«Producing Music Is a Privilege» | Norient.Com 1 Oct 2021 03:13:01

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Elliott, 'This Is Our Grime'

Elliott, ‘This Is Our Grime’ ‘This Is Our Grime’: Encounter, Strangeness and Translation as Responses to Lisbon’s Batida Scene Richard Elliott Text of paper presented at the IASPM UK & Ireland Biennial Conference (‘London Calling’, online edition), 19 May 2020. A video of the presentation is available at the conference website. Introduction [SLIDE – kuduro/batida in Portugal] Batida (meaning ‘beat’ in Portuguese) is used as a collective term for recent forms of electronic dance music associated with the Afrodiasporic DJs of Lisbon, first- or second-generation immigrants from Portugal’s former colonies (especially Angola, Guinea Bissau, Cabo Verde and São Tomé e Príncipe). Batida is influenced – and seen as an evolution of – the EDM musics emanating from these countries, especially the kuduro and tarraxinha music of Angola. Like kuduro, this is a sound that – while occasionally making references to older styles – is contemporary music created on digital audio workstations such as FL Studio.1 Recent years have produced extensive coverage of the batida scene in English language publications such as Vice/Thump, FACT, The Wire and Resident Advisor. In a global EDM scene still dominated by Anglo-American understandings of popular music, batida is often compared to Chicago footwork and grime (just as fado has often been compared to the blues). The translation is a two-way process, with musicians taking on the role of explaining their music through extra-cultural references. This paper uses these attempts at musical translation as a prompt to explore issues of strangeness and encounter in responses to batida, and to situate them in the broader context of discourse around global pop. -

02 11 2016 01 01Tt0211wednesday EC 14

Sunday Times Combined Metros 14 - 01/11/2016 07:13:35 PM - Plate: 14 The Times Wednesday November 2 | 20 1 6 OUT AND ABOUT CINEMA PRIVÉ T his club’s the reel thing Jozi venue is a haven for film buffs, writes Ufrieda Ho JOZI after dark is full of hidden secrets, and one insider favourite is a 12-year-old club t h at consistently attracts film buffs. The Atlas Studio Film Club in Milpark was started in 2004 by Jonathan Gimpel, John Barker and Ziggy Hofmeyr as an informal gathering of film industry types. The monthly screening proved to be a hit and soon attracted a wider audience than STUDIO OF DREAMS: Jonathan Gimpel runs a cinema evening on the first Wednesday of every month at Atlas Studios Picture: ALON SKUY just the filmmaking community. Joburgers showed that they appreciated films that aren’t just big-screen CGI dramas and G i mp e l says he’s been blown away by the holiday and tidies them up. “The film club is not a highbrow arthouse regurgitated sequels. range of films he’s seen at the club. G i mp e l ’s collaborators in running movie thing, we’re very informal. Movies The club has been an opportunity for “Some of those stories stay with you. the club are Akin Omotoso, an actor and are, after all, about people’s stories.” networking and collaboration and is a venue There was a Korean film I can’t even filmmaker, and Katarina Hedrén, a film Showing under-represented films and to premiere films. -

