Mathematical Logic and Computability Contents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Verifying the Unification Algorithm In

Verifying the Uni¯cation Algorithm in LCF Lawrence C. Paulson Computer Laboratory Corn Exchange Street Cambridge CB2 3QG England August 1984 Abstract. Manna and Waldinger's theory of substitutions and uni¯ca- tion has been veri¯ed using the Cambridge LCF theorem prover. A proof of the monotonicity of substitution is presented in detail, as an exam- ple of interaction with LCF. Translating the theory into LCF's domain- theoretic logic is largely straightforward. Well-founded induction on a complex ordering is translated into nested structural inductions. Cor- rectness of uni¯cation is expressed using predicates for such properties as idempotence and most-generality. The veri¯cation is presented as a series of lemmas. The LCF proofs are compared with the original ones, and with other approaches. It appears di±cult to ¯nd a logic that is both simple and exible, especially for proving termination. Contents 1 Introduction 2 2 Overview of uni¯cation 2 3 Overview of LCF 4 3.1 The logic PPLAMBDA :::::::::::::::::::::::::: 4 3.2 The meta-language ML :::::::::::::::::::::::::: 5 3.3 Goal-directed proof :::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 6 3.4 Recursive data structures ::::::::::::::::::::::::: 7 4 Di®erences between the formal and informal theories 7 4.1 Logical framework :::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 8 4.2 Data structure for expressions :::::::::::::::::::::: 8 4.3 Sets and substitutions :::::::::::::::::::::::::: 9 4.4 The induction principle :::::::::::::::::::::::::: 10 5 Constructing theories in LCF 10 5.1 Expressions :::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: -

Pst-Plot — Plotting Functions in “Pure” L ATEX

pst-plot — plotting functions in “pure” LATEX Commonly, one wants to simply plot a function as a part of a LATEX document. Using some postscript tricks, you can make a graph of an arbitrary function in one variable including implicitly defined functions. The commands described on this worksheet require that the following lines appear in your document header (before \begin{document}). \usepackage{pst-plot} \usepackage{pstricks} The full pstricks manual (including pst-plot documentation) is available at:1 http://www.risc.uni-linz.ac.at/institute/systems/documentation/TeX/tex/ A good page for showing the power of what you can do with pstricks is: http://www.pstricks.de/.2 Reverse Polish Notation (postfix notation) Reverse polish notation (RPN) is a modification of polish notation which was a creation of the logician Jan Lukasiewicz (advisor of Alfred Tarski). The advantage of these notations is that they do not require parentheses to control the order of operations in an expression. The advantage of this in a computer is that parsing a RPN expression is trivial, whereas parsing an expression in standard notation can take quite a bit of computation. At the most basic level, an expression such as 1 + 2 becomes 12+. For more complicated expressions, the concept of a stack must be introduced. The stack is just the list of all numbers which have not been used yet. When an operation takes place, the result of that operation is left on the stack. Thus, we could write the sum of all integers from 1 to 10 as either, 12+3+4+5+6+7+8+9+10+ or 12345678910+++++++++ In both cases the result 55 is left on the stack. -

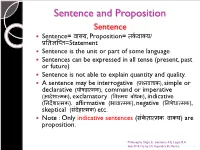

Logic- Sentence and Propositions

Sentence and Proposition Sentence Sentence= वा啍य, Proposition= त셍कवा啍य/ प्रततऻप्तत=Statement Sentence is the unit or part of some language. Sentences can be expressed in all tense (present, past or future) Sentence is not able to explain quantity and quality. A sentence may be interrogative (प्रश्नवाच셍), simple or declarative (घोषड़ा配म셍), command or imperative (आदेशा配म셍), exclamatory (ववमयतबोध셍), indicative (तनदेशा配म셍), affirmative (भावा配म셍), negative (तनषेधा配म셍), skeptical (संदेहा配म셍) etc. Note : Only indicative sentences (सं셍ेता配म셍तवा啍य) are proposition. Philosophy Dept, E- contents-01( Logic-B.A Sem.III & IV) by Dr Rajendra Kr.Verma 1 All kind of sentences are not proposition, only those sentences are called proposition while they will determine or evaluate in terms of truthfulness or falsity. Sentences are governed by its own grammar. (for exp- sentence of hindi language govern by hindi grammar) Sentences are correct or incorrect / pure or impure. Sentences are may be either true or false. Philosophy Dept, E- contents-01( Logic-B.A Sem.III & IV) by Dr Rajendra Kr.Verma 2 Proposition Proposition are regarded as the material of our reasoning and we also say that proposition and statements are regarded as same. Proposition is the unit of logic. Proposition always comes in present tense. (sentences - all tenses) Proposition can explain quantity and quality. (sentences- cannot) Meaning of sentence is called proposition. Sometime more then one sentences can expressed only one proposition. Example : 1. ऩानीतबरसतरहातहैत.(Hindi) 2. ऩावुष तऩड़तोत (Sanskrit) 3. It is raining (English) All above sentences have only one meaning or one proposition. -

