Cyrus Dallin's the Scout

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Super Chief – El Capitan See Page 4 for Details

AUGUST- lyerlyer SEPTEMBER 2020 Ready for Boarding! Late 1960s Combined Super Chief – El Capitan see page 4 for details FLYER SALE ENDS 9-30-20 Find a Hobby Shop Near You! Visit walthers.com or call 1-800-487-2467 WELCOME CONTENTS Chill out with cool new products, great deals and WalthersProto Super Chief/El Capitan Pages 4-7 Rolling Along & everything you need for summer projects in this issue! Walthers Flyer First Products Pages 8-10 With two great trains in one, reserve your Late 1960s New from Walthers Pages 11-17 Going Strong! combined Super Chief/El Capitan today! Our next HO National Model Railroad Build-Off Pages 18 & 19 Railroads have a long-standing tradition of getting every last WalthersProto® name train features an authentic mix of mile out of their rolling stock and engines. While railfans of Santa Fe Hi-Level and conventional cars - including a New From Our Partners Pages 20 & 21 the 1960s were looking for the newest second-generation brand-new model, new F7s and more! Perfect for The Bargain Depot Pages 22 & 23 diesels and admiring ever-bigger, more specialized freight operation or collection, complete details start on page 4. Walthers 2021 Reference Book Page 24 cars, a lot of older equipment kept rolling right along. A feature of lumber traffic from the 1960s to early 2000s, HO Scale Pages 25-33, 36-51 Work-a-day locals and wayfreights were no less colorful, the next run of WalthersProto 56' Thrall All-Door Boxcars N Scale Pages 52-57 with a mix of earlier engines and equipment that had are loaded with detail! Check out these layout-ready HO recently been repainted and rebuilt. -

Volunteer Management Policies Stated Below

Girl Scouts of Northern California Volunteer Management Policy Board Approved: 7.23.2016 Girl Scouts of Northern California is governed by the policies of Girl Scouts of the USA (GSUSA) as stated in the Blue Book of Basic Documents 2015 edition and the Volunteer Management Policies stated below. The goal of the Girl Scouts of Northern California is to provide beneficial and safe program for girls. The Girl Scouts of Northern California Board of Directors has adopted the following as policy: Safety Volunteers and participants in the Girl Scout program should familiarize themselves with Volunteer Essentials and the Safety Activity Checkpoints, which outline the guidelines and checkpoints for maintaining a safe environment in which to conduct Girl Scout activities. All activities should be conducted following the Safety Activity Checkpoints and the guidelines listed in the Girl Scouts of Northern California Volunteer Essentials, or following state or federal laws, whichever is most stringent. Where no specific activity checkpoints or laws are stated, the guidelines of Girl Scouts of the USA and the policies and procedures of Girl Scouts of Northern California are recognized as the authority on the specific activity as an acceptable practice. Equal Opportunity/Affirmative Action Girl Scouts of Northern California seeks to offer volunteer opportunities to all adults, age 18 and up, regardless of race, color, creed, gender, religion, age, disability, sexual orientation, gender identity, national origin, ancestry, veteran status, citizenship, pregnancy, childbirth or other related medical condition, marital status or any other classification protected by federal, state or local laws or ordinances. Adult volunteers are selected on the basis of ability to perform the volunteer tasks, willingness and availability to participate in training for the position and acceptance of the principles and beliefs of Girl Scouting. -

