Reframing Partition: Memory, Testimony, History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No. Email id Remarks 20001 MUDKONDWAR SHRUTIKA HOSPITAL, TAHSIL Male 9420020369 [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 PRASHANT NAMDEORAO OFFICE ROAD, AT/P/TAL- GEORAI, 431127 BEED Maharashtra 20002 RADHIKA BABURAJ FLAT NO.10-E, ABAD MAINE Female 9886745848 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 PLAZA OPP.CMFRI, MARINE 8281300696 DRIVE, KOCHI, KERALA 682018 Kerela 20003 KULKARNI VAISHALI HARISH CHANDRA RESEARCH Female 0532 2274022 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 MADHUKAR INSTITUTE, CHHATNAG ROAD, 8874709114 JHUSI, ALLAHABAD 211019 ALLAHABAD Uttar Pradesh 20004 BICHU VAISHALI 6, KOLABA HOUSE, BPT OFFICENT Female 022 22182011 / NOT RENEW SHRIRANG QUARTERS, DUMYANE RD., 9819791683 COLABA 400005 MUMBAI Maharashtra 20005 DOSHI DOLLY MAHENDRA 7-A, PUTLIBAI BHAVAN, ZAVER Female 9892399719 [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 ROAD, MULUND (W) 400080 MUMBAI Maharashtra 20006 PRABHU SAYALI GAJANAN F1,CHINTAMANI PLAZA, KUDAL Female 02362 223223 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 OPP POLICE STATION,MAIN ROAD 9422434365 KUDAL 416520 SINDHUDURG Maharashtra 20007 RUKADIKAR WAHEEDA 385/B, ALISHAN BUILDING, Female 9890346988 DR.NAUSHAD.INAMDAR@GMA RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 BABASAHEB MHAISAL VES, PANCHIL NAGAR, IL.COM MEHDHE PLOT- 13, MIRAJ 416410 SANGLI Maharashtra 20008 GHORPADE TEJAL A-7 / A-8, SHIVSHAKTI APT., Male 02312650525 / NOT RENEW CHANDRAHAS GIANT HOUSE, SARLAKSHAN 9226377667 PARK KOLHAPUR Maharashtra 20009 JAIN MAMTA -

Lover Archetype in Punjabi Classical Poetry

The ‘Lover’ Archetype in Punjabi Classical Poetry Azra Waqar∗ Abstract Archetypes are primitive mental images which we encounter in art, literature and sacred text and they evoke a deep feeling within us. The most important archetypes represent four dimensions of personality to four levels of awareness and functions with one archetype for each gender. Archetypes can help us better understand our own journey of life, increase communication between our conscious and unconscious and trigger a greater sense of meaning and fulfilment in life. Archetypes first appear in folklore, in characters and symbols as they are a part of our collective unconscious. In Punjabi classical poetry, Ranjha, the lover is the archetype who represents love. He is the main character in the poetry of Shah Hussain, Bulleh Shah and Waris Shah. The poetry of these three poets are discussed in the following article, representing Ranjha, (the lover), as an essential part of our lives. The lover feels something missing in the society or in his life and leaves home and becomes a traveller. The main theme of the poetry of these three classical Punjabi poets is the story of his journey and his encounter with different obstacles in the way of finding love and beauty. An archetype is a primitive mental image inherited from the earliest human ancestors, is supposed to be present in the collective ∗ Former, Senior Research Fellow, National Institute of Historical and Cultural Research, Centre of Excellence, Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad. 132 Pakistan Journal of History and Culture, Vol.XXX, No.1 (2009) unconscious and serves as an example of human behaviour by which we can better understand ourselves and those around us. -

