IV. Undiscovered Tombs in the Valley(S) of the Kings by MICHAEL J MARFLEET

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

June 18 Newsletter

ESSEX EGYPTOLOGY GROUP Newsletter 114 June/July 2018 DATES FOR YOUR DIARY 3rd June The Tomb of Tatia at Saqqara: Vincent Oeters 1st July Papyrus Berlin P10480-82: a Middle Kingdom mortuary ritual reflected in writing: Dr Ilona Regulski 5th August Flies, lions and oysters: military awards or tea for two: Taneash Sidpura Annual General Meeting 2nd September Egypt’s Origins: the view from Mesopotamia and Iran: Dr Paul Collins This month we welcome back Vincent Oeters from Holland. During the 2009 field season of the joint mission of the Rijksmuseum van Oudheden (National Museum of Antiquities) at Leiden, the Netherlands and Leiden University (Faculty of Humanities, Department of Egyptology) a small Ramesside tomb-chapel was unearthed in the New Kingdom necropolis at Saqqara (1550-1070 BC), south of the causeway of Unas. The tomb-chapel belonged to a man named Tatia, Priest of the front of Ptah and Chief of the Goldsmiths. By studying the reliefs as well as the architecture and by comparing the tomb with other Ramesside tombs at Saqqara and elsewhere, an attempt was made to establish a more precise dating of the monument. Recent research has resulted in new insights on Tatia and his career, signs of private devotion and familial relationships. It appears Tatia was a relative of two other well-known New Kingdom officials, one whose important tomb was also built at Saqqara, the other a vizier and 'High Priest of Amun' in Thebes. In July we welcome, Ilona Regulski, the curator responsible for the papyrus collection and other inscribed material in the collection at the British Museum. -

Needle Roller and Cage Assemblies B-003〜022

*保持器付針状/B001-005_*保持器付針状/B001-005 11/05/24 20:31 ページ 1 Needle roller and cage assemblies B-003〜022 Needle roller and cage assemblies for connecting rod bearings B-023〜030 Drawn cup needle roller bearings B-031〜054 Machined-ring needle roller bearings B-055〜102 Needle Roller Bearings Machined-ring needle roller bearings, B-103〜120 BEARING TABLES separable Self-aligning needle roller bearings B-121〜126 Inner rings B-127〜144 Clearance-adjustable needle roller bearings B-145〜150 Complex bearings B-151〜172 Cam followers B-173〜217 Roller followers B-218〜240 Thrust roller bearings B-241〜260 Components Needle rollers / Snap rings / Seals B-261〜274 Linear bearings B-275〜294 One-way clutches B-295〜299 Bottom roller bearings for textile machinery Tension pulleys for textile machinery B-300〜308 *保持器付針状/B001-005_*保持器付針状/B001-005 11/05/24 20:31 ページ 2 B-2 *保持器付針状/B001-005_*保持器付針状/B001-005 11/05/24 20:31 ページ 3 Needle Roller and Cage Assemblies *保持器付針状/B001-005_*保持器付針状/B001-005 11/05/24 20:31 ページ 4 Needle roller and cage assemblies NTN Needle Roller and Cage Assemblies This needle roller and cage assembly is one of the or a housing as the direct raceway surface, without using basic components for the needle roller bearing of a inner ring and outer ring. construction wherein the needle rollers are fitted with a The needle rollers are guided by the cage more cage so as not to separate from each other. The use of precisely than the full complement roller type, hence this roller and cage assembly enables to design a enabling high speed running of bearing. -

