Classical Hollywood Cinema: Style

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Four Elements of Film

Four Elements of Film Mise-en-scène Mise-en-scène is everything that the audience can see in the frame. This includes the set ⎯ whether on location or in a studio, and some studio sets are so large that they can fool you into thinking you are seeing an on-location shot ⎯ props, lighting, the actors, costumes, make-up, blocking (where actors and extras stand), and movement, whether choreographed or not. All kinds of movement, from crossing a room to a sword-fight, can be choreographed, not just dance. Mise-en-scène demonstrates how film is the ultimate collaborative art, requiring contributions from professionals with a wide variety of skills. Cinematography Cinematography is the way in which a shot is framed, lit, shadowed, and colored. The way a camera moves, stands still, or pans (stands still while changing where it points), the angle from which it views the action, whether it elevates (usually a crane shot, when the camera is mounted on a crane, but sometimes a director will employ a helicopter shot instead), whether it follows a particular actor or object (a tracking shot, also called a dolly shot, because the camera is placed on a dolly, meaning a small, wheeled platform), zooms in, zooms out ⎯ these all affect the way the audience views the action, whether literally or metaphorically. Think of cinematography as being to a film what a narrator is to prose fiction. Sound Sound is probably the element of film that people most often underestimate. It includes dialogue, ambient sound, sound effects, and music. Consider how a “Boing!” sound in the soundtrack would change how we view a love scene or a scene in which an old lady falls down. -

Techniques of Cinematography: 2 (SUPROMIT MAITI)

Dept. of English, RNLKWC--SEM- IV—SEC 2—Techniques of Cinematography: 2 (SUPROMIT MAITI) The Department of English RAJA N.L. KHAN WOMEN’S COLLEGE (AUTONOMOUS) Midnapore, West Bengal Course material- 2 on Techniques of Cinematography (Some other techniques) A close-up from Mrinal Sen’s Bhuvan Shome (1969) For SEC (English Hons.) Semester- IV Paper- SEC 2 (Film Studies) Prepared by SUPROMIT MAITI Faculty, Department of English, Raja N.L. Khan Women’s College (Autonomous) Prepared by: Supromit Maiti. April, 2020. 1 Dept. of English, RNLKWC--SEM- IV—SEC 2—Techniques of Cinematography: 2 (SUPROMIT MAITI) Techniques of Cinematography (Film Studies- Unit II: Part 2) Dolly shot Dolly shot uses a camera dolly, which is a small cart with wheels attached to it. The camera and the operator can mount the dolly and access a smooth horizontal or vertical movement while filming a scene, minimizing any possibility of visual shaking. During the execution of dolly shots, the camera is either moved towards the subject while the film is rolling, or away from the subject while filming. This process is usually referred to as ‘dollying in’ or ‘dollying out’. Establishing shot An establishing shot from Death in Venice (1971) by Luchino Visconti Establishing shots are generally shots that are used to relate the characters or individuals in the narrative to the situation, while contextualizing his presence in the scene. It is generally the shot that begins a scene, which shoulders the responsibility of conveying to the audience crucial impressions about the scene. Generally a very long and wide angle shot, establishing shot clearly displays the surroundings where the actions in the Prepared by: Supromit Maiti. -

COM 320, History of the Moving Image–The Origins of Editing Styles And

COM 320, History of Film–The Origins of Editing Styles and Techniques I. The Beginnings of Classical/Hollywood Editing (“Invisible Editing”) 1. The invisible cut…Action is continuous and fluid across cuts 2. Intercutting (between 2+ different spaces; also called parallel editing or crosscutting) -e.g., lack of intercutting?: The Life of An American Fireman (1903) -e.g., D. W. Griffith’s Broken Blossoms (1919) (boxing match vs. girl/Chinese man encounter) 3. Analytical editing -Breaks a single space into separate framings, after establishing shot 4. Continguity editing…Movement from space to space -e.g., Rescued by Rover (1905) 5. Specific techniques 1. Cut on action 2, Match cut (vs. orientation cut?) 3. 180-degree system (violated in Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920)) 4. Point of view (POV) 5. Eyeline match (depending on Kuleshov Effect, actually) 6. Shot/reverse shot II. Soviet Montage Editing (“In-Your-Face Editing”) 1. Many shots 2. Rapid cutting—like Abel Gance 3. Thematic montage 4. Creative geography -Later example—Alfred Hitchcock’s The Birds 5. Kuleshov Effect -Established (??) by Lev Kuleshov in a series of experiments (poorly documented, however) -Nature of the “Kuleshov Effect”—Even without establishing shot, the viewer may infer spatial or temporal continuity from shots of separate elements; his supposed early “test” used essentially an eyeline match: -e.g., man + bowl of soup = hunger man + woman in coffin = sorrow man + little girl with teddy bear = love 6. Intercutting—expanded use from Griffith 7. Contradictory space -Shots of same event contradict one another (e.g., plate smashing in Potemkin) 8. Graphic contrasts -Distinct change in composition or action (e.g., Odessa step sequence in Potemkin) 9. -

