Abd Al Malik's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Liste CD Vinyle Promo Rap Hip Hop RNB Reggae DJ 90S 2000… HIP HOP MUSIC MUSEUM CONTACTEZ MOI [email protected] LOT POSSIBLE / NEGOCIABLE 2 ACHETES = 1 OFFERT

1 Liste CD Vinyle Promo Rap Hip Hop RNB Reggae DJ 90S 2000… HIP HOP MUSIC MUSEUM CONTACTEZ MOI [email protected] LOT POSSIBLE / NEGOCIABLE 2 ACHETES = 1 OFFERT Type Prix Nom de l’artiste Nom de l’album de Genre Année Etat Qté média 2Bal 2Neg 3X plus efficacae CD Rap Fr 1996 2 6,80 2pac How do u want it CD Single Hip Hop 1996 1 5,50 2pac Until the end of time CD Single Hip Hop 2001 1 1,30 2pac Until the end of time CD Hip Hop 2001 1 5,99 2 Pac Part 1 THUG CD Digi Hip Hop 2007 1 12 3 eme type Ovnipresent CD Rap Fr 1999 1 20 11’30 contre les lois CD Maxi Rap Fr 1997 1 2,99 racists 44 coups La compil 100% rap nantais CD Rap Fr 1 15 45 Scientific CD Rap Fr 2001 1 14 50 Cent Get Rich or Die Trying CD Hip Hop 2003 1 2,90 50 CENT The new breed CD DVD Hip Hop 2003 1 6 50 Cent The Massacre CD Hip Hop 2005 2 1,90 50 Cent The Massacre CD dvd Hip Hop 2005 1 7,99 50 Cent Curtis CD Hip Hop 2007 1 3,50 50 Cent After Curtis CD Diggi Hip Hop 2007 1 5 50 Cent Self District CD Hip Hop 2009 1 3,50 100% Ragga Dj Ewone CD 2005 1 5 Reggaetton 113 Prince de la ville CD Rap Fr 2000 2 4,99 113 Jackpotes 2000 CD Single Rap Fr 2000 1 3,80 2 113 Tonton du bled CD Rap Fr 2000 1 0,99 113 Dans l’urgence CD Rap Fr 2003 1 3,90 113 Degrès CD Rap Fr 2005 1 4,99 113 Un jour de paix CD Rap Fr 2006 1 2,99 113 Illegal Radio CD Rap Fr 2006 1 3,49 113 Universel CD Rap Fr 2010 1 5,99 1995 La suite CD Rap Fr 1995 1 9,40 Aaliyah One In A Million CD Hip Hop 1996 1 9 Aaliyah I refuse & more than a CD single RNB 2001 1 8 woman Aaliyah feat Timbaland We need a resolution CD Single -

L'expression Musicale De Musulmans Européens. Création De Sonorités Et

Revue européenne des migrations internationales vol. 25 - n°2 | 2009 Créations en migrations L’expression musicale de musulmans européens. Création de sonorités et normativité religieuse The Musical Expression of European Muslims. Creation of Tones in the Event of the Religious Norms La expresión musical de musulmanes europeos. Creación de sonoridades a la luz de las normas religiosas Farid El Asri Édition électronique URL : http://journals.openedition.org/remi/4946 DOI : 10.4000/remi.4946 ISSN : 1777-5418 Éditeur Université de Poitiers Édition imprimée Date de publication : 1 octobre 2009 Pagination : 35-50 ISBN : 978-2-911627-52-1 ISSN : 0765-0752 Référence électronique Farid El Asri, « L’expression musicale de musulmans européens. Création de sonorités et normativité religieuse », Revue européenne des migrations internationales [En ligne], vol. 25 - n°2 | 2009, mis en ligne le 01 octobre 2012, consulté le 17 mars 2021. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/remi/4946 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/remi.4946 © Université de Poitiers Revue Européenne des Migrations Internationales, 2009 (25) 2 pp. 35-50 35 L’expression musicale de musulmans européens Création de sonorités et normativité religieuse Farid EL ASRI* La présence musulmane en Europe est, pour une grande partie, originellement issue de l’immigration (Göle, 2005 ; Modood, Triandafyllidou, Zapata-Barrero, 2006 ; Nielsen, 1984 ; Nielsen, 1995 ; Parsons et Smeeding, 2006). Cette présence est également alimentée par des conversions à l’islam1 (Alliévi, 1998 ; Alliévi, 1999 ; Alliévi and Robert Schuman Centre, 2000 ; Minet, 2007 ; Rocher et Cherqaoui, 1986). Ses origines ne sont certainement pas monolithiques. Elle est originaire de nombreuses aires culturelles musul- manes. -