Cornell Alumni News

Cornell Alumni News Volume 46, Number 22 May I 5, I 944 Price 20 Cents Ezra Cornell at Age of Twenty-one (See First Page Inside) Class Reunions Will 25e Different This Year! While the War lasts, Bonded Reunions will take the place of the usual class pilgrimages to Ithaca in June. But when the War is won, all Classes will come back to register again in Barton Hall for a mammoth Victory Homecoming and to celebrate Cornell's Seventy-fifth Anniversary. Help Your Class Celebrate Its Bonded Reunion The Plan is Simple—Instead of coming to your Class Reunion in Ithaca this June, use the money your trip would cost to purchase Series F War Savings Bonds in the name of "Cornell University, A Corporation, Ithaca, N. Y." Series F Bonds of $25 denomination cost $18.50 at any bank or post office. The Bonds you send will be credited to your Class in the 1943-44 Alumni Fund, which closes June 30. They will release cash to help Cornell through the difficult war year ahead. By your participation in Bonded Reunions: America's War Effort Is Speeded Cornell's War Effort Is Aided Transportation Loads Are Eased Campus Facilities ^re Saved Your Class Fund Is Increased Cornell's War-to-peace Conversion Your Money Does Double Duty Is Assured Send your Bonded Reunion War Bonds to Cornell Alumni Fund Council, 3 East Avenue, Ithaca, N. Y. Cornell Association of Class Secretaries Please mention the CORNELL ALUMNI NEWS Volume 46, Number 22 May 15, 1944 Price, 20 Cents CORNELL ALUMNI NEWS Subscription price $4 a year. -

Was the Thir

Tudor Place Manuscript Collection Paul Wayland Bartlett Papers MS-19 Introduction Paul Wayland Bartlett (1865-1925) was the third husband of Suzanne (Earle) Ogden-Jones Emmons Bartlett (1862-1954), the mother of Caroline (Ogden-Jones) Peter (1894-1965), wife of Armistead Peter 3rd (1896-1983) of Tudor Place. Suzanne (Earle) Ogden-Jones Emmons Bartlett retained all of her third husband’s papers and acted as his artistic executrix, organizing exhibitions of his work and casting some of his pieces to raise money for a memorial studio. Suzanne (Earle) Ogden-Jones Emmons Bartlett gave the bulk of her husband’s papers to the Library of Congress, but correspondence from Paul Wayland Bartlett’s father Truman Howe Bartlett (1835-1922), fellow artists, and business correspondence regarding various commissions, bills and receipts, news clippings, and printed material remained in her possession. This material spans the years 1887-1925, primarily between 1899 and 1920. Caroline (Ogden-Jones) Peter gave numerous pieces of her stepfather’s sculpture to museums around the country; the remaining papers and works of art were left at her death to her husband Armistead Peter 3rd. These papers were a part of the estate Armistead Peter placed under the auspices of the Carostead Foundation, Incorporated, in 1966; the name of the foundation was changed to Tudor Place Foundation, Incorporated, in 1987. Use and rights of the papers are controlled by the Foundation. The collection was processed by Anne Webb, the Foundation's archivist, and James Kaser, a project archivist hired through a National Historical Publications and Records Commission grant in 1992. -

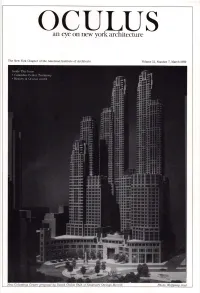

An Eye on New York Architecture

OCULUS an eye on new york architecture The New York Chapter of the American Institute of Architects Volume 51, Number 7, March 1989 ew Co lumbus Center proposal by David Childs FAIA of Skidmore Owings Merrill. 2 YC/AIA OC LUS OCULUS COMING CHAPTER EVENTS Volume 51, Number 7, March 1989 Oculus Tuesday, March 7. The Associates Tuesday, March 21 is Architects Lobby Acting Editor: Marian Page Committee is sponsoring a discussion on Day in Albany. The Chapter is providing Art Director: Abigail Sturges Typesetting: Steintype, Inc. Gordan Matta-Clark Trained as an bus service, which will leave the Urban Printer: The Nugent Organization architect, son of the surrealist Matta, Center at 7 am. To reserve a seat: Photographer: Stan Ri es Matta-Clark was at the center of the 838-9670. avant-garde at the end of the '60s and The New York Chapter of the American Institute of Architects into the '70s. Art Historian Robert Tuesday, March 28. The Chapter is 457 Madison Avenue Pincus-Witten will be moderator of the co-sponsoring with the Italian Marble New York , New York 10022 evening. 6 pm. The Urban Center. Center a seminar on "Stone for Building 212-838-9670 838-9670. Exteriors: Designing, Specifying and Executive Committee 1988-89 Installing." 5:30-7:30 pm. The Urban Martin D. Raab FAIA, President Tuesday, March 14. The Art and Center. 838-9670. Denis G. Kuhn AIA, First Vice President Architecture and the Architects in David Castro-Blanco FAIA, Vice President Education Committees are co Tuesday, March 28. The Professional Douglas Korves AIA, Vice President Stephen P. -

