Indo 66 0 1106954794 159

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Indonesia Beyond Reformasi: Necessity and the “De-Centering” of Democracy

INDONESIA BEYOND REFORMASI: NECESSITY AND THE “DE-CENTERING” OF DEMOCRACY Leonard C. Sebastian, Jonathan Chen and Adhi Priamarizki* TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION: TRANSITIONAL POLITICS IN INDONESIA ......................................... 2 R II. NECESSITY MAKES STRANGE BEDFELLOWS: THE GLOBAL AND DOMESTIC CONTEXT FOR DEMOCRACY IN INDONESIA .................... 7 R III. NECESSITY-BASED REFORMS ................... 12 R A. What Necessity Inevitably Entailed: Changes to Defining Features of the New Order ............. 12 R 1. Military Reform: From Dual Function (Dwifungsi) to NKRI ......................... 13 R 2. Taming Golkar: From Hegemony to Political Party .......................................... 21 R 3. Decentralizing the Executive and Devolution to the Regions................................. 26 R 4. Necessary Changes and Beyond: A Reflection .31 R IV. NON NECESSITY-BASED REFORMS ............. 32 R A. After Necessity: A Political Tug of War........... 32 R 1. The Evolution of Legislative Elections ........ 33 R 2. The Introduction of Direct Presidential Elections ...................................... 44 R a. The 2004 Direct Presidential Elections . 47 R b. The 2009 Direct Presidential Elections . 48 R 3. The Emergence of Direct Local Elections ..... 50 R V. 2014: A WATERSHED ............................... 55 R * Leonard C. Sebastian is Associate Professor and Coordinator, Indonesia Pro- gramme at the Institute of Defence and Strategic Studies, S. Rajaratnam School of In- ternational Studies, Nanyang Technological University, -

A Review of Thee Kian Wie's Major

Economics and Finance in Indonesia Vol. 61 No. 1, 2015 : 41-52 p-ISSN 0126-155X; e-ISSN 2442-9260 41 The Indonesian Economy from the Colonial Extraction Period until the Post-New Order Period: A Review of Thee Kian Wie’s Major Works Maria Monica Wihardjaa,∗, Siwage Dharma Negarab,∗∗ aWorld Bank Office Jakarta bIndonesian Institute of Sciences (LIPI) Abstract This paper reviews some major works of Thee Kian Wie, one of Indonesia’s most distinguished economic historians, that spans from the Colonial period until the post-New Order period. His works emphasize that economic history can guide future economic policy. Current problems in Indonesia were resulted from past policy failures. Indonesia needs to consistently embark on open economic policies, free itself from "colonial period mentality". Investment should be made in rebuilding crumbling infrastructure, improving the quality of health and education services, and addressing poor law enforcement. If current corruption persists, Indone- sia could not hope to become a dynamic and prosperous country. Keywords: Economic History; Colonial Period; Industrialization; Thee Kian Wie Abstrak Tulisan ini menelaah beberapakarya besar Thee Kian Wie, salah satu sejarawan ekonomi paling terhormat di Indonesia, mulai dari periode penjajahan hingga periode pasca-Orde Baru. Karya Beliau menekankan bahwa sejarah ekonomi dapat memberikan arahan dalam perumusan kebijakan ekonomi mendatang. Permasalahan yang dihadapi Indonesia dewasa ini merupakan akibat kegagalan kebijakan masa lalu. In- donesia perlu secara konsisten menerapkan kebijakan ekonomi terbuka, membebaskan diri dari "mentalitas periode penjajahan". Investasi perlu ditingkatkan untuk pembangunan kembali infrastruktur, peningkatan kualitas layanan kesehatan dan pendidikan, serta pembenahan penegakan hukum. Jika korupsi saat ini berlanjut, Indonesia tidak dapat berharap untuk menjadi negara yang dinamis dan sejahtera. -

