EDITING TECHNIQUES for FILM the Editing Process

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

COM 320, History of the Moving Image–The Origins of Editing Styles And

COM 320, History of Film–The Origins of Editing Styles and Techniques I. The Beginnings of Classical/Hollywood Editing (“Invisible Editing”) 1. The invisible cut…Action is continuous and fluid across cuts 2. Intercutting (between 2+ different spaces; also called parallel editing or crosscutting) -e.g., lack of intercutting?: The Life of An American Fireman (1903) -e.g., D. W. Griffith’s Broken Blossoms (1919) (boxing match vs. girl/Chinese man encounter) 3. Analytical editing -Breaks a single space into separate framings, after establishing shot 4. Continguity editing…Movement from space to space -e.g., Rescued by Rover (1905) 5. Specific techniques 1. Cut on action 2, Match cut (vs. orientation cut?) 3. 180-degree system (violated in Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920)) 4. Point of view (POV) 5. Eyeline match (depending on Kuleshov Effect, actually) 6. Shot/reverse shot II. Soviet Montage Editing (“In-Your-Face Editing”) 1. Many shots 2. Rapid cutting—like Abel Gance 3. Thematic montage 4. Creative geography -Later example—Alfred Hitchcock’s The Birds 5. Kuleshov Effect -Established (??) by Lev Kuleshov in a series of experiments (poorly documented, however) -Nature of the “Kuleshov Effect”—Even without establishing shot, the viewer may infer spatial or temporal continuity from shots of separate elements; his supposed early “test” used essentially an eyeline match: -e.g., man + bowl of soup = hunger man + woman in coffin = sorrow man + little girl with teddy bear = love 6. Intercutting—expanded use from Griffith 7. Contradictory space -Shots of same event contradict one another (e.g., plate smashing in Potemkin) 8. Graphic contrasts -Distinct change in composition or action (e.g., Odessa step sequence in Potemkin) 9. -

The General Idea Behind Editing in Narrative Film Is the Coordination of One Shot with Another in Order to Create a Coherent, Artistically Pleasing, Meaningful Whole

Chapter 4: Editing Film 125: The Textbook © Lynne Lerych The general idea behind editing in narrative film is the coordination of one shot with another in order to create a coherent, artistically pleasing, meaningful whole. The system of editing employed in narrative film is called continuity editing – its purpose is to create and provide efficient, functional transitions. Sounds simple enough, right?1 Yeah, no. It’s not really that simple. These three desired qualities of narrative film editing – coherence, artistry, and meaning – are not easy to achieve, especially when you consider what the film editor begins with. The typical shooting phase of a typical two-hour narrative feature film lasts about eight weeks. During that time, the cinematography team may record anywhere from 20 or 30 hours of film on the relatively low end – up to the 240 hours of film that James Cameron and his cinematographer, Russell Carpenter, shot for Titanic – which eventually weighed in at 3 hours and 14 minutes by the time it reached theatres. Most filmmakers will shoot somewhere in between these extremes. No matter how you look at it, though, the editor knows from the outset that in all likelihood less than ten percent of the film shot will make its way into the final product. As if the sheer weight of the available footage weren’t enough, there is the reality that most scenes in feature films are shot out of sequence – in other words, they are typically shot in neither the chronological order of the story nor the temporal order of the film. -

10 Tips on How to Master the Cinematic Tools And

10 TIPS ON HOW TO MASTER THE CINEMATIC TOOLS AND ENHANCE YOUR DANCE FILM - the cinematographer point of view Your skills at the service of the movement and the choreographer - understand the language of the Dance and be able to transmute it into filmic images. 1. The Subject - The Dance is the Star When you film, frame and light the Dance, the primary subject is the Dance and the related movement, not the dancers, not the scenography, not the music, just the Dance nothing else. The Dance is about movement not about positions: when you film the dance you are filming the movement not a sequence of positions and in order to completely comprehend this concept you must understand what movement is: like the French philosopher Gilles Deleuze said “w e always tend to confuse movement with traversed space…” 1. The movement is the act of traversing, when you film the Dance you film an act not an aestheticizing image of a subject. At the beginning it is difficult to understand how to film something that is abstract like the movement but with practice you will start to focus on what really matters and you will start to forget about the dancers. Movement is life and the more you can capture it the more the characters are alive therefore more real in a way that you can almost touch them, almost dance with them. The Dance is a movement with a rhythm and when you film it you have to become part of the whole rhythm, like when you add an instrument to a music composition, the vocabulary of cinema is just another layer on the whole art work. -