The Studio Homes of Daniel Chester French by Karen Zukowski

SPRING 2018 Volume 25, No. 1 NEWSLETTER City/Country: The Studio Homes of Daniel Chester French by karen zukowski hat can the studios of Daniel Chester French (1850–1931) tell us about the man who built them? He is often described as a Wsturdy American country boy, practically self-taught, who, due to his innate talent and sterling character, rose to create the most heroic of America’s heroic sculptures. French sculpted the seated figure in Washington, D.C.’s Lincoln Memorial, which is, according to a recent report, the most popular statue in the United States.1 Of course, the real story is more complex, and examination of French’s studios both compli- cates and expands our understanding of him. For most of his life, French kept a studio home in New York City and another in Massachusetts. This city/country dynamic was essential to his creative process. BECOMING AN ARTIST French came of age as America recovered from the trauma of the Civil War and slowly prepared to become a world power. He was born in 1850 to an established New England family of gentleman farmers who also worked as lawyers and judges and held other leadership positions in civic life. French’s father was a lawyer who eventually became assistant secretary of the U.S. Treasury under President Grant. Dan (as his family called him) came to his profession while they were living in Concord, Massachusetts. This was the town renowned for plain living and high thinking, the home of literary giants Amos Bronson Alcott, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Nathaniel Hawthorne, and Henry David Thoreau at Walden Pond nearby. -

Menotomy Indian Hunter Fountain Evaluation

Ms. Clarissa Rowe Chair Arlington Community Preservation Commission Town of Arlington 730 Massachusetts Ave. Arlington, MA 02476 Dear Ms. Rowe Thank you for considering The Friends of the Robbins Town Garden application for a CPA grant to restore the garden’s water features. While we recognize that we are making a sizeable request, we feel that this project is of paramount importance to the town and the community. We hope that you agree. Once the fountain is restored, the town and our organization intend to continue to partner to ensure that the fountain is maintained so that such extensive repairs will never again be required. Our commitment to the garden extends beyond the restoration of the fountain. We have already raised more than $2,000 which we plan to spend this coming Spring to begin replacing some of the trees and plants that appear in the garden master plan but have been lost over the years. We hope that restoring the fountain will be an initial step to garnering additional support for further improvements in the garden. Our application outlines the history and historical significance of the Robbins Town Garden. It explains why the restoration of the central fountain is so essential to the town and its’ citizens and describes the broad range of local residents and people from surrounding communities who derive enjoyment from the garden. As an indication of the strong community support for our petition, our application mentions some of the many organizations and individuals who regularly help maintain the garden and whose members use the garden for celebrations, rest and relaxation. -

