Lessons of the 2018 Osaka Earthquake 1. Background

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Logistics Facility to Be Developed in Hirakata, Osaka Prefecture --Total Floor Space 20,398.12 M2; Whole-Building Lease to OTT Logistics Co., Ltd

August 11, 2014 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact Information: ORIX Corporation Corporate Planning Department Tel: +81-3-3435-3121 Fax: +81-3-3435-3154 URL: http://www.orix.co.jp/grp/en/ Logistics Facility in the BCP-suitable Kansai Inland Area Logistics Facility to Be Developed in Hirakata, Osaka Prefecture --Total Floor Space 20,398.12 m2; Whole-Building Lease to OTT Logistics Co., Ltd-- TOKYO, Japan – August 11, 2014 - ORIX Corporation (TSE: 8591; NYSE: IX), a leading integrated financial services group, today announced that it has decided to develop a BTS*1 logistics facility in Hirakata, Osaka Prefecture. The development area for this project is in an industrial park located approximately 3 km from the Hirakata-higashi and Hirakata Gakken interchanges on the Second Keihan Highway, and approximately 1.5 km from Nagao Station on the JR Katamachi Line. The location is suitable for deliveries to the Osaka and Kyoto areas, being located approximately 3 km from National Route 1, a major highway connecting Kyoto and Osaka. Moreover, from the business continuity planning perspective, the Kansai inland area is highly sought-after and considered scarce land resources suitable for logistics facility development. The project includes a whole-building lease to OTT Logistics Co., Ltd. The five-story building (four stories in the warehouse section) will have a gross area of 20,398.12 m2 on a site of 10,629.36 m2. Construction will commence in September 2014, and is scheduled for completion in July 2015. The ORIX Group’s logistics investment business started in 2003, initially focused in the development of BTS facilities. -

Outstanding Award (1)Title: My Colorful Life in Sakai

Outstanding Award (1)Title: My colorful life in Sakai (2)Name: WANG JINGXIAN 1.Charms of Sakai City Sakai is situated in Osaka Prefecture, Japan. As one of Japan's largest port cities, Sakai was known for its Samurai swords and remains the manufacturing center for the country's highest-quality knives. For foreign students like me, I think Sakai is full of happiness. I used to live in Shinsaibashi. Ever since I settled to Sakai, I have found that not only has the quality of life enhanced, but the daily expenses have also decreased. Compared with the bustling hustle of Osaka city, after a hard-working day wandering on the silent street, you can feel peace and warmth. Without the cover of high buildings, I can see the same moon as my family see in China. Although sometimes I feel homesick, I still feel vitality from the people who work hard to live. After coming to Sakai City, I feel that I have a close relationship with the locals. Every Friday, the Japanese language classroom of the public hall can thrill me. Through the communication with volunteer teachers, I've learned the culture of Sakai city that makes my life here more fulfilling. Joy can be shared on. Seeing the smiles of the choir members next to the Japanese classroom, I can feel the city is full of happiness. 2.OPU promotions Osaka Prefecture University(OPU) is one of the largest public universities in Japan. In 2022, Osaka Prefecture University and Osaka City University will merge. The new university will become the Japanese largest public university which has the potential to be the best university in Japan. -

Osaka's High-Tech Clusters and Market Potentials

Osaka Prefectural Government Osaka’s High-tech Clusters and Market Potentials September 2016 Osaka Prefectural Government Osaka Prefectural GovernmentLocation of Osaka KANSAI Osaka locates at the Kyoto center of western Shiga Hyogo Japan. 35miles 20 miles Osaka Nara Osaka City Wakayama Osaka Prefectural Government GDP & Population BUSINESS FRIENDNESS GDP of Osaka: The Number Of Population of Osaka: 7.5% of Japan, equal to Norway Establishments 8.85 million U.S.A. 161,632 in Kansai China 82,294 Osaka City 59,379 Japan 21.4% Germa… 35,332 Brazil 22,488 54.9% Russia 20,175 23.7% Mexico 11,846 Others Indone… 8,767 Osaka Prefecture (except Osaka City) Turkey 7,889 Sweed… 5,439 Norway 4,610 Osaka 4,435 ASIA-PACIFIC CITIES AustriaArgent… 4,076 OF THE FUTURE BUSINESS FRIENDNESS of Osaka Osaka is ranked among the world’s top 10. Osaka Prefectural Government Special Zone The Kansai Innovation Comprehensive 6 important targets Global Strategic Special Zone create the innovation Pharmaceutical Drugs Medical Device Preemptive Medicine Advanced Medical Technology (regenerative medicine) Battery Smart Community 4 Osaka PrefecturalPotential Government of Osaka 【Energy】(1) New Energy Potential No.1 in Lithium-ion battery World-class companies in Osaka production value ・Panasonic Corporation ・Sumitomo Electric Industries Others 13% Kansai Japan 87% 227 billion yen 2011 Survey of Production(METI) 2011 Primary Product Production Statistics (Kansai Bureau of Economy,Trade and Industry Feature In Osaka, there are a lot of enterprises that have important key technologies and gain a high market share in new energy industrial fields, Rechargeable Battery, Hydrogen and Fuel Cell. -

