Four Elements of Film

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Techniques of Cinematography: 2 (SUPROMIT MAITI)

Dept. of English, RNLKWC--SEM- IV—SEC 2—Techniques of Cinematography: 2 (SUPROMIT MAITI) The Department of English RAJA N.L. KHAN WOMEN’S COLLEGE (AUTONOMOUS) Midnapore, West Bengal Course material- 2 on Techniques of Cinematography (Some other techniques) A close-up from Mrinal Sen’s Bhuvan Shome (1969) For SEC (English Hons.) Semester- IV Paper- SEC 2 (Film Studies) Prepared by SUPROMIT MAITI Faculty, Department of English, Raja N.L. Khan Women’s College (Autonomous) Prepared by: Supromit Maiti. April, 2020. 1 Dept. of English, RNLKWC--SEM- IV—SEC 2—Techniques of Cinematography: 2 (SUPROMIT MAITI) Techniques of Cinematography (Film Studies- Unit II: Part 2) Dolly shot Dolly shot uses a camera dolly, which is a small cart with wheels attached to it. The camera and the operator can mount the dolly and access a smooth horizontal or vertical movement while filming a scene, minimizing any possibility of visual shaking. During the execution of dolly shots, the camera is either moved towards the subject while the film is rolling, or away from the subject while filming. This process is usually referred to as ‘dollying in’ or ‘dollying out’. Establishing shot An establishing shot from Death in Venice (1971) by Luchino Visconti Establishing shots are generally shots that are used to relate the characters or individuals in the narrative to the situation, while contextualizing his presence in the scene. It is generally the shot that begins a scene, which shoulders the responsibility of conveying to the audience crucial impressions about the scene. Generally a very long and wide angle shot, establishing shot clearly displays the surroundings where the actions in the Prepared by: Supromit Maiti. -

Film Terminology

Film Terminology Forms of Fiction English 12 Camera SHOTS camera shot is the amount of space that is seen in one shot or frame. Camera shots are used to demonstrate different aspects of a film's setting, characters and themes. As a result, camera shots are very important in shaping meaning in a film. Extreme long shot A framing in which the scale of the object shown is very small; a building, landscape, or crowd of people would fill the screen. Extreme long shot/Establishing shot This shot, usually involving a distant framing, that shows the spatial relations among the important figures, objects, and setting in a scene. Long Shot A framing in which the scale of the object shown is very small A standing human figure would appear nearly half the height of the screen. It is often used to show scenes of action or to establish setting - Sometimes called an establishing shot Medium long shot A framing at a distance that makes an object about four or five feet high appear to fill most of the screen vertically Medium Shot A framing in which the scale of the object shown is of moderate size A human figure seen from the waist up would fill most of the screen Over the shoulder This shot is framed from behind a person who is looking at the subject This shot helps to establish the position of each person and get the feel of looking at one person from the other’s point of view It is common to cut between these shots during conversation Medium close up A framing in which the scale of the object is fairly large a human figure seen from the chest up would fill most the screen Close-up Shot A framing in which the scale of the object shown is relatively large; most commonly a person’s head seen from the neck up, or an object of a comparable size that fills most of the screen. -

Cinematography

CINEMATOGRAPHY ESSENTIAL CONCEPTS • The filmmaker controls the cinematographic qualities of the shot – not only what is filmed but also how it is filmed • Cinematographic qualities involve three factors: 1. the photographic aspects of the shot 2. the framing of the shot 3. the duration of the shot In other words, cinematography is affected by choices in: 1. Photographic aspects of the shot 2. Framing 3. Duration of the shot 1. Photographic image • The study of the photographic image includes: A. Range of tonalities B. Speed of motion C. Perspective 1.A: Tonalities of the photographic image The range of tonalities include: I. Contrast – black & white; color It can be controlled with lighting, filters, film stock, laboratory processing, postproduction II. Exposure – how much light passes through the camera lens Image too dark, underexposed; or too bright, overexposed Exposure can be controlled with filters 1.A. Tonality - cont Tonality can be changed after filming: Tinting – dipping developed film in dye Dark areas remain black & gray; light areas pick up color Toning - dipping during developing of positive print Dark areas colored light area; white/faintly colored 1.A. Tonality - cont • Photochemically – based filmmaking can have the tonality fixed. Done by color timer or grader in the laboratory • Digital grading used today. A scanner converts film to digital files, creating a digital intermediate (DI). DI is adjusted with software and scanned back onto negative 1.B.: Speed of motion • Depends on the relation between the rate at which -