FESTIVAL SÓNAR EN VENTA Barcelona 16.17.18 Junio

18º Festival Internacional de Música Avanzada y Arte Multimedia www.sonar.es Barcelona 16.17.18 Junio FESTIVAL SÓNAR EN VENTA Se vende festival anual con gran proyección internacional Razón: Sr. Samaniego +34 672 030 543 [email protected] 2 Sónar Conciertos y DJs Venta de entradas Sónar de Día Entradas ya a la venta. JUEVES 16 VIERNES 17 SÁBADO 18 Se recomienda la SonarVillage SonarVillage SonarVillage compra anticipada. by Estrella Damm by Estrella Damm by Estrella Damm 12:00 Ragul (ES) DJ 12:00 Neuron (ES) DJ 12:00 Nacho Bay (ES) DJ Aforos limitados. 13:30 Half Nelson + Vidal Romero 13:30 Joan S. Luna (ES) DJ 13:30 Judah (ES) DJ play Go Mag (ES) DJ 15:00 Facto y los Amigos del Norte (ES) Concierto 15:00 No Surrender (US) Concierto 15:00 Toro y Moi (US) Concierto 15:45 Agoria (FR) DJ 15:45 Gilles Peterson (UK) DJ Entradas y precios 16:00 Floating Points (UK) DJ 17:15 Atmosphere (US) Concierto 17:15 Yelawolf (US) Concierto 17:30 Little Dragon (SE) Concierto 18:15 DJ Raff (CL-ES) DJ 18:15 El Timbe (ES) DJ Abono: 155€ Ninja Tune & Big Dada presentan 19:15 Four Tet (UK) Concierto 19:15 Shangaan Electro (ZA) Concierto En las taquillas del festival: 165€ 18:30 Shuttle (US) DJ 20:00 Nacho Marco (ES) DJ 20:00 DJ Sith & David M (ES) DJ Entrada 1 día Sónar de Día: 39€ 19:30 Dels (UK) Concierto 21:00 Dominique Young Unique (US) Concierto 21:00 Filewile (CH) Concierto En las taquillas del festival: 45€ 20:15 Offshore (UK) DJ Entrada 1 día Sónar de Noche: 60€ 21:15 Eskmo (CH) Concierto SonarDôme SonarDôme En las taquillas del festival: 65€ L’Auditori: -

Alternate African Reality. Electronic, Electroacoustic and Experimental Music from Africa and the Diaspora

Alternate African Reality, cover for the digital release by Cedrik Fermont, 2020. Alternate African Reality. Electronic, electroacoustic and experimental music from Africa and the diaspora. Introduction and critique. "Always use the word ‘Africa’ or ‘Darkness’ or ‘Safari’ in your title. Subtitles may include the words ‘Zanzibar’, ‘Masai’, ‘Zulu’, ‘Zambezi’, ‘Congo’, ‘Nile’, ‘Big’, ‘Sky’, ‘Shadow’, ‘Drum’, ‘Sun’ or ‘Bygone’. Also useful are words such as ‘Guerrillas’, ‘Timeless’, ‘Primordial’ and ‘Tribal’. Note that ‘People’ means Africans who are not black, while ‘The People’ means black Africans. Never have a picture of a well-adjusted African on the cover of your book, or in it, unless that African has won the Nobel Prize. An AK-47, prominent ribs, naked breasts: use these. If you must include an African, make sure you get one in Masai or Zulu or Dogon dress." – Binyavanga Wainaina (1971-2019). © Binyavanga Wainaina, 2005. Originally published in Granta 92, 2005. Photo taken in the streets of Maputo, Mozambique by Cedrik Fermont, 2018. "Africa – the dark continent of the tyrants, the beautiful girls, the bizarre rituals, the tropical fruits, the pygmies, the guns, the mercenaries, the tribal wars, the unusual diseases, the abject poverty, the sumptuous riches, the widespread executions, the praetorian colonialists, the exotic wildlife - and the music." (extract from the booklet of Extreme Music from Africa (Susan Lawly, 1997). Whether intended as prank, provocation or patronisation or, who knows, all of these at once, producer William Bennett's fake African compilation Extreme Music from Africa perfectly fits the African clichés that Binyavanga Wainaina described in his essay How To Write About Africa : the concept, the cover, the lame references, the stereotypical drawing made by Trevor Brown.. -