Kyoto Hyogo Osaka Nara Wakayama Shiga

Introduction of KANSAI, JAPAN KYOTO OSAKA HYOGO WAKAYAMA NARA SHIGA INVEST KANSAI Introduction Profile of KANSAI, JAPAN Kansai area Fukui Kobe Tokyo Tottori Kansai Kyoto Shiga Hyogo Osaka Mie Osaka Kyoto Nara Tokushima Wakayama ©Osaka Convention & Tourism Bureau With a population exceeding 20 million and an economy of $800 billion, the Kansai region plays a leading role in western Japan. Osaka is center of the region, a vast metropolitan area second only to Tokyo in scale. Three metropolises, located close to one another 30 minutes by train from Osaka to Kyoto, and to Kobe. Domestic Comparison International Comparison Compare to Capital economic zone (Tokyo) Comparison of economic scale (Asia Pacific Region) Kansai Tokyo (as percentage of Japan) (as percentage of Japan) Australia Area (km2) 27,095 7.2% 13,370 3.5% Korea Population (1,000) 20,845 16.3% 35,704 28.0% Kansai Gross Product of 879 15.6% 1,823 32.3% region (GPR) (US$billion) Indonesia (Comparison of Manufacturing) Taiwan Kansai Tokyo (as percentage of Japan) (as percentage of Japan) Thailand Manufacturing Singapore output (US$billion) 568 15.9% 621 17.4% Hong Kong Employment in manufacturing (1,000) 1,196 16.1% 1,231 16.6% New Zealand Number of new factory setup (*) 181 14.8% 87 7.1% 0 500 1000 1500 (Unit: US$ billion) Number of manufacturers in Kansai is equivalent to Tokyo which is twice its economic size. Economy scale of Kansai is comparable to economies in Asia Pacific Region. Source: Institute of Geographical Survey, Ministry of Internal Affair “Population Projection” “World -

Cross-Regional Perinatal Healthcare Systems: Efforts in Greater Kansai Area, Japan

Conferences and Lectures Cross-Regional Perinatal Healthcare Systems: Efforts in Greater Kansai Area, Japan JMAJ 53(2): 86–90, 2010 1 Noriyuki SUEHARA* Fukui Kyoto Shiga Introduction Hyogo Aiming to create a society in which any woman can give birth without any sense of anxiety, Japan’s Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare Osaka Mie (MHLW) has been promoting the establishment Nara and systemization of general perinatal medical Tokushima centers nationwide since 1996. Wakayama In Osaka Prefecture, Neonatal Mutual Coop- erative System (NMCS) was established in 1977, and then Obstetric & Gynecologic Cooperative System (OGCS) in 1978. This illustrates that sys- 100km temization of perinatal healthcare is in progress in Osaka. Under OGCS, six hospitals (namely Osaka Medical Center and Research Institute for Maternal and Child Health, Osaka City General Hospital, Takatsuki General Hospital, Aizenbashi Hospital, Kansai Medical University Hirakata Hospital, and Yodogawa Christian Hospital) are designated as Base Hospitals, plus, nine other facilities are designated as Sub-base Hospitals. These hospitals play a large role in the Osaka’s regional perinatal healthcare system. In 1999, Osaka Council on Perinatal Health- Tokyo care Strategies was established, and in December of that year Osaka Medical Center and Research 500 km Institute for Maternal and Child Health was des- ignated as the general perinatal medical center for Osaka Prefecture. Subsequently, four addi- fectural Government formulated Guideline for tional hospitals (Takatsuki General Hospital, Improving the Perinatal Emergency Medical Aizenbashi Hospital, Kansai Medical University System, and 13 regional perinatal medical centers Hirakata Hospital, and Osaka University Hospi- were approved. Furthermore, Osaka Prefecture tal) were designated as general perinatal medical Guidelines for Prioritizing Perinatal Healthcare centers, serving as core facilities for perinatal Functions were drawn up in December 2008 based healthcare system in Osaka. -

