Decoloniality and Actional Methodologies in Art and Cultural Practices in African Cultures of Technology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Elliott, 'This Is Our Grime'

Elliott, ‘This Is Our Grime’ ‘This Is Our Grime’: Encounter, Strangeness and Translation as Responses to Lisbon’s Batida Scene Richard Elliott Text of paper presented at the IASPM UK & Ireland Biennial Conference (‘London Calling’, online edition), 19 May 2020. A video of the presentation is available at the conference website. Introduction [SLIDE – kuduro/batida in Portugal] Batida (meaning ‘beat’ in Portuguese) is used as a collective term for recent forms of electronic dance music associated with the Afrodiasporic DJs of Lisbon, first- or second-generation immigrants from Portugal’s former colonies (especially Angola, Guinea Bissau, Cabo Verde and São Tomé e Príncipe). Batida is influenced – and seen as an evolution of – the EDM musics emanating from these countries, especially the kuduro and tarraxinha music of Angola. Like kuduro, this is a sound that – while occasionally making references to older styles – is contemporary music created on digital audio workstations such as FL Studio.1 Recent years have produced extensive coverage of the batida scene in English language publications such as Vice/Thump, FACT, The Wire and Resident Advisor. In a global EDM scene still dominated by Anglo-American understandings of popular music, batida is often compared to Chicago footwork and grime (just as fado has often been compared to the blues). The translation is a two-way process, with musicians taking on the role of explaining their music through extra-cultural references. This paper uses these attempts at musical translation as a prompt to explore issues of strangeness and encounter in responses to batida, and to situate them in the broader context of discourse around global pop. -

The State of Artistic Freedom 2021

THE STATE OF ARTISTIC FREEDOM 2021 THE STATE OF ARTISTIC FREEDOM 2021 1 Freemuse (freemuse.org) is an independent international non-governmental organisation advocating for freedom of artistic expression and cultural diversity. Freemuse has United Nations Special Consultative Status to the Economic and Social Council (UN-ECOSOC) and Consultative Status with UNESCO. Freemuse operates within an international human rights and legal framework which upholds the principles of accountability, participation, equality, non-discrimination and cultural diversity. We document violations of artistic freedom and leverage evidence-based advocacy at international, regional and national levels for better protection of all people, including those at risk. We promote safe and enabling environments for artistic creativity and recognise the value that art and culture bring to society. Working with artists, art and cultural organisations, activists and partners in the global south and north, we campaign for and support individual artists with a focus on artists targeted for their gender, race or sexual orientation. We initiate, grow and support locally owned networks of artists and cultural workers so their voices can be heard and their capacity to monitor and defend artistic freedom is strengthened. ©2021 Freemuse. All rights reserved. Design and illustration: KOPA Graphic Design Studio Author: Freemuse Freemuse thanks those who spoke to us for this report, especially the artists who took risks to take part in this research. We also thank everyone who stands up for the human right to artistic freedom. Every effort has been made to verify the accuracy of the information contained in this report. All information was believed to be correct as of February 2021. -

How to Play in a Band with 2 Chordal Instruments

FEBRUARY 2020 VOLUME 87 / NUMBER 2 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Reviews Editor Dave Cantor Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Will Dutton Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile Vice President of Sales 630-359-9345 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney Vice President of Sales 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Grace Blackford 630-359-9358 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Jeff Johnson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Andy Hermann, Sean J. O’Connell, Chris Walker, Josef Woodard, Scott Yanow; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Andrea Canter; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, Jennifer Odell; New York: Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Philip Freeman, Stephanie Jones, Matthew Kassel, Jimmy Katz, Suzanne Lorge, Phillip Lutz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Bill Milkowski, Allen Morrison, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian; Philadelphia: Shaun Brady; Portland: Robert Ham; San Francisco: Yoshi Kato, Denise Sullivan; Seattle: Paul de Barros; Washington, D.C.: Willard Jenkins, John Murph, Michael Wilderman; Canada: J.D. Considine, James Hale; France: Jean Szlamowicz; Germany: Hyou Vielz; Great Britain: Andrew Jones; Portugal: José Duarte; Romania: Virgil Mihaiu; Russia: Cyril Moshkow; South Africa: Don Albert. -