The General Idea Behind Editing in Narrative Film Is the Coordination of One Shot with Another in Order to Create a Coherent, Artistically Pleasing, Meaningful Whole

Chapter 4: Editing Film 125: The Textbook © Lynne Lerych The general idea behind editing in narrative film is the coordination of one shot with another in order to create a coherent, artistically pleasing, meaningful whole. The system of editing employed in narrative film is called continuity editing – its purpose is to create and provide efficient, functional transitions. Sounds simple enough, right?1 Yeah, no. It’s not really that simple. These three desired qualities of narrative film editing – coherence, artistry, and meaning – are not easy to achieve, especially when you consider what the film editor begins with. The typical shooting phase of a typical two-hour narrative feature film lasts about eight weeks. During that time, the cinematography team may record anywhere from 20 or 30 hours of film on the relatively low end – up to the 240 hours of film that James Cameron and his cinematographer, Russell Carpenter, shot for Titanic – which eventually weighed in at 3 hours and 14 minutes by the time it reached theatres. Most filmmakers will shoot somewhere in between these extremes. No matter how you look at it, though, the editor knows from the outset that in all likelihood less than ten percent of the film shot will make its way into the final product. As if the sheer weight of the available footage weren’t enough, there is the reality that most scenes in feature films are shot out of sequence – in other words, they are typically shot in neither the chronological order of the story nor the temporal order of the film. -

TRANSCRIPT Editing, Graphics and B Roll, Oh

TRANSCRIPT Editing, Graphics and B Roll, Oh My! You’ve entered the deep dark tunnel of creating a new thing…you can’t see the light of day… Some of my colleagues can tell you that I am NOT pleasant to be around when I am in the creative video-making tunnel and I feel like none of the footage I have is working the way I want it to, and I can’t seem to fix even the tiniest thing, and I’m convinced all of my work is garbage and it’s never going to work out right and… WOW. Okay deep breaths. I think it’s time to step away from the expensive equipment and go have a piece of cake…I’ll be back… Editing, for me at least, is the hardest, but also most creatively fulfilling part of the video-making process. I have such a love/hate relationship with editing because its where I start to see all the things I messed up in the planning and filming process. But it’s ALSO where - when I let it - my creativity pulls me in directions that are BETTER than I planned. Most of my best videos were okay/mediocre in the planning and filming stages, but became something special during the editing process. So, how the heck do you do it? There are lots of ways to edit, many different styles, formats and techniques you can learn. But for me at least, it comes down to being playful and open to the creative process. This is the time to release your curious and playful inner child. -

MANUAL Set-Up and Operations Guide Glidecam Industries, Inc

GLIDECAM HD-SERIES 1000/2000/4000 MANUAL Set-up and Operations Guide Glidecam Industries, Inc. 23 Joseph Street, Kingston, MA 02364 Customer Service Line 1-781-585-7900 Manufactured in the U.S.A. COPYRIGHT 2013 GLIDECAM INDUSTRIES, INC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED PLEASE NOTE Since the Glidecam HD-2000 is essentially the same as the HD-1000 and the HD-4000, this manual only shows photographs of the Glidecam HD-2000 being setup and used. The Glidecam HD-1000 and the HD-4000 are just smaller and larger versions of the HD-2000. When there are important differences between the HD-2000 and the HD-1000 or HD-4000 you will see it noted with a ***. Also, the words HD-2000 will be used for the most part to include the HD-1000 and HD-4000 as well. 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION # PAGE # 1. Introduction 4 2. Glidecam HD-2000 Parts and Components 6 3. Assembling your Glidecam HD-2000 10 4. Attaching your camera to your Glidecam HD-Series 18 5. Balancing your Glidecam HD-2000 21 6. Handling your Glidecam HD-2000 26 7. Operating your Glidecam HD-2000 27 8. Improper Techniques 29 9. Shooting Tips 30 10. Other Camera Attachment Methods 31 11. Professional Usage 31 12. Maintenance 31 13. Warning 32 14. Warranty 32 15. Online Information 33 3 #1 INTRODUCTION Congratulations on your purchase of a Glidecam HD-1000 and/or Glidecam HD-2000 or Glidecam HD-4000. The amazingly advanced and totally re-engineered HD-Series from Glidecam Industries represents the top of the line in hand-held camera stabilization. -