Rap and Islam in France: Arabic Religious Language Contact with Vernacular French Benjamin Hebblethwaite [email protected]

Rap and Islam in France: Arabic Religious Language Contact with Vernacular French Benjamin Hebblethwaite [email protected] 1. Context 2. Data & methods 3. Results 4. Analysis Kamelancien My research orientation: The intersection of Language, Religion and Music Linguistics French-Arabic • Interdisciplinary (language contact • Multilingual & sociolinguistics) • Multicultural • Multi-sensorial Ethnomusicology • Contemporary (rap lyrics) Religion This is a dynamic approach that links (Islam) language, culture and religion. These are core aspects of our humanity. Much of my work focuses on Haitian Vodou music. --La fin du monde by N.A.P. (1998) and Mauvais Oeil by Lunatic (2000) are considered breakthrough albums for lyrics that draw from the Arabic-Islamic lexical field. Since (2001) many artists have drawn from the Islamic lexical field in their raps. Kaotik, Paris, 2011, photo by Ben H. --One of the main causes for borrowing: the internationalization of the language setting in urban areas due to immigration (Calvet 1995:38). This project began with questions about the Arabic Islamic words and expressions used on recordings by French rappers from cities like Paris, Marseille, Le Havre, Lille, Strasbourg, and others. At first I was surprised by these borrowings and I wanted to find out how extensive this lexicon --North Africans are the main sources of Arabic inwas urban in rap France. and how well-known --Sub-Saharan Africans are also involved in disseminatingit is outside the of religiousrap. lexical field that is my focus. The Polemical Republic 2 recent polemics have attacked rap music • Cardet (2013) accuses rap of being a black and Arab hedonism that substitutes for political radicalism. -

Quarante Ans De Rap En France

Quarante ans de rap français : identités en crescendo Karim Hammou, Cresppa-CSU, 20201 « La pensée de Négritude, aux écrits d'Aimé Césaire / La langue de Kateb Yacine dépassant celle de Molière / Installant dans les chaumières des mots révolutionnaires / Enrichissant une langue chère à nombreux damnés d'la terre / L'avancée d'Olympe de Gouges, dans une lutte sans récompense / Tous ces êtres dont la réplique remplaça un long silence / Tous ces esprits dont la fronde a embelli l'existence / Leur renommée planétaire aura servi à la France2 » Le hip-hop, musique d’initiés tributaire des circulations culturelles de l’Atlantique noir Trois dates principales marquent l’ancrage du rap en France : 1979, 1982 et 1984. Distribué fin 1979 en France par la maison de disque Vogue, le 45 tours Rappers’ Delight du groupe Sugarhill Gang devient un tube de discothèque vendu à près de 600 000 exemplaires. Puis, dès 1982, une poignée de Français résidant à New York dont le journaliste et producteur de disques Bernard Zekri initie la première tournée hip hop en France, le New York City Rap Tour et invite le Rocksteady Crew, Grandmaster DST et Afrika Bambaataa pour une série de performances à Paris, Londres, mais aussi Lyon, Strasbourg et Mulhouse. Enfin, en 1984, le musicien, DJ et animateur radio Sidney lance l’émission hebdomadaire « H.I.P. H.O.P. » sur la première chaîne de télévision du pays. Pendant un an, il fait découvrir les danses hip hop et les musiques qui les accompagnent à un public plus large encore, et massivement composé d’enfants et d’adolescents. -

