Monadic Decomposition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Axiomatic Set Teory P.D.Welch

Axiomatic Set Teory P.D.Welch. August 16, 2020 Contents Page 1 Axioms and Formal Systems 1 1.1 Introduction 1 1.2 Preliminaries: axioms and formal systems. 3 1.2.1 The formal language of ZF set theory; terms 4 1.2.2 The Zermelo-Fraenkel Axioms 7 1.3 Transfinite Recursion 9 1.4 Relativisation of terms and formulae 11 2 Initial segments of the Universe 17 2.1 Singular ordinals: cofinality 17 2.1.1 Cofinality 17 2.1.2 Normal Functions and closed and unbounded classes 19 2.1.3 Stationary Sets 22 2.2 Some further cardinal arithmetic 24 2.3 Transitive Models 25 2.4 The H sets 27 2.4.1 H - the hereditarily finite sets 28 2.4.2 H - the hereditarily countable sets 29 2.5 The Montague-Levy Reflection theorem 30 2.5.1 Absoluteness 30 2.5.2 Reflection Theorems 32 2.6 Inaccessible Cardinals 34 2.6.1 Inaccessible cardinals 35 2.6.2 A menagerie of other large cardinals 36 3 Formalising semantics within ZF 39 3.1 Definite terms and formulae 39 3.1.1 The non-finite axiomatisability of ZF 44 3.2 Formalising syntax 45 3.3 Formalising the satisfaction relation 46 3.4 Formalising definability: the function Def. 47 3.5 More on correctness and consistency 48 ii iii 3.5.1 Incompleteness and Consistency Arguments 50 4 The Constructible Hierarchy 53 4.1 The L -hierarchy 53 4.2 The Axiom of Choice in L 56 4.3 The Axiom of Constructibility 57 4.4 The Generalised Continuum Hypothesis in L. -

Propositional Logic

Propositional Logic - Review Predicate Logic - Review Propositional Logic: formalisation of reasoning involving propositions Predicate (First-order) Logic: formalisation of reasoning involving predicates. • Proposition: a statement that can be either true or false. • Propositional variable: variable intended to represent the most • Predicate (sometimes called parameterized proposition): primitive propositions relevant to our purposes a Boolean-valued function. • Given a set S of propositional variables, the set F of propositional formulas is defined recursively as: • Domain: the set of possible values for a predicate’s Basis: any propositional variable in S is in F arguments. Induction step: if p and q are in F, then so are ⌐p, (p /\ q), (p \/ q), (p → q) and (p ↔ q) 1 2 Predicate Logic – Review cont’ Predicate Logic - Review cont’ Given a first-order language L, the set F of predicate (first-order) •A first-order language consists of: formulas is constructed inductively as follows: - an infinite set of variables Basis: any atomic formula in L is in F - a set of predicate symbols Inductive step: if e and f are in F and x is a variable in L, - a set of constant symbols then so are the following: ⌐e, (e /\ f), (e \/ f), (e → f), (e ↔ f), ∀ x e, ∃ s e. •A term is a variable or a constant symbol • An occurrence of a variable x is free in a formula f if and only •An atomic formula is an expression of the form p(t1,…,tn), if it does not occur within a subformula e of f of the form ∀ x e where p is a n-ary predicate symbol and each ti is a term. -