Hirakata Logistics Center Completed in Osaka Prefecture

Hirakata Logistics Center Completed in Osaka Prefecture TOKYO, Japan – July 31, 2015 - ORIX Corporation (“ORIX”), a leading integrated financial services group, announced that the construction of its BTS1 logistics facility, "Hirakata Logistics Center (the “Facility”)," located in Hirakata, Osaka Prefecture, completed today. The Facility is located in an industrial park located approximately 3 km from the Hirakata-higashi and Hirakata Gakken interchanges on the Second Keihan Highway, and approximately 1.5 km from Nagao Station on the JR Katamachi Line. The location is suitable for deliveries to the Osaka and Kyoto areas, being located approximately 3 km from National Route 1, a major highway connecting Kyoto and Osaka. The inland area in Kansai, where the Facility resides, is also in high demand for BCP sites. The Facility is a five-story building (four stories in the warehouse section) with the total floor space of 20,398.12 square meters on a site of 10,629.36 square meters. The Facility has been leased to OTT Logistics Co., Ltd. simultaneously when the construction of the building has completed. The ORIX Group‘s logistics investment business started in 2003, initially focused in the development of BTS facilities. From around 2008, utilizing its accumulated expertise, ORIX began shifting the business’ primary focus to the development of multi-tenanted facilities2. To date, ORIX has developed around 1,150,000 m2 of logistics facilities. Going forward, ORIX will provide value added services that leverage its unique group network to differentiate itself, as it continues to operate logistics facility development projects that contribute to meeting market demand. -

Essentials for Living in Osaka (English)

~Guidebook for Foreign Residents~ Essentials for Living in Osaka (English) Osaka Foundation of International Exchange October 2018 Revised Edition Essentials for Living in Osaka Table of Contents Index by Category ⅠEmergency Measures ・・・1 1. Emergency Telephone Numbers 2. In Case of Emergency (Fire, Sudden Sickness and Crime) Fire; Sudden Illness & Injury etc.; Crime Victim, Phoning for Assistance; Body Parts 3. Precautions against Natural Disasters Typhoons, Earthquakes, Collecting Information on Natural Disasters; Evacuation Areas ⅡHealth and Medical Care ・・・8 1. Medical Care (Use of medical institutions) Medical Care in Japan; Medical Institutions; Hospital Admission; Hospitals with Foreign Language Speaking Staff; Injury or Sickness at Night or during Holidays 2. Medical Insurance (National Health Insurance, Nursing Care Insurance and others) Medical Insurance in Japan; National Health Insurance; Latter-Stage Elderly Healthcare Insurance System; Nursing Care Insurance (Kaigo Hoken) 3. Health Management Public Health Center (Hokenjo); Municipal Medical Health Center (Medical Care and Health) Ⅲ Daily Life and Housing ・・・16 1. Looking for Housing Applying for Prefectural Housing; Other Public Housing; Looking for Private Housing 2. Moving Out and Leaving Japan Procedures at Your Old Residence Before Moving; After Moving into a New Residence; When You Leave Japan 3. Water Service Application; Water Rates; Points of Concern in Winter 4. Electricity Electricity in Japan; Application for Electrical Service; Payment; Notice of the Amount of Electricity Used 5. Gas Types of Gas; Gas Leakage; Gas Usage Notice and Payment Receipt 6. Garbage Garbage Disposal; How to Dispose of Other Types of Garbage 7. Daily Life Manners for Living in Japan; Consumer Affairs 8. When You Face Problems in Life Ⅳ Residency Management System・Basic Resident Registration System for Foreign Nationals・Marriage・Divorce ・・・27 1. -