Axiomatic Set Teory P.D.Welch

Axiomatic Set Teory P.D.Welch. August 16, 2020 Contents Page 1 Axioms and Formal Systems 1 1.1 Introduction 1 1.2 Preliminaries: axioms and formal systems. 3 1.2.1 The formal language of ZF set theory; terms 4 1.2.2 The Zermelo-Fraenkel Axioms 7 1.3 Transfinite Recursion 9 1.4 Relativisation of terms and formulae 11 2 Initial segments of the Universe 17 2.1 Singular ordinals: cofinality 17 2.1.1 Cofinality 17 2.1.2 Normal Functions and closed and unbounded classes 19 2.1.3 Stationary Sets 22 2.2 Some further cardinal arithmetic 24 2.3 Transitive Models 25 2.4 The H sets 27 2.4.1 H - the hereditarily finite sets 28 2.4.2 H - the hereditarily countable sets 29 2.5 The Montague-Levy Reflection theorem 30 2.5.1 Absoluteness 30 2.5.2 Reflection Theorems 32 2.6 Inaccessible Cardinals 34 2.6.1 Inaccessible cardinals 35 2.6.2 A menagerie of other large cardinals 36 3 Formalising semantics within ZF 39 3.1 Definite terms and formulae 39 3.1.1 The non-finite axiomatisability of ZF 44 3.2 Formalising syntax 45 3.3 Formalising the satisfaction relation 46 3.4 Formalising definability: the function Def. 47 3.5 More on correctness and consistency 48 ii iii 3.5.1 Incompleteness and Consistency Arguments 50 4 The Constructible Hierarchy 53 4.1 The L -hierarchy 53 4.2 The Axiom of Choice in L 56 4.3 The Axiom of Constructibility 57 4.4 The Generalised Continuum Hypothesis in L. -

Propositional Logic

Propositional Logic - Review Predicate Logic - Review Propositional Logic: formalisation of reasoning involving propositions Predicate (First-order) Logic: formalisation of reasoning involving predicates. • Proposition: a statement that can be either true or false. • Propositional variable: variable intended to represent the most • Predicate (sometimes called parameterized proposition): primitive propositions relevant to our purposes a Boolean-valued function. • Given a set S of propositional variables, the set F of propositional formulas is defined recursively as: • Domain: the set of possible values for a predicate’s Basis: any propositional variable in S is in F arguments. Induction step: if p and q are in F, then so are ⌐p, (p /\ q), (p \/ q), (p → q) and (p ↔ q) 1 2 Predicate Logic – Review cont’ Predicate Logic - Review cont’ Given a first-order language L, the set F of predicate (first-order) •A first-order language consists of: formulas is constructed inductively as follows: - an infinite set of variables Basis: any atomic formula in L is in F - a set of predicate symbols Inductive step: if e and f are in F and x is a variable in L, - a set of constant symbols then so are the following: ⌐e, (e /\ f), (e \/ f), (e → f), (e ↔ f), ∀ x e, ∃ s e. •A term is a variable or a constant symbol • An occurrence of a variable x is free in a formula f if and only •An atomic formula is an expression of the form p(t1,…,tn), if it does not occur within a subformula e of f of the form ∀ x e where p is a n-ary predicate symbol and each ti is a term. -