Film Terminology

Film Terminology Forms of Fiction English 12 Camera SHOTS camera shot is the amount of space that is seen in one shot or frame. Camera shots are used to demonstrate different aspects of a film's setting, characters and themes. As a result, camera shots are very important in shaping meaning in a film. Extreme long shot A framing in which the scale of the object shown is very small; a building, landscape, or crowd of people would fill the screen. Extreme long shot/Establishing shot This shot, usually involving a distant framing, that shows the spatial relations among the important figures, objects, and setting in a scene. Long Shot A framing in which the scale of the object shown is very small A standing human figure would appear nearly half the height of the screen. It is often used to show scenes of action or to establish setting - Sometimes called an establishing shot Medium long shot A framing at a distance that makes an object about four or five feet high appear to fill most of the screen vertically Medium Shot A framing in which the scale of the object shown is of moderate size A human figure seen from the waist up would fill most of the screen Over the shoulder This shot is framed from behind a person who is looking at the subject This shot helps to establish the position of each person and get the feel of looking at one person from the other’s point of view It is common to cut between these shots during conversation Medium close up A framing in which the scale of the object is fairly large a human figure seen from the chest up would fill most the screen Close-up Shot A framing in which the scale of the object shown is relatively large; most commonly a person’s head seen from the neck up, or an object of a comparable size that fills most of the screen. -

Cinematography

CINEMATOGRAPHY ESSENTIAL CONCEPTS • The filmmaker controls the cinematographic qualities of the shot – not only what is filmed but also how it is filmed • Cinematographic qualities involve three factors: 1. the photographic aspects of the shot 2. the framing of the shot 3. the duration of the shot In other words, cinematography is affected by choices in: 1. Photographic aspects of the shot 2. Framing 3. Duration of the shot 1. Photographic image • The study of the photographic image includes: A. Range of tonalities B. Speed of motion C. Perspective 1.A: Tonalities of the photographic image The range of tonalities include: I. Contrast – black & white; color It can be controlled with lighting, filters, film stock, laboratory processing, postproduction II. Exposure – how much light passes through the camera lens Image too dark, underexposed; or too bright, overexposed Exposure can be controlled with filters 1.A. Tonality - cont Tonality can be changed after filming: Tinting – dipping developed film in dye Dark areas remain black & gray; light areas pick up color Toning - dipping during developing of positive print Dark areas colored light area; white/faintly colored 1.A. Tonality - cont • Photochemically – based filmmaking can have the tonality fixed. Done by color timer or grader in the laboratory • Digital grading used today. A scanner converts film to digital files, creating a digital intermediate (DI). DI is adjusted with software and scanned back onto negative 1.B.: Speed of motion • Depends on the relation between the rate at which -

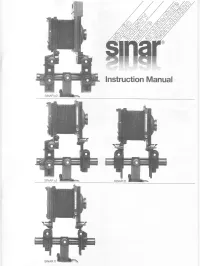

Manual Sinar P2 / C2 / F2 / F1-EN (PDF)

lnstructionManual The cameras Operatingcontrols of the SINAR iT p2andc2 1 Coarse-focusclamping lever 2 Finefocusing drive with depth of field scale 3 Micrometer drive for vertical (rise and fall) shift 4 Micrometer drive for lateral(cross) shift 5 Micrometerdrive for horizontal-axistilts 6 Micrometer drive for vertical-axisswings 7 lmageplane mark 8 Coarse-tilt (horizontal axis) clamping lever; movementused for verticalalignment of stan- dards with camerainclined up or down, alsofor coarse tilting to reservefull micrometertilt (5) rangefor sharpnessdistribution control. Fig.1 Contents The cameras 2 The planeof sharpnessand depthof field 11 - Controls 2 - Zerosettings Fufiher accessories 12 3 - - Mountingthe camera SINARCOLOR CONTROLfitters 12 4 - - The spirit levels Exposure meters 12 4 - - The base rail 4 AutomaticSINAR film holder - Changingcomponents 4 and shuttercoupling 12 - Film - The bellows 5 holders 13 - Camera backs s Final points 14 - Switchingformats p2 on the STNAR andc2 6 - Maintenance 14 - Switchingformats g on the SINARf2 andtl - Cleaning 14 - The convertible g camera - Adjusting the drives 14 - The bellowshood 9 - Cleaninglenses, filters and mirrors 14 - Viewingaids 9 - Warranty 14 - Transport l0 - Furtherinstruction manuals 14 The view camera movements 10 Remark: The camerac2 is no longerpart of the SINARsales programme, but can stiltrbe combined by the individualSINAR components. Operatingcontrols of the S|NARt2andtl 1 Coarse-focusclamping knob 2 Finefocussing drive with depthof fieldscale 3 Clampingwheel for verticalshift 4 Clampinglever for lateralshift 5 Clampinglever for swing (verticalaxis) 6 Clampinglever for tilt (horizontalaxis) 7 Angle-meteringscale for tilt and swingangles 8 lmageplane mark Zero setting points of the cameras CAMERAMODELS REAR(IMAGE) STANDARD FRONT(LENS) STANDARD NOTES SINARo2 With regularor special gxi|2 - 4x5 / White l White White dot for standardbearer 5x7 /13x18 Green i dots White lateralshift on With F/S back j or. -