Emission Station List by County for the Web

Emission Station List By County for the Web Run Date: June 20, 2018 Run Time: 7:24:12 AM Type of test performed OIS County Station Status Station Name Station Address Phone Number Number OBD Tailpipe Visual Dynamometer ADAMS Active 194 Imports Inc B067 680 HANOVER PIKE , LITTLESTOWN PA 17340 717-359-7752 X ADAMS Active Bankerts Auto Service L311 3001 HANOVER PIKE , HANOVER PA 17331 717-632-8464 X ADAMS Active Bankert'S Garage DB27 168 FERN DRIVE , NEW OXFORD PA 17350 717-624-0420 X ADAMS Active Bell'S Auto Repair Llc DN71 2825 CARLISLE PIKE , NEW OXFORD PA 17350 717-624-4752 X ADAMS Active Biglerville Tire & Auto 5260 301 E YORK ST , BIGLERVILLE PA 17307 -- ADAMS Active Chohany Auto Repr. Sales & Svc EJ73 2782 CARLISLE PIKE , NEW OXFORD PA 17350 717-479-5589 X 1489 CRANBERRY RD. , YORK SPRINGS PA ADAMS Active Clines Auto Worx Llc EQ02 717-321-4929 X 17372 611 MAIN STREET REAR , MCSHERRYSTOWN ADAMS Active Dodd'S Garage K149 717-637-1072 X PA 17344 ADAMS Active Gene Latta Ford Inc A809 1565 CARLISLE PIKE , HANOVER PA 17331 717-633-1999 X ADAMS Active Greg'S Auto And Truck Repair X994 1935 E BERLIN ROAD , NEW OXFORD PA 17350 717-624-2926 X ADAMS Active Hanover Nissan EG08 75 W EISENHOWER DR , HANOVER PA 17331 717-637-1121 X ADAMS Active Hanover Toyota X536 RT 94-1830 CARLISLE PK , HANOVER PA 17331 717-633-1818 X ADAMS Active Lawrence Motors Inc N318 1726 CARLISLE PIKE , HANOVER PA 17331 717-637-6664 X 630 HOOVER SCHOOL RD , EAST BERLIN PA ADAMS Active Leas Garage 6722 717-259-0311 X 17316-9571 586 W KING STREET , ABBOTTSTOWN PA ADAMS Active -

We're Archæologists, Not Grave Robbers!

We’re Archæologists, Not Gra ve Robbers! A Terra Incognita Ad venture, Egypt, 1908 by Ann Dupuis and Scott Larson Copyright ©2002 by Grey Ghost Press, Inc. Ancient tombs, precious artifacts, a race against time and rival archaeologists – you’ve done this before. But this time the tomb’s defenses may be your death.... But the prize, oh the prize! About Terra Incognita: Terra Incognita is a Victorian/Pulp roleplaying game from Grey Ghost Press, Inc. It follows the exploits of the National Archæological, Geographic, and Submarine Society, an organization of explorers and adventurers. The NAGS society’s public face is that of a stodgy society of would-be and have-been adventurers based in London, England. Behind the scenes, NAGS operatives from nearly every continent and culture travel to the four corners of the world, uncovering ancient mysteries and secrets. The Society studies and examines the ancient artifacts and knowledge so uncovered. If they deem the world is not yet ready for the secrets that had so long lain hidden, they cover them back up again. For more information about Terra Incognita, including pre-generated player characters that may be used with this adventure, please visit http://www.nagssociety.com. What’s Fudge? Fudge is a role-playing game for any genre, setting, or campaign. It’s designed to be modified for each Game Master’s needs and preferences. Terra Incognita uses a customized version of Fudge. You can get the full Fudge rules free on-line, at http://www.fudgerpg.com. Or buy the Fudge Expanded Edition from your Favorite Local Game Store! Backstory for "We’re Archaeologists!" Twenty years ago, in 1888, a group of Nags discovered, excavated, and explored an ancient Egyptian tomb in the Western branch of the Valley of the Kings. -

DS Forrsrejse 2007

DÆS forårsrejse 2007 - steder og personer Fredag 16.3 Dendera tempel: bl.a. stenblokke ved siden af fra MR mm., krypt og tag med zodiac (kopi, original på Louvre) Abydos: Seti Is tempel, Osireion bag Setis tempel og Ramses IIs tempel. Gode billeder på bla.: http://www.egyptarchive.co.uk/html/seti_abydos_index.html og http://www.egyptarchive.co.uk/html/ramesses_abydos_index.html Lørdag 17.3 Theben Vestbredden: Kongernes Dal: det nye Visitor Center med den japanske model af Kongernes Dal, Merneptahs grav KV8 og forskellige grave, bl.a. Tutmosis III KV33, Tausret/Sethnakht KV14, Seti II KV15, Siptah KV47, Ramses III KV11. Gåtur over bjergene fra Kongernes Dal til Deir el Medina, hvor nogle gik via arbejderhytterne. Glem ikke: http://www.kv5.com/ med alt om Kongernes Dal. Deir el Medina: Sennedjems grav TT1 og TT359 Inherkau - nogle så også/eller i stedet TT359 Pashedus grav TT3. Vi var rundt om selve arbejderbyen til det ptolemæiske Hathortempel, de mindre kapeller og den såkaldte ’Great Pit’, der var forsøg på at grave en kæmpe brønd. Der er fantastiske billeder og planer mm. af gravene på: http://www.osirisnet.net/tombes/artisans/e_artis1.htm Pause overfor Medinet Habu (Jørgen og Elsebeth forsøgte at finde et lille tempel i baghaven – jeg tror det må være Qasr el Aguz, som er et lille tempel bygget af Ptolemæus VII for Thoth (PMII, 527-530), se: http://www.egyptsites.co.uk/upper/luxorwest/temples/cult.html . - Tinne og Preben nåede lige et lynvisit i Medinet Habu!). Rekhmires grav TT100 og Sennefers grav TT96. Se også: http://www.osirisnet.net/tombes/nobles/e_nob1.htm med disse grave og mange flere! Søndag 18.3 Formiddag ’fri’, nogle i Karnak eller ved den nyligt frilagte Sfinxallé mm. -

