Global Social and Economic Challenges and Regional Development

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Каталог Создан В Системе Zooportal.Pro 1 INTERNATIONAL DOG SHOW CACIB – FCI «BELYE NOCHI» ИНТЕРНАЦИОНАЛЬНАЯ ВЫСТАВКА СОБАК CACIB – FCI "БЕЛЫЕ НОЧИ"

Каталог создан в системе zooportal.pro 1 INTERNATIONAL DOG SHOW CACIB – FCI «BELYE NOCHI» ИНТЕРНАЦИОНАЛЬНАЯ ВЫСТАВКА СОБАК CACIB – FCI "БЕЛЫЕ НОЧИ" 24 октября 2020 г. ОРГАНИЗАТОР ВЫСТАВКИ: МОКО КЕННЕЛ-КЛУБ САНКТ-ПЕТЕРБУРГА 194044 Россия, Санкт-Петербург, Нейшлотский пер., дом 9 Почтовый адрес: 194044, Санкт-Петербург, Нейшлотский пер.,9 [email protected] +7 812 5420504 МЕСТО ПРОВЕДЕНИЯ: Конгрессно-выставочный центр «ЭКСПОФОРУМ». Россия, Санкт-Петербург, Шушары, Петербургское ш., 64/1 ОРГАНИЗАЦИОННЫЙ КОМИТЕТ ВЫСТАВКИ: Председатель оргкомитета Седых Н. Б. Члены оргкомитета Седых Н. Е., Расчихмаров А. П., Жеребцова А. А. Главный секретарь выставки Дегтярева Н. И. Руководитель пиар-службы Шапошникова М. В. Руководитель пресс-центра Блажнова В. Б. СТАЖЕРЫ: Раннамяги О., Котляр Н., Коваленко М., Алифиренко В., Кениг М. Для проведения экспертизы в экстерьерных рингах приглашены эксперты: Эксперт / Judge Ринг Георгий Баклушин / Georgiy Baklushin (Россия / Russia) 1 Душан Паунович / Dusan Paunovic (Сербия / Serbia) 2 Виктор Лобакин / Viktor Lobakin / (Азербайджан / Azerbaijan) 3 Павел Марголин / Pavel Margolin (Россия / Russia) 4 Алексей Белкин / Alexey Belkin (Россия / Russia) 5 Юлия Овсянникова / Yulia Ovsyannikova (Россия / Russia) 6 Елена Кулешова / Elena Kuleshova (Россия / Russia) 7 Зоя Богданова / Zoya Bogdanova (Россия / Russia) 8 Резервный эксперт / Reserve Judge: Наталья Никольская / Natalia Nikol’skaya (Россия / Russia) Каталог создан в системе zooportal.pro 2 Регламент работы выставки «БЕЛЫЕ НОЧИ» / Show’s «BELYE NOCHI» Operating -

Pib's Daily Bulletin on Covid-19

8/6/2020 Press Information Bureau PIB Headquarters PIB’S DAILY BULLETIN ON COVID-19 Posted On: 06 AUG 2020 6:25PM by PIB Delhi (Contains Press releases concerning Covid-19, issued in last 24 hours, inputs from PIB Field Offices and Fact checks undertaken by PIB) Press Information Bureau Ministry of Information and Broadcasting Government of India https://pib.gov.in/PressReleseDetail.aspx?PRID=1643542 1/9 8/6/2020 Press Information Bureau India’s COVID-19 Recovery Rate climbs to 67.62%, as total recoveries cross 13.2 lakh; Case Fatality Rate (CFR) continues to slide, improves to 2.07% The total recoveries of COVID-19 patients have jumped to 13,28,336 with 46,121 COVID-19 patients being discharged in the last 24 hours. With such consistent increase in recoveries, the gap between recovered patients and active COVID-19 cases has reached 7,32,835.The recovery rate has continued its https://pib.gov.in/PressReleseDetail.aspx?PRID=1643542 2/9 8/6/2020 Press Information Bureau upward journey to reach another record high of 67.62% amongst COVID-19 patients.The actual case load of the country is the active cases (5,95,501) which is 30.31% of the total positive cases. They are under medical supervision either in hospitals or in home isolation.The active cases as a percentage of total cases have seen a significant drop from 34.17% on 24th July 2020 to 30.31% as on today.Case Fatality Rate (CFR) has been low when compared to the global scenario and it has been progressively falling. -