Exploring the Dynamics of Urban Development with Agent-Based Modeling

EXPLORING THE DYNAMICS OF URBAN DEVELOPMENT WITH AGENT- BASED MODELING: THE CASE OF PAKISTANI CITIES by Ammar A. Malik A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of George Mason University in Partial Fulfillment of The Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Public Policy Committee: Hilton L. Root, Chair Jonathan L. Gifford Andrew T. Crooks Harvey Galper, External Reader Kenneth Button, Program Director Mark Rozell, Dean Date: Spring Semester 2015 George Mason University Fairfax, VA Exploring the Dynamics of Urban Development with Agent-based Modeling: The Case of Pakistani Cities A Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at George Mason University by Ammar A. Malik Master of Public Affairs Institut d’Etudes Politiques (Sciences Po) Paris Director: Hilton L. Root, Professor School of Policy, Government, and International Affairs Spring Semester 2015 George Mason University Fairfax, VA This work is licensed under a creative commons attribution-noderivs 3.0 unported license. ii DEDICATION This dissertation is dedicated to my loving wife, Hira. I could not have completed this project without her consistent encouragement and support. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost, I am grateful to my parents, Atiq and Mamuna Malik, who provided the platform on which my life is based. They gave me the moral grounding and confidence to pursue my dreams. My two children, Nuha and Mahad Malik, were the source of ultimate joy and satisfaction. Their presence in my life kept me motivated and ensured that I remained true to my goals. My late paternal grandfather, Brigadier Bashir Malik, who left us during the first year of my journey. -

Folkloristic Understandings of Nation-Building in Pakistan

Folkloristic Understandings of Nation-Building in Pakistan Ideas, Issues and Questions of Nation-Building in Pakistan Research Cooperation between the Hanns Seidel Foundation Pakistan and the Quaid-i-Azam University Islamabad Islamabad, 2020 Folkloristic Understandings of Nation-Building in Pakistan Edited by Sarah Holz Ideas, Issues and Questions of Nation-Building in Pakistan Research Cooperation between Hanns Seidel Foundation, Islamabad Office and Quaid-i-Azam University Islamabad, Pakistan Acknowledgements Thank you to Hanns Seidel Foundation, Islamabad Office for the generous and continued support for empirical research in Pakistan, in particular: Kristóf Duwaerts, Omer Ali, Sumaira Ihsan, Aisha Farzana and Ahsen Masood. This volume would not have been possible without the hard work and dedication of a large number of people. Sara Gurchani, who worked as the research assistant of the collaboration in 2018 and 2019, provided invaluable administrative, organisational and editorial support for this endeavour. A big thank you the HSF grant holders of 2018 who were not only doing their own work but who were also actively engaged in the organisation of the international workshop and the lecture series: Ibrahim Ahmed, Fateh Ali, Babar Rahman and in particular Adil Pasha and Mohsinullah. Thank you to all the support staff who were working behind the scenes to ensure a smooth functioning of all events. A special thanks goes to Shafaq Shafique and Muhammad Latif sahib who handled most of the coordination. Thank you, Usman Shah for the copy editing. The research collaboration would not be possible without the work of the QAU faculty members in the year 2018, Dr. Saadia Abid, Dr. -

Saadat Hasan Manto

Saadat Hasan Manto -issues, from local to global are revealed in his series, Let دت :Saadat Hasan Manto (/mɑːn, -tɒ/; Urdu , pronounced [sa'ādat 'hasan 'maṅṭō]; 11 May 1912 – ters to Uncle Sam, and those to Pandit Nehru.[3] On his 18 January 1955) was a Pakistani writer, playwright and writing he often commented, “If you find my stories dirty, author considered among the greatest writers of short sto- the society you are living in is dirty. With my stories, I ries in South Asian history. He produced 22 collections only expose the truth”.[12] of short stories, 1 novel, 5 series of radio plays, 3 collec- tions of essays, 2 collections of personal sketches[1] and his best short stories are held in high esteem by writers and critics. 2 Biography Manto was tried for obscenity six times; thrice before 1947 in British India, and thrice after independence in 2.1 Early life and education 1947 in Pakistan, but never convicted.[2] Saadat Hassan Manto was born in Paproudi village of Samrala, in the Ludhiana district of the Punjab in a Mus- [13][14] 1 Writings lim family of barristers on 11 May 1912. The big turning point in his life came in 1933, at age 21,[15] when he met Abdul Bari Alig, a scholar and Manto chronicled the chaos that prevailed, during and [3][4] polemic writer, in Amritsar.Abdul Bari Alig encouraged after the Partition of India in 1947. He started his him to find his true talents and read Russian and French literary career translating work of literary giants, such authors.[16] as Victor Hugo, Oscar Wilde and Russian writers such as Chekhov and Gorky. -