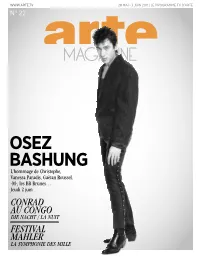

Osez Bashung

WWW.Arte.tv 28 MAI › 3 JUIN 2011 | LE PROGRAMME TV D’ARTE N° 22 OSEZ BASHUNG L’hommage de Christophe, Vanessa Paradis, Gaëtan Roussel, -M-, les BB Brunes… Jeudi 2 juin CONRAD AU CONGO DIE NacHT / LA NUIT FESTIVAL MAHLER LA SYMPHONIE DES MILLE ARTE LIVE WEB ARTE LIVE WEB PARTENAIRE DU FESTIVAL DE FÈS MUSIQUES SaCRÉES DU MONDE DU 3 AU 12 JUIN 2011 Ben Harper, Youssou Ndour, Abd Al Malik, Maria Bethânia... Retrouvez les concerts sur arteliveweb.com LES GRANDS RENDEZ-VOUS SAMEDI 28 MAI › VENDREDI 3 JUIN 2011 “Ainsi pénétrions- nous plus avant chaque jour au cœur des ténèbres.” Joseph Conrad dans Die Nacht / La Nuit, mardi 31 mai à 0.50 Lire pages 6-7 et 19 SOULOY / GAMMA BASHUNG Une évocation inspirée du chanteur de “La nuit je mens”, à travers les voix de l’album hommage Tels - Alain Bashung : Christophe, Vanessa Paradis, -M-, Gaëtan Roussel, les BB Brunes... Jeudi 2 juin à 22.20 Lire pages 4-5 et 23 LA SYMPHONIE DES MILLE DIRIGÉE PAR RICCARDO CHAILLY Pour le concert de clôture du Festival Mahler de Leipzig, Riccardo Chailly ILS SE MARIÈRENT dirige la Symphonie n° 8 du composi- PATHÉ teur disparu il y a tout juste cent ans. ET EURENT BEAUCOUP Dimanche 29 mai à 18.15 Lire page 12 D’ENFANTS La crise de la quarantaine perturbe le quotidien de Vin- cent et Gabrielle, tout comme celui de leurs amis. Une comédie d’Yvan Attal drôle et touchante qui vous cueille sans prévenir. Avec Charlotte Gainsbourg, lumineuse. Jeudi 2 juin à 20.40 Lire page 22 N° 22 – Semaine du 28 mai au 3 juin 2011 – ARTE Magazine 3 EN COUVErtURE ARÈME C UDOVIC L BASHUNG PAR LES BB BRUNES C’est l’une des plus belles promesses de la scène rock française. -

Literatura Y Otras Artes: Hip Hop, Eminem and His Multiple Identities »

TRABAJO DE FIN DE GRADO « Literatura y otras artes: Hip Hop, Eminem and his multiple identities » Autor: Juan Muñoz De Palacio Tutor: Rafael Vélez Núñez GRADO EN ESTUDIOS INGLESES Curso Académico 2014-2015 Fecha de presentación 9/09/2015 FACULTAD DE FILOSOFÍA Y LETRAS UNIVERSIDAD DE CÁDIZ INDEX INDEX ................................................................................................................................ 3 SUMMARIES AND KEY WORDS ........................................................................................... 4 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................. 5 1. HIP HOP ................................................................................................................... 8 1.1. THE 4 ELEMENTS ................................................................................................................ 8 1.2. HISTORICAL BACKGROUND ................................................................................................. 10 1.3. WORLDWIDE RAP ............................................................................................................. 21 2. EMINEM ................................................................................................................. 25 2.1. BIOGRAPHICAL KEY FEATURES ............................................................................................. 25 2.2 RACE AND GENDER CONFLICTS ........................................................................................... -

