Download for the Reader

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Каталог Создан В Системе Zooportal.Pro 1 INTERNATIONAL DOG SHOW CACIB – FCI «BELYE NOCHI» ИНТЕРНАЦИОНАЛЬНАЯ ВЫСТАВКА СОБАК CACIB – FCI "БЕЛЫЕ НОЧИ"

Каталог создан в системе zooportal.pro 1 INTERNATIONAL DOG SHOW CACIB – FCI «BELYE NOCHI» ИНТЕРНАЦИОНАЛЬНАЯ ВЫСТАВКА СОБАК CACIB – FCI "БЕЛЫЕ НОЧИ" 24 октября 2020 г. ОРГАНИЗАТОР ВЫСТАВКИ: МОКО КЕННЕЛ-КЛУБ САНКТ-ПЕТЕРБУРГА 194044 Россия, Санкт-Петербург, Нейшлотский пер., дом 9 Почтовый адрес: 194044, Санкт-Петербург, Нейшлотский пер.,9 [email protected] +7 812 5420504 МЕСТО ПРОВЕДЕНИЯ: Конгрессно-выставочный центр «ЭКСПОФОРУМ». Россия, Санкт-Петербург, Шушары, Петербургское ш., 64/1 ОРГАНИЗАЦИОННЫЙ КОМИТЕТ ВЫСТАВКИ: Председатель оргкомитета Седых Н. Б. Члены оргкомитета Седых Н. Е., Расчихмаров А. П., Жеребцова А. А. Главный секретарь выставки Дегтярева Н. И. Руководитель пиар-службы Шапошникова М. В. Руководитель пресс-центра Блажнова В. Б. СТАЖЕРЫ: Раннамяги О., Котляр Н., Коваленко М., Алифиренко В., Кениг М. Для проведения экспертизы в экстерьерных рингах приглашены эксперты: Эксперт / Judge Ринг Георгий Баклушин / Georgiy Baklushin (Россия / Russia) 1 Душан Паунович / Dusan Paunovic (Сербия / Serbia) 2 Виктор Лобакин / Viktor Lobakin / (Азербайджан / Azerbaijan) 3 Павел Марголин / Pavel Margolin (Россия / Russia) 4 Алексей Белкин / Alexey Belkin (Россия / Russia) 5 Юлия Овсянникова / Yulia Ovsyannikova (Россия / Russia) 6 Елена Кулешова / Elena Kuleshova (Россия / Russia) 7 Зоя Богданова / Zoya Bogdanova (Россия / Russia) 8 Резервный эксперт / Reserve Judge: Наталья Никольская / Natalia Nikol’skaya (Россия / Russia) Каталог создан в системе zooportal.pro 2 Регламент работы выставки «БЕЛЫЕ НОЧИ» / Show’s «BELYE NOCHI» Operating -

Khanty-Mansiysk

Khanty-Mansiysk www.visithm.com Valery Gergiev, People’s Artist of Russia, the Artistic and General Director of the Mariinsky Theatre: «It is a very big fortune that in Khanty-Mansiysk with its 80,000 inhabitants (let it be 100,000 people as there are a lot of guests) there is such a cultural centre. Not every city with population exceeding one million can afford the same». Dmitry Guberniev, Russian sports commentator: «Khanty-Mansiysk is like home for me. I enjoy visiting it again and again. Furthermore, I have a lot of friends there». Elena Yakovleva, Russian film and stage actress, Honoured Artist of Russia, People’s Artist of Russia: «What I managed to see from the window of a car impressed me greatly. I really envy people who live there as they live in a fairy-tale. These are not just words and I am absolutely sincere. There is a taiga near the houses that attracts and invites to stay here a bit longer». Airport park А Immediately after your cheo landing in Khanty-Mansiysk Ar you can feel Siberian colour of the city. The international The cultural and tourist airport successfully combines complex “Archeopark”, national traditions and located at the base modern style: it is made of of the butte of the advanced materials in the ancient glacier, is one form of Khanty chum (raw- of the main sights of hide tent). the capital of Ugra. Its bronze inhabitants depict the way of life of the Paleolithic people and animals from the Pleistocene time. Almost all ancient animals are made in full size here, and you can make original photos with them. -