First Order Logic and Nonstandard Analysis

First Order Logic and Nonstandard Analysis Julian Hartman September 4, 2010 Abstract This paper is intended as an exploration of nonstandard analysis, and the rigorous use of infinitesimals and infinite elements to explore properties of the real numbers. I first define and explore first order logic, and model theory. Then, I prove the compact- ness theorem, and use this to form a nonstandard structure of the real numbers. Using this nonstandard structure, it it easy to to various proofs without the use of limits that would otherwise require their use. Contents 1 Introduction 2 2 An Introduction to First Order Logic 2 2.1 Propositional Logic . 2 2.2 Logical Symbols . 2 2.3 Predicates, Constants and Functions . 2 2.4 Well-Formed Formulas . 3 3 Models 3 3.1 Structure . 3 3.2 Truth . 4 3.2.1 Satisfaction . 5 4 The Compactness Theorem 6 4.1 Soundness and Completeness . 6 5 Nonstandard Analysis 7 5.1 Making a Nonstandard Structure . 7 5.2 Applications of a Nonstandard Structure . 9 6 Sources 10 1 1 Introduction The founders of modern calculus had a less than perfect understanding of the nuts and bolts of what made it work. Both Newton and Leibniz used the notion of infinitesimal, without a rigorous understanding of what they were. Infinitely small real numbers that were still not zero was a hard thing for mathematicians to accept, and with the rigorous development of limits by the likes of Cauchy and Weierstrass, the discussion of infinitesimals subsided. Now, using first order logic for nonstandard analysis, it is possible to create a model of the real numbers that has the same properties as the traditional conception of the real numbers, but also has rigorously defined infinite and infinitesimal elements. -

Self-Similarity in the Foundations

Self-similarity in the Foundations Paul K. Gorbow Thesis submitted for the degree of Ph.D. in Logic, defended on June 14, 2018. Supervisors: Ali Enayat (primary) Peter LeFanu Lumsdaine (secondary) Zachiri McKenzie (secondary) University of Gothenburg Department of Philosophy, Linguistics, and Theory of Science Box 200, 405 30 GOTEBORG,¨ Sweden arXiv:1806.11310v1 [math.LO] 29 Jun 2018 2 Contents 1 Introduction 5 1.1 Introductiontoageneralaudience . ..... 5 1.2 Introduction for logicians . .. 7 2 Tour of the theories considered 11 2.1 PowerKripke-Plateksettheory . .... 11 2.2 Stratifiedsettheory ................................ .. 13 2.3 Categorical semantics and algebraic set theory . ....... 17 3 Motivation 19 3.1 Motivation behind research on embeddings between models of set theory. 19 3.2 Motivation behind stratified algebraic set theory . ...... 20 4 Logic, set theory and non-standard models 23 4.1 Basiclogicandmodeltheory ............................ 23 4.2 Ordertheoryandcategorytheory. ...... 26 4.3 PowerKripke-Plateksettheory . .... 28 4.4 First-order logic and partial satisfaction relations internal to KPP ........ 32 4.5 Zermelo-Fraenkel set theory and G¨odel-Bernays class theory............ 36 4.6 Non-standardmodelsofsettheory . ..... 38 5 Embeddings between models of set theory 47 5.1 Iterated ultrapowers with special self-embeddings . ......... 47 5.2 Embeddingsbetweenmodelsofsettheory . ..... 57 5.3 Characterizations.................................. .. 66 6 Stratified set theory and categorical semantics 73 6.1 Stratifiedsettheoryandclasstheory . ...... 73 6.2 Categoricalsemantics ............................... .. 77 7 Stratified algebraic set theory 85 7.1 Stratifiedcategoriesofclasses . ..... 85 7.2 Interpretation of the Set-theories in the Cat-theories ................ 90 7.3 ThesubtoposofstronglyCantorianobjects . ....... 99 8 Where to go from here? 103 8.1 Category theoretic approach to embeddings between models of settheory . -