Top Singles (15/02/2019

Top Albums (06/09/2019 - 13/09/2019) Pos. SD Artiste Titre Éditeur Distributeur 1 NISKA MR SAL CAPITOL MUSIC FRANCE UNIVERSAL MUSIC FRANCE 2 1 JEAN-BAPTISTE GUEGAN PUISQUE C'EST ÉCRIT SMART SONY MUSIC ENTERTAINMENT 3 2 VITAA & SLIMANE VERSUS MERCURY MUSIC GROUP UNIVERSAL MUSIC FRANCE 4 3 NEKFEU LES ÉTOILES VAGABONDES : EXPANSION SEINE ZOO RECORDS UNIVERSAL MUSIC FRANCE 5 YANNICK NOAH BONHEUR INDIGO COLUMBIA SONY MUSIC ENTERTAINMENT 6 7 ANGÈLE BROL INITIAL ARTIST SERVICES UNIVERSAL MUSIC FRANCE 7 5 LORENZO SEX IN THE CITY INITIAL ARTIST SERVICES UNIVERSAL MUSIC FRANCE 8 8 NINHO DESTIN REC. 118 / MAL LUNE MUSIC WARNER MUSIC FRANCE 9 10 SOPRANO PHOENIX REC. 118 WARNER MUSIC FRANCE 10 11 PNL DEUX FRERES BELIEVE BELIEVE 11 POST MALONE HOLLYWOOD'S BLEEDING DEF JAM RECORDINGS FRANCE 12 13 JUL RIEN 100 RIEN BELIEVE BELIEVE 13 12 EVA QUEEN MCA UNIVERSAL MUSIC FRANCE 14 16 MAÎTRE GIMS CEINTURE NOIRE SONY MUSIC DISTRIBUES SONY MUSIC ENTERTAINMENT 15 4 LANA DEL REY NORMAN FUCKING ROCKWELL! POLYDOR UNIVERSAL MUSIC FRANCE 16 18 TROIS CAFES GOURMANDS UN AIR DE RIEN PLAY TWO WARNER MUSIC FRANCE 17 OXMO PUCCINO LA NUIT DU REVEIL BELIEVE BELIEVE 18 IGGY POP FREE CAROLINE FRANCE UNIVERSAL MUSIC FRANCE 19 6 RILÈS WELCOME TO THE JUNGLE CAPITOL MUSIC FRANCE UNIVERSAL MUSIC FRANCE 20 14 AYA NAKAMURA NAKAMURA REC. 118 WARNER MUSIC FRANCE 21 15 ELSA ESNOULT 4 JLA PRODUCTIONS WAGRAM 22 17 NAPS ON EST FAIT POUR CA BELIEVE BELIEVE 23 19 LADY GAGA A STAR IS BORN SOUNDTRACK POLYDOR UNIVERSAL MUSIC FRANCE 24 20 ED SHEERAN NO.6 COLLABORATIONS PROJECT WEA WARNER MUSIC FRANCE 25 22 M. -

Journal N°48 Pages 1&2

3 1 0 2 AL HANANEWS 8 Juin 4 Les news du collège-lycée N ° Page 1 page mensuelle qui est la vôtre ( ات ا ) رج ال ا وا ر ا+* ا(وـ' إادي ، و" ار! أ وز ا(4.ذ 1 اوام 1* "اءة ا ا.-* أن -=> إ' وا";، 1: أ6ع ا78 6 و6! إ5.ر أزء !* 5?* 6"*، -==ا <ء ا+ @ إ' H5* +ح !E.F 6 ھزAB C* . ل ' اJر!ط ا=OP 6 اMN وأ?=> و7Lوره ا* . و<ب U@ ا78 =ا ; T=ص "اR* أ5ى و=1ت * M" *L أ1=اش، واUرة وا"* ااHY* وا"* اF=ار* وXھ. UHا 78P MU ا+* ا(و' اادي 1ن 2 6@ اU اا . Quel est pour vous le mot de l'année 2013? l Hanane II: Vous êtes appelés à contribuer à cette La troupe DanceFever présente son Le Festival du Mot de la Charité-sur-Loire nouveau spectacle: "Show time", le vendredi 07 juin et le samedi 08 juin propose comme chaque année d'élire le mot de 2013 à 21h au Robinson club d'Agadir l'année parmi dix propositions. "Un mot qui illustre le mieux l'année en cours. Pour l'année 2013, le jury de lexicologues, sociologues et journalistes a considéré que TRANSPARENCE était le mot de l’année tandis que les 75.000 votants de cette année ont préféré MENSONGE(S). Pour rappel, en 2005 le mot de l'année était "précarité", en 2006 "respect", en 2007 bravitude*, en 2008 "bling-bling", en 2009 "parachute doré", en 2010 "dette", en 2011 Rédacteurs du collège et du lycée A "Dégage!", en 2012 "changement" (choix du public) et "Twitter" (choix du jury). -