02 11 2016 01 01Tt0211wednesday EC 14

Sunday Times Combined Metros 14 - 01/11/2016 07:13:35 PM - Plate: 14 The Times Wednesday November 2 | 20 1 6 OUT AND ABOUT CINEMA PRIVÉ T his club’s the reel thing Jozi venue is a haven for film buffs, writes Ufrieda Ho JOZI after dark is full of hidden secrets, and one insider favourite is a 12-year-old club t h at consistently attracts film buffs. The Atlas Studio Film Club in Milpark was started in 2004 by Jonathan Gimpel, John Barker and Ziggy Hofmeyr as an informal gathering of film industry types. The monthly screening proved to be a hit and soon attracted a wider audience than STUDIO OF DREAMS: Jonathan Gimpel runs a cinema evening on the first Wednesday of every month at Atlas Studios Picture: ALON SKUY just the filmmaking community. Joburgers showed that they appreciated films that aren’t just big-screen CGI dramas and G i mp e l says he’s been blown away by the holiday and tidies them up. “The film club is not a highbrow arthouse regurgitated sequels. range of films he’s seen at the club. G i mp e l ’s collaborators in running movie thing, we’re very informal. Movies The club has been an opportunity for “Some of those stories stay with you. the club are Akin Omotoso, an actor and are, after all, about people’s stories.” networking and collaboration and is a venue There was a Korean film I can’t even filmmaker, and Katarina Hedrén, a film Showing under-represented films and to premiere films. -

FESTIVAL SÓNAR EN VENTA Barcelona 16.17.18 Junio

18º Festival Internacional de Música Avanzada y Arte Multimedia www.sonar.es Barcelona 16.17.18 Junio FESTIVAL SÓNAR EN VENTA Se vende festival anual con gran proyección internacional Razón: Sr. Samaniego +34 672 030 543 [email protected] 2 Sónar Conciertos y DJs Venta de entradas Sónar de Día Entradas ya a la venta. JUEVES 16 VIERNES 17 SÁBADO 18 Se recomienda la SonarVillage SonarVillage SonarVillage compra anticipada. by Estrella Damm by Estrella Damm by Estrella Damm 12:00 Ragul (ES) DJ 12:00 Neuron (ES) DJ 12:00 Nacho Bay (ES) DJ Aforos limitados. 13:30 Half Nelson + Vidal Romero 13:30 Joan S. Luna (ES) DJ 13:30 Judah (ES) DJ play Go Mag (ES) DJ 15:00 Facto y los Amigos del Norte (ES) Concierto 15:00 No Surrender (US) Concierto 15:00 Toro y Moi (US) Concierto 15:45 Agoria (FR) DJ 15:45 Gilles Peterson (UK) DJ Entradas y precios 16:00 Floating Points (UK) DJ 17:15 Atmosphere (US) Concierto 17:15 Yelawolf (US) Concierto 17:30 Little Dragon (SE) Concierto 18:15 DJ Raff (CL-ES) DJ 18:15 El Timbe (ES) DJ Abono: 155€ Ninja Tune & Big Dada presentan 19:15 Four Tet (UK) Concierto 19:15 Shangaan Electro (ZA) Concierto En las taquillas del festival: 165€ 18:30 Shuttle (US) DJ 20:00 Nacho Marco (ES) DJ 20:00 DJ Sith & David M (ES) DJ Entrada 1 día Sónar de Día: 39€ 19:30 Dels (UK) Concierto 21:00 Dominique Young Unique (US) Concierto 21:00 Filewile (CH) Concierto En las taquillas del festival: 45€ 20:15 Offshore (UK) DJ Entrada 1 día Sónar de Noche: 60€ 21:15 Eskmo (CH) Concierto SonarDôme SonarDôme En las taquillas del festival: 65€ L’Auditori: -

