Channel Aggradation by Beaver Darns on a Small Agricultural Stream In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PRELUDE to SEVEN SLOTS: FILLING and SUBSEQUENT MODIFICATION of SEVEN BROAD CANYONS in the NAVAJO SANDSTONE, SOUTH-CENTRAL UTAH by David B

PRELUDE TO SEVEN SLOTS: FILLING AND SUBSEQUENT MODIFICATION OF SEVEN BROAD CANYONS IN THE NAVAJO SANDSTONE, SOUTH-CENTRAL UTAH by David B. Loope1, Ronald J. Goble1, and Joel P. L. Johnson2 ABSTRACT Within a four square kilometer portion of Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument, seven distinct slot canyons cut the Jurassic Navajo Sandstone. Four of the slots developed along separate reaches of a trunk stream (Dry Fork of Coyote Gulch), and three (including canyons locally known as “Peekaboo” and “Spooky”) are at the distal ends of south-flowing tributary drainages. All these slot canyons are examples of epigenetic gorges—bedrock channel reaches shifted laterally from previous reach locations. The previous channels became filled with alluvium, allowing active channels to shift laterally in places and to subsequently re-incise through bedrock elsewhere. New evidence, based on optically stimulated luminescence (OSL) ages, indicates that this thick alluvium started to fill broad, pre-existing, bedrock canyons before 55,000 years ago, and that filling continued until at least 48,000 years ago. Streams start to fill their channels when sediment supply increases relative to stream power. The following conditions favored alluviation in the study area: (1) a cooler, wetter climate increased the rate of mass wasting along the Straight Cliffs (the headwaters of Dry Fork) and the rate of weathering of the broad outcrops of Navajo and Entrada Sandstone; (2) windier conditions increased the amount of eolian sand transport, perhaps destabilizing dunes and moving their stored sediment into stream channels; and (3) southward migration of the jet stream dimin- ished the frequency and severity of convective storms. -

Lesson 4: Sediment Deposition and River Structures

LESSON 4: SEDIMENT DEPOSITION AND RIVER STRUCTURES ESSENTIAL QUESTION: What combination of factors both natural and manmade is necessary for healthy river restoration and how does this enhance the sustainability of natural and human communities? GUIDING QUESTION: As rivers age and slow they deposit sediment and form sediment structures, how are sediments and sediment structures important to the river ecosystem? OVERVIEW: The focus of this lesson is the deposition and erosional effects of slow-moving water in low gradient areas. These “mature rivers” with decreasing gradient result in the settling and deposition of sediments and the formation sediment structures. The river’s fast-flowing zone, the thalweg, causes erosion of the river banks forming cliffs called cut-banks. On slower inside turns, sediment is deposited as point-bars. Where the gradient is particularly level, the river will branch into many separate channels that weave in and out, leaving gravel bar islands. Where two meanders meet, the river will straighten, leaving oxbow lakes in the former meander bends. TIME: One class period MATERIALS: . Lesson 4- Sediment Deposition and River Structures.pptx . Lesson 4a- Sediment Deposition and River Structures.pdf . StreamTable.pptx . StreamTable.pdf . Mass Wasting and Flash Floods.pptx . Mass Wasting and Flash Floods.pdf . Stream Table . Sand . Reflection Journal Pages (printable handout) . Vocabulary Notes (printable handout) PROCEDURE: 1. Review Essential Question and introduce Guiding Question. 2. Hand out first Reflection Journal page and have students take a minute to consider and respond to the questions then discuss responses and questions generated. 3. Handout and go over the Vocabulary Notes. Students will define the vocabulary words as they watch the PowerPoint Lesson. -

