1516 Université de Paris 1499, 1508 Università di Padova 1472 Università di Padova 1477, 1481 Universität Basel / Université de Poitiers 1474, 1490 Collège Sainte-Barbe / Collège de Montaigu 1474 1406 Universität Wien Niccolò Leoniceno Jacobus (Jacques Masson) Latomus Desiderius Erasmus Petrus (Pieter de Corte) Curtius Pietro Pomponazzi Jacobus (Jacques -

Bischofswerda the Town and Its People Contents

Bischofswerda The town and its people Contents 0.1 Bischofswerda ............................................. 1 0.1.1 Geography .......................................... 1 0.1.2 History ............................................ 1 0.1.3 Sights ............................................. 2 0.1.4 Economy and traffic ...................................... 2 0.1.5 Culture and sports ....................................... 3 0.1.6 Partnership .......................................... 3 0.1.7 Personality .......................................... 3 0.1.8 Notes ............................................. 4 0.1.9 External links ......................................... 4 0.2 Großdrebnitz ............................................. 4 0.2.1 History ............................................ 4 0.2.2 People ............................................ 5 0.2.3 Literature ........................................... 6 0.2.4 Footnotes ........................................... 6 0.3 Wesenitz ................................................ 6 0.3.1 Geography .......................................... 6 0.3.2 Touristic Attractions ..................................... 6 0.3.3 Historical Usage ....................................... 7 0.3.4 Fauna ............................................. 7 0.3.5 References .......................................... 7 1 People born in or working for Bischofswerda 8 1.1 Abd-ru-shin .............................................. 8 1.1.1 Life, Publishing, Legacy ................................... 8 1.1.2 Legacy -

Christian Thomasius Briefwechsel Supplementband: Literaturverzeichnis Für Band 1

Christian Thomasius Briefwechsel Supplementband: Literaturverzeichnis für Band 1 Herausgegeben von Frank Grunert, Matthias Hambrock und Martin Kühnel Stand: 19.6.2018 www.thomasius-forschung.izea.uni-halle.de Das hier veröffentlichte Literaturverzeichnis ist auf dem Stand von Band 1 der Print-Ausgabe o „Christia Thoasius: Briefechsel. Historisch-kritische Editio“. Mit Erscheie eiterer Briefbände der Print-Ausgabe wird es neue, jeweils aktualisierte Online-Ausgaben dieses Literaturverzeichnisses geben. Online-Publikation www.thomasius-forschung.izea.uni-halle.de © 2018 bei den Herausgebern Layout: schwalbennest productions, Halle (Saale) Editorische Hinweise Die nachstehende Bibliografie bezieht sich auf Band 1 der Korrespondenz von Christian Thomasius.1 Sie umfasst zum einen alle Werke, die im Briefkorpus selbst genannt wer- den, zum anderen die zur Kommentierung der Briefe herangezogene Literatur. Die in Band 1 nahezu durchgehend nur mit Kurztitel aufgeführten Schriften werden hier mit ihren vollständigen bibliografischen Angaben aufgelistet. Literatur, die für die Recherche der biografischen Daten von Korrespondenten und er- wähnten Personen verwendet wurde, befindet sich im Personenlexikon,2 wo sie den be- treffenden biografischen Beiträgen zugeordnet ist. Das vorliegende Literaturverzeichnis wird in dieser Form ausschließlich online als PDF zur Verfügung gestellt. Mit Erscheinen jedes weiteren Briefbandes wird es überarbeitet werden und nach Fertigstellung der Edition als Teil des Supplements vollständig im Druck herauskommen. Das Verzeichnis gliedert sich in zwei große Teile: in die Werke von Thomasius sowie in sonstige (zeitgenössische und wissenschaftliche) Titel. Bei zeitgenössischen Werken erfolgt – wie im Verzeichnis der erwähnten Literatur in Band 1 – die Angabe der Titel zumeist nach der Autopsie des Titelblattes unter Belassung der orthografischen Beson- derheiten. Schriften, Zeitschriftenartikel, Lexikoneinträge etc. -

GREEK and LATIN CLASSICS V Blackwell’S Rare Books 48-51 Broad Street, Oxford, OX1 3BQ