119 Original Article the GOLDEN SHRINES of TUTANKHAMUN

id9070281 pdfMachine by Broadgun Software - a great PDF writer! - a great PDF creator! - http://www.pdfmachine.com http://www.broadgun.com Egyptian Journal of Archaeological and Restoration Studies "EJARS" An International peer-reviewed journal published bi-annually Volume 2, Issue 2, December - 2012: pp: 119-130 www. ejars.sohag-univ.edu.eg Original article THE GOLDEN SHRINES OF TUTANKHAMUN AND THEIR INTENDED BURIAL PLACE Soliman, R. Lecturer, Tourism guidance dept., Faculty of Archaeology & Tourism guidance, Misr Univ. for Sciences & Technology, 6th October city, Egypt E-mail: [email protected] Received 3/5/2012 Accepted 12/10/2012 Abstract The most famous tomb at the Valley of the Kings, KV 62 housed so far the most intact discovery of royal funerary treasures belonging to the eighteenth dynasty boy-king Tutankhamun. The tomb has a simple architectural plan clearly prepared for a non- royal burial. However, the hastily death of Tutankhamun at a young age caused his interment in such unusually small tomb. The treasures discovered were immense in number, art finesse and especially in the amount of gold used. Of these treasures the largest shrine of four shrines laid in the burial chamber needed to be dismantled and reassembled in the tomb because of its immense size. Clearly the black marks on this shrine helped in the assembly and especially the orientation in relation to the burial chamber. These marks are totally incorrect and prove that Tutankhamun was definitely intended to be buried in another tomb. Keywords: KV62, WV23, Golden shrines, Tutankhamun, Burial chamber, Orientation. 1. Introduction Tutankhamun was only nine and the real cause of his death remains years old when he got to throne; at that enigmatic. -

On the Modeling of Air Flow in the Tombs of the Valley of Kings

cs: O ani pe ch n e A c M c Khalil, Fluid Mech Open Acc 2017, 4:3 d e i s u s l F Fluid Mechanics: Open Access DOI: 10.4172/2476-2296.1000166 ISSN: 2476-2296 Research Article Open Access On the Modeling of Air Flow in the Tombs of the Valley of Kings Essam E Khalil1,2* 1Chairman Arab HVAC Code Committee ASHRAE Director-At-Large, USA, Convenor ISO TC205 WG2, Co-Convenor ISO TC163 WG4, Deputy Director (International) AIAA, USA 2DIC, Professor of Mechanical Engineering, Cairo University, Cairo, Egypt Abstract The tombs of the kings in Valley of the Kings, Luxor, are considered to be one of the tourism industry’s bases in Egypt due to their uniqueness all over the world. Hence, they should be preserved from the different factors that might cause harm for their wall paintings. One of these factors is the excessive relative humidity as it increases the bacteria and fungus activity inside the tomb in addition to its effect on the mechanical and physical properties of materials. This chapter describes the Research work to design ventilation systems to some of these important tombs. The chapter aims to investigate, design, and implement controlled climate to the tombs of the valley of kings with complete monitoring of air properties, temperature, relative humidity and carbon oxides and air quality parameters mechanical distributions inside selected tombs of the valley of the kings that are open for visitors. A complete climate control and monitoring of air will be effected with the aid of a mechanical ventilation system extracting air at designated locations in the wooden raised floor of the tombs. -