Geomorphic Classification of Rivers

9.36 Geomorphic Classification of Rivers JM Buffington, U.S. Forest Service, Boise, ID, USA DR Montgomery, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA Published by Elsevier Inc. 9.36.1 Introduction 730 9.36.2 Purpose of Classification 730 9.36.3 Types of Channel Classification 731 9.36.3.1 Stream Order 731 9.36.3.2 Process Domains 732 9.36.3.3 Channel Pattern 732 9.36.3.4 Channel–Floodplain Interactions 735 9.36.3.5 Bed Material and Mobility 737 9.36.3.6 Channel Units 739 9.36.3.7 Hierarchical Classifications 739 9.36.3.8 Statistical Classifications 745 9.36.4 Use and Compatibility of Channel Classifications 745 9.36.5 The Rise and Fall of Classifications: Why Are Some Channel Classifications More Used Than Others? 747 9.36.6 Future Needs and Directions 753 9.36.6.1 Standardization and Sample Size 753 9.36.6.2 Remote Sensing 754 9.36.7 Conclusion 755 Acknowledgements 756 References 756 Appendix 762 9.36.1 Introduction 9.36.2 Purpose of Classification Over the last several decades, environmental legislation and a A basic tenet in geomorphology is that ‘form implies process.’As growing awareness of historical human disturbance to rivers such, numerous geomorphic classifications have been de- worldwide (Schumm, 1977; Collins et al., 2003; Surian and veloped for landscapes (Davis, 1899), hillslopes (Varnes, 1958), Rinaldi, 2003; Nilsson et al., 2005; Chin, 2006; Walter and and rivers (Section 9.36.3). The form–process paradigm is a Merritts, 2008) have fostered unprecedented collaboration potentially powerful tool for conducting quantitative geo- among scientists, land managers, and stakeholders to better morphic investigations. -

River Dynamics 101 - Fact Sheet River Management Program Vermont Agency of Natural Resources

River Dynamics 101 - Fact Sheet River Management Program Vermont Agency of Natural Resources Overview In the discussion of river, or fluvial systems, and the strategies that may be used in the management of fluvial systems, it is important to have a basic understanding of the fundamental principals of how river systems work. This fact sheet will illustrate how sediment moves in the river, and the general response of the fluvial system when changes are imposed on or occur in the watershed, river channel, and the sediment supply. The Working River The complex river network that is an integral component of Vermont’s landscape is created as water flows from higher to lower elevations. There is an inherent supply of potential energy in the river systems created by the change in elevation between the beginning and ending points of the river or within any discrete stream reach. This potential energy is expressed in a variety of ways as the river moves through and shapes the landscape, developing a complex fluvial network, with a variety of channel and valley forms and associated aquatic and riparian habitats. Excess energy is dissipated in many ways: contact with vegetation along the banks, in turbulence at steps and riffles in the river profiles, in erosion at meander bends, in irregularities, or roughness of the channel bed and banks, and in sediment, ice and debris transport (Kondolf, 2002). Sediment Production, Transport, and Storage in the Working River Sediment production is influenced by many factors, including soil type, vegetation type and coverage, land use, climate, and weathering/erosion rates. -

Federal Agency Functional Activities

Appendix B – Federal Agency Functional Activities Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) Point of Contact: Wyeth (Chad) Wallace, (720) 407-0638 The mission of the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) is to enhance the quality of life, to promote economic opportunity, and to carry out the responsibility to protect and improve the trust assets of American Indians, Indian tribes, and Alaska Natives. Divided into regions (see map), the BIA is responsible for the administration and management of 55 million surface acres and 57 million acres of subsurface minerals estates held in trust by the United States for approximately 1.9 million American Indians and Alaska Natives, and 565 federally recognized American Indian tribes. The primary public policy of the Federal government in regards to Native Americans is the return of trust lands management responsibilities to those most affected by decisions on how these American Indian Trust (AIT) lands are to be used and developed. Enhanced elevation data, orthoimagery, and GIS technology are needed to enable tribal organizations to wholly manage significant, profitable and sustainable enterprises as diverse as forestry, water resources, mining, oil and gas, transportation, tourism, agriculture and range land leasing and management, while preserving and protecting natural and cultural resources on AIT lands. Accurate and current elevation data are especially mission-critical for management of forest and water resources. It is the mission of BIA’s Irrigation, Power and Safety of Dams (IPSOD) program to promote self-determination, economic opportunities and public safety through the sound management of irrigation, dam and power facilities owned by the BIA. This program generates revenues for the irrigation and power projects of $80M to $90M annually. -