3. Master the Camera

mini filmmaking guides production 3. MASTER THE CAMERA To access our full set of Into Film DEVELOPMENT (3 guides) mini filmmaking guides visit intofilm.org PRE-PRODUCTION (4 guides) PRODUCTION (5 guides) 1. LIGHT A FILM SET 2. GET SET UP 3. MASTER THE CAMERA 4. RECORD SOUND 5. STAY SAFE AND OBSERVE SET ETIQUETTE POST-PRODUCTION (2 guides) EXHIBITION AND DISTRIBUTION (2 guides) PRODUCTION MASTER THE CAMERA Master the camera (camera shots, angles and movements) Top Tip Before you begin making your film, have a play with your camera: try to film something! A simple, silent (no dialogue) scene where somebody walks into the shot, does something and then leaves is perfect. Once you’ve shot your first film, watch it. What do you like/dislike about it? Save this first attempt. We’ll be asking you to return to it later. (If you have already done this and saved your films, you don’t need to do this again.) Professional filmmakers divide scenes into shots. They set up their camera and frame the first shot, film the action and then stop recording. This process is repeated for each new shot until the scene is completed. The clips are then put together in the edit to make one continuous scene. Whatever equipment you work with, if you use professional techniques, you can produce quality films that look cinematic. The table below gives a description of the main shots, angles and movements used by professional filmmakers. An explanation of the effects they create and the information they can give the audience is also included. -

How to Shoot Rich Cultural Training Videos on a Smartphone Table of Contents

How to Shoot Rich Cultural training Videos on a Smartphone Table of contents Introduction . 3 FOUR takeaways . 3 TOOLS YOU WILL NEED . 3 OUR PHILOSOPHY . 4 SET YOURSELF UP FOR SUcCESS . 4 PRE-PRODUCTION . 5 FINAL PRE-PRODUCTION PLANNING . 6 PRODUCTION . 6 FINAL PRODUCTION CHECKLIST . 7 POST-PRODUCTION . 8 The Video Tutorial . 10 Wisetail . 10 Contact. 11 2 INTRODUCTION four takeaways you can do this No. 1 The Secret to a great story The value of creating rich, engaging cultural stories No. 2 break down the to-dos for using video is often outweighed by the time, expertise planning the shoot, and outside resources needed to produce these videos. Especially in the L&D world, video creation is the one area where content creators and instructional designers No. 3 give you shooting tips and tricks, don’t feel comfortable just giving it a shot. No. 4 give you helpful pointers on In this guide, we will take you step-by-step through what to consider while editing the proven Wisetail video production process from a your video. filmmaking novice’s point of view. We’ll give you both the insight and techniques needed to tell your cultural stories using the tools (smartphone & laptop) already at your disposal. Tools you will need - Smartphone - Tripod (Helpful but not necessary) - Hard drive - Editing software - computer To watch the full video tutorial, go online to: wisetail.com/video 3 Our Philosophy Set yourself up for success The process and techniques of how to shoot video By asking yourself these questions, you’ll put on a smartphone are both very important. -

FILM & TELEVISION STUDIES Maste

FACULTY OF FINE ARTS SCHOOL OF FILM Secretariat Ikoniou 1, Stavroupoli, 56430 Tel.: +30 2310 990520 email: [email protected] ARISTOTLE UNIVERSITY OF THESSALONIKI FACULTY OF FINE ARTS SCHOOL OF FILM MASTER’S PROGRAM: FILM & TELEVISION STUDIES Master’s Thesis “Spatial and Temporal Continuity in One-Shot Films: Editing Goes Into Hiding” Georgios Dimoglou Prof. Eleftheria Thanouli Prof. Betty Kaklamanidou Prof. Stacey Abbott Thessaloniki, January 2021 School of Film, AUTh ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Firstly, I would like to express my deep gratitude to Prof. Eleftheria Thanouli and Prof. Betty Kaklamanidou for their valuable guidance in regard to my thesis and their unabated support since my undergraduate years. Their passion for research and knowledge of film and television continue to motivate me as a student and aspiring researcher. I also extend my gratitude to Prof. Stacey Abbott for the time she dedicated to the evaluation of this thesis as well as for being a most inspiring teacher. I would also like to thank my talented postgraduate colleagues for motivating me and especially Pavlina, Eva and Paul for their support and friendship. The COVID-19 era has been an extremely arduous one and a lot of my longtime friends came to my aid in numerous ways. I am deeply grateful to Anna, Elena, Sofianna and Efi for having my back when I needed them the most. Maya, Kostas, Vasilis and Vaggelis are another huge part of my years in Thessaloniki and I am most thankful for our shared treasured memories as well as the memories we will create in the future. I would also like to express my deep sense of gratitude to Alkisti for being a most supportive colleague and an irreplaceable friend. -