Il Cristianesimo in Egitto Luci E Ombre in Abydos La Tomba

egittologia.net magazine in questo numero: IL CRISTIANESIMO IN EGITTO EGITTO A VENEZIA LUCI E OMBRE IN ABYDOS SPECIALE NEFERTARI LA TOMBA QV66 AREA ARCHEOLOGICA TEBANA IL VILLAGGIO DI DEIR EL-MEDINA EGITTO IN PILLOLE ISCRIZIONI IERATICHE NELLA TOMBA DI THUTMOSI IV Italiani in Egitto: Ernesto Schiaparelli | L’Arte di Shamira | I papiri di Carla BOLLETTINO INFORMATIVO DELL'ASSOCIAZIONE EGITTOLOGIA.NET NUMERO 3 e d i t o r i a l e La prolungata e precoce presenza di questo Confesso che questo numero di EM – Egitto- insolito e intenso caldo, dà l’impressione che logia.net Magazine è stato sul punto di non l’estate stia già volgendo al termine, anche se uscire! La prossimità con il ferragosto e il in realtà la legna accumulata per l’inverno caldo scoraggiante, soprattutto nelle due set- dovrà aspettare ancora molto tempo prima di timane centrali del mese di luglio – periodo in essere utile. cui il terzo numero del magazine ha comin- Curioso come hanno deciso di chiamare le tre ciato a prendere vita – ci avevano fatto propen- fasi più intense del caldo i meteorologici: Sci- dere per una sospensione, procrastinandone pione, Caronte e Minosse. Curioso perché mi l’uscita direttamente a ottobre. vien da pensare che l’epiteto “Africano” di Sci- Ma abbiamo resistito alla tentazione, sospen- pione e il collegamento con l’Ade che è possi- dendo solo una parte dei temi che abbiamo bile fare con Caronte e Minosse, abbia cominciato a trattare nei numeri precedenti, richiamato alla mente degli scienziati il con- come ci è stato richiesto dagli autori degli cetto di “caldo”. -

Minnowenvironmental Inc

--~------- minnowenvironmental inc. _____ 2 Lamb Street Georgetown, Ontario L7G 3M9 Memorandum To: Dan Cornett, Access Consulting Group From: Cynthia Russel, Minnow Environmental Inc. Date: February 13, 2008-02-13 Re: Update of Surface Water Quality Assessment for United Keno Hill Mine Complex. Minnow Environmental Inc. (Minnow) was retained by Access Consulting Group to undertake an assessment of the existing water quality data for the United Keno Hill Mine Complex (United Keno, Galena and Sourdough Hill). The objective of this assessment was to identify parameters and locations of concern within the downstream waters relative to established guidelines and background. This information, combined with toxicity data and watershed use objectives may then be combined to develop an approach for considering the development of Site Specific Water Quality Objectives (SSWQO) for various parameters and locations. In order to meet the study objectives, a progressive assessment of the available water quality data was undertaken which included the following steps; • Screen all data to identify outliers (i.e., those greater then 3 standard deviations from the mean) and remove these data. • Establish the background concentration for each parameter based the upper limit of background data distribution (mean + t S.D.) for the combined data from KV-1 and KV-37. UKH Surface Water Quality Assessment - Progress Report • Identify parameters with high method detection limits relative to guidelines which preclude determination of whether concentrations exceed the guideline. • Identify background concentrations which exceed the Canadian Water Quality Guidelines (CWQG). • Determine the median, mean, minimum and maximum concentration for each parameter at each location. • Determine which locations exceed background and/or CWQG at measurable (10%) and substantial (50%) frequencies. -

Geo-Environmental Monitoring and 3D Finite Elements Stability Analysis for Site Investigation of Horemheb Tomb (Kv57), Luxor, Egypt

Geo-Environmental Monitoring and 3D Finite Elements Stability Analysis for site Investigation of Horemheb Tomb (Kv57), Luxor, Egypt Sayed Hemeda ( [email protected] ) Cairo University Research Keywords: Geo-environmental investigation, Remote sensing, GIS, 3D Geotechnical Modeling, Thebes Formations, Esna shale, rock support structure, Horemheb tomb (KV57), Valley of the Kings, Rock cut tomb Posted Date: August 7th, 2020 DOI: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-45712/v1 License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Read Full License GEO-ENVIRONMENTAL MONITORING AND 3D FINITE ELEMENTS STABILITY ANALYSIS FOR SITE INVESTIGATION OF HOREMHEB TOMB (KV57), LUXOR, EGYPT. Sayed Hemeda Professor, Conservation Department, Faculty of Archaeology, Cairo University, Egypt. Fax: 0235728108. P.C 12613. email: [email protected] ORCID ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0308-9285 Abstract: The Valley of the Kings (KV) is a UNESCO world heritage site with more than thirty opened tombs. Recently, most of these tombs have been damaged and inundated after 1994 flood. The Pharaonic rock-cut tombs at the valley of kings at the west bank of Luxor, were excavated mainly in the lower member I of the Thebes Limestone Formations and Esna shale Formations. These underground structures show serve degrees of damage and disintegration of supporting rock pillars, sidewalls and ceilings. In order to understand the Geo-environmental impact mainly the past flash floods in particularly the 1994 flood due to the intensive rainfall storm on the valley of kings and the long-term rock mass behavior under geostatic stresses in selected Horemheb tomb (KV57) and its impact on past failures and current stability, Remote sensing, GIS, LIDAR, 3D finite element stability analysis and rock mass quality assessments had been carried out using advanced methods and codes. -