2009 Outbreak and School Closure, Osaka Prefecture, Japan

LETTERS Influenza (H1N1) 2009 virus was spreading widely to each school’s administrator. The pre- other schools and communities and fecture-wide school closure strategy 2009 Outbreak and that school closures would be neces- may have had an effect on not only the School Closure, sary (1,2). reduction of virus transmission and Osaka Prefecture, The governor of Osaka decided elimination of successive large out- to close all 270 high schools and 526 breaks but also greater public aware- Japan junior high schools in Osaka Prefec- ness about the need for preventive To the Editor: The Osaka Prefec- ture from Monday, May 18, to Sunday, measures. tural Government, the third largest lo- May 24, following the weekend days cal authority in Japan and comprising of May 16 and 17 observed at most Acknowledgments 43 cities (total population 8.8 million), schools. Students were ordered to stay We thank the public health centers in was informed of a novel influenza out- at home (3). Most nurseries, primary Osaka, Sakai, Higashiosaka, and Takatsuki break on May 16, 2009. A high school schools, colleges, and universities for data collection and the National Insti- submitted an urgent report that ≈100 in the 9 cities with influenza cases tute of Infectious Disease, Tokyo, for help- students had influenza symptoms; voluntarily followed the governor’s ful advice. an independent report indicated that decision. Antiviral drugs were pre- scribed by local physicians to almost a primary school child also showed Ryosuke Kawaguchi, all students with confirmed infection; similar symptoms. Masaya Miyazono, families were given these drugs as a The Infection Control Law in Ja- Tetsuro Noda, prophylactic measure. -

Guidebook for Foreigners Living in Neyagawa

Guidebook for Foreigners Living in Neyagawa 外国人のための生活ガイドブック 英語版 First and Foremost This guide, a Guide Book for Foreigners Living in Neyagawa, was created in cooperation with NIEFA- (NPO)Neyagawa International Exchange and Friendship Association and it is available in 6 languages; English, Chinese, Korean, Tagalog, Spanish, Portuguese to assist international residents with daily living. It is hoped that with this those who come from other countries can live comfortably here in Neyagawa. This book provides valuable information on vital public services and resources Please note that his book is current as of March 2012. The information and schedules are subject to change. March 2012 Neyagawa City TABLE OF CONTENTS ◆ PLEASE◆ When inquiring at many of the following places, you will find that many individuals cannot respond in English, and as such, whenever possible, please inquire along with someone who understands Japanese. 1 In Event of Emergency 1 Contacting Police ・・・・ 1 21 Fire・Ambulance ・・・・ 1 1 3 Gas Leak ・・・・ 2 1 4 Earthquake ・・・・ 3 In Eve5 Typhoon ・・・・ 4 nt6 Lost or Left Behind ・・・・ 4 2of Legal Procedures and Assistance Eme 1 Status of Residence ・・・・ 6 rge 2 Foreigner Registration ・・・・ 7 ncy 3 Getting Married(Marriage Registration) ・・・・ 9 4 Getting a Divorce(Divorce Registration) ・・・・10 5 Loss of Life(Death Registration) ・・・・10 6 Child Birth(Birth Registration) ・・・・10 7 Registration a Personal Seal ・・・・11 8 National Health Insurance ・・・・11 3 Accommodation and Housing 1 How to Find Housing ・・・・12 2 Signing a Contract ・・・・13 3 Rent -

By Municipality) (As of March 31, 2020)

The fiber optic broadband service coverage rate in Japan as of March 2020 (by municipality) (As of March 31, 2020) Municipal Coverage rate of fiber optic Prefecture Municipality broadband service code for households (%) 11011 Hokkaido Chuo Ward, Sapporo City 100.00 11029 Hokkaido Kita Ward, Sapporo City 100.00 11037 Hokkaido Higashi Ward, Sapporo City 100.00 11045 Hokkaido Shiraishi Ward, Sapporo City 100.00 11053 Hokkaido Toyohira Ward, Sapporo City 100.00 11061 Hokkaido Minami Ward, Sapporo City 99.94 11070 Hokkaido Nishi Ward, Sapporo City 100.00 11088 Hokkaido Atsubetsu Ward, Sapporo City 100.00 11096 Hokkaido Teine Ward, Sapporo City 100.00 11100 Hokkaido Kiyota Ward, Sapporo City 100.00 12025 Hokkaido Hakodate City 99.62 12033 Hokkaido Otaru City 100.00 12041 Hokkaido Asahikawa City 99.96 12050 Hokkaido Muroran City 100.00 12068 Hokkaido Kushiro City 99.31 12076 Hokkaido Obihiro City 99.47 12084 Hokkaido Kitami City 98.84 12092 Hokkaido Yubari City 90.24 12106 Hokkaido Iwamizawa City 93.24 12114 Hokkaido Abashiri City 97.29 12122 Hokkaido Rumoi City 97.57 12131 Hokkaido Tomakomai City 100.00 12149 Hokkaido Wakkanai City 99.99 12157 Hokkaido Bibai City 97.86 12165 Hokkaido Ashibetsu City 91.41 12173 Hokkaido Ebetsu City 100.00 12181 Hokkaido Akabira City 97.97 12190 Hokkaido Monbetsu City 94.60 12203 Hokkaido Shibetsu City 90.22 12211 Hokkaido Nayoro City 95.76 12220 Hokkaido Mikasa City 97.08 12238 Hokkaido Nemuro City 100.00 12246 Hokkaido Chitose City 99.32 12254 Hokkaido Takikawa City 100.00 12262 Hokkaido Sunagawa City 99.13 -