Blackwell’s Rare Books Direct Telephone: +44 (0) 1865 333555 Switchboard: +44 (0) 1865 792792 Blackwell’S rare books Email: [email protected] Fax: +44 (0) 1865 794143 www.blackwell.co.uk/rarebooks GREEK AND LATIN CLASSICS V Blackwell’s Rare Books 48-51 Broad Street, Oxford, OX1 3BQ Direct Telephone: +44 (0) 1865 333555 Switchboard: +44 (0) 1865 792792 Email: [email protected] Fax: +44 (0) 1865 794143 www.blackwell.co.uk/ rarebooks Our premises are in the main Blackwell bookstore at 48-51 Broad Street, one of the largest and best known in the world, housing over 200,000 new book titles, covering every subject, discipline and interest, as well as a large secondhand books department. There is lift access to each floor. The bookstore is in the centre of the city, opposite the Bodleian Library and Sheldonian Theatre, and close to several of the colleges and other university buildings, with on street parking close by. Oxford is at the centre of an excellent road and rail network, close to the London - Birmingham (M40) motorway and is served by a frequent train service from London (Paddington). Hours: Monday–Saturday 9am to 6pm. (Tuesday 9:30am to 6pm.) Purchases: We are always keen to purchase books, whether single works or in quantity, and will be pleased to make arrangements to view them. Auction commissions: We attend a number of auction sales and will be happy to execute commissions on your behalf. Blackwell online bookshop www.blackwell.co.uk Our extensive online catalogue of new books caters for every speciality, with the latest releases and editor’s recommendations. -

Antiquarianism: a Reinterpretation Antiquarianism, the Early Modern

Antiquarianism: A Reinterpretation Kelsey Jackson Williams Accepted for publication in Erudition and the Republic of Letters, published by Brill. Antiquarianism, the early modern study of the past, occupies a central role in modern studies of humanist and post-humanist scholarship. Its relationship to modern disciplines such as archaeology is widely acknowledged, and at least some antiquaries--such as John Aubrey, William Camden, and William Dugdale--are well-known to Anglophone historians. But what was antiquarianism and how can twenty-first century scholars begin to make sense of it? To answer these questions, the article begins with a survey of recent scholarship, outlining how our understanding of antiquarianism has developed since the ground-breaking work of Arnaldo Momigliano in the mid-twentieth century. It then explores the definition and scope of antiquarian practice through close attention to contemporaneous accounts and actors’ categories before turning to three case-studies of antiquaries in Denmark, Scotland, and England. By way of conclusion, it develops a series of propositions for reassessing our understanding of antiquarianism. It reaffirms antiquarianism’s central role in the learned culture of the early modern world; and offers suggestions for avenues which might be taken in future research on the discipline. Antiquarianism: The State of the Field The days when antiquarianism could be dismissed as ‘a pedantic love of detail, with an indifference to the result’ have long since passed; their death-knell was rung by Arnaldo Momigliano in his pioneering 1950 ‘Ancient History and the Antiquarian’.1 Momigliano 1 asked three simple questions: What were the origins of antiquarianism? What role did it play in the eighteenth-century ‘reform of historical method’? Why did the distinction between antiquarianism and history collapse in the nineteenth century? The answers he gave continue to underpin the study of the discipline today. -

Elisabeth Leinfellner.Indd

Drei Pioniere der philosophisch-linguistischen Analyse von Zeit und Tempus: Mauthner, Jespersen, Reichenbach Elisabeth Leinfellner, Wien [A philosophical school in Tlön] reasons that the present is indefi nite, that the future has no reality other than as a present hope, that the past has no reality other than as a present memory. Jorge Luis Borges, Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius 1. Einleitung: die semantische Rolle der Tempora Unsere alltägliche, ,psychologische‘, aber auch die abstrakte newtonsche oder mathematische Vorstellung von Zeit – die ,klassischen‘ Zeitvorstellungen – laufen darauf hinaus, dass es eine einfache lineare Abfolge von Vergangen- heit-Gegenwart-Zukunft gibt. Analysiert man jedoch natürliche Sprachen, dann bietet sich ein anderes, komplexeres Bild: Würde man der einfachen, klassischen Vorstellung folgen, dann käme man in der Sprache mit drei Tempora aus: Präsens, Präteritum, Futurum. Ein Blick in die Grammatiken verschiedener Sprachen zeigt aber, dass es auch andere Tempora neben die- sen dreien gibt, so im heutigen Deutsch das Plusquamperfekt und das Fu- turum exactum. Gewisse Tempora und auch temporale Ersatzformen lösen mehr oder minder glücklich das Problem, dass z.B. in einer Erzählung im Präteritum manchmal auch im zeitlichen Rückgriff eine Vergangenheit vor der Vergangenheit dargestellt werden muss, oder eine Zukunft in der Ver- gangenheit. Die Ursachen für eine nicht chronologische Darstellung sind vielfältig, z.B. stilistisch-textliche oder dass wir uns an Ereignisse nicht im- mer in der richtigen Reihenfolge erinnern. Weiters muss die Verwendung der Tempora in erzählenden Texten die Rekonstruktion des chronologischen Ablaufs von Ereignissen erlauben, z.B. aus praktischen Gründen. Dass Texte keineswegs immer chronologisch geordnet sind, hat in verschiedenen Disziplinen und oft im Gefolge des russischen Formalismus zu einer Unterscheidung zwischen zwei zeitlichen Achsen geführt, der chronologischen Achse der Abfolge der Ereignisse, und F. -