From the Delta to the Cataract Studies Dedicated to Mohamed El-Bialy

From the Delta to the Cataract Culture and History of the Ancient Near East Founding Editor M.H.E. Weippert Editor-in-Chief Jonathan Stökl Editors Eckart Frahm W. Randall Garr B. Halpern Theo P.J. van den Hout Leslie Anne Warden Irene J. Winter VOLUME 76 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/chan From the Delta to the Cataract Studies Dedicated to Mohamed el-Bialy Edited by Alejandro Jiménez-Serrano and Cornelius von Pilgrim LEIDEN | BOSTON From the delta to the cataract : studies dedicated to Mohamed el-Bialy / edited by Alejandro Jiménez-Serrano and Cornelius von Pilgrim. pages cm. — (Culture and history of the ancient Near East, ISSN 1566-2055 ; volume 76) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-90-04-29344-1 (hardback : acid-free paper) — ISBN 978-90-04-29345-8 (e-book) 1. Egypt— Antiquities. 2. Aswan (Egypt)—Antiquities. 3. Thebes (Egypt : Extinct city) 4. Excavations (Archaeology)— Egypt. 5. Excavations (Archaeology)—Egypt—Aswan. 6. El-Bialy, Mohamed, 1953– 7. Archaeologists— Egypt—Biography. 8. Cultural property—Protection—Egypt. 9. Archaeology—Research—Egypt. I. Jiménez Serrano, Alejandro. II. Pilgrim, Cornelius von. IIi. El-Bialy, Mohamed, 1953– DT60.F85 2015 932—dc23 2015007584 This publication has been typeset in the multilingual ‘Brill’ typeface. With over 5,100 characters covering Latin, ipa, Greek, and Cyrillic, this typeface is especially suitable for use in the humanities. For more information, please see brill.com/brill-typeface. issn 1566-2055 isbn 978-90-04-29344-1 (hardback) isbn 978-90-04-29345-8 (e-book) Copyright 2015 by Koninklijke Brill nv, Leiden, The Netherlands. -

DSFRA IKEN Report Template

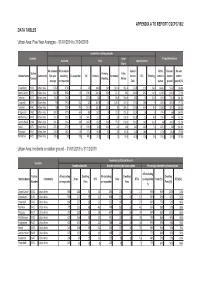

APPENDIX A TO REPORT CSCPC/19/2 DATA TABLES Urban Area: Five-Year Averages – 01/04/2014 to 31/04/2019 Incidents on station grounds Location False Pump Attendances Overview Fires Special Service Alarm All incidents All incidents Special All by On own On own Station Primary: False Station Name Community five-year excluding Co-responder All Primary Secondary Service RTC Flooding station's station station Number Dwelling Alarms average co-responder Calls pumps ground ground (%) Greenbank KV50 Urban Area 878.6 878.6 0 245 104.6 56.6 140.4 361.4 271.8 21.6 24.6 1424.8 974.2 68.4% Danes Castle KV32 Urban Area 832.6 830.8 1.8 198.8 126.4 56.6 72.4 385 248.4 29.2 14.8 1090.6 849.4 77.9% Torquay KV17 Urban Area 744.8 744.8 0 207.8 111 59 96.8 306.8 230 36 15.8 919.8 776.4 84.4% Crownhill KV49 Urban Area 742 741.8 0.2 227 100.6 43 126.4 337.4 177.4 28.6 9 878.4 680.6 77.5% Taunton KV61 Urban Area 734 733.4 0.6 227.8 132.8 56.6 95 284.6 221.6 65.4 8.4 1038.8 901.8 86.8% Bridgwater KV62 Urban Area 584.2 577.6 6.6 160 88.2 38 71.8 231.8 192.4 56 8 774.4 666 86.0% Middlemoor KV59 Urban Area 537.6 535.8 1.8 144.2 91.2 33 53 239.6 153.8 51 8.8 724.4 444 61.3% Camels Head KV48 Urban Area 491.6 491.2 0.4 162.8 85.2 50.4 77.6 178.6 150.2 16.6 11.8 638 390.2 61.2% Yeovil KV73 Urban Area 471.6 471.6 0 139.6 78.6 34.8 61 191 141 46.8 7.4 674.2 569 84.4% Plympton KV47 Urban Area 218.4 204.4 14 57.8 34.8 12 23 87.8 72.4 18.6 3 170.6 135.8 79.6% Plymstock KV51 Urban Area 185.8 185 0.8 48.4 27.4 12 21 76.8 60.6 12.6 2.6 165.4 123.8 74.8% Urban Area: Incidents on