Mathematical Logic

Copyright c 1998–2005 by Stephen G. Simpson Mathematical Logic Stephen G. Simpson December 15, 2005 Department of Mathematics The Pennsylvania State University University Park, State College PA 16802 http://www.math.psu.edu/simpson/ This is a set of lecture notes for introductory courses in mathematical logic offered at the Pennsylvania State University. Contents Contents 1 1 Propositional Calculus 3 1.1 Formulas ............................... 3 1.2 Assignments and Satisfiability . 6 1.3 LogicalEquivalence. 10 1.4 TheTableauMethod......................... 12 1.5 TheCompletenessTheorem . 18 1.6 TreesandK¨onig’sLemma . 20 1.7 TheCompactnessTheorem . 21 1.8 CombinatorialApplications . 22 2 Predicate Calculus 24 2.1 FormulasandSentences . 24 2.2 StructuresandSatisfiability . 26 2.3 TheTableauMethod......................... 31 2.4 LogicalEquivalence. 37 2.5 TheCompletenessTheorem . 40 2.6 TheCompactnessTheorem . 46 2.7 SatisfiabilityinaDomain . 47 3 Proof Systems for Predicate Calculus 50 3.1 IntroductiontoProofSystems. 50 3.2 TheCompanionTheorem . 51 3.3 Hilbert-StyleProofSystems . 56 3.4 Gentzen-StyleProofSystems . 61 3.5 TheInterpolationTheorem . 66 4 Extensions of Predicate Calculus 71 4.1 PredicateCalculuswithIdentity . 71 4.2 TheSpectrumProblem . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 75 4.3 PredicateCalculusWithOperations . 78 4.4 Predicate Calculus with Identity and Operations . ... 82 4.5 Many-SortedPredicateCalculus . 84 1 5 Theories, Models, Definability 87 5.1 TheoriesandModels ......................... 87 5.2 MathematicalTheories. 89 5.3 DefinabilityoveraModel . 97 5.4 DefinitionalExtensionsofTheories . 100 5.5 FoundationalTheories . 103 5.6 AxiomaticSetTheory . 106 5.7 Interpretability . 111 5.8 Beth’sDefinabilityTheorem. 112 6 Arithmetization of Predicate Calculus 114 6.1 Primitive Recursive Arithmetic . 114 6.2 Interpretability of PRA in Z1 ....................114 6.3 G¨odelNumbers ............................ 114 6.4 UndefinabilityofTruth. 117 6.5 TheProvabilityPredicate . -

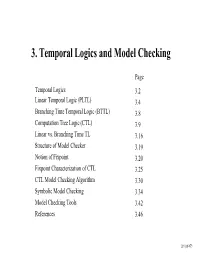

3. Temporal Logics and Model Checking

3. Temporal Logics and Model Checking Page Temporal Logics 3.2 Linear Temporal Logic (PLTL) 3.4 Branching Time Temporal Logic (BTTL) 3.8 Computation Tree Logic (CTL) 3.9 Linear vs. Branching Time TL 3.16 Structure of Model Checker 3.19 Notion of Fixpoint 3.20 Fixpoint Characterization of CTL 3.25 CTL Model Checking Algorithm 3.30 Symbolic Model Checking 3.34 Model Checking Tools 3.42 References 3.46 3.1 (of 47) Temporal Logics Temporal Logics • Temporal logic is a type of modal logic that was originally developed by philosophers to study different modes of “truth” • Temporal logic provides a formal system for qualitatively describing and reasoning about how the truth values of assertions change over time • It is appropriate for describing the time-varying behavior of systems (or programs) Classification of Temporal Logics • The underlying nature of time: Linear: at any time there is only one possible future moment, linear behavioral trace Branching: at any time, there are different possible futures, tree-like trace structure • Other considerations: Propositional vs. first-order Point vs. intervals Discrete vs. continuous time Past vs. future 3.2 (of 47) Linear Temporal Logic • Time lines Underlying structure of time is a totally ordered set (S,<), isomorphic to (N,<): Discrete, an initial moment without predecessors, infinite into the future. • Let AP be set of atomic propositions, a linear time structure M=(S, x, L) S: a set of states x: NS an infinite sequence of states, (x=s0,s1,...) L: S2AP labeling each state with the set of atomic propositions in AP true at the state. -