Immanuel Kant Was Born in 1724, and Published “Religion Within The

CHAPTER FIVE THE PHENOMENOLOGY AND ‘FORMATIONS OF CONSCIOUSNESS’ It is this self-construing method alone which enables philosophy to be an objective, demonstrated science. (Hegel 1812) Immanuel Kant was born in 1724, and published “Religion within the limits of Reason” at the age of 70, at about the same time as the young Hegel was writing his speculations on building a folk religion at the seminary in Tübingen and Robespierre was engaged in his ultimately fatal practical experiment in a religion of Reason. Kant was a huge figure. Hegel and all his young philosopher friends were Kantians. But Kant’s system posed as many problems as it solved; to be a Kantian at that time was to be a participant in the project which Kant had initiated, the development of a philosophical system to fulfill the aims of the Enlightenment; and that generally meant critique of Kant. We need to look at just a couple of aspects of Kant’s philosophy which will help us understand Hegel’s approach. “I freely admit,” said Kant , “it was David Hume ’s remark [that Reason could not prove necessity or causality in Nature] that first, many years ago, interrupted my dogmatic slumber and gave a completely differ- ent direction to my enquiries in the field of speculative philosophy” (Kant 1997). Hume’s “Treatise on Human Nature” had been published while Kant was still very young, continuing a line of empiricists and their rationalist critics, whose concern was how knowledge and ideas originate from sensation. Hume was a skeptic; he demonstrated that causality could not be deduced from experience. -

A History of Women Philosophers Vol. IV

A HISTORY OF WOMEN PHILOSOPHERS A History of Women Philosophers 1. Ancient Women Philosophers, 600 B.C.-500 A.D. 2. Medieval, Renaissance and Enlightenment Women Philosophers, 500-1600 3. Modern Women Philosophers, 1600-1900 4. Contemporary Women Philosophers, 1900-today PROFESSOR C. J. DE VOGEL A History of Women Philosophers Volume 4 Contemporary Women Philosophers 1900-today Edited by MARY ELLEN WAITHE Cleveland State University, Cleveland, U.S.A. Springer-Science+Business Media, B. V. Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Contemporary women philosophers : 1900-today / edited by Mary Ellen Waithe. p. cm. -- (A History of women philosophers ; v. 4.) Includes bibliographical references (p. xxx-xxx) and index. ISBN 978-0-7923-2808-7 ISBN 978-94-011-1114-0 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-94-011-1114-0 1. Women philosophers. 2. Philosophy. Modern--20th century. r. Waithe. Mary Ellen. II. Series. Bl05.W6C66 1994 190' .82--dc20 94-9712 ISBN 978-0-7923-2808-7 printed an acid-free paper AII Rights Reserved © 1995 Springer Science+Business Media Dordrecht Originally published by Kluwer Academic Publishers in 1995 Softcover reprint ofthe hardcover lst edition 1995 No part of the material protected by this copyright notice may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from the copyright owner. Contents Acknowledgements xv Introduction to Volume 4, by Mary Ellen Waithe xix 1. Victoria, Lady Welby (1837-1912), by William Andrew 1 Myers I. Introduction 1 II. Biography 1 III. -

Bowliîo&Ebîstate University Library

THE DRAMATURGY OF LUDVIG HOLBERG'S COMEDIES Gerald S. Argetsinger A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY August 1975 BOWLIÎO&EBÎ STATE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY © 1975 GERALD SCOTT ARGETSINGER ALL RIGHTS RESERVED il ABSTRACT This study first described Ludvig Holberg's dramaturgy and then identified the characteristics which • have engendered the comedies' continued popularity. All of the prior Holberg research was studied, but most of the understanding of the comedies came through the careful studying of the playscripts. Holberg's form was greatly influenced by the comedies of Moliere and the Commedia dell' Arte. The content and tone were influenced by the comedies of Ben Jonson and George Farquhar. Holberg wrote for, and was best liked by, the middle class. At first, scholars found his plays crass and inferior. But only twenty years after his death, the plays were accepted as the foundation of the Royal Danish Theatre’s repertory. Holberg created comic characters based upon middle class types. The characters’ speech is almost strictly everyday, Copenhagen Danish. Little was done to linguistically individualize speech except when it was an integral part of the satire of the play. Holberg was also adept at writing jokes. He was a master at creating comic situations. These situations give the characters a setting in which to be funny and provide a foundation for intrigues and other comic business. The visual aspects of the early productions were not important. After careful investigation, it was concluded that Holberg's plays did not succeed, as previous writings tend to assume, because of the "Danishness” of the characters. -