A Synopsis Mystical Symbolism in Poetry: a Study of the Selected Works of Baba Farid, Guru Nanak Dev, Bulleh Shah and Waris Shah

A Synopsis Mystical Symbolism in Poetry: A Study of the Selected Works of Baba Farid, Guru Nanak Dev, Bulleh Shah and Waris Shah With Special Reference to: Sri Guru Granth Sahib Bulleh Shah Waris Shah’s Heer: A Rustic Epic of the Punjab A Synopsis Submitted for the Award of the Degree of the DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in English Supervisor: Submitted by: Dr. Gur Pyari Jandial Avneet Kaur Associate Professor Dept. Of English Studies Head of the Department: Dean: Prof. S. K. Chauhan Prof. Urmila Anand Dept. of English Studies Faculty of Arts Department Of English Studies Faculty of Arts Dayalbagh Educational Institute (Deemed University) Dayalbagh, Agra- 282110 1 Worship me in the symbols and images which remind thee of me. Srimad Bhagavatam, xi.v. The term „mysticism‟ has its origin in Neo – Platonism. It was derived from the Greek word mystikos which means „to initiate‟. This meant the initiation towards spiritual truth and experiences. In philosophy as stated by the “Catholic Encyclopaedia”, mysticism refers to the “desire of the human soul towards an intimate union with the Divinity.”1 Though it may sound ambiguous but mysticism brings a man closer to himself and takes him to those undiscovered realms which lie within himself. William James in his renowned book “The Varieties of Religious Experience” states: …our normal waking consciousness, rational consciousness as we call it, is but one special type of consciousness, whilst all about it, parted from it by the filmiest of screens, there lie potential forms of consciousness entirely different. We may go through life without suspecting their existence, but supply the requisite stimulus and at a touch they are there. -

List of Category -I Members Registered in Membership Drive-Ii

LIST OF CATEGORY -I MEMBERS REGISTERED IN MEMBERSHIP DRIVE-II MEMBERSHIP CGN QUOTA CATEGORY NAME DOB BPS CNIC DESIGNATION PARENT OFFICE DATE MR. DAUD AHMAD OIL AND GAS DEVELOPMENT COMPANY 36772 AUTONOMOUS I 25-May-15 BUTT 01-Apr-56 20 3520279770503 MANAGER LIMITD MR. MUHAMMAD 38295 AUTONOMOUS I 26-Feb-16 SAGHIR 01-Apr-56 20 6110156993503 MANAGER SOP OIL AND GAS DEVELOPMENT CO LTD MR. MALIK 30647 AUTONOMOUS I 22-Jan-16 MUHAMMAD RAEES 01-Apr-57 20 3740518930267 DEPUTY CHIEF MANAGER DESTO DY CHEIF ENGINEER CO- PAKISTAN ATOMIC ENERGY 7543 AUTONOMOUS I 17-Apr-15 MR. SHAUKAT ALI 01-Apr-57 20 6110119081647 ORDINATOR COMMISSION 37349 AUTONOMOUS I 29-Jan-16 MR. ZAFAR IQBAL 01-Apr-58 20 3520222355873 ADD DIREC GENERAL WAPDA MR. MUHAMMA JAVED PAKISTAN BORDCASTING CORPORATION 88713 AUTONOMOUS I 14-Apr-17 KHAN JADOON 01-Apr-59 20 611011917875 CONTRALLER NCAC ISLAMABAD MR. SAIF UR REHMAN 3032 AUTONOMOUS I 07-Jul-15 KHAN 01-Apr-59 20 6110170172167 DIRECTOR GENRAL OVERS PAKISTAN FOUNDATION MR. MUHAMMAD 83637 AUTONOMOUS I 13-May-16 MASOOD UL HASAN 01-Apr-59 20 6110163877113 CHIEF SCIENTIST PROFESSOR PAKISTAN ATOMIC ENERGY COMMISION 60681 AUTONOMOUS I 08-Jun-15 MR. LIAQAT ALI DOLLA 01-Apr-59 20 3520225951143 ADDITIONAL REGISTRAR SECURITY EXCHENGE COMMISSION MR. MUHAMMAD CHIEF ENGINEER / PAKISTAN ATOMIC ENERGY 41706 AUTONOMOUS I 01-Feb-16 LATIF 01-Apr-59 21 6110120193443 DERECTOR TRAINING COMMISSION MR. MUHAMMAD 43584 AUTONOMOUS I 16-Jun-15 JAVED 01-Apr-59 20 3820112585605 DEPUTY CHIEF ENGINEER PAEC WASO MR. SAGHIR UL 36453 AUTONOMOUS I 23-May-15 HASSAN KHAN 01-Apr-59 21 3520227479165 SENOR GENERAL MANAGER M/O PETROLEUM ISLAMABAD MR. -