African Afro-Futurism: Allegories and Speculations

African Afro-futurism: Allegories and Speculations Gavin Steingo Introduction In his seminal text, More Brilliant Than The Sun, Kodwo Eshun remarks upon a general tension within contemporary African-American music: a tension between the “Soulful” and the “Postsoul.”1 While acknowledging that the two terms are always simultaneously at play, Eshun ultimately comes down strongly in favor of the latter. I quote him at length: Like Brussels sprouts, humanism is good for you, nourishing, nurturing, soulwarming—and from Phyllis Wheatley to R. Kelly, present-day R&B is a perpetual fight for human status, a yearning for human rights, a struggle for inclusion within the human species. Allergic to cybersonic if not to sonic technology, mainstream American media—in its drive to banish alienation, and to recover a sense of the whole human being through belief systems that talk to the “real you”—compulsively deletes any intimation of an AfroDiasporic futurism, of a “webbed network” of computerhythms, machine mythology and conceptechnics which routes, reroutes and criss- crosses the Atlantic. This digital diaspora connecting the UK to the US, the Caribbean to Europe to Africa, is in Paul Gilroy’s definition a “rhizo- morphic, fractal structure,” a “transcultural, international formation.” […] [By contrast] [t]he music of Alice Coltrane and Sun Ra, of Underground Resistance and George Russell, of Tricky and Martina, comes from the Outer Side. It alienates itself from the human; it arrives from the future. Alien Music is a synthetic recombinator, an applied art technology for amplifying the rates of becoming alien. Optimize the ratios of excentric- ity. Synthesize yourself. -

[email protected] Website: Nightshift.Oxfordmusic.Net Free Every Month

email: [email protected] website: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net Free every month. NIGHTSHIFT Issue 122 September Oxford’s Music Magazine 2005 SupergrassSupergrassSupergrass on a road less travelled plus 4-Page Truck Festival Review - inside NIGHTSHIFT: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU. Phone: 01865 372255 NEWNEWSS Nightshift: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU Phone: 01865 372255 email: [email protected] THE YOUNG KNIVES won You Now’, ‘Water and Wine’ and themselves a coveted slot at V ‘Gravity Flow’. In addition, the CD Festival last month after being comes with a bonus DVD which picked by Channel 4 and Virgin features a documentary following Mobile from over 1,000 new bands Mark over the past two years as he to open the festival on the Channel recorded the album, plus alternative 4 stage, alongside The Chemical versions of some tracks. Brothers, Doves, Kaiser Chiefs and The Magic Numbers. Their set was THE DOWNLOAD appears to have then broadcast by Channel 4. been given an indefinite extended Meanwhile, the band are currently in run by the BBC. The local music the studio with producer Andy Gill, show, which is broadcast on BBC recording their new single, ‘The Radio Oxford 95.2fm every Saturday THE MAGIC NUMBERS return to Oxford in November, leading an Decision’, due for release on from 6-7pm, has had a rolling impressive list of big name acts coming to town in the next few months. Transgressive in November. The monthly extension running through After their triumphant Truck Festival headline set last month, The Magic th Knives have also signed a publishing the summer, and with the positive Numbers (pictured) play at Brookes University on Tuesday 11 October. -

Best of 2012

http://www.afropop.org/wp/6228/stocking-stuffers-2012/ Best of 2012 Ases Falsos - Juventud Americana Xoél López - Atlantico Temperance League - Temperance League Dirty Projectors - Swing Lo Magellan Protistas - Las Cruces David Byrne & St Vincent - Love This Giant Los Punsetes - Una montaña es una montaña Patterson Hood - Heat Lightning Rumbles in the Distance Debo Band - Debo Band Ulises Hadjis - Cosas Perdidas Dr. John - Locked Down Ondatrópica - Ondatrópica Cat Power - Sun Love of Lesbian - La noche eterna. Los días no vividos Café Tacvba - El objeto antes llamado disco Chuck Prophet - Temple Beautiful Hello Seahorse! - Arunima Campo - Campo Tame Impala - Lonerism Juan Cirerol - Haciendo Leña Mokoomba - Rising Tide Lee Fields & The Expressions - Faithful Man Leon Larregui - Solstis Father John Misty - Fear Fun http://www.bestillplease.com/ There’s still plenty of time to hit the open road for a good summer road trip. Put your shades on, roll down the windows, crank up the tunes and start cruising. Here are some of CBC World's top grooves for the summer of 2012. These are songs that have a real rhythm and a sunny, happy, high-energy vibe to them. 6. Mokoomba, “Njoka.” Mokoomba is a band from the Victoria Falls area of Zimbabwe, made up of musicians from the Tonga people of Zimbabwe. The textures on this first single, from Mokoomba's second album Rising Tide, are great, especially the vocals http://music.cbc.ca/#/blogs/2012/8/Road-trip-playlist-with-Quantic-the-Very-Best-Refugee-All-Stars-more CHARTS & LISTS AFRICAN MUSIC: THE BEST OF 2012. This list considers only new, original studio recordings released this year. -