Stream Restoration, a Natural Channel Design

Stream Restoration Prep8AICI by the North Carolina Stream Restonltlon Institute and North Carolina Sea Grant INC STATE UNIVERSITY I North Carolina State University and North Carolina A&T State University commit themselves to positive action to secure equal opportunity regardless of race, color, creed, national origin, religion, sex, age or disability. In addition, the two Universities welcome all persons without regard to sexual orientation. Contents Introduction to Fluvial Processes 1 Stream Assessment and Survey Procedures 2 Rosgen Stream-Classification Systems/ Channel Assessment and Validation Procedures 3 Bankfull Verification and Gage Station Analyses 4 Priority Options for Restoring Incised Streams 5 Reference Reach Survey 6 Design Procedures 7 Structures 8 Vegetation Stabilization and Riparian-Buffer Re-establishment 9 Erosion and Sediment-Control Plan 10 Flood Studies 11 Restoration Evaluation and Monitoring 12 References and Resources 13 Appendices Preface Streams and rivers serve many purposes, including water supply, The authors would like to thank the following people for reviewing wildlife habitat, energy generation, transportation and recreation. the document: A stream is a dynamic, complex system that includes not only Micky Clemmons the active channel but also the floodplain and the vegetation Rockie English, Ph.D. along its edges. A natural stream system remains stable while Chris Estes transporting a wide range of flows and sediment produced in its Angela Jessup, P.E. watershed, maintaining a state of "dynamic equilibrium." When Joseph Mickey changes to the channel, floodplain, vegetation, flow or sediment David Penrose supply significantly affect this equilibrium, the stream may Todd St. John become unstable and start adjusting toward a new equilibrium state. -

Channel Aggradation by Beaver Dams on a Small Agricultural Stream in Eastern Nebraska

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln U.S. Department of Agriculture: Agricultural Publications from USDA-ARS / UNL Faculty Research Service, Lincoln, Nebraska 9-12-2004 Channel Aggradation by Beaver Dams on a Small Agricultural Stream in Eastern Nebraska M. C. McCullough University of Nebraska-Lincoln J. L. Harper University of Nebraska-Lincoln D. E. Eisenhauer University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] M. G. Dosskey USDA National Agroforestry Center, Lincoln, Nebraska, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/usdaarsfacpub Part of the Agricultural Science Commons McCullough, M. C.; Harper, J. L.; Eisenhauer, D. E.; and Dosskey, M. G., "Channel Aggradation by Beaver Dams on a Small Agricultural Stream in Eastern Nebraska" (2004). Publications from USDA-ARS / UNL Faculty. 147. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/usdaarsfacpub/147 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the U.S. Department of Agriculture: Agricultural Research Service, Lincoln, Nebraska at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Publications from USDA-ARS / UNL Faculty by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. This is not a peer-reviewed article. Self-Sustaining Solutions for Streams, Wetlands, and Watersheds, Proceedings of the 12-15 September 2004 Conference (St. Paul, Minnesota USA) Publication Date 12 September 2004 ASAE Publication Number 701P0904. Ed. J. L. D'Ambrosio Channel Aggradation by Beaver Dams on a Small Agricultural Stream in Eastern Nebraska M. C. McCullough1, J. L. Harper2, D.E. Eisenhauer3, M. G. Dosskey4 ABSTRACT We assessed the effect of beaver dams on channel gradation of an incised stream in an agricultural area of eastern Nebraska. -