Film in Practice: the Making of "The Aventhrope," a Short Monster Movie

Trinity University Digital Commons @ Trinity Communication Honors Theses Communication Department 5-2017 Film in Practice: The akM ing of "The veA nthrope," A Short Monster Movie Robyn Wheelock Trinity University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.trinity.edu/comm_honors Recommended Citation Wheelock, Robyn, "Film in Practice: The akM ing of "The vA enthrope," A Short Monster Movie" (2017). Communication Honors Theses. 14. http://digitalcommons.trinity.edu/comm_honors/14 This Thesis open access is brought to you for free and open access by the Communication Department at Digital Commons @ Trinity. It has been accepted for inclusion in Communication Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Trinity. For more information, please contact [email protected]. (Film in Practice: The Making of “The Aventhrope,” A Short Monster Movie) (Robyn Wheelock) A DEPARTMENT HONORS THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF Communication AT TRINITY UNIVERSITY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR GRADUATION WITH DEPARTMENTAL HONORS 4/15/17 Dr. Aaron Delwiche and Dr. Jennifer Henderson Dr. Jennifer Henderson THESIS ADVISOR DEPARTMENT CHAIR Tim O’Sullivan, AVPAA Student Agreement I grant Trinity University (“Institution”), my academic department (“Department”), and the Texas Digital Library ("TDL") the non-exclusive rights to copy, display, perform, distribute and publish the content I submit to this repository (hereafter called "Work") and to make the Work available in any format in perpetuity as part of a TDL, Institution or Department repository communication or distribution effort. I understand that once the Work is submitted, a bibliographic citation to the Work can remain visible in perpetuity, even if the Work is updated or removed. -

BASIC FILM TERMINOLOGY Aerial Shot a Shot Taken from a Crane

BASIC FILM TERMINOLOGY Aerial Shot A shot taken from a crane, plane, or helicopter. Not necessarily a moving shot. Backlighting The main source of light is behind the subject, silhouetting it, and directed toward the camera. Bridging Shot A shot used to cover a jump in time or place or other discontinuity. Examples are falling calendar pages railroad wheels newspaper headlines seasonal changes Camera Angle The angle at which the camera is pointed at the subject: Low High Tilt Cut The splicing of 2 shots together. this cut is made by the film editor at the editing stage of a film. Between sequences the cut marks a rapid transition between one time and space and another, but depending on the nature of the cut it will have different meanings. Cross-cutting Literally, cutting between different sets of action that can be occuring simultaneously or at different times, (this term is used synonomously but somewhat incorrectly with parallel editing.) Cross-cutting is used to build suspense, or to show the relationship between the different sets of action. Jump cut Cut where there is no match between the 2 spliced shots. Within a sequence, or more particularly a scene, jump cuts give the effect of bad editing. The opposite of a match cut, the jump cut is an abrupt cut between 2 shots that calls attention to itself because it does not match the shots BASIC FILM TERMINOLOGY seamlessly. It marks a transition in time and space but is called a jump cut because it jars the sensibilities; it makes the spectator jump and wonder where the narrative has got to. -

Kubrick's Match Cut in 2001

Kubrick’s Match Cut in 2001: A Space Odyssey Stanley Kubrick’s renowned film, 2001: A Space Odyssey, is one of peculiar filmmaking and storytelling strategies. From the farfetched implications of the technological advancements of the future from a 1968 perspective to the use of odd motifs throughout the film, Kubrick’s film gives audiences something to think about throughout and after watching. One of the most significant scenes of the entire movie is the use of a match cut between the shot of a primate with a bone and an unknown spacecraft floating through outer space. A “match cut” can be defined as two shots edited consecutively which both possess a similar visual structure; the objects in a match cut are to be in the same place in each frame and have the same type of focus structure, as to not break the continuity of a plot and ultimately create a greater meaning of the story. In the case of 2001: A Space Odyssey, a bone is matched in the same vertically flying pattern as a spaceship in the second shot. In the former shot, the bone is propelled into the air after the primate who was holding it found new uses for it; as it is thrown in the air, it is put into a slow motion single shot, as to imply something for the audience to figure out. In the latter shot, the spaceship is in the same diagonal alignment as the bone in the previous shot and has the same type of shape. This match cut provided an array of arguments between filmmakers and historians alike regarding the implications of the shot’s meaning. -