Camera Movement Terms

Camera Movement Terms Pan - Horizontal movement, left and right, you should use a tripod for a smooth effect. Why: To follow a subject or show the distance between two objects. Pan shots also work great for panoramic views such as a shot from a mountaintop to the valley below. Tilt - Vertical movement of the camera angle, i.e. pointing the camera up and down (as opposed to moving the whole camera up and down). Why: Like panning, to follow a subject or to show the top and bottom of a stationary object. With a tilt, you can also show how tall something is. Dolly -The camera physically follows the subject at a more or less constant distance. Why: To follow an object smoothly. Dolly Zoom - A technique in which the camera moves closer or further from the subject while simultaneously adjusting the zoom angle to keep the subject the same size in the frame. Why: This combination of lens movement and camera movement creates an effect like no other movement – It may create the illusion that the world is closing- in on the subject, or the opposite, the world and environment is expanding. Another possible ʻeffectʼ is as if the subject is floating towards the camera. Truck - Another term for tracking or dollying. Zoom - Technically this isn't a camera move, but a change in the lens focal length with gives the illusion of moving the camera closer or further away. Why: To bring objects at a distance closer to the lens, or to show size and perspective. Pedestal - Moving the camera position vertically (up and down) with respect to the subject (different than a tilt, the camera remains horizontal but moves vertically). -

" TERMINATOR " by James Cameron Registered

" T E R M I N A T O R " by James Cameron Registered WGAw Fourth Draft April 20, 1983 -------------------------------------------------------------------- TERMINATOR A1 TITLE SEQUENCE - SLITSCAN EFFECT A1 1 EXT. SCHOOLYARD - NIGHT 1 Silence. Gradually the sound of distant traffic becomes audible. A LOW ANGLE bounded on one side by a chain-link fence and on the other by the one-story public school build- ings. Spray-can hieroglyphics and distant streetlight sha- dows. This is a Los Angeles public school in a blue collar neighborhood. ANGLE BETWEEN SCHOOL BUILDINGS, where a trash dumpster looms in a LOW ANGLE, part of the clutter behind the gymnasium. A CAT enters FRAME. CAMERA DOLLIES FORWARD, prowling with him through the landscape of trash receptacles and shadows. CLOSE ON CAT, which freezes, alert, sensing something just beyond human perception. A sourceless wind rises, and with it a keening WHINE. Papers blow across the pavement. The cat YOWLS and hides under the dumpster. Windows rattle in their frames. The WHINE intensifies, accompanied now by a wash of frigid PURPLE LIGHT. A CONCUSSION like a thunderclap right over- head blows in all the windows facing the yard. C.U. - CAT, its eyes are wide as the glare dies. 1A/FX ANGLE - DUMPSTER 1A/FX ELECTRICAL DISCHARGES arc from the dumpster to a water faucet and climb a drain pipe like a Jacob's Ladder. CUT TO: 2 EXT. SCHOOLYARD - NIGHT 2 SLOW PAN as the sound of stray electrical CRACKLING subsides. FRAME comes to rest on the figure of a NAKED MAN kneeling, faced away, in the previously empty yard. -

Camera Shots/ Camera Angles/ Camera Movements Camera Shot

Camera Shots/ Camera Angles/ Camera Movements Camera Shot Camera Shot •This refers to the size of the subject in the frame. (How much of the person/subject we will see.) Extreme Long Shot Extreme Long Shot The Extreme Long Shot (ELS) is used to portray a vast area from an apparently long distance. An ELS is used to impress the viewer with the immense scope of the setting or scene. Often, the ELS makes it hard for the audience to connect with the characters emotionally. Long Shot Long Shot • The Long Shot (LS) shows the entire area where the action takes place. The whole subject is in frame. Medium Shot Medium Shot • The convention of the Medium Shot (MS), is (when framing a person) approximately half of their body is in shot, (from waist up). More subtle performances and detailed actions can be seen. The Medium Shot is a good framing for conversation scenes between characters, especially if hand movements are part of the performance. Medium Long Shot • The MLS can frame one or two people standing up, that is, their entire body. Close Up Close Up • The Close Up Shot (CU) shows a detail of the overall subject or action (the head or hands if it is a person). Close ups of characters are a good way of engaging the audience into the character emotionally. As we get closer to the character, we begin to lose the background information, therefore emphasizing the subject, rather than the background. Extreme Close Up Extreme Close Up • With the Extreme Close Up (ECU), a small detail of the subject is framed, such as a part of a human face, a hand, or foot. -