First-Order Logic

Lecture 14: First-Order Logic 1 Need For More Than Propositional Logic In normal speaking we could use logic to say something like: If all humans are mortal (α) and all Greeks are human (β) then all Greeks are mortal (γ). So if we have α = (H → M) and β = (G → H) and γ = (G → M) (where H, M, G are propositions) then we could say that ((α ∧ β) → γ) is valid. That is called a Syllogism. This is good because it allows us to focus on a true or false statement about one person. This kind of logic (propositional logic) was adopted by Boole (Boolean Logic) and was the focus of our lectures so far. But what about using “some” instead of “all” in β in the statements above? Would the statement still hold? (After all, Zeus had many children that were half gods and Greeks, so they may not necessarily be mortal.) We would then need to say that “Some Greeks are human” implies “Some Greeks are mortal”. Unfortunately, there is really no way to express this in propositional logic. This points out that we really have been abstracting out the concept of all in propositional logic. It has been assumed in the propositions. If we want to now talk about some, we must make this concept explicit. Also, we should be able to reason that if Socrates is Greek then Socrates is mortal. Also, we should be able to reason that Plato’s teacher, who is Greek, is mortal. First-Order Logic allows us to do this by writing formulas like the following. -

First Order Logic (Part I)

Logic: First Order Logic (Part I) Alessandro Artale Free University of Bozen-Bolzano Faculty of Computer Science http://www.inf.unibz.it/˜artale Descrete Mathematics and Logic — BSc course Thanks to Prof. Enrico Franconi for provoding the slides Alessandro Artale Logic: First Order Logic (Part I) Motivation We can already do a lot with propositional logic. But it is unpleasant that we cannot access the structure of atomic sentences. Atomic formulas of propositional logic are too atomic – they are just statement which may be true or false but which have no internal structure. In First Order Logic (FOL) the atomic formulas are interpreted as statements about relationships between objects. Alessandro Artale Logic: First Order Logic (Part I) Predicates and Constants Let’s consider the statements: Mary is female John is male Mary and John are siblings In propositional logic the above statements are atomic propositions: Mary-is-female John-is-male Mary-and-John-are-siblings In FOL atomic statements use predicates, with constants as argument: Female(mary) Male(john) Siblings(mary,john) Alessandro Artale Logic: First Order Logic (Part I) Variables and Quantifiers Let’s consider the statements: Everybody is male or female A male is not a female In FOL, predicates may have variables as arguments, whose value is bounded by quantifiers: ∀x. Male(x) ∨ Female(x) ∀x. Male(x) → ¬Female(x) Deduction (why?): Mary is not male ¬Male(mary) Alessandro Artale Logic: First Order Logic (Part I) Functions Let’s consider the statement: The father of a person is male In FOL objects of the domain may be denoted by functions applied to (other) objects: ∀x. -

Logic Taking a Step Back Some Modeling Paradigms Outline

Help Taking a step back Logic query Languages and expressiveness Propositional logic Specification of propositional logic data Learning model Inference Inference algorithms for propositional logic Inference in propositional logic with only definite clauses Inference in full propositional logic predictions Firstorder logic Specification of firstorder logic Models describe how the world works (relevant to some task) Inference algorithms for firstorder logic Inference in firstorder logic with only definite clauses What type of models? Inference in full firstorder logic Other logics Logic and probability CS221: Artificial Intelligence (Autumn 2012) Percy Liang CS221: Artificial Intelligence (Autumn 2012) Percy Liang 1 Some modeling paradigms Outline State space models: search problems, MDPs, games Languages and expressiveness Applications: route finding, game playing, etc. Propositional logic Specification of propositional logic Think in terms of states, actions, and costs Inference algorithms for propositional logic Variablebased models: CSPs, Markov networks, Bayesian Inference in propositional logic with only definite networks clauses Applications: scheduling, object tracking, medical diagnosis, etc. Inference in full propositional logic Think in terms of variables and factors Firstorder logic Specification of firstorder logic Logical models: propositional logic, firstorder logic Inference algorithms for firstorder logic Applications: proving theorems, program verification, reasoning Inference in firstorder logic with only -