2425 Hermon Atkins Macneil, 1866

#2425 Hermon Atkins MacNeil, 1866-1947. Papers, [1896-l947J-1966. These additional papers include a letter from William Henry Fox, Secretary General of the U.S. Commission to the International Exposition of Art and History at Rome, Italy, in 1911, informing MacNeil that the King of Italy, Victor Emmanuel III, is interested in buying his statuette "Ai 'Primitive Chant", letters notifying MacNeil that he has been made an honorary member of the American Institute of Architects (1928) and a fellow of the AmRrican Numismatic Society (1935) and the National Sculpture Society (1946); letters of congratulation upon his marriage to Mrs. Cecelia W. Muench in 1946; an autobiographical sketch (20 pp. typescript carbon, 1943), certificates and citations from the National Academy of Design, the National Institute of Arts and letters, the Architectural League of New York, and the Disabled American Veterans of the World War, forty-eight photographs (1896+) mainly of the artist and his sculpture, newspaper clippings on his career, and miscellaneous printed items. Also, messages of condolence and formal tri butes sent to his widow (1947-1948), obituaries, and press reports (1957, 1966) concerning a memorial established for the artist. Correspondents include A. J. Barnouw, Emile Brunet, Jo Davidson, Carl Paul Jennewein, Leon Kroll, and many associates, relatives, and friends. £. 290 items. Maim! entry: Cross references to main entry: MacNeil, Hermon Atkins, 1866-1947. Barnouw, Adrian Jacob, 1877- Papers, [1896-l947J-1966. Brunet, Emile, 1899- Davidson, Jo, 1883-1951 Fox, William Henry Jennewein, Carl Paul, 1890- Kroll, Leon, 1884- Muench, Cecelia W Victor Emmanuel III, 1869-1947 See also detailed checklists on file in this folder. -

February 2021

February 2021 BEGIN TRANSCRIPT Welcome to the Dayton Art Institute Object of the Month presentation for February 2021. My name is Rick Hoffman and I’m a Museum Guide. I’d like to share with you one of my favorite statues in the museum’s collection, Chief Massasoit, by Cyrus Edwin Dallin, an American sculptor who lived from 1861 to 1944. He was famous for his depictions of Native Americans and patriotic figures like Paul Revere. This statue is eleven and a half feet tall, the tallest figurative sculpture in the museum. Why do you think that the artist created this piece so large? Chief Massasoit played a very important role in the survival of the pilgrims and the shared celebration of 1621, which led to the modern-day holiday of Thanksgiving. He helped maintain peace between the pilgrims and the Wampanoag Confederacy for over forty years until he died. So, we can surmise that Dallin rendered him this way to indicate the importance that the Chief played in American history. His statue is in fact very much larger than life size. Chief Massasoit was a grand sachem or leader of the Wampanoag Confederacy and he lived from 1581 to 1661. Ousamequin, or Yellow Feather in the native tongue of the Pokanoket tribe of modern-day Rhode Island and Massachusetts—his village was located where the town of Warren, Rhode Island is now. Let’s stand back and take a long look at this statue. He wears a simple deerskin, fringed loincloth, three beaded necklaces, and has a fringed leather pouch that hangs on his left side. -

Mayor's Office of Arts, Tourism and Special Events Boston Art

Mayor’s Office of Arts, Tourism and Special Events Boston Art Commission 100 Public Artworks: Back Bay, Beacon Hill, the Financial District and the North End 1. Lief Eriksson by Anne Whitney This life-size bronze statue memorializes Lief Eriksson, the Norse explorer believed to be the first European to set foot on North America. Originally sited to overlook the Charles River, Eriksson stands atop a boulder and shields his eyes as if surveying unfamiliar terrain. Two bronze plaques on the sculpture’s base show Eriksson and his crew landing on a rocky shore and, later, sharing the story of their discovery. When Boston philanthropist Eben N. Horsford commissioned the statue, some people believed that Eriksson and his crew landed on the shore of Massachusetts and founded their settlement, called Vinland, here. However, most scholars now consider Vinland to be located on the Canadian coast. This piece was created by a notable Boston sculptor, Anne Whitney. Several of her pieces can be found around the city. Whitney was a fascinating and rebellious figure for her time: not only did she excel in the typically ‘masculine’ medium of large-scale sculpture, she also never married and instead lived with a female partner. 2. Ayer Mansion Mosaics by Louis Comfort Tiffany At first glance, the Ayer Mansion seems to be a typical Back Bay residence. Look more closely, though, and you can see unique elements decorating the mansion’s façade. Both inside and outside, the Ayer Mansion is ornamented with colorful mosaics and windows created by the famed interior designer Louis Comfort Tiffany. -