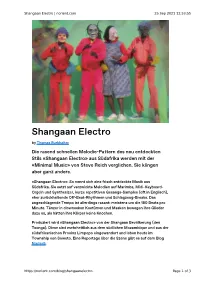

Shangaan Electro | Norient.Com 25 Sep 2021 12:53:55

Shangaan Electro | norient.com 25 Sep 2021 12:53:55 Shangaan Electro by Thomas Burkhalter Die rasend schnellen Melodie-Pattern des neu entdeckten Stils «Shangaan Electro» aus Südafrika werden mit der «Minimal Music» von Steve Reich verglichen. Sie klingen aber ganz anders. «Shangaan Electro»: So nennt sich eine frisch entdeckte Musik aus Südafrika. Sie setzt auf verzwickte Melodien auf Marimba, Midi-Keyboard- Orgeln und Synthesizer, kurze repetitiven Gesangs-Samples (oft in Englisch), eher zurückhaltende Off-Beat-Rhythmen und Schlagzeug-Breaks. Das angeschlagende Tempo ist allerdings rasant: meistens um die 180 Beats pro Minute. Tänzer in clownesken Kostümen und Masken bewegen ihre Glieder dazu so, als hätten ihre Körper keine Knochen. Produziert wird «Shangaan Electro» von der Shangaan Bevölkerung (den Tsonga). Diese sind mehrheitlich aus dem südlichen Mozambique und aus der südafrikanischen Provinz Limpopo eingewandert und leben heute im Township von Soweto. Eine Reportage über die Szene gibt es auf dem Blog Nialler9. https://norient.com/blog/shangaanelectro Page 1 of 3 Shangaan Electro | norient.com 25 Sep 2021 12:53:55 Das Genre «Shangaan» existiert schon lange, allerdings als elektrische (und nicht elektronische) Musik. George Maluleke und seine Band gelten als Pioniere dieses Stils. Der Blog 27 Leggies: Bringing Tsonga Music to the Masses schreibt: «He is 52, born and bred in Bangwani Village near Malamule, and has (or had in 2006) four wives and 14 children. It presumably must be a struggle to support so many by music alone, as "he also has two mini-buses which he bought with the proceeds of his albums". Or maybe they are just for transporting the family down to the shops.» Hier zwei Stücke von George Malukele: «Nizondha Swiendlo» (2003) und «Tinhlolo» (2005): Ausserhalb von Soweto war «Shangaan Electro» lange weitgehend unbekannt. -

Les Artistes Que Nous Avons Accueilli À La Péniche Cancale

Les artistes que nous avons accueilli à la Péniche Cancale En 2013 Concerts et Djs Groove (funk, hip hop, groove) Boom Bap, La Gougère, Mr Duterche, Mr Choubi, Green Shop, Freakistan, The Fat Bastard Gang Band, Shoota Family, Sax Machine, Mr Cheeky, Mr Hitchiker, Mounam, The Soul Funk Soldiers, Mr Crémant, Soul Food Party, Pop Corn à la plage, Anergy Afrobeat, Dj Jus d' Fruits, Giant Hip, Kunbe, Kiko Selecta, Kaktus Groove Band, Dj Buena Vibra, Funky People Party, The Britt Hörtefunk, Final Squeak, Looping Sound System, Giant Hip, The Mighty Mocambos, Boolimix, Alcor, Champion Sound, Ze Funky Brass Band, Whizzz Birthday Party Bituca, Luciano, Emilie Lesbros & Tiko invitent Boots Riley, Pira.ts, Reverie, Sparse « G-Funk » Selector, Lévi Flow, Novosonic's Friends Night, Prowpuskovic, Chylo, S.E.A.R., Clear Soul Forces. World (afro, reggae, latino, balkans, oriental, flamenco, trad) Coco Loco Party, G. Fandene Jah, Kiko Selecta, NMB Brass Band, Afrosoul Selecta, Boris Viande, Kutumba, Sô Kono Sound System, Akilisigui, Bamako Quintet, Joe Driscoll, Sekou Kouyaté, Boolimix, Alcor, Shakara, Djéli Moussa Condé, Stranded Horse, Boubacar Cissokho, Spirit’S, Pedrao e os Metropolitanos, Dj Nardin, Dj Malekoum, Trio Bassma, ChEmS, David Bruley Solo, Mr Presi, Dr Tribu, Zùz & Human Positiv Sound, Farafina Foli, Lalo Snitkin, Quincy St Love, Ziveli Orkestar, Trio Tarab. Rock (pop, folk, rock) I Love The Barmaid, The Chemist, Acevities, Fat Supper, Electric Bazar Cie, We are the sons of Faow Verny, Les Spadassins, Mr Duterche, The Astro Zombies, Oslow, Lullaby, Urban Sheep, Nahotchan, Nenad Sound System, Garce, King Automatic, The Fast Benderz, Battling, Le Grand Écart du Singe, 11 Louder, Ithak, Mr. -