Choices in the Editing Room

Choices in the Editing Room: How the Intentional Editing of Dialogue Scenes through Shot Choice can Enhance Story and Character Development within Motion Pictures Presented to the Faculty of Liberty University School of Communication & Creative Arts In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Master of Arts in Strategic Communication By Jonathan Pfenninger December 2014 Pfenninger ii Thesis Committee Carey Martin, Ph.D., Chair Date Stewart Schwartz, Ph.D. Date Van Flesher, MFA Date Pfenninger iii Copyright © 2014 Jonathan Ryan Pfenninger All Rights Reserved Pfenninger iv Dedication: To Momma and Daddy: The drive, passion, and love that you have instilled in me has allowed me to reach farther than I thought I would ever be able to. Pfenninger v Acknowledgements I would like to thank my parents, Arlen and Kelly Pfenninger, for their love and support throughout this journey. As you have watched me grow up there have been times when I have questioned whether I was going to make it through but you both have always stood strong and supported me. Your motivation has helped me know that I can chase my dreams and not settle for mediocrity. I love you. Andrew Travers, I never dreamed of a passion in filmmaking and storytelling before really getting to know you. Thank you for the inspiration and motivation. Dr. Martin, your example as a professor and filmmaker have inspired me over the last three years. I have gained an incredible amount of knowledge and confidence under your teaching and guidance. I cannot thank you enough for the time you have invested in me and this work. -

DOCUMENT RESUME CE 056 758 Central Florida Film Production Technology Training Program. Curriculum. Universal Studios Florida, O

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 326 663 CE 056 758 TITLE Central Florida Film Production Technology Training Program. Curriculum. INSTITUTION Universal Studios Florida, Orlando.; Valencia Community Coll., Orlando, Fla. SPONS AGENCY Office of Vocational and Adult Education (ED), Washington, DC. PUB DATE 90 CONTRACT V199A90113 NOTE 182p.; For a related final report, see CE 056 759. PUB TYPE Guides - Classroom Use - Teaching Guides (For Teacher) (052) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC08 Plus PoQtage. DESCRIPTORS Associate Degrees, Career Choice; *College Programs; Community Colleges; Cooperative Programs; Course Content; Curriculun; *Entry Workers; Film Industry; Film Production; *Film Production Specialists; Films; Institutional Cooperation; *Job Skills; *Occupational Information; On the Job Training; Photographic Equipment; *School TAisiness Relationship; Technical Education; Two Year Colleges IDENTIFIERS *Valencia Community College FL ABSTRACT The Central Florida Film Production Technology Training program provided training to prepare 134 persons for employment in the motion picture industry. Students were trained in stagecraft, sound, set construction, camera/editing, and post production. The project also developed a curriculum model that could be used for establishing an Associate in Science degree in film production technology, unique in the country. The project was conducted by a partnership of Universal Studios Florida and Valencia Community College. The course combined hands-on classroom instruction with participation in the production of a feature-length film. Curriculum development involved seminars with working professionals in the five subject areas, using the Developing a Curriculum (DACUM) process. This curriculum guide for the 15-week course outlines the course and provides information on film production careers. It is organized in three parts. Part 1 includes brief job summaries ofmany technical positions within the film industry. -

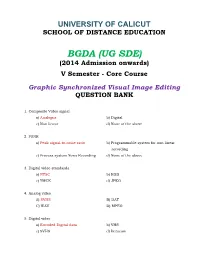

BGDA (UG SDE) (2014 Admission Onwards) V Semester - Core Course

UNIVERSITY OF CALICUT SCHOOL OF DISTANCE EDUCATION BGDA (UG SDE) (2014 Admission onwards) V Semester - Core Course Graphic Synchronized Visual Image Editing QUESTION BANK 1. Composite Video signal a) Analogue b) Digital c) Non linear d) None of the above 2. PSNR a) Peak signal-to-noise ratio b) Programmable system for non linear recording c) Process system News Recording d) None of the above 3. Digital video standards a) NTSC b) RGB c) YMCK d) JPEG 4. Analog video A) SVHS B) DAT C) WAV D) MPEG 5. Digital video a) Encoded Digital data b) VHS c) SVHS d) Betacam 6. Web Video a) Streaming b) Static c) Interface d) None of the above 7. Multimedia a) Text, Audio, Images b) Print media c) Cassette media d) None of the above 8. Digital era a) Information age b) LP Record age c) Video Cassette age d) None of the above 9. Final Cut Pro a) Video Editing b) Sound Mastering c) Image Editing d) None of the above 10. Action cutting a) Matching an action b) Removing an action c) Stopping an action d) None of the above 11. Rough cut a) Online Editing b) First process of editing c) Removing rough frames d) None of the above 12. Cross cutting a) Parallel editing b) Diagonally cutting c) Removing frames d) None of the above 13. VTR a) Video tape recording b) Video transferring and Removing c) Vector tape recording d) None of the above 14. Linear editing a) Ordered Sequence b) Interactive c) Dynamic d) None of the above 15.