The Flâneuse's Old Age

Universiteit Gent Academiejaar 2005 Women’s Passages: A Bildungsroman of Female Flânerie Verhandeling voorgelegd aan de Faculteit Letteren en Wijsbegeerte Promotor: Prof. Dr. Bart Keunen voor het verkrijgen van de graad van licentiaat in de taal- en letterkunde: Germaanse Talen, door (Karen Van Godtsenhoven). Credits: The writing of a dissertation requires a lot more than just a computer and books: apart from the many material and practical necessities, there still are many personal and difficult-to- trace advices, inspiring conversations and cityscapes that have helped me writing this little volume. This list cannot be inclusive, but I can try to track down the most relevant people, in their most relevant environment (in the line of the following chapters…). First of all, I want to thank all the people of the University of Ghent, for their help and interest from the very beginning. My promotor, Prof. Bart Keunen, wins the first prize for valuable advice and endless patience with my writings and my person. Other professors and teachers like Claire Vandamme, Bart Eeckhout, Elke Gilson and Katrien De Moor were good mentors and gave me lots of reading material and titles. From my former universities, I want to thank Prof. Martine de Clercq (KUBrussel) who helped me putting things together in an inspiring way. Other thank you’s go to Prof. Kate McGowan (Critical and Cultural Theory) and Prof. Angela Michaelis (Culture of Decadence) from the Manchester Metropolitan University, who gave me a more academic basis for my interest in the subject of this dissertation. I want to thank Petra Broeders from Passaporta in Brussels for lending me books and providing me with coffee, Guido Fourrier from the Fashion Museum in Hasselt for his refreshing tour of the A la Garçonne exhibition, the people from Rosa in Brussels for explaining me several gender issues, and Belle and Carolien from DASQ (Ghent) for their “decadent” literature salons where I had the opportunity to listen and talk to Denise De Weerdt. -

Lincoln Park

Panel 1 Panel 2 Panel 3 Panel 4 POINTS OF INTEREST LINCOLN PARK COME TO JOHANN WOLFGANG VON JOHN PETER ALTGELD LIGHT PEACE AND JUSTICE GOETHE MONUMENT MONUMENT 1 5 11 12 EMANUEL SWEDENBORG The stunning Margo McMahon produced Herman Hahn sculpted this This sculpture memorializes SHAKESPEARE MEMORIAL bricolage this sculpture owned by Soka enormous figure in 1910 of a Illinois’ first foreign-born 14 MONUMENT mosaic at Kathy Gakkai International, a world- young man holding an eagle governor, John Peter Altgeld, who The bronze portrait bust of 18 William Ordway Osterman wide network of lay Buddhists on his knee, to pay homage to spearheaded progressive reforms. Emanuel Swedenborg, produced ict r Partridge’s sculpture of Beach consists that has one of its headquarters the famous German writer and Created by John Gutzon de la by Swedish sculptor Adolf Jonnson William Shakespeare, of thousands in Chicago. The organization is philosopher Johann Wolfgang Mothe Borglum, one of America’s and dedicated in 1924, was stolen ©2014 Chicago Park District which portrays the of tile pieces. dedicated to a common vision von Goethe. most famous sculptors, the and never recovered. The Chicago playwright and poet Lead artist Andy Bellomo worked for more than of a better world through the monument was installed on Labor Park District replicated the missing in Elizabethan period a year and a half with other artists, community empowerment of the individual Day in 1915. bust in 2012 using the original 8 HUG CHICAGO clothing, was dedicated volunteers, and students on this project. and the promotion of peace, plaster model that had recently Highlighting Chicago’s diversity, the Hug Chicago in April 1894.