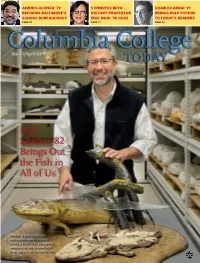

Neil Shubin '82 Brings out the Fish in All of Us

ANDRES ALONSO ’79 5 MINUTES WITH … CHARLES ARDAI ’91 REFORMS BALTIMORE’S HISTORY PROFESSOR BRINGS PULP FICTION SCHOOL BUREAUCRACY MAE NGAI ’98 GSAS TO TODAY’S READERS PAGE 22 PAGE 11 PAGE 24 Columbia College March/April 2011 TODAY Neil Shubin ’82 Brings Out the Fish in All of Us Shubin, a paleontologist and evolutionary biologist, co-led a team that discovered evidence of the pivotal shift from aquatic to terrestrial life. ust another J membership perk. Meet. Dine. Entertain. Join the Columbia Club and access state-of-the-art meeting rooms for your conferences and events. For more information or to apply, visit www.columbiaclub.org or call (212) 719-0380. The Columbia University Club of New York in residence at 15 West 43 St. New York, N Y 10036 Columbia’s SocialIntellectualCulturalRecreationalProfessional Resource in Midtown. Columbia College Today Contents 22 12 24 7 56 18 COVER STORY ALUMNI NEWS DEPARTMENTS G O FISH 27 O BITUARIES 2 LETTERS TO THE 12 Paleontologist and evolutionary biologist Neil Shubin 27 Joseph D. Coffee Jr. ’41 EDITOR ’82 brings out the fish in all of us. 28 Garland E. Wood ’65 3 ITHIN THE AMILY By Nathalie Alonso ’08 W F 30 B OOKSHEL F 4 AROUND THE QUADS FEATURES Featured: Adam Gidwitz ’04 4 turns classic folklore on its Northwest Corner Building Opens COLUMBIA FORUM ear with his new children’s 18 book, A Tale Dark & Grimm. 5 Rose, Jones Join In an excerpt from his book How Soccer Explains the College Senior Staff World: An Unlikely Theory of Globalization, Franklin 32 LASS OTES 6 Creed To Deliver Foer ’96 explains how one soccer club’s destiny was C N A LUMNI PRO F ILES Class Day Address shaped by European anti-Semitism. -

Global Social and Economic Challenges and Regional Development

NOVOSIBIRSK STATE UNIVERSITY OF ECONOMICS AND MANAGEMENT GLOBAL SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC CHALLENGES AND REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT Proceedings of the 16th International Conference of the Association of Economic Universities of South and Eastern Europe and the Black Sea Region (ASECU) (November 19, 2020) Novosibirsk, RUSSIA NOVOSIBIRSK STATE UNIVERSITY OF ECONOMICS AND MANAGEMENT (NSUEM) ASSOCIATION OF ECONOMIC UNIVERSITIES OF SOUTH AND EASTERN EUROPE AND THE BLACK SEA REGION (ASECU) GLOBAL SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC CHALLENGES AND REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT Proceedings of the 16th International Conference of the Association of Economic Universities of South and Eastern Europe and the Black Sea Region (ASECU) (November 19, 2020) Global Social and Economic Challenges and Regional Development : 16th International Conference of the Association of Economic Universities of South and Eastern Europe and the Black Sea Region (ASECU) (November 19, 2020). Novosibirsk : NSUEM, 2021. 272 p. ISBN 978-5-7014-0987-1 An author bears the full responsibility for the original ideas of their work as well as for the mistakes made solely by them. Editors: Grigorios Zarotiadis, Oleg Bodyagin, Leonid Nakov, Fatmir Memaj, Dejan Mikerevic, Pascal Zhelev, Vesna Karadzic, Zaklina Stojanovic, Bogdan Wierzbinski, Larisa Afanasyeva, Maria Krasnova © ASECU, 2021 ISBN 978-5-7014-0987-1 © NSUEM, 2021 INTERNATIONAL SCIENTIFIC COMMITTEE Aleksandr Novikov, Novosibirsk State University of Economics and Management, Russia Leonid Nakov, St. Cyril and Methodius University, Skopje, North Macedonia Grigoris -