Updated Channel List

Brief Details of DD Free Dish channels as on 07.12.2020 Satellite GSAT- 15, 93.5 E TS-1 TS-2 TS-3 TS-4 TS-5 TS-6 Freq (MHz) Freq (MHz) Freq (MHz) Freq (MHz) Freq (MHz) Freq (MHz) U/L-14140 U/L-14220 U/L-14270 U/L-14310 U/L-14350 U/L-14430 D/L - 11090,Pol.-V D/L -11170, Pol.-V D/L- 11470, Pol.-V D/L- 11510, Pol.-V D/L- 11550, Pol.-V D/L -11630, Pol.-V S.R. -29.5 MSps, S.R. - 29.5 MSps, S.R.- 29.5 MSps, S.R.- 29.5 MSps, S.R.- 29.5 MSps, S.R.- 30MSps, FEC - 3/4 FEC - 3/4 FEC - 3/4 FEC - 3/4 FEC - 3/4 FEC - 3/5 CHANNELS (As per MPEG 4 set top box decoding) 1. DD-News 19. ABZY Dhakad 37. Sony Pal 55. Big Magic 73. Manoranjan 89. Home Channel Movies 2. DD National 20. DD Oriya 38. Rishtey 56. News 18 74. Test 502 90. Chardikala Time TV Cineplex India 3. DD Retro 21. DD Podhigai 39. Movie Plus 57. 9XM 75. Sadhna Bhakti 91. DD Goa 4. DD Kisan 22. DD Punjabi 40. DD 58. Maha Movie 76 . DD Rajasthan 92. DD Haryana Saptagiri 5. Zee Anmol 23. DD Sahyadri 41. Colors Rishtey 59. Zee Hindustan 77. DD Sports 93. DD Himachal Pradesh 6. DD Bangla 24. DD Yadagiri 42. B4U Kadak 60. DD Bharati 78. DD Bihar 94. Samay 105. BTV World 7. DD Chandana 25. -

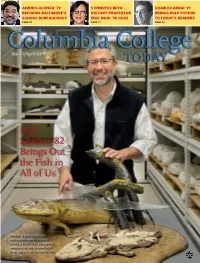

Neil Shubin '82 Brings out the Fish in All of Us

ANDRES ALONSO ’79 5 MINUTES WITH … CHARLES ARDAI ’91 REFORMS BALTIMORE’S HISTORY PROFESSOR BRINGS PULP FICTION SCHOOL BUREAUCRACY MAE NGAI ’98 GSAS TO TODAY’S READERS PAGE 22 PAGE 11 PAGE 24 Columbia College March/April 2011 TODAY Neil Shubin ’82 Brings Out the Fish in All of Us Shubin, a paleontologist and evolutionary biologist, co-led a team that discovered evidence of the pivotal shift from aquatic to terrestrial life. ust another J membership perk. Meet. Dine. Entertain. Join the Columbia Club and access state-of-the-art meeting rooms for your conferences and events. For more information or to apply, visit www.columbiaclub.org or call (212) 719-0380. The Columbia University Club of New York in residence at 15 West 43 St. New York, N Y 10036 Columbia’s SocialIntellectualCulturalRecreationalProfessional Resource in Midtown. Columbia College Today Contents 22 12 24 7 56 18 COVER STORY ALUMNI NEWS DEPARTMENTS G O FISH 27 O BITUARIES 2 LETTERS TO THE 12 Paleontologist and evolutionary biologist Neil Shubin 27 Joseph D. Coffee Jr. ’41 EDITOR ’82 brings out the fish in all of us. 28 Garland E. Wood ’65 3 ITHIN THE AMILY By Nathalie Alonso ’08 W F 30 B OOKSHEL F 4 AROUND THE QUADS FEATURES Featured: Adam Gidwitz ’04 4 turns classic folklore on its Northwest Corner Building Opens COLUMBIA FORUM ear with his new children’s 18 book, A Tale Dark & Grimm. 5 Rose, Jones Join In an excerpt from his book How Soccer Explains the College Senior Staff World: An Unlikely Theory of Globalization, Franklin 32 LASS OTES 6 Creed To Deliver Foer ’96 explains how one soccer club’s destiny was C N A LUMNI PRO F ILES Class Day Address shaped by European anti-Semitism. -