Bidaia Margotuak Painted Trips Abuztua | Iraila August | September 83 83

bidaia margotuak painted trips abuztua | iraila august | september 83 83 the balde antsoain 1 31014 iruñea t. +34 948 12 19 76 f. +34 948 14 82 78 donostia ibilbidea. 11 behea 20115 astigarraga t. +34 943 44 44 22 f. +34 943 33 60 66 www.thebalde.net [email protected] [email protected] m. +34 686 485 980 harpidetzak / suscriptions: haizea bakedano perez argitaratzailea / publisher: eragin.com - azpikari sl editore / editor: iñigo martinez zuzendaria / director: koldo almandoz zuzendari komertziala & publizitatea / comercial director & publicity: iñigo martinez [email protected] +34 686 485 980 diseinua / design: martin etxauri, ekaitz auzmendi, eneko etxeandia itzulpenak / translations: 11itzulpen, smiley ale honetako kolaboratzaileak / collaborators this issue: arkaitz villar, aritz galarraga, federico babina, david zapirain, judas arrieta, uxeta labrit, agurtzane ortiz ale honetako argazkilariak / photographers this issue: anurson charoensuk, uxeta labrit, rebecca szeto, oskar alegria, matthias schaller, the balde crew azaleko irudia / cover image: anurson charoensuk aurkibidea / sumary: otomotake estudio harpidetza orria / subscription page: otomotake estudio inprimategia / printed at: gráficas alzate lege gordailua / legal: na-3244/01 the baldek sortutako eduki guztiek honako lizentzia pean daude: Aitortu-EzKomertziala-LanEratorririkGabe 2.5 Espainia Aske zara: lan hau kopiatu, banatu eta jendaurrean hedatzeko ondorengo helbidean zehazten diren baldintza zehatzetan: http://www.thebalde.net/lizentzia Lan berritzaile, irudimentsu eta ausartak egiten dituzula? bidali iezazkiguzu: Imaginative, provocative and interesting works? send them to: [email protected] LABURRAK IN BRIEF gtv images gtv images GTA V bideojoko ezagunera jolasten duen Morten Rockford Ravn takes photos of the bitartean, begi aurrean duen pantailan azaltzen situations and scenery he sees on the screen diren egoerei eta paisaiei argazkiak ateratzen while he plays GTA V. -

BOURGES Exposition Collective

1984 EDITIONS GRAPHOS OÏ OÏ (Graphzine) EXPOSITIONS « LIQUIDATION TOTALE » Musée de l’Ecole – BOURGES Exposition collective sur le thème : « Le Marché de l’Art et l’Art sur le marché » ave Karine Noulette – Elisabeth Delval – Béatrice Deloux – Florence Cotté – Jocelyne Vachet – Agnès Caffier – Alain Dubois. 1985 EDITIONS POLYZINE NOISE (Graphzine) EXPOSITIONS « COCKTAIL ROSE ET LUNETTES NOIRES » Musée de l’Ecole – BOURGES Exposition collective avec Florence Cotté – Rémi Grillet – Thomas – Nadia Delabarre. « ROLLMOPS THERMOSTAT 7 » Château d’Eau – BOURGES Exposition multi-média sur le thème : « L’objet et la société de consommation » avec Karine Noulette – Rémi Grillet – Nadia Delabarre – Elisabeth Delval – Béatrice Deloux – Christian Betrancourt – J-Christophe Dubois – Jocelyne Vachet – Etienne Cahurel – Richard Klein – Florence Cotté, concert de finissage avec : Matt Masson – S.M. Sophie – Opéra Multisteel – Dernière Criée. « AMBULANCE 15 » Entrepôt, Rue Albert Hervé – BOURGES 15 plasticiens exposent dans le cadre de la « Ruée vers l’Art ». Un exposant par jour avec Didier Som Wong – Dominique Moulon – Etienne Cahurel – Rémi Grillet – Sophie Babert – Lionel Chantillon – Christian Musio – Jocelyne Vachet – Gilles Bodeux – Alexis Mestre – Agnès Caffier – Dominique Stab – Nadia Delabarre – Christian Betrancourt – J-C Dubois – Karine Noulette – Elisabeth Delval – Laurence Dervaux. 1 Concert de finissage avec Hyppy S.M. Sophie – Sonorité Jaune – Baudritte – Grafuge – Entrerose – Les Endimanchés + Performance du peintre Sylvano Venturi (Forli -