Saboteur (42) Rope (48) the Merry Widow Waltz

Shadow of a Doubt (43) Director of Photography-Joseph A. Valentine Wolfman (41) Saboteur (42) Rope (48) The Merry Widow Waltz after ring inscription discovered the first time w/i film proper we get merry widows waltzing couples the waltzers connect the two Charlie's "The image is never placed. If the scene of dancing is real, surely its world must be long past, viewed through a screen of nostalgia. If the scene is only a vision, whose vision is it? The film's opening raises the questions of who or what commands the camera and what motivates the presentation of this view. Shadow of a Doubt begins by declaring itself enigmatic, even before it announces that its projected world harbors a mystery within it. Charles's mystery is from the outset linked to the author's gesture of opening his film as he does." Rothman page 179 William Rothman's Hitchcock: The Murderous Gaze, Harvard 1984 "The dancing couples image specifically resonates with the picture of the lost idyll in The Lodger's flashback" Rothman page 179 Joseph Newton (Father): Well the bank gave me a raise last January. Young Charlie: Money! How can you talk about money when I'm talking about souls? The one right man to save us. “This tilt down to the money: this camera movement does not disclose the thoughts on which Cotton is dwelling. Why is this man rolling in money lying in bed in broad daylight in a seedy rooming house? Where has all the money come from and why is he so indifferent to it? In introducing him in this manner—rather, in withholding a proper introduction, in presenting him to us as unknown—the camera's autonomy is asserted, its enigma declared. -

Skvrnon" Hardmount Steadi Cam and Operator at Speeds up to 30 Mph With, As Skyman Is a New Vehicle Fo R They Say , Complete Aerial Steadicam Shots, Comfort and Safety

NEWS FOR OPERA Tons AND OWNERS Volume 3 number 2 A ri/1991 valleys, alleys, or arenas. Skyman carries both skvrnon" hardmount Steadi cam and operator at speeds up to 30 mph with, as Skyman is a new vehicle fo r they say , complete aerial Steadicam shots, comfort and safety. It invented and developed hy consis ts of an ultra Garrett Brown and Jerry light aerial cablecar Holway. (patent pending) with foot-operated brak ing and 360 degree rotation. COMPACT on Steadicam. Skyma n™ was designed to The Skyman project began in Magazine is prototyp e fabricated extend the capabilities of the Stead December as we prepa red for a demo from Arri IIC mag. Made out of icam system by providing a fast, of "C ablecam" (our remote camera Kevlar, the final design will be reliable, lo-tech "flying carpet" for gadget which rolls down a wire), for lighter, sleeker, and closer to shots over inaccess ible spaces such as Steven Spielberg's "Hook." Jerry camera body. rivers, canyons, busy intersections, Skyman, continued on page 2 The Moviecam Compact *This is a preliminary report . At the beginning ofMarch, I will he picking up a camera and will write a more extensive piece for the Stead icam Letter once I have had the opportunity to live with the Compact f or a while. - Ted Churchill The Moviec am Compact, Stead icam configuration: Technical spec s: • Body: Aluminum casting, integrated heater, regular and Super 35 forma ts, 12-32 FPS crys tal at one frame increments, 180 degree shutter, variable to 45 degrees. -

A Short List of Film Terms

A Short List of Film Terms Part of being a good film student is knowing the language of film. Here is a very brief introduction to some of the most common terms you will run across in my lectures and at ETC. It is by no means comprehensive; nonetheless, it should give you some basic terms to use when speaking and writing about your projects. For some of you, this list will be a review, but in everyone’s case, be sure to clarify any terms that you find confusing. A few of these terms come from literary analysis and from the theater, but most are specific to film. narrative - An adjective describing a film as being primarily a work of fiction, or a noun that loosely means a fictional story. documentary - Also an adjective or noun category used to describe a work of nonfiction. plot - refers to all aspects of the narrative that we see on screen. For example, in the film Jaws, Chief Brody’s talking to the town council on screen would be part of the plot. story - refers to all aspects of the narrative that we do not see on screen; these aspects may include events before, during, or even after the plot of the film. In Jaws, for instance, Chief Brody had been a police officer in the city prior to the film’s beginning; this information is part of the story but not part of the plot. diegesis - refers to the narrative that we see on screen. This term is much more specific to film, however, and refers to the world that the characters inhabit as much as the plot of the film. -