Albert Schweitzer: a Man Between Two Cultures

, .' UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI'I LIBRARY ALBERT SCHWEITZER: A MAN BETWEEN TWO CULTURES A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI'I IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN LANGUAGES AND LITERATURES OF • EUROPE AND THE AMERICAS (GERMAN) MAY 2007 By Marie-Therese, Lawen Thesis Committee: Niklaus Schweizer Maryann Overstreet David Stampe We certify that we have read this thesis and that, in our opinion, it is satisfactory in scope and quality as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts in Languages and Literatures of Europe and the Americas (German). THESIS COMMITIEE --~ \ Ii \ n\.llm~~~il\I~lmll:i~~~10 004226205 ~. , L U::;~F H~' _'\ CB5 .H3 II no. 3Y 35 -- ,. Copyright 2007 by Marie-Therese Lawen 1II "..-. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS T I would like to express my deepest gratitude to a great number of people, without whose assistance, advice, and friendship this thesis w0l!'d not have been completed: Prof. Niklaus Schweizer has been an invaluable mentor and his constant support have contributed to the completion of this work; Prof. Maryann Overstreet made important suggestions about the form of the text and gave constructive criticism; Prof. David Stampe read the manuscript at different stages of its development and provided corrective feedback. 'My sincere gratitude to Prof. Jean-Paul Sorg for the the most interesting • conversations and the warmest welcome each time I visited him in Strasbourg. His advice and encouragement were highly appreciated. Further, I am deeply grateful for the help and advice of all who were of assistance along the way: Miriam Rappolt lent her editorial talents to finalize the text; Lynne Johnson made helpful suggestions about the chapter on Bach; John Holzman suggested beneficial clarifications. -

Satire and the Enlightenment Scandinavian R5B, Spring 2017

Satire and the Enlightenment Scandinavian R5B, Spring 2017 GSI: Zachary Blinkinsop Office: Dwinelle 6414 Office Hours: Monday and Wednesday 1200-1345 or by appointment Satire flourished during the eighteenth century when heavy-hitting writers across Europe penned droll attacks on superstition, intolerance, and vice. In this course, we will explore how the satirical mode functioned as part of the Enlightenment project. Particular emphasis will placed on the literary history of Sweden and Denmark-Norway from 1720 to 1792 and Ludvig Holberg’s satirical writings will comprise the mainstay of readings. Guiding questions in the course include: when is satire subversive and when does it reinforce the status quo? How do Scandinavian satires differ from their contemporaries in Great Britain, France, and colonial America/the United States? Is there a taxonomy of satire and what formal elements are ubiquitous across satirical sub-genres? Students will write a term paper that incorporates scholarship, historical material, and one or more of the course texts. All readings are in English. Course Texts (* indicates texts to purchase) Ogbord & Buckroyd * Satire Ebenezer Cooke “The Sot-Weed Factor” American, 1708 Ludvig Holberg Erasmus Montanus Danish, 1722 Ludvig Holberg Jeppe of the Hill Danish, 1723 Jonathan Swift Gulliver’s Travels Anglo-Irish, 1726 Jonathan Swift “A Modest Proposal” Anglo-Irish, 1729 Benjamin Franklin “The Witch Trial at Mount Holly” American, 1730 Olof Dalin “Proof of Wisdom: Mr. Arngrim Beserk” Swedish, 1739 Ludvig Holberg * The -

I. a Humanist John Merbecke

Durham E-Theses Renaissance humanism and John Merbecke's - The booke of Common praier noted (1550) Kim, Hyun-Ah How to cite: Kim, Hyun-Ah (2005) Renaissance humanism and John Merbecke's - The booke of Common praier noted (1550), Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/2767/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 Renaissance Humanism and John Merbecke's The booke of Common praier noted (1550) Hyun-Ah Kim A copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without his prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged. Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Durham University Department of Music Durham University .2005 m 2001 ABSTRACT Hyun-Ah Kim Renaissance Humanism and John Merbecke's The booke of Common praier noted (1550) Renaissance humanism was an intellectual technique which contributed most to the origin and development of the Reformation.