States of Affect: Trauma in Partition/Post-Partition South Asia

STATES OF AFFECT: TRAUMA IN PARTITION/POST-PARTITION SOUTH ASIA By Rituparna Mitra A DISSERTATION Submitted to Michigan State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of English – Doctor of Philosophy 2015 ABSTRACT STATES OF AFFECT: TRAUMA IN PARTITION/POST-PARTITION SOUTH ASIA By Rituparna Mitra The Partition of the Indian subcontinent – into India and Pakistan in 1947 – was one of the crucial moments marking the break between the colonial and postcolonial era. My project is invested in exploring the Partition not merely in terms of the events of August 1947, but as an ongoing process that continues to splinter political, cultural, emotional and sexual life-worlds in South Asia. My dissertation seeks to map analytical pathways to locate the Partition and the attendant formations of minoritization and sectarian violence as continuing, unfolding processes that constitute postcolonial nation-building. It examines the far-reaching presence of these formations in current configurations of politics, culture and subjectivity by mobilizing the interdisciplinary scope of affect-mediated Trauma and Memory Studies and Postcolonial Studies, in conjunction with literary analysis. My project draws on a wide range of cultural artifacts such as poetry, cantillatory performance, mourning rituals, testimonials, archaeological ruins, short stories and novels to develop a heuristic and affective re-organization of post-Partition South Asia. It seeks to illuminate through frameworks of memory, melancholia, trauma, affect and postcoloniality how the ongoing effects of the past shape the present, which in turn, offers us ways to reimagine the future. This dissertation reaches out to recent work developing a vernacular framework to analyze violence, trauma and loss in South Asia. -