Registered Msos As on 03.08.2020 S.No

Registered MSOs as on 03.08.2020 S.No. Name of MSO Address for Correspondence State Type of Entity Registration No. Date of issue Registation Phone No. Email Remarks of Valid Registration Upto (DD/M M/YYYY) 1 5 Star Network Surpura Road, Bahel Haryana Proprietorship 9/240/2016-DAS 31-10-2016 30-10-2026 98122 45678 5starnetworkbehal@gmail. Bhiwani – 127028 com 2 9 Star Digital Cable D.No. 15-195, Karampudi Road, Andhra Pradesh Partnership 9/109/2015-DAS 24-06-2016 23-06-2026 98483 18777 Palnadu.communications@ Network Gurazala gmail.com Dist. Guntur – 522415 3 A B C O Plot No.6, Ashok Nagar , Odisha Partnership 9/97/2016-DAS 17-05-2016 16-05-2026 98614 44555 [email protected] Bhubaneswar Opp. State Bank of Hyderabad, District Khurda – 751009 4 A Boss Digital System Murugandha Bhavanam, Tamil Nadu Proprietorship 9/491/2015-DAS 17-05-2016 16-05-2026 98421 66931 [email protected] 14-C AA Road Madurai – 625016 5 A– Vision Channel Vrindavan Colony Chhattisgarh Proprietorship 9/77/2016-DAS 26-02-2016 25-02-2026 94252 58909 [email protected] Jagdalpur District m Bastar – 494001 6 A.C.N Cable Pvt. Ltd. Trade Center, No. 29/4, Karnataka Company 9/44/2013-BP&L 21-07-2015 20-07-2025 80428 84888 [email protected] 4th Floor, Race Course Road, 95380 67831 [email protected] Banglore – 560001 080 4288-4288 7 Aadhar Digital Vision Pvt. 37/19, Ayalur Muthiah Street, Tamil Nadu Company 9/56/2012-BP&L 21-02-2014 20-02-2024 98409 03060 [email protected] Ltd Kondithope, Chennai - 600079 94449 99763 [email protected] 8 Aadhishakti Digital Plot No. -

Pib's Daily Bulletin on Covid-19

9/1/2020 Press Information Bureau PIB Headquarters PIB’S DAILY BULLETIN ON COVID-19 Posted On: 31 AUG 2020 6:27PM by PIB Delhi (Contains Press releases concerning Covid-19, issued in last 24 hours, inputs from PIB Field Offices and Fact checks undertaken by PIB) https://pib.gov.in/PressReleseDetail.aspx?PRID=1650053 1/10 9/1/2020 Press Information Bureau On a steep rise, India conducts more than 4.23 cr tests, 43% of Total Cases recorded in just 3 States-Maharashtra, AP, Karnataka Starting from a single test in one lab in Pune in January 20202, the daily testing capacity has been scaled up to more than 10 lakh in August 2020. The cumulative tests have crossed 4.23 cr today. 8,46,278 tests were conducted in the past 24 hours. India has registered 78,512 cases in the last 24 hours (Sunday, 30th August 2020). Hence the report by certain Media Entities of about 80,000 cases in the last 24 hours is without any basis. Seven States have contributed to 70% of these new cases in https://pib.gov.in/PressReleseDetail.aspx?PRID=1650053 2/10 9/1/2020 Press Information Bureau the last 24 hours. Of these, Maharashtra has contributed the maximum case load amounting to almost 21%, followed by Andhra Pradesh (13.5%), Karnataka (11.27%) and Tamil Nadu which stands at 8.27%. Uttar Pradesh with 8.27%, West Bengal with 3.85%, and Odisha with 3.84% are the remaining States contributing to the increased caseload. Of the total cumulative number of cases, 43% are recorded in just three states of Maharashtra, Andhra Pradesh and Karnataka. -