Live Music Audiences Johannesburg (Gauteng) South Africa

Live Music Audiences Johannesburg (Gauteng) South Africa 1 Live Music and Audience Development The role and practice of arts marketing has evolved over the last decade from being regarded as subsidiary to a vital function of any arts and cultural organisation. Many organisations have now placed the audience at the heart of their operation, becoming artistically-led, but audience-focused. Artistically-led, audience-focused organisations segment their audiences into target groups by their needs, motivations and attitudes, rather than purely their physical and demographic attributes. Finally, they adapt the audience experience and marketing approach for each target groupi. Within the arts marketing profession and wider arts and culture sector, a new Anglo-American led field has emerged, called audience development. While the definition of audience development may differ among academics, it’s essentially about: understanding your audiences through research; becoming more audience-focused (or customer-centred); and seeking new audiences through short and long-term strategies. This report investigates what importance South Africa places on arts marketing and audiences as well as their current understanding of, and appetite for, audience development. It also acts as a roadmap, signposting you to how the different aspects of the research can be used by arts and cultural organisations to understand and grow their audiences. While audience development is the central focus of this study, it has been located within the live music scene in Johannesburg and wider Gauteng. Emphasis is also placed on young audiences as they represent a large existing, and important potential, audience for the live music and wider arts sector. -

Alternate African Reality. Electronic, Electroacoustic and Experimental Music from Africa and the Diaspora

Alternate African Reality, cover for the digital release by Cedrik Fermont, 2020. Alternate African Reality. Electronic, electroacoustic and experimental music from Africa and the diaspora. Introduction and critique. "Always use the word ‘Africa’ or ‘Darkness’ or ‘Safari’ in your title. Subtitles may include the words ‘Zanzibar’, ‘Masai’, ‘Zulu’, ‘Zambezi’, ‘Congo’, ‘Nile’, ‘Big’, ‘Sky’, ‘Shadow’, ‘Drum’, ‘Sun’ or ‘Bygone’. Also useful are words such as ‘Guerrillas’, ‘Timeless’, ‘Primordial’ and ‘Tribal’. Note that ‘People’ means Africans who are not black, while ‘The People’ means black Africans. Never have a picture of a well-adjusted African on the cover of your book, or in it, unless that African has won the Nobel Prize. An AK-47, prominent ribs, naked breasts: use these. If you must include an African, make sure you get one in Masai or Zulu or Dogon dress." – Binyavanga Wainaina (1971-2019). © Binyavanga Wainaina, 2005. Originally published in Granta 92, 2005. Photo taken in the streets of Maputo, Mozambique by Cedrik Fermont, 2018. "Africa – the dark continent of the tyrants, the beautiful girls, the bizarre rituals, the tropical fruits, the pygmies, the guns, the mercenaries, the tribal wars, the unusual diseases, the abject poverty, the sumptuous riches, the widespread executions, the praetorian colonialists, the exotic wildlife - and the music." (extract from the booklet of Extreme Music from Africa (Susan Lawly, 1997). Whether intended as prank, provocation or patronisation or, who knows, all of these at once, producer William Bennett's fake African compilation Extreme Music from Africa perfectly fits the African clichés that Binyavanga Wainaina described in his essay How To Write About Africa : the concept, the cover, the lame references, the stereotypical drawing made by Trevor Brown.. -