Seasonal Controls on Meteoric 7Be in Coarse‐Grained River Channels

HYDROLOGICAL PROCESSES Hydrol. Process. 28, 2738–2748 (2014) Published online 24 April 2013 in Wiley Online Library (wileyonlinelibrary.com) DOI: 10.1002/hyp.9800 Seasonal controls on meteoric 7Be in coarse-grained river channels James M. Kaste,1* Francis J. Magilligan,2 Carl E. Renshaw,2 G. Burch Fisher3 and W. Brian Dade2 1 Geology Department, The College of William & Mary, Williamsburg, VA, 23187, USA 2 Department of Earth Sciences, Dartmouth College, Hanover, NH, 03755, USA 3 Department of Earth Science, University of California, Santa Barbara, CA, 93106, USA Abstract: Cosmogenic 7Be is a natural tracer of short-term hydrological processes, but its distribution in upland fluvial environments over different temporal and spatial scales has not been well described. We measured 7Be in 450 sediment samples collected from perennial channels draining the middle of the Connecticut River Basin, an environment that is predominantly well-sorted sand. By sampling tributaries that have natural and managed fluctuations in discharge, we find that the 7Be activity in thalweg sediments is not necessarily limited by the supply of new or fine-grained sediment, but is controlled seasonally by atmospheric flux variations and the magnitude and frequency of bed mobilizing events. In late winter, 7Be concentrations in transitional bedload are lowest, typically 1 to 3 Bq kgÀ1 as 7Be is lost from watersheds via radioactive decay in the snowpack. In mid- summer, however, 7Be concentrations are at least twice as high because of increased convective storm activity which delivers high 7Be fluxes directly to the fluvial system. A mixed layer of sediment at least 8 cm thick is maintained for months in channels during persistent low rainfall and flow conditions, indicating that stationary sediments can be recharged with 7Be. -

Introduction to Morphodynamics of Sedimentary Patterns

MORPHODYNAMICS OF SEDIMENTARY PATTERNS Paolo Blondeaux, Marco Colombini, Giovanni Seminara, Giovanna Vittori Introduction to Morphodynamics of Sedimentary Patterns DIDATTICARICERCA RICERCA Genova University Press Monograph Series Morphodynamics of Sedimentary Patterns Editorial Board: Paolo Blondeaux, Marco Colombini Giovanni Seminara, Giovanna Vittori Advisory Board: Sivaramakrishnan Balachandar (University of Florida U.S.A.) Maurizio Brocchini (Università Politecnica delle Marche, Italy) François Charru (Université Paul Sabatier, France) Giovanni Coco (University of Auckland, New Zealand) Enrico Foti (Università di Catania, Italy) Marcelo H. Garcia (University of Illinois, U.S.A.) Suzanne J.M.H. Hulscher (University of Twente, NL) Stefano Lanzoni (Università di Padova, Italy) Miguel A. Losada (University of Granada, Spain) Chris Paola (University of Minnesota, U.S.A.) Gary Parker (University of Illinois U.S.A.) Luca Ridolfi(Politecnico di Torino, Italy) Andrea Rinaldo (École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne, Switzerland) Yasuyuki Shimizu (Hokkaido University, Japan) Marco Tubino (Università di Trento, Italy) Markus Uhlmann (Karlsruhe Institute of Technology, Germany) Introduction to Morphodynamics of Sedimentary Patterns Paolo Blondeaux, Marco Colombini, Giovanni Seminara, Giovanna Vittori Introduction to Morphodynamics of Sedimentary Patterns is the bookmark of the University of Genoa On the cover: The delta of Lena river (Russia). The image was taken on July 27, 2000 by the Landsat 7 satellite operated by the U.S. Geological Survey and NASA (false-color composite image made using shortwave infrared, infrared, and red wavelengths). Image credit: NASA This book has been object of a double peer-review according with UPI rules. Publisher GENOVA UNIVERSITY PRESS Piazza della Nunziata, 6 16124 Genova Tel. 010 20951558 Fax 010 20951552 e-mail: [email protected] e-mail: [email protected] http://gup.unige.it/ The authors are at disposal for any eventual rights about published images. -