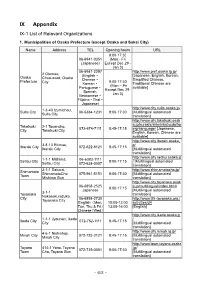

IX Appendix IX-1 List of Relevant Organizations

IX Appendix IX-1 List of Relevant Organizations 1. Municipalities of Osaka Prefecture (except Osaka and Sakai City) Name Address TEL Opening hours URL 9:00-17:30 06-6941-0351 (Mon - Fri (Japanese) Except Dec 29 - Jan 3) 06-6941-2297 http://www.pref.osaka.lg.jp/ 2 Otemae, (English・ [Japanese, English, Korean, Osaka Chuo-ward, Osaka Chinese・ Simplified Chinese, Prefecture 9:00-17:30 City Korean・ Traditional Chinese are (Mon – Fri Portuguese・ available] Except Dec 29- Spanish, Jan 3) Vietnamese・ Filipino・Thai・ Japanese) http://www.city.suita.osaka.jp/ 1-3-40 Izumichou, Suita City 06-6384-1231 9:00-17:30 [Multilingual automated Suita City translation] http://www.city.takatsuki.osak a.jp/kurashi/shiminkatsudo/for Takatsuki 2-1 Touencho, 072-674-7111 8:45-17:15 eignlanguage/ [Japanese, City Takatsuki City English, Korean, Chinese are available] http://www.city.ibaraki.osaka.j 3-8-13 Ekimae, p/ Ibaraki City 072-622-8121 8:45-17:15 Ibaraki City [Multilingual automated translation] http://www.city.settsu.osaka.jp 1-1-1 Mishima, 06-6383-1111 Settsu City 9:00-17:15 / [Multilingual automated Settsu City 072-638-0007 translation] 2-1-1 Sakurai, http://www.shimamotocho.jp/ Shimamoto ShimamotoCho 075-961-5151 9:00-17:30 [Multilingual automated Town Mishima Gun translation] http://www.city.toyonaka.osak 06-6858-2525 a.jp/multilingual/index.html/ 9:00-17:15 Japanese [Multilingual automated 3-1-1 Toyonaka translation] Nakasakurazuka, City 06-6858-2730 http://www.tifa-toyonaka.org./ Toyonaka City English(Mon, 10:00-12:00 activities/34 Tue, Thu & Fri) 13:00-16:00 -

European Respiratory Society Annual Congress 2013 Abstract Number: 693 Publication Number: P1393 Abstract Group: 12.3

European Respiratory Society Annual Congress 2013 Abstract Number: 693 Publication Number: P1393 Abstract Group: 12.3. Genetics and Genomics Keyword 1: Genetics Keyword 2: No keyword Keyword 3: No keyword Title: Association between ADAM33 polymorphisms and asthma control Dr. Guergana 8012 Petrova [email protected] MD 1,2, Dr. Hisako 8017 Matsumoto [email protected] MD 1, Dr. Yoshihiro 8018 Kanemitsu [email protected] MD 1, Dr. Kenji 8019 Izuhara [email protected] MD 3, Dr. Yuji 8020 Tohda [email protected] MD 4, Dr. Hideo 8026 Kita [email protected] MD 5, Dr. Takahiko 8028 Horiguchi [email protected] MD 6, Dr. Kazunobu 8030 Kuwabara [email protected] MD 6, Dr. Keisuke 8031 Tomii [email protected] MD 7, Dr. Kojiro 8032 Otsuka [email protected] MD 1,7, Dr. Masaki 8033 Fujimura [email protected] MD 8, Dr. Noriyuki 8034 Ohkura [email protected] MD 9, Dr. Katsuyuki 8035 Tomita [email protected] MD 4, Dr. Akihito 8036 Yokoyama [email protected] MD 9, Dr. Hiroshi 8037 Ohnishi [email protected] MD 9, Dr. Yasutaka 8038 Nakano [email protected] MD 10, Dr. Tetsuya 8039 Oguma [email protected] MD 10, Dr. Soichiro 8040 Hozaqa [email protected] MD 11, Dr. Tadao 8041 Nagasaki [email protected] MD 1, Dr. Isao 8042 Ito [email protected] MD 1, Dr.