TRIBUNAL DE GRANDE INSTANCE DE PARIS JUGEMENT Rendu Le 25 Avril 2013 3Ème Chambre 4Ème Section N° RG : 12/02167 DEMANDEURS Ma

TRIBUNAL DE GRANDE INSTANCE DE PARIS JUGEMENT rendu le 25 Avril 2013 3ème chambre 4ème section N° RG : 12/02167 DEMANDEURS Madame Sophie S Monsieur Rodolphe G Monsieur Florent G représentés par Me Pierre LAUTIER, avocat au barreau de PARIS, vestiaire #B0925 DÉFENDEURS Monsieur A dit "ONE SHOT" défaillant S.A.R.L. QUATRE ETOILES, [...] 75020 PARIS défaillant S.A.R.L. BECAUSE EDITIONS [...] 75009 PARIS représentée par Me Jean LATRILLE, avocat au barreau de PARIS, vestiaire #B0359 SONY ATV MUSIC PUBLISHING [...] 75017 PARIS représentée par Me Eric LAUVAUX de la SELARL NOMOS, avocat au barreau de PARIS, vestiaire #L0237 UNIVERSAL MUSIC FRANCE [...] 75005 PARIS représentée par Me Nicolas BOESPFLUG, avocat au barreau de PARIS, vestiaire #E0329 Monsieur Elie Y dit BOOBA S.A.R.L. TALLAC PUBLISHING [...] 92360 MEUDON LA FORET S.A.R.L. TALLAC RECORDS [...] 92360 MEUDON LA FORET représentées par Me Simon TAHAR de la SCP SCP TAHAR & ROSNAY - VEIL, avocat au barreau de PARIS, avocat plaidant, vestiaire #P0394 COMPOSITION DU TRIBUNAL Marie-Claude H, Vice-Présidente François T, Vice-Président Laure COMTE, Juge assistés de Katia CARDINALE, Greffier DEBATS A l'audience du 20 Mars 2013 tenue publiquement JUGEMENT Rendu par mise à disposition au greffe Réputé contradictoire en premier ressort FAITS PROCÉDURE PRÉTENTIONS ET MOYENS DES PARTIES ; José GARCIA M, dit G, était un magicien et un humoriste ; il est décédé le 18 avril 2000. II a laissé à sa succession : - Sophie GARCIA M née S, sa veuve, - Rodolphe GARCIA M, son fils, - Florent GARCIA M, son fils. Le 08 octobre 2001, Sophie GARCIA M, Rodolphe GARCIA M et Florent GARCIA M ont déposé la marque "GARCIMORE" pour des produits et services en classes 09,16, 28, 35, 38 et 41 enregistrée sous le n° 013 124 629 et renouvelée depuis. -

Dans Le Rap Français : Choix Ou Contrainte?»