Meat Tenderization Through Plant Proteases- a Mini Review

Int. J. Biosci. 2021 International Journal of Biosciences | IJB | ISSN: 2220-6655 (Print), 2222-5234 (Online) http://www.innspub.net Vol. 18, No. 1, p. 102-112, 2021 REVIEWPAPER OPEN ACCESS Meat Tenderization through Plant Proteases- A Mini Review Ali Ikram, Saadia Ambreen, Amber Tahseen, Areeg Azhar, Khadija Tariq, Tayyba Liaqat, Muhammad Babar Bin Zahid, Muhammad Abdul Rahim, Waseem Khalid*, Naqash Nasir Institute of Home and Food Sciences, Government College University Faisalabad, Pakistan Key words: Meat Tenderization, Proteases, Papain, Bromelain, Ficin. http://dx.doi.org/10.12692/ijb/18.1.102-112 Article published on January 20, 2021 Abstract The tenderness and quality of meat is very concerning for meat consumers. Meat tenderness relies on connective tissue, and muscle proteolytic ability. The use of various chemical tenders is the subject of the majority of research studies on the meat tenderness. However, there are certain drawbacks of these chemical tenders on one or the other sensory characteristics of meat. Few natural tenderizers may be used to counteract these adverse effects of chemical goods. Natural tenderizers are certain vegetables and fruits containing proteolytic enzymes that are responsible for rough meat tenderization. The use of exogenous proteases to enhance the tenderness of meat received tremendous interest in order to consistently produce meat tenderness as well as add value to low- grade cuts. The overview elaborates the sources, characteristics, and uses of plant proteases for the tenderization of meat. Furthermore, it highlights the impact of plant protease on the meat quality and effect on the meat proteins. Plant enzymes (including papain, ficin and bromelain) have been thoroughly studied as tenderizers for meat. -

Вестник Угроведения Bulletin of Ugric Studies Doi: 10.30624/2220-4156

Bulletin of Ugric Studies. Vol. 9, № 2. 2019. ISSN 2220-4156 (print) ISSN 2587-9766 (online) ВЕСТНИК УГРОВЕДЕНИЯ BULLETIN OF UGRIC STUDIES DOI: 10.30624/2220-4156 Научный журнал Scholarly journal зарегистрирован в Федеральной службе по надзору registered in the Federal Service for Supervision of в сфере связи, информационных технологий и массовых Telecommunications, Information Technology and Mass коммуникаций (РОСКОМНАДЗОР) Министерства Communications (ROSKOMNADZOR) of the Ministry связи и массовых коммуникаций Российской of Telecommunications and Mass Communications of Федерации. Запись в Реестре зарегистрированных Russian Federation, entry in the Register of the registered средств массовой информации ПИ № ФС 77-74811 от mass media PI № FS 77-74811 on January 11, 2019. 11 января 2019 года. Решением Президиума Высшей аттестационной The decision of the Presidium of the Higher attestation комиссии Минобрнауки России журнал включен в Commission of the Ministry of education and science перечень ведущих рецензируемых научных журналов of Russia the journal is included in the List of leading и изданий, в которых должны быть опубликованы reviewed scientific magazines end editions in which should основные результаты диссертаций на соискание be published the main results of these on competition of ученых степеней доктора и кандидата наук с 1 декабря scientific degrees of doctor and candidate of Sciences on 2015 года. December 1, 2015. Журнал индексируется и архивируется в: The journal is indexed and archived by: Russin Index Российском индексе научного цитирования (РИНЦ), of Scientific Citations, Scopus, Сyberleninka, ELS «Lan», Scopus, КиберЛенинка, ЭБС «Лань», Crossref, Crossref, ERIHPLUS, ResearchBib, Ulrichsweb. ERIHPLUS, ResearchBib, Ulrichsweb. Том 9, № 2. 2019 Vol. 9, no. 2. 2019 Материалы журнала доступны The journal's materials are available по лицензии Сreative Commons "Attribution" under license Сreative Commons "Attribution" ("Атрибуция") 4.0 Всемирная 4.0 Worldwide 201 Вестник угроведения. -

The Fire History in Pine Forests of the Plain Area In

Nature Conservation Research. Заповедная наука 2019. 4(Suppl.1): 21–34 https://dx.doi.org/10.24189/ncr.2019.033 THE FIRE HISTORY IN PINE FORESTS OF THE PLAIN AREA IN THE PECHORA-ILYCH NATURE BIOSPHERE RESERVE (RUSSIA) BEFORE 1942: POSSIBLE ANTHROPOGENIC CAUSES AND LONG-TERM EFFECTS Alexey А. Aleinikov Center for Forest Ecology and Productivity of RAS, Russia e-mail: [email protected] Received: 10.02.2019. Revised: 21.04.2019. Accepted: 23.04.2019. The assessment of the succession status and the forecast of the development of pine forests depend on their origin and need a detailed study of historical and modern fire regimes. This article summarises the information on the dynamics of fires in the forests of the plain area in the Pechora-Ilych Biosphere Reserve (Russia) before 1942. Current forest fires in the pine forests in the Pechora-Ilych Biosphere Reserve are a legacy of previous traditional land use on this territory. Thanks to the material analysis of the first forest inventory, the condition of the forests of the plain area was assessed for the first time 10 years after the foundation of the Pechora-Ilych Bio- sphere Reserve. It was shown that about 50% of the forests of the modern plain area (most of the lichen, green moss-lichen and green moss-shrub communities) at that time were already touched by ground and crown fires. The population got accustomed to the smoke along the tributaries of the Pechora and the Ilych rivers, so that they reflected it in the names. Perhaps, for several centuries, fires were initiated by the Mansi, who used this territory as winter pastures until the middle of the 19th century. -