First Order Logic and Nonstandard Analysis

First Order Logic and Nonstandard Analysis Julian Hartman September 4, 2010 Abstract This paper is intended as an exploration of nonstandard analysis, and the rigorous use of infinitesimals and infinite elements to explore properties of the real numbers. I first define and explore first order logic, and model theory. Then, I prove the compact- ness theorem, and use this to form a nonstandard structure of the real numbers. Using this nonstandard structure, it it easy to to various proofs without the use of limits that would otherwise require their use. Contents 1 Introduction 2 2 An Introduction to First Order Logic 2 2.1 Propositional Logic . 2 2.2 Logical Symbols . 2 2.3 Predicates, Constants and Functions . 2 2.4 Well-Formed Formulas . 3 3 Models 3 3.1 Structure . 3 3.2 Truth . 4 3.2.1 Satisfaction . 5 4 The Compactness Theorem 6 4.1 Soundness and Completeness . 6 5 Nonstandard Analysis 7 5.1 Making a Nonstandard Structure . 7 5.2 Applications of a Nonstandard Structure . 9 6 Sources 10 1 1 Introduction The founders of modern calculus had a less than perfect understanding of the nuts and bolts of what made it work. Both Newton and Leibniz used the notion of infinitesimal, without a rigorous understanding of what they were. Infinitely small real numbers that were still not zero was a hard thing for mathematicians to accept, and with the rigorous development of limits by the likes of Cauchy and Weierstrass, the discussion of infinitesimals subsided. Now, using first order logic for nonstandard analysis, it is possible to create a model of the real numbers that has the same properties as the traditional conception of the real numbers, but also has rigorously defined infinite and infinitesimal elements. -

Unification: a Multidisciplinary Survey

Unification: A Multidisciplinary Survey KEVIN KNIGHT Computer Science Department, Carnegie-Mellon University, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania 15213-3890 The unification problem and several variants are presented. Various algorithms and data structures are discussed. Research on unification arising in several areas of computer science is surveyed, these areas include theorem proving, logic programming, and natural language processing. Sections of the paper include examples that highlight particular uses of unification and the special problems encountered. Other topics covered are resolution, higher order logic, the occur check, infinite terms, feature structures, equational theories, inheritance, parallel algorithms, generalization, lattices, and other applications of unification. The paper is intended for readers with a general computer science background-no specific knowledge of any of the above topics is assumed. Categories and Subject Descriptors: E.l [Data Structures]: Graphs; F.2.2 [Analysis of Algorithms and Problem Complexity]: Nonnumerical Algorithms and Problems- Computations on discrete structures, Pattern matching; Ll.3 [Algebraic Manipulation]: Languages and Systems; 1.2.3 [Artificial Intelligence]: Deduction and Theorem Proving; 1.2.7 [Artificial Intelligence]: Natural Language Processing General Terms: Algorithms Additional Key Words and Phrases: Artificial intelligence, computational complexity, equational theories, feature structures, generalization, higher order logic, inheritance, lattices, logic programming, natural language -

Operations Per Se, to See If the Proposed Chi Is Indeed Fruitful

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 204 124 SE 035 176 AUTHOR Weaver, J. F. TTTLE "Addition," "Subtraction" and Mathematical Operations. 7NSTITOTION. Wisconsin Univ., Madison. Research and Development Center for Individualized Schooling. SPONS AGENCY Neional Inst. 1pf Education (ED), Washington. D.C. REPORT NO WIOCIS-PP-79-7 PUB DATE Nov 79 GRANT OS-NIE-G-91-0009 NOTE 98p.: Report from the Mathematics Work Group. Paper prepared for the'Seminar on the Initial Learning of Addition and' Subtraction. Skills (Racine, WI, November 26-29, 1979). Contains occasional light and broken type. Not available in hard copy due to copyright restrictions.. EDPS PRICE MF01 Plum Postage. PC Not Available from EDRS. DEseR.TPT00S *Addition: Behavioral Obiectives: Cognitive Oblectives: Cognitive Processes: *Elementary School Mathematics: Elementary Secondary Education: Learning Theories: Mathematical Concepts: Mathematics Curriculum: *Mathematics Education: *Mathematics Instruction: Number Concepts: *Subtraction: Teaching Methods IDENTIFIERS *Mathematics Education ResearCh: *Number 4 Operations ABSTRACT This-report opens by asking how operations in general, and addition and subtraction in particular, ante characterized for 'elementary school students, and examines the "standard" Instruction of these topics through secondary. schooling. Some common errors and/or "sloppiness" in the typical textbook presentations are noted, and suggestions are made that these probleks could lend to pupil difficulties in understanding mathematics. The ambiguity of interpretation .of number sentences of the VW's "a+b=c". and "a-b=c" leads into a comparison of the familiar use of binary operations with a unary-operator interpretation of such sentences. The second half of this document focuses on points of vier that promote .varying approaches to the development of mathematical skills and abilities within young children. -