«Ici trop confondent le rap, la rue et pôle emploi » clame Vin7, rappeur du TSR crew, au début de la chanson « Coup d'éclat » (Hugo TSR, Fenêtre sur rue , Chambre froide, 2012): ce genre d'affirmation, si elle a un tout autre sens dans le couplet du MC, est toutefois révélatrice des multiples « assignations minoritaires » (Hammou, 2012) que les dominants font peser sur les rappeurs : l'amalgame est rapidement fait entre un genre musical, où priment les mots, un lieu symbolique associé à une classe sociale -imaginée, et une situation de précarité qui les relieraient. Le rappeur et son écriture n'auraient d'intérêt, non pas en tant que tels, mais par ce qu'ils signifient d'autre : symptôme d'un « malaise des banlieues », forme d'expression privilégiée de la jeunesse racisée des quartiers populaires, le rap n'est que très peu envisagé d'un point de vue esthétique interne -tort partagé par les journalistes comme, jusqu'à peu, par les chercheur/ses en sciences sociales. Or, face à ce porte-parolat contraint, comment écrit-on le rap, du rap ? Les rappeurs peuvent refuser l'assignation minoritaire, lui opposer une proposition de « mandat esthétique généralisé » (Hammou, 2012) où ils revendiquent de l'artiste la part d'universel ; ou bien l'accepter, se l'approprier. Nous nous intéresserons ici particulièrement à la dernière option : parviennent-ils, en s'appropriant ces injonctions, à créer une poétique spécifique, qu'on pourrait appeler « populaire » ? « Le peuple peut-il s'écrire ? » Réflexivité <=> « rap conscient ». Pourquoi les contemporains qui ont fait de belles œuvres ne devraient être étudiés que dans 200 ans? Alors qu’on pourrait en parler aujourd’hui, leur poser des questions ? (Dooz Kawa) "Ecrire le « peuple » dans le rap français : choix ou contrainte?» Intro: Pourquoi la question du choix et de la contrainte : quand une séance sur rap avec intitulé « le peuple peut-il s'écrire ? », on associe vite le rap à une forme d'écriture populaire, des gens qui écriraient le peuple en venant du « peuple » (sens de la phrase de Vin7). -

Banlieue Violence in French Rap

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 2007-03-22 Je vis, donc je vois, donc je dis: Banlieue Violence in French Rap Schyler B. Chennault Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the French and Francophone Language and Literature Commons, and the Italian Language and Literature Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Chennault, Schyler B., "Je vis, donc je vois, donc je dis: Banlieue Violence in French Rap" (2007). Theses and Dissertations. 834. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/834 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. "JE VIS, DONC JE VOIS, DONC JE DIS." BANLIEUE VIOLENCE IN FRENCH RAP by Schyler Chennault A thesis submitted to the faculty of Brigham Young University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MA in French Studies Department of French and Italian Brigham Young University April 2007 ABSTRACT "JE VIS, DONC JE VOIS, DONC JE DIS." BANLIEUE VIOLENCE IN FRENCH RAP Schyler Chennault Department of French and Italian Master's Since its creation over two decades ago, French rap music has evolved to become both wildly popular and highly controversial. It has been the subject of legal debate because of its violent content, and accused of encouraging violent behavior. This thesis explores the French M.C.'s role as representative and reporter of the France's suburbs, la Banlieue, and contains analyses of French rap lyrics to determine the rappers' perception of Banlieue violence. -

La French Touch Du Hip-Hop À Mawazine Booba, Le Plus Fascinant Des Rappeurs Français Sera En Concert À L’OLM Le Mardi 16 Mai

COMMUNIQUE DE PRESSE e 16 édition du Festival Mawazine Rythmes du Monde La French Touch du hip-hop à Mawazine Booba, le plus fascinant des rappeurs français sera en concert à l’OLM le mardi 16 mai. Rabat, jeudi 16 mars 2017 : La 16e édition célèbre une des grandes figures de la scène urbaine française : Booba, qui se produira à l’OLM le mardi 16 mai. Huit disques d'or et cinq disques de platine dont trois double disque de platine : Booba est de loin le premier rappeur français, toutes ventes confondues. De son vrai nom Elie Yaffa, ce Franco-Sénégalais né en 1976, devient Booba quand il commence à rapper à Boulogne dans les Hauts-de-Seine. Après des débuts avec le collectif Beat 2 Boul, qui réunit les Sages Poètes de la Rue, et l'écurie Time Bomb, qui rassemble Pit Baccardi et Oxmo Puccino, Booba fonde avec le rappeur Ali le duo Lunatic, qui agitera l’underground pendant de nombreuses années. Le premier album du groupe, Mauvais oeil, sorti en 2000 sous le label indépendant 45 Scientific, créé pour l’occasion, est le premier à recevoir un Disque d'or attribué à un label de rap 100% indépendant. S’en suit une carrière solo pour Booba, qui sort son premier opus, Temps Mort, et s’impose avec le tube Destinée. À la clé : un nouveau Disque d'or et un succès grandissant pour l’artiste, qui poursuit sa carrière en réalisant la bande originale du film Taxi 3. Via son nouveau label, Tallac Records, Booba sort Panthéon en 2004 et décroche un double Disque d'or.