A US-Indonesia Partnership for 2020: Recommendations for Forging

A U.S.–Indonesia Partnership for 2020 Recommendations for Forging a 21st Century Relationship AUTHORS A Report of the CSIS Sumitro Murray Hiebert Chair for Southeast Asia Studies Ted Osius SEPTEMBER 2013 Gregory B. Poling A U.S.- Indonesia Partnership for 2020 Recommendations for Forging a 21st Century Relationship AUTHORS Murray Hiebert Ted Osius Gregory B. Poling A Report of the CSIS Sumitro Chair for Southeast Asia Studies September 2013 ROWMAN & LITTLEFIELD Lanham • Boulder • New York • Toronto • Plymouth, UK About CSIS— 50th Anniversary Year For 50 years, the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) has developed solutions to the world’s greatest policy challenges. As we celebrate this milestone, CSIS scholars are developing strategic insights and bipartisan policy solutions to help decisionmakers chart a course toward a better world. CSIS is a nonprofi t orga ni zation headquartered in Washington, D.C. The Center’s 220 full-time staff and large network of affi liated scholars conduct research and analysis and develop policy initiatives that look into the future and anticipate change. Founded at the height of the Cold War by David M. Abshire and Admiral Arleigh Burke, CSIS was dedicated to fi nding ways to sustain American prominence and prosperity as a force for good in the world. Since 1962, CSIS has become one of the world’s preeminent international institutions focused on defense and security; regional stability; and transnational challenges ranging from energy and climate to global health and economic integration. Former U.S. senator Sam Nunn has chaired the CSIS Board of Trustees since 1999. Former deputy secretary of defense John J. -

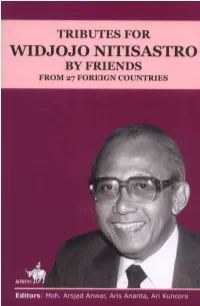

Tributes1.Pdf

Tributes for Widjojo Nitisastro by Friends from 27 Foreign Countries Law No.19 of 2002 regarding Copyrights Article 2: 1. Copyrights constitute exclusively rights for Author or Copyrights Holder to publish or copy the Creation, which emerge automatically after a creation is published without abridge restrictions according the law which prevails here. Penalties Article 72: 2. Anyone intentionally and without any entitlement referred to Article 2 paragraph (1) or Article 49 paragraph (1) and paragraph (2) is subject to imprisonment of no shorter than 1 month and/or a fine minimal Rp 1.000.000,00 (one million rupiah), or imprisonment of no longer than 7 years and/or a fine of no more than Rp 5.000.000.000,00 (five billion rupiah). 3. Anyone intentionally disseminating, displaying, distributing, or selling to the public a creation or a product resulted by a violation of the copyrights referred to under paragraph (1) is subject to imprisonment of no longer than 5 years and/or a fine of no more than Rp 500.000.000,00 (five hundred million rupiah). Tributes for Widjojo Nitisastro by Friends from 27 Foreign Countries Editors: Moh. Arsjad Anwar Aris Ananta Ari Kuncoro Kompas Book Publishing Jakarta, January 2007 Tributes for Widjojo Nitisastro by Friends from 27 Foreign Countries Published by Kompas Book Pusblishing, Jakarta, January 2007 PT Kompas Media Nusantara Jalan Palmerah Selatan 26-28, Jakarta 10270 e-mail: [email protected] KMN 70007006 Editor: Moh. Arsjad Anwar, Aris Ananta, and Ari Kuncoro Copy editor: Gangsar Sambodo and Bagus Dharmawan Cover design by: Gangsar Sambodo and A.N. -

Appendix 2 Intelligence Career Paths

Appendix 2 Intelligence career paths In this Appendix I will sketch the main groupings in the Indonesian intelligence world in the New Order period, and discuss what appear to be typical career groups and paths. This will, to some extent, mean covering ground already presented, but looked at from a slightly different angle. However, the detailed evidence for most of what I have to say here lies in the biographies of men involved in intelligence set out in Appendix 1.1 The three major divisions are obvious enough: a large number of military men against several small groups of significant civilians; the predominance of the Army against the other services; and generational groupings within the Army. Beyond these broad divisions, I will look at competing streams within the Army in the New Order period: Mainstream Army Intelligence and the Military Police streams; the career patterns of intelligence professionals under Moerdani; the role of combat/Special Forces officers in intelligence in the 1970s and 1980s; and the distinctions suggested in the 1970s between what have been called "principled" (or technocratic) versus "pragmatic" or manipulative approaches to intelligence agencies' political interventions. Military and civilian intelligence roles It is clear that the great bulk of intelligence posts since 1965, as well as before, have been filled by serving or retired military officers - it is a thoroughly militarized system. The principal intelligence organizations throughout the new Order period have either been military in nature, or, as in the case of Bakin, dominated at the higher levels by military officers. That said, let us begin this discussion by looking at the small number of civilians who do come into the picture at different times in the story. -