Towards a Corpus-Based Grammar of Upper Lozva Mansi: Diachrony and Variation

Introduction Upper Lozva Mansi Our Documentation Grammar writing Conclusion Towards a corpus-based grammar of Upper Lozva Mansi: diachrony and variation Daria Zhornik, Sophie Pokrovskaya, Vladimir Plungian Lomonosov Moscow State University Institute of Linguistics, Russian Academy of Sciences [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Descriptive Grammars and Typology, Helsinki, 29.03.2019 . Daria Zhornik, Sophie Pokrovskaya, Vladimir Plungian MSU, ILing RAS Upper Lozva Mansi: diachrony and variation Introduction Upper Lozva Mansi Our Documentation Grammar writing Conclusion Overview Introduction Upper Lozva Mansi Our Documentation Grammar writing Conclusion . Daria Zhornik, Sophie Pokrovskaya, Vladimir Plungian MSU, ILing RAS Upper Lozva Mansi: diachrony and variation Introduction Upper Lozva Mansi Our Documentation Grammar writing Conclusion Some background I Mansi < Ob-Ugric < Uralic, EGIDS status: threatened; I Russia, 940 speakers (2010 census) in Western Siberia. Daria Zhornik, Sophie Pokrovskaya, Vladimir Plungian MSU, ILing RAS Upper Lozva Mansi: diachrony and variation Introduction Upper Lozva Mansi Our Documentation Grammar writing Conclusion The Mansi language I Earlier: 4 Mansi dialect branches I Today: only the Northern group survives I Most Northern Mansi speakers: disperse distribution in the Khanty-Mansi Autonomous Okrug I Speakers mostly live in Russian villages/towns: I forced shift to Russian; I almost no opportunities for using Mansi; I all education is in Russian I In turns out that much -

Specific Character of Modern Interethnic Relations in Krasnoyarsk Territory As Per Associative Experiment

Journal of Siberian Federal University. Humanities & Social Sciences 11 (2011 4) 1553-1576 ~ ~ ~ УДК 316.622 Specific Character of Modern Interethnic Relations in Krasnoyarsk Territory as Per Associative Experiment Galina V. Kivkutsan* Siberian Federal University 79 Svobodny, Krasnoyarsk, 660041 Russia 1 Received 15.03.2011, received in revised form 17.06.2011, accepted 10.10.2011 Ethnocultural space of Krasnoyarsk territory is an urgent subject for research nowadays. According to the criteria of conflict, ethnology and sociology theory Krasnoyarsk territory has been both a centre of strained interethnic relations and a specific interethnic conglomerate. Thus, the study of ethnicity phenomenon in Krasnoyarsk territory is one of the most important tasks of applied cultural research. The research objectives are to detect an interethnic relations dominant type on the basis of specificity of ethnocultural space of Krasnoyarsk territory (while applying associative experiment method) and to model possible ways of conflict settlement. The research has resulted in the relevant conclusion that interethnic relations in the territory have a set of features peculiar to this territory. That has led to a hypothesis about a possible interethnic conflicts settlement in case of their threat. The research uniqueness is stated through both a particular practical orientation of the research and experimental application of new forms of the developed methods into the sphere of cultural research. A considerable attention has been paid to a complex approach to a definite problem. Associative experiment is considered to be the most effective method of detection and research of such a cultural phenomenon as ethnic stereotype. It is proved by the specificity of the method initially applied in psychology. -