Saturday, 26 April 2014 Friday, 25 April 2014

Friday, 25 April 2014 5.00 – 9.00 p.m. Margala Hall Inauguration Welcome Speeches by Ameena Saiyid and Asif Farrukhi Keynote Speeches by Zehra Nigah and Aamer Hussein Performance by Sheema Kermani Dastangoi by Danish Husain and Darain Shahidi of India and Fawad Khan and Nazrul Hasan of NAPA Saturday, 26 April 2014 Margala Hall Sangam Hall Central Lawn Board Room Consulate Room In Conversation with Novel kay Nayay Rung: Children’s Literature is Book Launch: Feryal Ali-Gauhar Readings and Conversation with No Child’s Play! I’ll Find My Way: An Anthology Moderator: Ritu Menon Mirza Athar Baig and Launch of Saman Shamsie, Rumana Husain, of Short Stories Hassan ki Soorat-e-Haal: Khaali and Fauzia Minallah Edited by Maniza Naqvi Jaghain Pur Karo Moderator: Amra Alam Rehana Hyder and Framji Minwalla 10.00 – 11.00 a.m. Moderator: Irfan Javed Moderator: Irshad Abdul Kadir The De Factor: Jis Tarha Sookhay Huay Phool Afghanistan: The Next Chapter Book Launch: Labyrinth of Reflections: In Conversation with Shobhaa De Kitabon main Milay: Faraz ko Rashed Rahman, Sarwar Naqvi, The Waters of Lahore In Conversation with Rashid Rana Moderator: Aliya Iqbal-Naqvi Yaad Karnay kay Bahanay Tariq Osman Hyder, and by Kamal Azfar Moderator: Quddus Mirza Screening of Short Film on Faraz Najmuddin Shaikh Riaz H. Khokhar 12.15 p.m. and Discussion – Moderator: Rasul Bakhsh Rais Moderator: Shaheen Khattak Presented by ArtNow Shibli Faraz, Zehra Nigah, Kishwar Naheed, and Abid Hasan Minto 11.15 a.m. Moderator: Muhammad Ahmed Shah Drama and the Small Screen In Conversation with Intizar Mission Possible: Book Launch: Sultana Siddiqui, Sarmad Khoosat, Husain and Launch of Reforming State Schools What’s Wrong with Pakistan? Sahira Kazmi, and Apni Danist Main and Mosharraf Zaidi, Ameena Saiyid, by Babar Ayaz Asghar Nadeem Syed Safar kay Khush Naseeb Abbas Rashid, Nauman Naqvi, and Moderator: Zahid Hussain 1.30 p.m. -

Supplemental Statement Washington, DC 20530 Pursuant to the Foreign Agents Registration Act of 1938, As Amended

Received by NSD/FARA Registration Unit 07/17/2013 12:53:25 PM OMB NO. 1124-0002; Expires February 28, 2014 «JJ.S. Department of Justice Supplemental Statement Washington, DC 20530 Pursuant to the Foreign Agents Registration Act of 1938, as amended For Six Month Period Ending 06/30/2013 (Insert date) I - REGISTRANT 1. (a) Name of Registrant (b) Registration No. Pakistan Tehreek e Insaf 5975 (c) Business Address(es) of Registrant 315 Maple street Richardson TX, 75081 Has there been a change in the information previously furnished in connection with the following? (a) If an individual: (1) Residence address(es) Yes Q No D (2) Citizenship Yes Q No Q (3) Occupation Yes • No D (b) If an organization: (1) Name Yes Q No H (2) Ownership or control Yes • No |x] - (3) Branch offices Yes D No 0 (c) Explain fully all changes, if any, indicated in Items (a) and (b) above. IF THE REGISTRANT IS AN INDIVIDUAL, OMIT RESPONSE TO ITEMS 3,4, AND 5(a). 3. If you have previously filed Exhibit C1, state whether any changes therein have occurred during this 6 month reporting period. Yes D No H If yes, have you filed an amendment to the Exhibit C? Yes • No D If no, please attach the required amendment. I The Exhibit C, for which no printed form is provided, consists of a true copy of the charter, articles of incorporation, association, and by laws of a registrant that is an organization. (A waiver of the requirement to file an Exhibit C may be obtained for good cause upon written application to the Assistant Attorney General, National Security Division, U.S. -