Imovie Handout

Using iMovie iMovie is a video editing program that is available on Apple computers. It allows you to create and edit movies with titling and effects, so that you can export them to the Web. iMovie imports video from DV cameras. It can also import other video files, like mpeg or mov and formats from smartphones. The new version can import most video formats, but if you run into trouble, you can try a video converter like MPEG Streamclip to get the files in a format that iMovie will accept. You can import a digital clip as shown below. Most of your footage will be from a digital source. To import, you simply choose the Import button at the top of the screen. You can name the event (File, New Event), so you can organize your files. Once you have the event, you can simply drag from the finder to add the files or choose File, Import Media. Video Editing 1. Now you have several clips captured in your event library. You need to create a New Movie Project to work in. In the Projects tab, choose Create New. iMovie saves as you go, but it will later prompt you to save the project. 2. Now the screen is separated into three parts. There is the clip window and viewer at the top and the timeline at the bottom. You must move clips into the timeline to have them as part of your movie. 3. To select an entire clip, double-click. Put the playhead anywhere in the clip and hit the space bar to play. -

FILM & TELEVISION STUDIES Maste

FACULTY OF FINE ARTS SCHOOL OF FILM Secretariat Ikoniou 1, Stavroupoli, 56430 Tel.: +30 2310 990520 email: [email protected] ARISTOTLE UNIVERSITY OF THESSALONIKI FACULTY OF FINE ARTS SCHOOL OF FILM MASTER’S PROGRAM: FILM & TELEVISION STUDIES Master’s Thesis “Spatial and Temporal Continuity in One-Shot Films: Editing Goes Into Hiding” Georgios Dimoglou Prof. Eleftheria Thanouli Prof. Betty Kaklamanidou Prof. Stacey Abbott Thessaloniki, January 2021 School of Film, AUTh ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Firstly, I would like to express my deep gratitude to Prof. Eleftheria Thanouli and Prof. Betty Kaklamanidou for their valuable guidance in regard to my thesis and their unabated support since my undergraduate years. Their passion for research and knowledge of film and television continue to motivate me as a student and aspiring researcher. I also extend my gratitude to Prof. Stacey Abbott for the time she dedicated to the evaluation of this thesis as well as for being a most inspiring teacher. I would also like to thank my talented postgraduate colleagues for motivating me and especially Pavlina, Eva and Paul for their support and friendship. The COVID-19 era has been an extremely arduous one and a lot of my longtime friends came to my aid in numerous ways. I am deeply grateful to Anna, Elena, Sofianna and Efi for having my back when I needed them the most. Maya, Kostas, Vasilis and Vaggelis are another huge part of my years in Thessaloniki and I am most thankful for our shared treasured memories as well as the memories we will create in the future. I would also like to express my deep sense of gratitude to Alkisti for being a most supportive colleague and an irreplaceable friend. -

Modeling Crosscutting Services with UML Sequence Diagrams

Modeling Crosscutting Services with UML Sequence Diagrams Martin Deubler, Michael Meisinger, Sabine Rittmann Ingolf Krüger Technische Universität München Department of Computer Science Boltzmannstr. 3 University of California, San Diego 85748 München, Germany La Jolla, CA 92093-0114, USA {deubler, meisinge, [email protected] rittmann}@in.tum.de Abstract. Current software systems increasingly consist of distributed interact- ing components. The use of web services and similar middleware technologies strongly fosters such architectures. The complexity resulting from a high de- gree of interaction between distributed components – that we face with web service orchestration for example – poses severe problems. A promising ap- proach to handle this intricacy is service-oriented development; in particular with a domain-unspecific service notion based on interaction patterns. Here, a service is defined by the interplay of distributed system entities, which can be modeled using UML Sequence Diagrams. However, we often face functionality that affects or is spanned across the behavior of other services; a similar con- cept to aspects in Aspect-Oriented Programming. In the service-oriented world, such aspects form crosscutting services. In this paper we show how to model those; we introduce aspect-oriented modeling techniques for UML Sequence Diagrams and show their usefulness by means of a running example. 1 Introduction Today’s software systems get increasingly complex. Complexity is observed in all software application domains: In business information systems, technical and admin- istrative systems, as well as in embedded systems such as in avionics, automotive and telecommunications. Often, major sources of the complexity are interactions between system components. Current software architectures increasingly use distributed com- ponents as for instance seen when using web services [11] and service-oriented archi- tectures [7].