Yayasan-Yayasan Soeharto Oleh George Junus Aditjondro

Tempointeraktif.com - Yayasan-Yayasan Soeharto oleh George Junus Aditjondro Search | Advance search | Registration | About us | Careers dibuat oleh Radja:danendro Home Budaya Nasional Digital Berita Terkait Ekonomi Yayasan-Yayasan Soeharto oleh George Mahasiswa Serentak Kenang Tragedi Iptek • Junus Aditjondro Trisakti Jakarta Jum'at, 14 Mei 2004 | 19:23 WIB • Kesehatan Soeharto Memburuk Nasional • BEM Se-Yogya Tolak Mega, Akbar, Nusa TEMPO Interaktif : Wiranto, dan Tutut Olahraga • Asvi: Ada Polarisasi di Komnas HAM Majalah BERAPA sebenarnya kekayaan keluarga Suharto dari yayasan- soal Kasus Soeharto yayasan yang didirikan dan dipimpin Suharto dan Pemeriksaan Kesehatan Soeharto Koran • keluarganya, dari saham yayasan- yayasan itu dalam Belum Jelas Pusat Data berbagai konglomerat di Indonesia dan di luar negeri? • Kejaksaan Lanjutkan Perkara Setelah Tempophoto Soeharto Sehat Narasi Pertanyaan ini sangat sulit dijawab oleh "orang luar". LSM: Selidiki Pelanggaran HAM • English Kesulitan melacak kekayaan semua yayasan itu diperparah Soeharto oleh tumpang-tindihnya kekayaan keluarga Suharto dengan • Komnas HAM: Lima Pelanggaran HAM kekayaan sejumlah keluarga bisnis yang lain, misalnya tiga Berat di Masa Soeharto keluarga Liem Sioe Liong, keluarga Eka Tjipta Widjaya, dan • Pengacara Suharto: Kejari Kurang keluarga Bob Hasan. Kerjaan • Mahasiswa Mendemo KPU Tapi jangan difikir bahwa keluarga Suharto hanya senang >selengkapnya... menggunakan pengusaha-pengusaha keturunan Cina sebagai operator bisnisnya. Sebab bisnis keluarga Suharto juga sangat tumpang tindih dengan bisnis dua keluarga keturunan Referensi Arab, yakni Bakrie dan Habibie. Keluarga Bakrie segudang kongsinya dengan keluarga Suharto, a.l. dengan Bambang • Yayasan-Yayasan Soeharto oleh dan Sudwikatmono dalam bisnis minyak mentah Pertamina George Junus Aditjondro lewat Hong Kong (Pura, 1986; Toohey, 1990: 8-9; Warta • Biodata Soeharto Ekonomi , 30 Sept. -

Plagiat Merupakan Tindakan Tidak Terpuji Plagiat

PLAGIATPLAGIAT MERUPAKAN MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TIDAK TERPUJI TERPUJI PEMERINTAHAN PRESIDEN B.J. HABIBIE (1998-1999): KEBIJAKAN POLITIK DALAM NEGERI MAKALAH Diajukan untuk Memenuhi Salah Satu Syarat Memperoleh Gelar Sarjana Pendidikan Program Studi Pendidikan Sejarah Oleh: ALBERTO FERRY FIRNANDUS NIM: 101314023 PROGRAM STUDI PENDIDIKAN SEJARAH JURUSAN PENDIDIKAN ILMU PENGETAHUAN SOSIAL FAKULTAS KEGURUAN DAN ILMU PENDIDIKAN UNIVERSITAS SANATA DHARMA YOGYAKARTA 2015 PLAGIATPLAGIAT MERUPAKAN MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TIDAK TERPUJI TERPUJI PEMERINTAHAN PRESIDEN B.J. HABIBIE (1998-1999): KEBIJAKAN POLITIK DALAM NEGERI MAKALAH Diajukan untuk Memenuhi Salah Satu Syarat Memperoleh Gelar Sarjana Pendidikan Program Studi Pendidikan Sejarah Oleh: ALBERTO FERRY FIRNANDUS NIM: 101314023 PROGRAM STUDI PENDIDIKAN SEJARAH JURUSAN PENDIDIKAN ILMU PENGETAHUAN SOSIAL FAKULTAS KEGURUAN DAN ILMU PENDIDIKAN UNIVERSITAS SANATA DHARMA YOGYAKARTA 2015 i PLAGIATPLAGIAT MERUPAKAN MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TIDAK TERPUJI TERPUJI ii PLAGIATPLAGIAT MERUPAKAN MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TIDAK TERPUJI TERPUJI iii PLAGIATPLAGIAT MERUPAKAN MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TIDAK TERPUJI TERPUJI HALAMAN PERSEMBAHAN Makalah ini ku persembahkan kepada: Kedua orang tua ku yang selalu mendoakan dan mendukungku. Teman-teman yang selalu memberikan bantuan, semangat dan doa. Almamaterku. iv PLAGIATPLAGIAT MERUPAKAN MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TIDAK TERPUJI TERPUJI HALAMAN MOTTO Selama kita bersungguh-sungguh maka kita akan memetik buah yang manis, segala keputusan hanya ditangan kita sendiri, kita mampu untuk itu. (B.J. Habibie) Dimanapun engkau berada selalulah menjadi yg terbaik dan berikan yang terbaik dari yg bisa kita berikan. (B.J. Habibie) Pandanglah hari ini, kemarin sudah jadi mimpi. Dan esok hanyalah sebuah visi. Tetapi, hari ini sesungguhnya nyata, menjadikan kemarin sebagai mimpi kebahagiaan, dan setiap hari esok adalah visi harapan. -