JOBURG PARTY: a Snapshot of South Africa’S New Youth Underground a Film by Roderick Stanley & Chris Saunders

JOBURG PARTY: A snapshot of South Africa’s new youth underground A film by Roderick Stanley & Chris Saunders Starring Dirty Paraffin Richard the Third Desmond & The Tutus MJ Turpin Jamal Nxedlana (CUSS) Khaya Sibiya AKA Bhubessi. Joburg... It’s like a movie. “Everybody wants a piece of this African cake…” – Chocolate (rapper, entrepreneur, party animal) “Two days that look more like a week… Really interesting” – Die Zeit Contact Roderick Stanley [email protected] 646 639 3762 1 IN THE MEDIA “Un magnifique projet… A beautiful project illustrating the artistic richness of Johannesburg, often subject to violence and crime...” – Gradient Magazine “All too often Jo’burg is depicted as a dangerous and crime-filled city. However, over the last couple of years gentrification has swept through the city started by a movement of young creatives who are moving back to the centre of Johannesburg to live and work – proving that there is more to the city than meets the eye… This film is an interesting look at a city where young people from different cultural backgrounds are making it through a new wave of art, music and creativity.” – Connect / ZA “Two days that look more like a week… Joburg Party lasts just eight minutes. You would like to learn much more, because it seems really interesting what is being built there.” – Die Zeit WORD ON THE BLOGS “Check out this amazing brief documentary about the new youth underground movement in South Africa…” – AfroSuperstar “Chris Saunders and Rod Stanley made this great mini documentary on the Joburg street scene, check it out, it probably features some of your favourite South African artists.” – We Are Awesome “Cool story about the new youth movement in Johannesburg / South Africa… Super interesting, definitely check it out.” – WhuDat “Some fun reporting on the new urban underground subculture and the music it’s spawning in South Africa… Genuinely super interesting. -

El Latido Electrónico Africano En La Segunda Década Del Siglo Xxi1

NORBA. Revista de Arte, Vol. XXXIX (2019) 273-279, ISSN: 0213-2214 Doi: https://doi.org/10.17398/2660-714X.39.273 EL LATIDO ELECTRÓNICO AFRICANO EN LA SEGUNDA DÉCADA DEL SIGLO XXI1 AFRICAN ELECTRONIC HEARTBEAT IN THE SECOND DECADE OF THE 21ST CENTURY ALBERTO FLORES GALÁN Museo Vostell Malpartida Recibido: 21/04/2019 Aceptado: 29/09/2019 RESUMEN La investigación analiza un conjunto de propuestas electrónicas surgidas en la se- gunda década del siglo XXI que están definidas por la absorción de influencias africa- nas de diverso tipo. Palabras clave: Shangaan electro, gqom, singeli, balani show, Príncipe, Bamako, Dar es-Salam, Durban, Lisboa. ABSTRACT The research addresses a number of electronic proposals from the second decade of the 21st Century that absorb a wide range of African genres. Keywords: Shangaan electro, gqom, singeli, balani show, Príncipe, Bamako, Dar es Salaam, Durban, Lisbon. 1 Este texto ha sido posible gracias a la Ayuda del S.E.C.T.I. (Sistema Extremeño de Ciencia y Tecnología e Innovación) al Grupo de Investigación de la Junta de Extremadura “Arte y Patrimonio Moderno y Contemporáneo (HUM012)”. 274 ALBERTO FLORES GALÁN En los primeros lustros del siglo XXI los universos del arte sonoro y la música de vanguardia han experimentado algunos cambios sensibles, cuando no revolucionarios. En lo que se refiere a la creación electrónica que hunde sus raíces (y cables)2 en la tradición del continente negro una asombrosa variedad de músicas electrónicas han surgido de toda África en los últimos quince años3. De entre esta enorme diversidad (que oscila entre el kuduro angoleño, el mahraganat egipcio o el viaje de ida y vuelta realizado por el hip-hop, que en cierto modo regresó a la tierra y a la tradición oral de los griots) el estudio analiza aquellas propuestas que han sido celebradas en ámbitos especializados en el análisis de la experimentación sónica. -