Hyperoperations and Nopt Structures

Hyperoperations and Nopt Structures Alister Wilson Abstract (Beta version) The concept of formal power towers by analogy to formal power series is introduced. Bracketing patterns for combining hyperoperations are pictured. Nopt structures are introduced by reference to Nept structures. Briefly speaking, Nept structures are a notation that help picturing the seed(m)-Ackermann number sequence by reference to exponential function and multitudinous nestings thereof. A systematic structure is observed and described. Keywords: Large numbers, formal power towers, Nopt structures. 1 Contents i Acknowledgements 3 ii List of Figures and Tables 3 I Introduction 4 II Philosophical Considerations 5 III Bracketing patterns and hyperoperations 8 3.1 Some Examples 8 3.2 Top-down versus bottom-up 9 3.3 Bracketing patterns and binary operations 10 3.4 Bracketing patterns with exponentiation and tetration 12 3.5 Bracketing and 4 consecutive hyperoperations 15 3.6 A quick look at the start of the Grzegorczyk hierarchy 17 3.7 Reconsidering top-down and bottom-up 18 IV Nopt Structures 20 4.1 Introduction to Nept and Nopt structures 20 4.2 Defining Nopts from Nepts 21 4.3 Seed Values: “n” and “theta ) n” 24 4.4 A method for generating Nopt structures 25 4.5 Magnitude inequalities inside Nopt structures 32 V Applying Nopt Structures 33 5.1 The gi-sequence and g-subscript towers 33 5.2 Nopt structures and Conway chained arrows 35 VI Glossary 39 VII Further Reading and Weblinks 42 2 i Acknowledgements I’d like to express my gratitude to Wikipedia for supplying an enormous range of high quality mathematics articles. -

Self-Similarity in the Foundations

Self-similarity in the Foundations Paul K. Gorbow Thesis submitted for the degree of Ph.D. in Logic, defended on June 14, 2018. Supervisors: Ali Enayat (primary) Peter LeFanu Lumsdaine (secondary) Zachiri McKenzie (secondary) University of Gothenburg Department of Philosophy, Linguistics, and Theory of Science Box 200, 405 30 GOTEBORG,¨ Sweden arXiv:1806.11310v1 [math.LO] 29 Jun 2018 2 Contents 1 Introduction 5 1.1 Introductiontoageneralaudience . ..... 5 1.2 Introduction for logicians . .. 7 2 Tour of the theories considered 11 2.1 PowerKripke-Plateksettheory . .... 11 2.2 Stratifiedsettheory ................................ .. 13 2.3 Categorical semantics and algebraic set theory . ....... 17 3 Motivation 19 3.1 Motivation behind research on embeddings between models of set theory. 19 3.2 Motivation behind stratified algebraic set theory . ...... 20 4 Logic, set theory and non-standard models 23 4.1 Basiclogicandmodeltheory ............................ 23 4.2 Ordertheoryandcategorytheory. ...... 26 4.3 PowerKripke-Plateksettheory . .... 28 4.4 First-order logic and partial satisfaction relations internal to KPP ........ 32 4.5 Zermelo-Fraenkel set theory and G¨odel-Bernays class theory............ 36 4.6 Non-standardmodelsofsettheory . ..... 38 5 Embeddings between models of set theory 47 5.1 Iterated ultrapowers with special self-embeddings . ......... 47 5.2 Embeddingsbetweenmodelsofsettheory . ..... 57 5.3 Characterizations.................................. .. 66 6 Stratified set theory and categorical semantics 73 6.1 Stratifiedsettheoryandclasstheory . ...... 73 6.2 Categoricalsemantics ............................... .. 77 7 Stratified algebraic set theory 85 7.1 Stratifiedcategoriesofclasses . ..... 85 7.2 Interpretation of the Set-theories in the Cat-theories ................ 90 7.3 ThesubtoposofstronglyCantorianobjects . ....... 99 8 Where to go from here? 103 8.1 Category theoretic approach to embeddings between models of settheory . -