Sudargo Gautama and the Development of Indonesian Public Order: a Study on the Application of Public Order Doctrine in a Pluralistic Legal System

Sudargo Gautama and the Development of Indonesian Public Order: A Study on the Application of Public Order Doctrine in a Pluralistic Legal System Yu Un Oppusunggu A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2015 Reading Committee: John O. Haley, Chair Michael E. Townsend Beth E. Rivin Program Authorized to Offer Degree School of Law © Copyright 2015 Yu Un Oppusunggu ii University of Washington Abstract Sudargo Gautama and the Development of Indonesian Public Order: A Study on the Application of Public Order Doctrine in a Pluralistic Legal System Yu Un Oppusunggu Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor John O. Haley School of Law A sweeping proviso that protects basic or fundamental interests of a legal system is known in various names – ordre public, public policy, public order, government’s interest or Vorbehaltklausel. This study focuses on the concept of Indonesian public order in private international law. It argues that Indonesia has extraordinary layers of pluralism with respect to its people, statehood and law. Indonesian history is filled with the pursuit of nationhood while protecting diversity. The legal system has been the unifying instrument for the nation. However the selected cases on public order show that the legal system still lacks in coherence. Indonesian courts have treated public order argument inconsistently. A prima facie observation may find Indonesian public order unintelligible, and the courts have gained notoriety for it. This study proposes a different perspective. It sees public order in light of Indonesia’s legal pluralism and the stages of legal development. -

Digital Repository Universitas Jember Digital Repository Universitas Jember 106

DigitalDigital RepositoryRepository UniversitasUniversitas JemberJember SKRIPSI PERAN AKBAR TANDJUNG DALAM MENYELAMATKAN PARTAI GOLKAR PADA MASA KRISIS POLITIK PADA TAHUN 1998-1999 Oleh Mega Ayu Lestari NIM 090110301022 JURUSAN ILMU SEJARAH FAKULTAS SASTRA UNIVERSITAS JEMBER 2016 DigitalDigital RepositoryRepository UniversitasUniversitas JemberJember PERAN AKBAR TANDJUNG DALAM MENYELAMATKAN PARTAI GOLKAR PADA MASA KRISIS POLITIK PADA TAHUN 1998-1999 SKRIPSI Skripsi diajukan guna melengkapi tugas akhir dan memenuhi salah satu syarat untuk menyelesaikan studi pada Jurusan Sejarah (S1) dan mencapai gelar sarjana sastra Oleh Mega Ayu Lestari NIM 090110301022 JURUSAN ILMU SEJARAH FAKULTAS SASTRA UNIVERSITAS JEMBER 2016 DigitalDigital RepositoryRepository UniversitasUniversitas JemberJember PERNYATAAN Saya yang bertanda tangan dibawah ini : Nama : Mega Ayu Lestari NIM : 090110301022 Menyatakan dengan sesungguhnya bahwa karya ilmiah yang berjudul:Peran Akbar Tandjung Dalam Menyelamatkan Partai Golkar Pada Masa Krisis Politik Pada Tahun 1998-1999”adalah benar-benar hasil karya ilmiah sendiri, kecuali jika dalam pengutipan substansi disebutkan sumbernya, dan belum pernah diajukan pada institusi manapun, serta bukan karya jiplakan. Saya bertanggung jawab atas keabsahan dan kebenaran isinya sesuai dengan sikap ilmiah yang harus dijunjung tinggi. Demikian pernyataan ini saya buat dengan sebenarnya, tanpa adanya tekanan dan paksaan dari pihak manapun serta bersedia mendapat sanksi akademik jika ternyata dikemudian hari pernyataan ini tidak benar. Jember,14Maret -