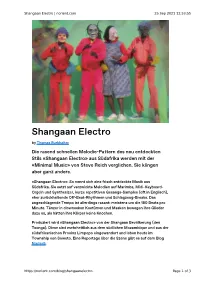

Shangaan Electro | Norient.Com 25 Sep 2021 12:53:55

Shangaan Electro | norient.com 25 Sep 2021 12:53:55 Shangaan Electro by Thomas Burkhalter Die rasend schnellen Melodie-Pattern des neu entdeckten Stils «Shangaan Electro» aus Südafrika werden mit der «Minimal Music» von Steve Reich verglichen. Sie klingen aber ganz anders. «Shangaan Electro»: So nennt sich eine frisch entdeckte Musik aus Südafrika. Sie setzt auf verzwickte Melodien auf Marimba, Midi-Keyboard- Orgeln und Synthesizer, kurze repetitiven Gesangs-Samples (oft in Englisch), eher zurückhaltende Off-Beat-Rhythmen und Schlagzeug-Breaks. Das angeschlagende Tempo ist allerdings rasant: meistens um die 180 Beats pro Minute. Tänzer in clownesken Kostümen und Masken bewegen ihre Glieder dazu so, als hätten ihre Körper keine Knochen. Produziert wird «Shangaan Electro» von der Shangaan Bevölkerung (den Tsonga). Diese sind mehrheitlich aus dem südlichen Mozambique und aus der südafrikanischen Provinz Limpopo eingewandert und leben heute im Township von Soweto. Eine Reportage über die Szene gibt es auf dem Blog Nialler9. https://norient.com/blog/shangaanelectro Page 1 of 3 Shangaan Electro | norient.com 25 Sep 2021 12:53:55 Das Genre «Shangaan» existiert schon lange, allerdings als elektrische (und nicht elektronische) Musik. George Maluleke und seine Band gelten als Pioniere dieses Stils. Der Blog 27 Leggies: Bringing Tsonga Music to the Masses schreibt: «He is 52, born and bred in Bangwani Village near Malamule, and has (or had in 2006) four wives and 14 children. It presumably must be a struggle to support so many by music alone, as "he also has two mini-buses which he bought with the proceeds of his albums". Or maybe they are just for transporting the family down to the shops.» Hier zwei Stücke von George Malukele: «Nizondha Swiendlo» (2003) und «Tinhlolo» (2005): Ausserhalb von Soweto war «Shangaan Electro» lange weitgehend unbekannt. -

Encyclopedia of African American Music Advisory Board

Encyclopedia of African American Music Advisory Board James Abbington, DMA Associate Professor of Church Music and Worship Candler School of Theology, Emory University William C. Banfield, DMA Professor of Africana Studies, Music, and Society Berklee College of Music Johann Buis, DA Associate Professor of Music History Wheaton College Eileen M. Hayes, PhD Associate Professor of Ethnomusicology College of Music, University of North Texas Cheryl L. Keyes, PhD Professor of Ethnomusicology University of California, Los Angeles Portia K. Maultsby, PhD Professor of Folklore and Ethnomusicology Director of the Archives of African American Music and Culture Indiana University, Bloomington Ingrid Monson, PhD Quincy Jones Professor of African American Music Harvard University Guthrie P. Ramsey, Jr., PhD Edmund J. and Louise W. Kahn Term Professor of Music University of Pennsylvania Encyclopedia of African American Music Volume 1: A–G Emmett G. Price III, Executive Editor Tammy L. Kernodle and Horace J. Maxile, Jr., Associate Editors Copyright 2011 by Emmett G. Price III, Tammy L. Kernodle, and Horace J. Maxile, Jr. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, except for the inclusion of brief quotations in a review, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Encyclopedia of African American music / Emmett G. Price III, executive editor ; Tammy L. Kernodle and Horace J. Maxile, Jr., associate editors. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-313-34199-1 (set hard copy : alk.