List of TV Channels Avai Channels Available on DD Free Dish

List of TV Channels available on DD Free Dish GENERAL ENTERTAINMENT CHANNEL(GEC) DD NATIONAL DD BHARATI DD URDU DD KISAN DD RETRO DANGAL BIG MAGIC ABZY COOL SHEMAROO TV SONY PAL STAR UTSAV COLORS RISHTEY ZEE ANMOL MOVIES(HINDI) MOVIE PLUS MAHA MOVIES B4U MOVIES MANORANJAN TV B4U KADAK ABZY MOVIES ENTERR10 MOVIES SURYA CINEMA DHINCHAAK RISHTEY CINEPLEX ZEE ANMOL CINEMA ABZY DHAKAD STAR UTSAV MOVIES SONY WAH MUSIC B4U MUSIC ZING MTV BEATS MASTIII 9XM NEWS DD NEWS LOK SABHA TV RAJYA SABHA TV DD INDIA NDTV INDIA REPUBLIC TV BHARAT ZEE NEWS ABP NEWS AAJ TAK TEZ News 18 INDIA INDIA TV NEWS 24 NEWS NATION ZEE HINDUSTAN TV9 BHARATVARSH SAMAY SUDARSHAN NEWS ARYAN TV NATIONAL NEWS STATE UP/UK LIVE TODAY VIP NEWS ANB NEWS NEWS INDIA 24X7 JANTANTRA TV SPORTS CHANNELS DD SPORTS REGIONAL CHANNELS DD RAJASTHAN DD ORIYA DD PODHIGAI DD PUNJABI DD SAHYADRI DD YADAGIRI DD MALAYALAM DD BIHAR DD NORTH-EAST DD UP DD SAPTGIRI DD MP DD ARUNPRABHA DD BANGLA DD CHANDANA DD GIRNAR DD KASHIR MANORANJAN FAKT MARATHI ZEE PUNJABI SHEMAROO MAHA PUNJABU CHARDIKLA TIME TV POPULAR TV MOVIES MARATHIBANA BHOJPURI B4U BHOJPURI BIG GANGA DABANGG BHOJPURI CINEMA ZEE BISKOPE SURYA BHOJPURI FILAMCHI DEVOTIONAL AASTHA SANSKAR SADHNA BHAKTI LORD BUDDHA SATSANG VEDIC HD CHANNELS DD NEWS DD STATE CHANNELS DD MANIPUR DD MEGHALAYA DD MIZORAM DD TRIPURA DD NAGALAND DD HARYANA DD JHARKHAND DD HIMACHAL DD DD RAIPUR DD GOA PRADESH UTTARAKHAND FOREIGN CHANNELS BTV KBS CO-BRANDED CHANNEL DD SWYAM Prabha 1-22 DD eVidya 1-12 DD Vande Gujarat 1-16 DD DigiShala Genre wise list of DD Free Dish Channels S. -

Growing Together Articulates a Number of Proposals That Can Help the Region Exploit Its Huge Untapped Potential for Regional Economic Integration

i Photo by Warren Field ii FOREWORD For the global economy, these are difficult times. The world is emerging from a crisis whose aftershocks continue to resonate – trapping some of the richest economies in recession and shaking the foundations of one of the world’s major currencies. Here at ESCAP, there are historical echoes. What is now the Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific was founded more than 60 years ago – also in the aftermath of a global crisis. The countries of Asia and the Pacific established their new Commission partly to assist them in rebuilding their economies as they came out of the yoke of colonialism and the Second World War. The newly established ECAFE, as ESCAP was called then, held a ministerial conference on regional economic cooperation in 1963 that resolved to set up the Asian Development Bank with the aim of assisting the countries in the region in rebuilding their economies. Fifty years later, the Asia-Pacific region is again at a crossroads, on this occasion seeking ways and means to sustain its dynamism in a dramatically changed global context in the aftermath of a global financial and economic crisis. An important change is the fact that, burdened by huge debts and global imbalances, the advanced economies of the West are no longer able to play the role of engines of growth for the Asia-Pacific region that they played in the past. Hence, the Asia-Pacific region has to look for new engines of growth. The secretariat of ESCAP has argued over the past few years that regional developmental challenges, such as poverty and wide disparities in social and physical infrastructure, can be turned into opportunities for sustaining growth in the future. -

Scat India 2020 - We Go Digital Edition Sets a New Benchmark Telebreeze & Kings Broadband Build on an Ambitious Partnership