The Cultural Traffic of Classic Indonesian Exploitation Cinema

The Cultural Traffic of Classic Indonesian Exploitation Cinema Ekky Imanjaya Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of East Anglia School of Art, Media and American Studies December 2016 © This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with the author and that use of any information derived there from must be in accordance with current UK Copyright Law. In addition, any quotation or extract must include full attribution. 1 Abstract Classic Indonesian exploitation films (originally produced, distributed, and exhibited in the New Order’s Indonesia from 1979 to 1995) are commonly negligible in both national and transnational cinema contexts, in the discourses of film criticism, journalism, and studies. Nonetheless, in the 2000s, there has been a global interest in re-circulating and consuming this kind of films. The films are internationally considered as “cult movies” and celebrated by global fans. This thesis will focus on the cultural traffic of the films, from late 1970s to early 2010s, from Indonesia to other countries. By analyzing the global flows of the films I will argue that despite the marginal status of the films, classic Indonesian exploitation films become the center of a taste battle among a variety of interest groups and agencies. The process will include challenging the official history of Indonesian cinema by investigating the framework of cultural traffic as well as politics of taste, and highlighting the significance of exploitation and B-films, paving the way into some findings that recommend accommodating the movies in serious discourses on cinema, nationally and globally. -

Nabbs-Keller 2014 02Thesis.Pdf

The Impact of Democratisation on Indonesia's Foreign Policy Author Nabbs-Keller, Greta Published 2014 Thesis Type Thesis (PhD Doctorate) School Griffith Business School DOI https://doi.org/10.25904/1912/2823 Copyright Statement The author owns the copyright in this thesis, unless stated otherwise. Downloaded from http://hdl.handle.net/10072/366662 Griffith Research Online https://research-repository.griffith.edu.au GRIFFITH BUSINESS SCHOOL Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY By GRETA NABBS-KELLER October 2013 The Impact of Democratisation on Indonesia's Foreign Policy Greta Nabbs-Keller B.A., Dip.Ed., M.A. School of Government and International Relations Griffith Business School Griffith University This thesis is submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. October 2013 Abstract How democratisation affects a state's foreign policy is a relatively neglected problem in International Relations. In Indonesia's case, there is a limited, but growing, body of literature examining the country's foreign policy in the post- authoritarian context. Yet this scholarship has tended to focus on the role of Indonesia's legislature and civil society organisations as newly-empowered foreign policy actors. Scholars of Southeast Asian politics, meanwhile, have concentrated on the effects of Indonesia's democratisation on regional integration and, in particular, on ASEAN cohesion and its traditional sovereignty-based norms. For the most part, the literature has completely ignored the effects of democratisation on Indonesia's foreign ministry – the principal institutional actor responsible for foreign policy formulation and conduct of Indonesia's diplomacy. Moreover, the effect of Indonesia's democratic transition on key bilateral relationships has received sparse treatment in the literature. -

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Ripples, Echoes, and Reverberations: 1965 and Now in Indonesia Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5fv121wm Author Stroud, Martha Publication Date 2015 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Ripples, Echoes, and Reverberations: 1965 and Now in Indonesia by Martha Stroud A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Joint Doctor of Philosophy with University of California, San Francisco in Medical Anthropology in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Nancy Scheper-Hughes, Chair Professor Laura Nader Professor Sharon Kaufman Professor Jeffrey A. Hadler Spring 2015 “Ripples, Echoes, and Reverberations: 1965 and Now in Indonesia” © 2015 Martha Stroud 1 Abstract Ripples, Echoes, and Reverberations: 1965 and Now in Indonesia by Martha Stroud Joint Doctor of Philosophy with University of California, San Francisco in Medical Anthropology University of California, Berkeley Professor Nancy Scheper-Hughes, Chair In Indonesia, during six months in 1965-1966, between half a million and a million people were killed during a purge of suspected Communist Party members after a purported failed coup d’état blamed on the Communist Party. Hundreds of thousands of Indonesians were imprisoned without trial, many for more than a decade. The regime that orchestrated the mass killings and detentions remained in power for over 30 years, suppressing public discussion of these events. It was not until 1998 that Indonesians were finally “free” to discuss this tragic chapter of Indonesian history. In this dissertation, I investigate how Indonesians perceive and describe the relationship between the past and the present when it comes to the events of 1965-1966 and their aftermath.