Twenty Years of Topological Logic

Twenty Years of Topological Logic Ian Pratt-Hartmann Abstract Topological logics are formal systems for representing and manipulating information about the topological relationships between objects in space. Over the past two decades, these logics have been the subject of intensive research in Artificial Intelligence, under the general rubric of Qualitative Spatial Reasoning. This chapter sets out the mathematical foundations of topological logics, and surveys some of their many surprising properties. Keywords Spatial logic Qualitative spatial reasoning Artificial Intelligence Á Á 1 Introduction At about the time of Las Navas 1990, the first steps were being taken in a discipline that has since come to be called Qualitative Spatial Reasoning. The driving force behind these developments was the conviction that effective, commonsense, spatial reasoning requires representation languages with two related features: first, their variables should range over spatial regions; second, their non-logical—i.e. geo- metrical—primitives should express qualitative relations between those regions. In particular, the traditional conceptual scheme of coordinate geometry, where the only first-class geometrical objects are points, and where all geometrical relations are defined with reference to the coordinate positions of points, appeared unsuited to the rough-and-ready knowledge we have of spatial arrangements in our everyday surroundings. Such point-based, metrical representations—so it seemed—would I. Pratt-Hartmann (&) School of Computer Science, University of Manchester, Manchester M13 9PL, UK e-mail: [email protected] M. Raubal et al. (eds.), Cognitive and Linguistic Aspects of Geographic Space, 217 Lecture Notes in Geoinformation and Cartography, DOI: 10.1007/978-3-642-34359-9_12, Ó Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2013 218 I. -

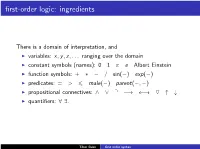

First Order Syntax

first-order logic: ingredients There is a domain of interpretation, and I variables: x; y; z;::: ranging over the domain I constant symbols (names): 0 1 π e Albert Einstein I function symbols: + ∗ − = sin(−) exp(−) I predicates: = > 6 male(−) parent(−; −) I propositional connectives: ^ _ q −! ! O "# I quantifiers: 8 9. Tibor Beke first order syntax False. sentences Let the domain of interpretation be the set of real numbers. 8a 8b 8c 9x(ax2 + bx + c = 0) This formula is an example of a sentence from first-order logic. It has no free variables: every one of the variables a, b, c, x is in the scope of a quantifier. A sentence has a well-defined truth value that can be discovered (at least, in principle). The sentence above (interpreted over the real numbers) is Tibor Beke first order syntax sentences Let the domain of interpretation be the set of real numbers. 8a 8b 8c 9x(ax2 + bx + c = 0) This formula is an example of a sentence from first-order logic. It has no free variables: every one of the variables a, b, c, x is in the scope of a quantifier. A sentence has a well-defined truth value that can be discovered (at least, in principle). The sentence above (interpreted over the real numbers) is False. Tibor Beke first order syntax \Every woman has two children " but is, in fact, logically equivalent to every woman having at least one child. That child could play the role of both y and z. sentences Let the domain of discourse be a set of people, let F (x) mean \x is female" and let P(x; y) mean \x is a parent of y". -

Chapter 6: Translations in Monadic Predicate Logic 223

TRANSLATIONS IN 6 MONADIC PREDICATE LOGIC 1. Introduction ....................................................................................................222 2. The Subject-Predicate Form of Atomic Statements......................................223 3. Predicates........................................................................................................224 4. Singular Terms ...............................................................................................226 5. Atomic Formulas ............................................................................................228 6. Variables And Pronouns.................................................................................230 7. Compound Formulas ......................................................................................232 8. Quantifiers ......................................................................................................232 9. Combining Quantifiers With Negation ..........................................................236 10. Symbolizing The Statement Forms Of Syllogistic Logic ..............................243 11. Summary of the Basic Quantifier Translation Patterns so far Examined ......248 12. Further Translations Involving Single Quantifiers ........................................251 13. Conjunctive Combinations of Predicates.......................................................255 14. Summary of Basic Translation Patterns from Sections 12 and 13.................262 15. ‘Only’..............................................................................................................263