Film Studies 101: the 30 Camera Shots Every Film Fan Needs to Know

Film Studies 101: The 30 Camera Shots Every Film Fan Needs To Know empireonline.com/movies/features/film-studies-101-camera-shots-styles Ian Freer, Illustrations By Olly Gibbs 16 Dec 2013 09:00Last updated: 6 Mar 2017 20:00 The cinematographer's art often seems as much black magic as technique, taking a few actors milling around a set and turning it into something cinematic, evocative and occasionally iconic. Amidst all the voodoo and mystery, however, there is concrete science behind those money shots so we've identified thirty of the most important camera shots to help you distinguish your dolly zooms from your Dutch tilts. Aerial Shot An exterior shot filmed from — hey! — the air. Often used to establish a (usually exotic) location. All films in the '70s open with one — FACT. Example: The opening of The Sound Of Music (1965). Altogether now, “The hills are alive..." Stream The Sound Of Music (1965) now with Amazon Video Arc Shot 1/8 A shot in which the subject is circled by the camera. Beloved by Brian De Palma, Michael Bay. Example: The shot in De Palma's Carrie (1976) where Carrie White (Sissy Spacek) and Tommy Ross (William Katt) are dancing at the prom. The swirling camera move represents her giddy euphoria, see? Stream Carrie now with Amazon Video Bridging Shot A shot that denotes a shift in time or place, like a line moving across an animated map. That line has more air miles than Richard Branson. Example: The journey from the US to Nepal in Raiders Of The Lost Ark (1981). -

Film Terms Glossary Cinematic Terms Definition and Explanation Example (If Applicable) 180 Degree Rule a Screen Direction Rule T

Film Terms Glossary Cinematic Terms Definition and Explanation Example (if applicable) a screen direction rule that camera operators must follow - Camera placement an imaginary line on one side of the axis of action is made must adhere to the (e.g., between two principal actors in a scene), and the 180 degree rule 180 degree rule camera must not cross over that line - otherwise, there is a distressing visual discontinuity and disorientation; similar to the axis of action (an imaginary line that separates the camera from the action before it) that should not be crossed Example: at 24 fps, 4 refers to the standard frame rate or film speed - the number projected frames take 1/6 of frames or images that are projected or displayed per second to view second; in the silent era before a standard was set, many 24 frames per second films were projected at 16 or 18 frames per second, but that rate proved to be too slow when attempting to record optical film sound tracks; aka 24fps or 24p Examples: the first major 3D feature film was Bwana Devil (1953) [the first a film that has a three-dimensional, stereoscopic form or was Power of Love (1922)], House of Wax appearance, giving the life-like illusion of depth; often (1953), Cat Women of the Moon (1953), the achieved by viewers donning special red/blue (or green) or MGM musicalKiss Me Kate polarized lens glasses; when 3-D images are made (1953), Warner's Hondo (1953), House of 3-D interactive so that users feel involved with the scene, the Wax (1953), a version of Hitchcock's Dial M experience is -

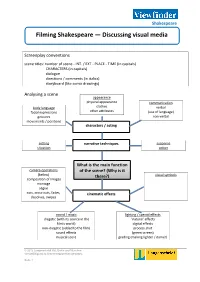

Filming Shakespeare — Discussing Visual Media

Shakespeare Filming Shakespeare — Discussing visual media Screenplay conventions scene titles: number of scene ‐ INT. / EXT ‐ PLACE ‐ TIME (in capitals) CHARACTERS (in capitals) dialogue directions / comments (in italics) storyboard (like comic drawings) Analysing a scene appearance physical appearance communication clothes verbal body language facial expressions other attributes (use of language) gestures non‐verbal movements / positions characters / acting setting narrative techniques suspense situation action What is the main function camera operations of the scene? (Why is it (below) there?) visual symbols composition of images montage segue cuts, cross‐cuts, fades, cinematic effects dissolves, swipes sound / music lighting / special effects diegetic (with its source in the 'natural' effects film's world) digital effects non‐diegetic (added to the film) process shot sound effects (green screen) musical score grading (making lighter / darker) © 2012 Langenscheidt KG, Berlin und München Vervielfältigung zu Unterrichtszwecken gestattet. Seite 1 Shakespeare Camera Operations high‐angle shot (from above) establishing shot to show the location at the start of a scene static shot (camera does not move) low‐angle shot (from below) long shot / wide shot (shows people or objects at a distance) to pan left/right (horizontal) to tilt up/down (vertical) eye‐level shot full shot (shows the whole body or object) crane shot (camera moves flexibly in all directions) over‐the‐shoulder shot medium shot (upper body or part of object) to focus on (to be in focus / reverse‐angle shot (showing the out of focus) other person in the dialogue) to zoom out (away from s.o.) close‐up (head and shoulders) tracking shot (on rails) extreme close‐up (detail of emotions) camera on a dolly (to dolly in / out) (to move in / pull out) overhead shot / bird's eye view to zoom in (on someone) © 2012 Langenscheidt KG, Berlin und München Vervielfältigung zu Unterrichtszwecken gestattet.