How to Make a Meandering River

COMMENTARY How to make a meandering river Alan D. Howard1 Department of Environmental Sciences, P.O. Box 400123, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA 22904-4123 espite the ubiquity of mean- dering rivers in nature, only recently have appropriate ex- perimental conditions been Dproduced to replicate a stably meander- ing stream in the laboratory, as de- scribed in a recent issue of PNAS (1). Meandering channels occur in a wide variety of sedimentary environments, including on deep sea fans formed by turbidity currents (2), as relict meanders on Mars (3) (Fig. 1), and as channels formed by flowing alkenes on Titan. The mechanics of formation of mean- ders is reasonably well understood (4). When flow enters a channel bed, a heli- cal secondary current is set up that in- creases flow velocity and channel depth along the outer bank in proportion to bed curvature, which encourages bank erosion. The secondary current has an intrinsic downstream scale related to flow velocity and depth; this results in gradual increase in bend amplitude and propagation of the meandering pattern upstream and downstream. Linear the- ory of flow in bends (5) has permitted construction of simulation models that replicate many aspects of meandering Fig. 1. Fossil highly sinuous meandering channel and floodplain on Mars. Red arrows point to repre- behavior, including meander cutoffs, sentative locations along channel. The channel bed is now a ridge (in inverted relief) because wind erosion creation of oxbow lakes, and patterns of has removed finer sediment from the floodplain and surrounding terrain. The low curvilinear ridges floodplain sedimentation (6, 7). -

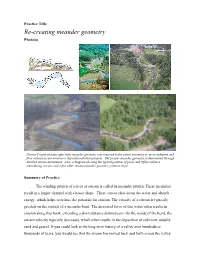

Re-Creating Meander Geometry Photo(S)

Practice Title Re-creating meander geometry Photo(s) Greene County streams after their meander geometry was restored to the extent necessary to move sediment and flow without excess erosion or deposition (bottom photos). The proper meander geometry is determined through detailed stream assessment. Also, a diagram showing the typical position of pools and riffles within a meandering stream, and a few other stream meander geometry patterns (top). Summary of Practice The winding pattern of a river or stream is called its meander pattern. These meanders result in a longer channel with a lower slope. These curves slow down the water and absorb energy, which helps to reduce the potential for erosion. The velocity of a stream is typically greatest on the outside of a meander bend. The increased force of this water often results in erosion along this bank, extending a short distance downstream. On the inside of the bend, the stream velocity typically decreases, which often results in the deposition of sediment, usually sand and gravel. If you could look at the long-term history of a valley over hundreds or thousands of years, you would see that the stream has moved back and forth across the valley bottom. In fact, this lateral migration of the channel, accompanied by down cutting, is what has formed the valley. Success in stream management is based on working with the stream, not against it. If a reach of channel is suffering unusual bank erosion, down cutting of the bed, aggradation, change of channel pattern, or other evidence of instability, a realistic approach to addressing these problems should be based on restoring the system’s equilibrium. -

6.6.4 Bank Angle and Channel Cross-Section

Section 6 Physical Habitat Characterization— Non-wadeable Rivers by Philip R. Kaufmann In the broad sense, physical habitat in ecology that are likely applicable in rivers as rivers includes all those physical attributes that well. They include: influence or provide sustenance to river or- • Channel Dimensions ganisms. Physical habitat varies naturally, as do biological characteristics; thus expectations • Channel Gradient differ even in the absence of anthropogenic disturbance. Within a given physiographic- • Channel Substrate Size and Type climatic region, river drainage area and chan- • Habitat Complexity and Cover nel gradient are likely to be strong natural determinants of many aspects of river habitat, • Riparian Vegetation Cover and Struc- because of their influence on discharge, flood ture stage, and stream power (the product of dis- charge times gradient). Summarizing the habi- • Anthropogenic Alterations tat results of a workshop conducted by EMAP • Channel-Riparian Interaction on stream monitoring design, Kaufmann (1993) identified seven general physical habi- All of these attributes may be directly or tat attributes important in influencing stream indirectly altered by anthropogenic activities. Nevertheless, their expected values tend to 1U.S. EPA, National Health and Environmental Effects Re- vary systematically with river size (drainage search Laboratory, Western Ecology Division, 200 SW 35th St., Corvallis, OR 97333. area) and overall gradient (as measured from 6-1 topographic maps). The relationships of spe- scales the sampling reach length and resolu- cific physical habitat measurements described tion in proportion to stream size. It also al- in this EMAP-SW field manual to these seven lows statistical and series analyses of the data attributes are discussed by Kaufmann (1993).