RNI No. 57078/1993. Postal Registration No. MCS/225/2019-21. License to Post Without Prepayment; WPP License No. MR/Tech/WPP/South/351/2019-21. Published on the 10th of every month.Posted on the 11th & 12th of every month at Mumbai Patrika Channel Sorting Office Mumbai 400001. Total 68 Pages NOVEMBER 2020 ` 100 SATELLITE & CABLE TV TRADE GUIDE SATELLITE NOVEMBER 2020 TRADE GUIDE OFFICIAL PUBLICATION VOL XXVIII / 9 / 2020 27 …….including Broadband & IPTV NOVEMBER 2020 SCAT INDIA 2020 - WE GO DIGITAL EDITION SETS A NEW BENCHMARK TELEBREEZE & KINGS BROADBAND BUILD ON AN AMBITIOUS PARTNERSHIP VOLUME XXVIII / 9 2020 INDIA’S NEW SPACE COMMUNICATION POLICY INDIA - SIXTH LARGEST OTT MARKET WALT DISNEY REJIGS MEDIA STRATEGY OTT NEWS …. BROADBAND .... DISH DOCTOR …. CHANNEL GUIDE .... AND LOTS MORE….!! INDIA’S MOST RESPECTED TRADE MAGAZINE FOR THE CABLE TV, BROADBAND, IPTV & SATELLITE INDUSTRY Education .. Made In SET TOP BOX BIS APPROVED Cable TV STB IPTV/ OTT/ANDROID CH+ CH- VOL+ VOL- POWER Satellite STB S/S2 CHAMPION EMCS- 4000SG TM CHAMPION 2000 IPTV/ OTT STB MCBS WINS STB INNOVATION AWARD MPEG-4 HD, SD, MPEG-2 Hybrid HD (Cable+IPTV) Android/GSM STB Now Now designdesign youryour ownown STBSTB asas perper customizedcustomized requirementrequirement IndianIndian STBSTB DesignDesign househouse forfor youryour STBSTB needsneeds INDIA’S LARGEST SELLING DIGITAL HEADEND SYSTEM CONVERGENCE HEADEND A Complete Solution For Cable, Satelite, Mobile & IPTV INTEGRATE InstalledInstalled basebase ofof IPTV / WEB TV / MOB TV / OTT WITH COMMON WEALTH CABLE NETWORK AND MCBSMCBS HeadendsHeadends GAMES 2010 BECOME NEXTGEN OPERATOR Already installed by manymany telecomtelecom operatorsoperators Analog Headends 20,000+ && MSO’sMSO’s inin IndiaIndia likelike JIOJIO !! ANDROID Digital Headends 3000+ Flash Streaming Super Headends 35+ Encoders 65,000+ HITS HEADENDS PRODUCTS MCBS has set up an ultra modern state-of-the-art Surface Mount Technology (SMT) plant, incorporating world's most renowned robotic machineries. -

Санкт-Петербург / Saint-Petersburg 4 Мая 2019 Года / May 4, 2019

САНКТ-ПЕТЕРБУРГ / SAINT-PETERSBURG 4 МАЯ 2019 ГОДА / MAY 4, 2019 Организатор: СПБ РОО Кинологический Клуб «Элита» Saint-Petersburg Elite Kennel club ОАНКОО 2 САНКТ-ПЕТЕРБУРГ /SAINT-PETERSBURG 4 МАЯ 2019 ГОДА / MAY 4, 2019 Организатор: СПБ РОО Кинологический Клуб «Элита» Saint-Petersburg Elite Kennel club ОАНКОО 3 Организатор: СПБ РОО Кинологический Клуб «Элита» 199178, Санкт-Петербург, 11-я линия В.О., 24 [email protected] тел. +7 812 326 0291 Elite Kennel Club 11-th Line, 24 Saint-Petersburg, Russia 199178 [email protected] tel. +7 812 326 0291 Место проведения: КОНГРЕССНО-ВЫСТАВОЧНЫЙ ЦЕНТР "ЭКСПОФОРУМ", ПАВИЛЬОН F Санкт-Петербург, п. Шушары., Петербургское ш., дом 64/1 Peterburgskoye Shosse, 64, St Petersburg Оргкомитет: Резцов В.В., Лобова Ю.Б., Халуторных К.И., Дубровина Т.Б. Judges / Судьи: Anatoli Zhuk (Belorussia) / Анатолий Жук (Беларусь) Anita Foley-Duggan (Ireland) / Анита Фолей-Дугган (Ирландия) Bruno Nodalli (Italy) / Бруно Нодалли (Италия) Charlotta Mellin (Sweden) / Шарлотта Меллин (Швеция) Ety Goor (Israel) / Эти Гор (Израиль) Hans Almgren (Sweden) / Ханс Альмгрен (Швеция) Ivo Ingraffia (Italy) / Иво Инграффиа (Италия) Kristina Vanickova (Czech Republic) / Кристина Ваничкова (Чехия) Nenad Matejevic (Serbia) / Ненад Матеевич (Сербия) Nina Kharatishvili (Russia) / Нина Харатишвили (Россия) Maria Amelia Taborda (Portugal) / Мария Амелия Таборда (Португалия) Mariano Di Chicсo (Italy) / Мариано Ди Чикко (Италия) Olga Kosareva (Russia) / Ольга Косарева (Россия) Ramon Podesta (Chili) / Рамон Подеста (Чили) Sharon Sakson (USA) / Шэрон Сэксон (США) Shamil Abrakimov (Russia) / Шамиль Абракимов (Россия) Vladimir Aleksandrov (Russia) / Владимир Александров (Россия) Yochai Barak Lifac (Israel) / Йохай Барак Лифац (Израиль) Резервный судья: Yulia Pokrovskaya (Russia) / Юлия Покровская (Россия) Стажеры в рингах: А.Логинова, О.К. -