3 Days Markhor Spotting Tour –

3 Days Markhor spotting tour – promotional November 2021 TRIP OVERVIEW Style: Hiking / Wildlife watching Difficulty: Level 3-4 Location: Darvoz & Shurobod region Driving distance: 600 km / 373mi Tour length: 3 days Departure: November 13, 2020 PRICES: 1 person – 310$ 2 people – 200$ per person 3 people – 185$ per person 4 people – 185$ per person 5 people – 167$ per person 6 people – 155$ per person Price includes: All meals-2 breakfasts, 3 lunches, 2 dinners | Transportation from and to Dushanbe with 4WD vehicles | An English speaking guide | Conservancy rangers services | Camping equipment – tents, utensils, stove etc. | Binoculars and Watching scopes Close HIGHLIGHTS: Spotting and observing endangered Markhor goats, Bird watching, Spectacular views of Hazratishoh mountains, Traditional Tajik village hospitality. DESCRIPTION: The Markhor is the largest species of goat family and is famous for its stunning twisting horns. Markhor is usually found in mountainous parts of Central Asia. Markhor habitat consists of dry mountains with cliffs. They graze in areas with sparse forest and many wooded shrubs. We offer3 days Markhor watching and photography in Shurobod region with departure from Dushanbe. The best time to see Markhor goats is in winter and early spring. You will also be able to see other wildlife on this tour like wild Boars, Ibex and many birds. Our guides have vast experience observing and studying Markhor and other wildlife. They will make sure you have fun, take lots of pictures, observe different age groups, and experience the culture and hospitality of conservancy families. We offer Markhor tours all year round. In the summer, however, they are more difficult to reach, as they tend to go up to an altitude of above 2500-3500 m (8200-11,482 feet), hence the tour should be prolonged. -

Sakha Cultural Festival Wednesday, June 18 Thru Sunday, June 22

Gualala Arts Global Harmony Season of Offerings Sakha Cultural Festival Wednesday, June 18 thru Sunday, June 22 Poland and New York. Examples of his art can be seen at the Sakha Culture exhibit. The same evening a performance art selection will showcase this intriguing culture. The Yakut people are the largest ethnic group in the Sakha Republic, a state with a population of almost a million people. It is located in eastern Siberia and spans three time zones. The Yakut share a story remarkably similar to the local Pomo in California. The discovery of gold and the building of the Trans- Siberia Railway brought ever-increasing numbers of Russians to their isolated region. Persecution by the Soviet government in the 1920s reduced their numbers to one-half of the current population, but they now form the federation’s majority population and are experiencing a revival of their culture. The festival continues through Sunday, June 22, with classes in jewelry, wood carving, and other Yakut crafts at Gualala Arts Center and at Fort Ross. Dinners at both venues will feature The 2014 Global Harmony Season of Sakha cuisine. Also, there will be talks on the role Yakut played Offerings culminates with a week-long at Fort Ross, on their spiritual beliefs, and the lifestyle and festival on the Mendonoma coast with cultural revival of indigenous people. activities at Gualala Arts Center, Fort Ross and the Gualala Point Regional Park. On Sunday, the festival concludes with a sunrise greeting at Gualala Point Regional Park, including traditional rituals and The scheduled events further strengthen dances. -

Racism, Discrimination and Fight Against “Extremism” in Contemporary Russia

RACISM, DISCRIMINATION and FIGHT AGAINSt “EXTREMISm” IN CONTEMPORARY RUSSIA Alternative Report on the Implementation of the UN Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination By the Russian Federation For the 93rd Session of the UN CERD July 31 – August 11, 2017 Racism, Discrimination and fight against “extremism” in contemporary Russia. Alternative Report on the Implementation of the UN Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination By the Russian Federation. For the 93rd Session of the UN CERD. July 31 – August 11, 2017. INDEX INTRODUCTION . 4 RACIALLY MOTIVATED VIOLENCE . 6 Hate crimes . 6 Reaction of the authorities to xenophobic speech . 7 Combating online incitement to hatred . 7 Federal list of extremist materials . 9 Definition of “extremist activities” . 9 DiSCRIMINATION IN CRIMEA . 12 Racial discrimination against Crimean Tatars in Crimea . 12 Restrictions on the operating of national institutions and systematic violation of civil and political rights . 12 Barriers to studying and using the Crimean Tatar language . 14 Freedom of religion and access to religious and culture sites . 15 State propaganda and incitement of ethnic strife . 18 Discrimination against Ukrainians . 21 Studying and using the Ukrainian language . 24 Holding of cultural events . 26 DiSCRIMINATION AGAINST MIGRANTS FROM REGIONS OF THE CAUCASUS TO RUSSIA (in the example of cities in western Siberia) . 28 Restrictions during the hiring process, lower salaries, and the glass ceiling in the public sector and at large corporations . 29 Problems with registration, renting housing, and conscription . 31 Increased attention from law enforcement authorities . Discriminatory and accusatory rhetoric in the media and society . 32 Nationalist organizations and their initial support from the government .