Decoloniality and Actional Methodologies in Art and Cultural Practices in African Cultures of Technology

University of Plymouth PEARL https://pearl.plymouth.ac.uk 04 University of Plymouth Research Theses 01 Research Theses Main Collection 2018 POST AFRICAN FUTURES: Decoloniality and Actional Methodologies in Art and Cultural Practices in African Cultures of Technology Bristow, Tegan Mary http://hdl.handle.net/10026.1/10848 University of Plymouth All content in PEARL is protected by copyright law. Author manuscripts are made available in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite only the published version using the details provided on the item record or document. In the absence of an open licence (e.g. Creative Commons), permissions for further reuse of content should be sought from the publisher or author. Post African Futures by Tegan Bristow POST AFRICAN FUTURES: Decoloniality and Actional Methodologies in Art and Cultural Practices in African Cultures of Technology by Tegan Bristow A thesis submitted to Plymouth University in partial fulfilment for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 1 Post African Futures by Tegan Bristow Copyright Statement for PhD thesis titled: POST AFRICAN FUTURES: Decoloniality and Actional Methodologies in Art and Cultural Practices in African Cultures of Technology by Tegan Bristow (2018). This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with its author and that no quotation from the thesis and no information derived from it may be published without the author's prior consent. Signed by Author, 25th January 2018 2 Post African Futures by Tegan Bristow Abstract This thesis addresses the presence and role of critical aesthetic practices by cultural practitioners and creative technologists in addressing cultures of technology in contemporary African societies. -

Journey Into Sound Radio Darmstadt - Radar 103,4 Mhz / Livestream: Live.Radiodarmstadt.De Artist Track Album Label Sendetermin

On Air every months's first Thursday 2100 - 2300 CET Journey into Sound Radio Darmstadt - RadaR 103,4 MHz / Livestream: live.radiodarmstadt.de Artist Track Album Label Sendetermin !!! AM/FM Strange Weather, isn't it? Warp 01.07.2010 Individual Dance Safarai !!! Hello? Is this Thing on? Hello? Is this thing on? Warp 28.08.2004 Math on lone Beats !!! Hello? Is this Thing on? V/A Warp 02.12.2010 Warp20 (Elemental) Christmas Mix Vol. IX !!! Shit, Scheisse, Merde Pt.2 2 Tracks Clean Edits Warp 22.05.2004 A Doctor's Journey !!! Steady as the Sidewalk cracks Strange Weather, isn't it? Warp 02.09.2010 Sweet voodoo message music !!! Sunday 5:17 am Hello? Is this thing on? Warp 28.08.2004 Math on lone Beats !((OrKZa1 How to kill N'Sync How to kill N'Sync Commie 26.04.2003 Open word soundscapes (Read by) Andreas Pietschmann CD1 Carlos Ruiz Zafón - Der Schatten des Windes Hoffmann und Campe 05.07.2007 La Sombra del Viento (Read by) Andreas Pietschmann CD2 Carlos Ruiz Zafón - Der Schatten des Windes Hoffmann und Campe 05.07.2007 La Sombra del Viento (read by) Andreas Pietschmann Mpipidi und der Motlopi-Baum Nelson Mandela - Meine afrikanischen Hoffmann und Campe 29.05.2005 Lieblingsmärchen African Myths (read by) Christian Brückner Löwe , Hase und Hyäne Nelson Mandela - Meine afrikanischen Hoffmann und Campe 29.05.2005 Lieblingsmärchen African Myths (read by) Eva Mattes Die Schlange mit den 7 Köpfen Nelson Mandela - Meine afrikanischen Hoffmann und Campe 29.05.2005 Lieblingsmärchen African Myths (read by) Judy Winter Bescherung bei König Löwe Nelson Mandela - Meine afrikanischen Hoffmann und Campe 29.05.2005 Lieblingsmärchen African Myths (read by) Leslie Malton Die Mutter, die zu Staub zerfiel Nelson Mandela - Meine afrikanischen Hoffmann und Campe 29.05.2005 Lieblingsmärchen African Myths ..