Monadic Decomposition

Monadic Decomposition Margus Veanes1, Nikolaj Bjørner1, Lev Nachmanson1, and Sergey Bereg2 1 Microsoft Research {margus,nbjorner,levnach}@microsoft.com 2 The University of Texas at Dallas [email protected] Abstract. Monadic predicates play a prominent role in many decid- able cases, including decision procedures for symbolic automata. We are here interested in discovering whether a formula can be rewritten into a Boolean combination of monadic predicates. Our setting is quantifier- free formulas over a decidable background theory, such as arithmetic and we here develop a semi-decision procedure for extracting a monadic decomposition of a formula when it exists. 1 Introduction Classical decidability results of fragments of logic [7] are based on careful sys- tematic study of restricted cases either by limiting allowed symbols of the lan- guage, limiting the syntax of the formulas, fixing the background theory, or by using combinations of such restrictions. Many decidable classes of problems, such as monadic first-order logic or the L¨owenheim class [29], the L¨ob-Gurevich class [28], monadic second-order logic with one successor (S1S) [8], and monadic second-order logic with two successors (S2S) [35] impose at some level restric- tions to monadic or unary predicates to achieve decidability. Here we propose and study an orthogonal problem of whether and how we can transform a formula that uses multiple free variables into a simpler equivalent formula, but where the formula is not a priori syntactically or semantically restricted to any fixed fragment of logic. Simpler in this context means that we have eliminated all theory specific dependencies between the variables and have transformed the formula into an equivalent Boolean combination of predicates that are “essentially” unary. -

Mathematical Logic

Copyright c 1998–2005 by Stephen G. Simpson Mathematical Logic Stephen G. Simpson December 15, 2005 Department of Mathematics The Pennsylvania State University University Park, State College PA 16802 http://www.math.psu.edu/simpson/ This is a set of lecture notes for introductory courses in mathematical logic offered at the Pennsylvania State University. Contents Contents 1 1 Propositional Calculus 3 1.1 Formulas ............................... 3 1.2 Assignments and Satisfiability . 6 1.3 LogicalEquivalence. 10 1.4 TheTableauMethod......................... 12 1.5 TheCompletenessTheorem . 18 1.6 TreesandK¨onig’sLemma . 20 1.7 TheCompactnessTheorem . 21 1.8 CombinatorialApplications . 22 2 Predicate Calculus 24 2.1 FormulasandSentences . 24 2.2 StructuresandSatisfiability . 26 2.3 TheTableauMethod......................... 31 2.4 LogicalEquivalence. 37 2.5 TheCompletenessTheorem . 40 2.6 TheCompactnessTheorem . 46 2.7 SatisfiabilityinaDomain . 47 3 Proof Systems for Predicate Calculus 50 3.1 IntroductiontoProofSystems. 50 3.2 TheCompanionTheorem . 51 3.3 Hilbert-StyleProofSystems . 56 3.4 Gentzen-StyleProofSystems . 61 3.5 TheInterpolationTheorem . 66 4 Extensions of Predicate Calculus 71 4.1 PredicateCalculuswithIdentity . 71 4.2 TheSpectrumProblem . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 75 4.3 PredicateCalculusWithOperations . 78 4.4 Predicate Calculus with Identity and Operations . ... 82 4.5 Many-SortedPredicateCalculus . 84 1 5 Theories, Models, Definability 87 5.1 TheoriesandModels ......................... 87 5.2 MathematicalTheories. 89 5.3 DefinabilityoveraModel . 97 5.4 DefinitionalExtensionsofTheories . 100 5.5 FoundationalTheories . 103 5.6 AxiomaticSetTheory . 106 5.7 Interpretability . 111 5.8 Beth’sDefinabilityTheorem. 112 6 Arithmetization of Predicate Calculus 114 6.1 Primitive Recursive Arithmetic . 114 6.2 Interpretability of PRA in Z1 ....................114 6.3 G¨odelNumbers ............................ 114 6.4 UndefinabilityofTruth. 117 6.5 TheProvabilityPredicate .