Bulleh-Nickname.Pdf

YouTube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Rxc6v9XdOkA - ا را ُ : ُ ه bulleh shah: mera raanjhan: pathaney khan Mark A. Foster, Ph.D. YouTube Mix - bulleh shah: mera raanjhan: pathaney hafeez jalandhari: abhi to mein jawaan: malika pukhraj by KhamoshTamashai 48,341 views shah hussain: maaey ni ه ن: mein: hamid ali bela by KhamoshTamashai 49,618 views shah hussain: maaey ni ه ن mein: pathaney khan by KhamoshTamashai 8,791 views bulleh shah: punjabi poetry: ُ ه : م: pathaney khan by KhamoshTamashai 87,052 views را ران ُن : ُ ه bulleh shah: mera raanjhan: pathaney khan ghulam farid: meda ishq vi: وا م رد: pathaney khan KhamoshTamashai · 323 videos 74,574 by KhamoshTamashai 163,714 views 109 6 heer waris shah by ghulam ر وارث ه از م ali 1 Download About by KhamoshTamashai 70,400 views Uploaded on Mar 28, 2009 Buy "Mera Ranjhan Hun Koye" saiful maluk by inayat ف اﻟوک از was born c. 1680 in village Uchch on hussain bhatti 1 د ه The Poet: Abdullah Shah ت ن currently in Punjab, Google Play byّ KhamoshTamashai) وﻟور in Bahawalpur اچ ں Gilanian ّ Pakistan). Since Abdullah is called Bullah ُ in rural Punjabi, he AmazonMP3 151,349 views or Bullah . His father was Shah ه was called Bulleh Shah who was well educated in Soofi Poetry 2 , ه ّد دروش Muhammad Darwaish Arabic, Farsi, and the Quran. His ancestors immigrated from Artist by sohailbutt67 currently in Uzbekistan). When Bulleh Shah was Pathaney Khan) را Bukhara now) وال about six months old, his parents relocated to Malakwal ام There his father was an imam masjid .( وال in District Sahiwal person who leads prayers) in the village mosque and a kaalam baba bulle shah , toh) د ishg dee nahin gal janda , ڈو ّں teacher. -

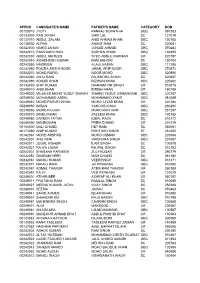

Appno Candidate's Name Father's Name Category Dob

APPNO CANDIDATE'S NAME FATHER'S NAME CATEGORY DOB 00120010 JYOTI PANKAJ TEWATHIA OBC 091283 00133030 RAN SINGH SHIV LAL SC 121079 00137010 ABDUL SALAM ANIS AHMAD KHAN OBC 150785 00138030 ALPNA ANANT RAM SC 220681 00242000 NAHID JAHAN JUNAID AHMAD OBC 070482 00242010 RAMZAAN KHAN SUBHAN KHAN OBC 160885 00242030 ABDUL MATEEN SYED ABDUL RAHMAN UR 020787 00242040 AWADHESH KUMAR RAM BAHORI SC 130784 00242050 NAZREEN ALAULHASAN OBC 111185 00242060 FOUZIA ARSHI NOOR JAMAL ARIF NOOR OBC 270872 00242070 MOHD RAFIQ NOOR MOHD OBC 020980 00242080 ANJU RANI RAJENDRA SINGH SC 020887 00242090 KOSAR KHAN RIZWAN KHAN OBC 220682 00143020 SHIV KUMAR DHARAM VIR SINGH UR 010878 00249010 ANIS KHAN IDRISH KHAN UR 190789 00249020 MUJAHID MOHD YUSUF SHAIKH SHAIKH YUSUF USMANGANI OBC 220787 00249030 MOHAMMAD ADEEL MOHAMMAD ZAKIR OBC 081089 00249040 MOHD PARVEJ KHAN MOHD ILIYAS KHAN UR 020184 00249050 IMRAN YAKOOB KHAN OBC 230284 00249060 MOHD RIJUAN MOHD RAFI ARIF OBC 251287 00249070 BINDU KHAN SALEEM KHAN OBC 160785 00249080 ZAHEEN FATMA IQBAL RAZA SC 010172 00249090 MANMOHAN PREM CHAND UR 201279 00166000 DULI CHAND HET RAM SC 030681 00173080 ANIP KUMAR ROHTASH SINGH ST 231085 00142061 MOHD ARSHAD MOHD USMAN OBC 220686 00242001 ANU RANI VIRENDRA SINGH OBC 201087 00242011 JUGAL KISHOR ILAM SINGH SC 100578 00242021 RAJYA LAXMI RAJPAL SINGH SC 010783 00242031 SHABANA PARVEEN ZULFAQQAR UR 290779 00242051 DHARAM VEER MAM CHAND SC 061180 00242061 MANOJ KUMAR VEERSINGH OBC 010171 00242071 MANJU RANI JAI PRAKASH OBC 010585 00242081 KOMAL THAKUR ATMA RAM THAKUR UR 260388