Current Affairs August 2020 Date – 5 August 2020 Alternative Academic Calendar for Upper Primary Stage Students

Current Affairs 2020 Current Affairs August 2020 Date – 5 August 2020 Alternative Academic Calendar for upper primary stage students Union Education Minister Ramesh Pokhriyal Nishank released the Alternative Academic Calendar for upper primary stage students. NCERT under the guidance of Education Ministry has developed the alternative academic calendars for students, parents and teachers of primary and upper primary stages with an aim to engage students meaningfully during their stay at home due to COVID-19. The Calendar provides guidelines to teachers on the use of various technological tools and social media tools available for imparting education in fun-filled and interesting ways. This calendar will cater to the need of all children including Divyang children (Children with Special Need) as link for Audio books, Radio programmes, Video programme will be included. World Breastfeeding Week 2020 World Breastfeeding Week (WBW) is a global campaign to raise awareness and galvanise action on themes related to breastfeeding. The 2020 theme is “Support breastfeeding for a healthier planet.” It is an annual celebration which is held every year from 1 to 7 August in more than 120 countries. Being organized by WABA, WHO and UNICEF, WBW came up with the goal to promote exclusive breastfeeding for the first six months of life which yields many health benefits, providing critical nutrients, protection from deadly diseases such as pneumonia and fostering growth and development for the first time in 1991. The correct norms of infant and young child feeding are: Initiation of Breastfeeding within an hour of birth. Exclusive breastfeeding for first six months of life i.e. -

Tiertus Romane: an Examination of Mystical Political Theology in Muscovite Russia

TIERTUS ROMANE: AN EXAMINATION OF MYSTICAL POLITICAL THEOLOGY IN MUSCOVITE RUSSIA A Thesis by EVAN WALLACE Submitted to the Graduate School at Appalachian State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS May 2018 Department of History TIERTUS ROMANE: AN EXAMINATION OF MYSTICAL POLITICAL THEOLOGY IN MUSCOVITE RUSSIA A Thesis by EVAN WALLACE May 2018 APPROVED BY: Anatoly Isaenko, Ph.D. Chairperson, Thesis Committee Jason White, Ph.D. Member, Thesis Committee Ralph Lentz II, M.A. Member, Thesis Committee Dr. James Goff Chairperson, Department of History Max C. Poole, Ph.D. Dean, Cratis D. Williams School of Graduate Studies Copyright by Evan Wallace 2018 All Rights Reserved Abstract TIERTUS ROMANE: AN EXAMINATION OF MYSTICAL POLITICAL THEOLOGY IN MUSCOVITE RUSSIA Evan Wallace B.A., University of Central Florida M.A., Appalachian State University Chairperson: Dr. Anatoly Isaenko The relationship between the Russian Orthodox Church and Russian state has received less than required academic attention. In the post-Soviet space, the Russian Church has again begun to interact with the Russian state. Through research of Russian primary sources including chronicles, vitae of princes, and various correspondence, this paper traces the origins of the relationship between Church and State and examines both the mystical and political theological actualities of such. This thesis demonstrates similarities, historical themes, and aspects of Church and State interactions through a comparison to Ernst Kantorowicz’s The King’s Two Bodies: A Study in Mediaeval Political Theology that can be applied to examine modern day Russian Church and State political theology. Ultimately the notion laid out by modern political theorists such as Carl Schmitt that the state has secularized theological themes is partially disproven by a case study of Russian history.