Gujarat Earthquake Recovery Program Assessment Report A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reconstruction & Renewal of Bhuj City

Reconstruction & Renewal of Bhuj City The Gujarat Earthquake Experience - Converting Adversity into an Opportunity a presentation by: Rajesh Kishore, CEO, Gujarat State Disaster Management Authority Gujarat, India Bhuj City – Key Facts A 500 year old traditional unplanned city Headquarters of Kutch district – seat of district government Population of about 1,50,000 Strong Livelihood base - handicrafts and handloom work Disaster Profile ¾ Earthquakes – Active seismic faults surround the city ¾ Drought – every alternate year 2370 dead, 3187 injured One of the 6402 houses destroyed worst affected cities 6933 houses damaged in the earthquake of 2001 + markets, offices, civic Infrastructure etc 2 Vulnerability of Urban Areas – Pre-Earthquake ¾ Traditionally laid out city - Historical, old buildings with poor quality of construction ¾ Poor accessibility in city areas for immediate evacuation, rescue and relief operations ¾ Inadequate public sensitivity for disaster preparedness ¾ Absence of key institutions for disaster preparedness urban planning, emergency response, disaster mitigation ¾ Inadequate and inappropriate equipment/ facilities/ manpower for search and rescue capabilities 3 URBAN RE-ENGINEERING GUIDING PRINCIPLES ¾ RECONSTRUCTION AS A DEVELOPMENT OPPORTUNITY - Provide a Better Living Environment ¾ DEVELOPING MULTI-HAZARD RESISTANT CAPABILITY - Improved Technologies and Materials e.g; ¾ ENSURING PUBLIC PARTICIPATION - In Planning and Implementation ¾ PLANNING URBAN RE-ENGINEERING - On Scientific and Rational Criteria ¾ RESTORING -

The Reconstruction of Bhuj Case Study: Integration of Disaster

The Reconstruction of Bhuj Case Study: Integration of Disaster Mitigation into Planning and Financing Urban Infrastructure after an Earthquake B.R. Balachandran Introduction to EPC and its Involvement in Bhuj The Environmental Planning Collaborative (EPC), established in 1996, is a not for profit, private, professional planning and development management company. The company provides professional consultancy services primarily to urban local bodies including municipal corporations and urban development authorities. EPC also works with a variety of other agencies involved in urban development such as state government departments, international funding and lending agencies, special purpose vehicles for urban development and non-government/autonomous organizations. Most projects are undertaken in a collaborative and participatory manner with significant involvement from the client, major stakeholders and other related agencies. EPC’s work is primarily of four types: (1) urban and regional development planning, (2) environmental and policy planning, (3) development management and (4) research and development. Immediately after the earthquake, EPC deputed its personnel in Bhuj to study the situation and initiate public consultations. This evolved into a USAID funded project entitled “Initiative for Planned and Participatory Reconstruction in Kutch” (IPPR) in collaboration with The Communities Group International (TCGI). The IPPR consisted of experiments in participatory planning at the regional level and in urban and rural communities. This was followed by a United States-Asia Environmental Partnership (USAEP)-funded project, “Atlas for Post-Disaster Reconstruction” under which EPC in collaboration with the Planning and The Reconstruction of Bhuj Development Company (PADCO) prepared maps of the four towns showing plot level information on intensity of damage, land use and number of floors. -

Surendranagar Index

SURENDRANAGAR INDEX 1 Surendranagar: A Snapshot 2 Economy and Industry Profile 3 Industrial Locations / Infrastructure 4 StIfttSupport Infrastructure 5 Social Infrastructure 6 Tourism 7 IttOtitiInvestment Opportunities 8 Annexure 2 1 Surendranagar: A Snapshot 3 Introduction: Surendranagar Map1: District Map of Surendranagar with Surendranagar district is located in the central region of Talukas Gujarat, in the Saurashtra peninsula The district comprises of 10 talukas. Developed amongst them are Surendranagar, Wadhwan, Limbdi, Chotila, Dhrangadhra, and Lakhtar Surendranagar is one of the largest producers of “Shankar” Cotton in the world and, is also the home to the first cotton Patdi trading exchange in India Haaadlwad Dhangadhra Focus idindus try sectors are ttiltextiles, chilhemicals, and Lakhtar ceramics Surendranagar Muli Wadhawan Limbdi Some of the major tourist destinations in the district are Sayla Chuda Tarnetar Mela, Chotila Hills and Ranakdevi Temple Chotila District Headquarter Talukas 4 Fact File 69.45º to 72.15º East ((gLongitude) Geographical location 22.00º to 23.04º North (Latitude) 45.6º Centigrade (Maximum) Temperature 7.8º Centigg(rade (Minimum) Average Rainfall 760 mm Bhogavo, Sukhbhadar, Brahmani, Kankavati, Vansal, Rupen, Falku, Rivers Vrajbhama, Umai, and Chandrabhaga Area 10,489 sq. km District Headquarter Surendranagar Talukas 10 Population 15,15,147 (As per 2001 Census) Population Density 144 Persons per sq. Km Sex Ratio 924 Females per 1000 Males Literacy Rate 61.6% Languages Gujarati, Hindi, and English -

08Kutch Kashmireq.Pdf

Key Idea From Kutch to Kashmir: Lessons for Use Since, October 11, 2005 early hours AIDMI team is in Kashmir assessing losses and needs. The biggest gap found is of understanding earthquake. Five key gaps are addressed here. nderstanding India's vulnerability: Using earthquake science to enhance Udisaster preparedness Every year, thousands flock to Kashmir, in India and Pakistan to marvel at her spectacular scenery and majestic mountain ranges. However, the reality of our location and mountainous surroundings is an inherent threat of devastating earthquakes. In addition to accepting earthquakes as a South Asian reality, we as humanitarian respondents as well as risk reduction specialists must now look to science to enhance disaster risk mitigation and preparedness.The humanitarian communalities know little about what scientific communities have discovered and what could be used to mitigate risk of earthquakes. Similarly, scientific communities need to know how to put scientific knowledge in mitigation perspective from the point of view of non-scientific communities. How do we bridge this gap? We at AIDMI acknowledged this gap, and from the overlapping questions, we selected four key areas relevant to Kashmir and South Asia and discussed them in this issue. Editorial Advisors: How do we use scientific knowledge on earthquakes? Dr. Ian Davis Certain regions of South Asia are more vulnerable to earthquakes than others. Kashmir Cranfield University, UK ranks high on this list. Fortunately, geologists know which regions are more vulnerable Kala Peiris De Costa and why. When this information is disseminated to NGOs, relief agencies and Siyath Foundation, Sri Lanka governments, they can quickly understand where investments, attention and disaster Khurshid Alam preparedness measures should be focussed. -

Kutch District Disaster Management Plan 2017-18

Kutch District Disaster Management Plan 2017-18 District: Kutch Gujarat State Disaster Management Authority Collector Office Disaster Management Cell Kutch – Bhuj Kutch District Disaster Management Plan 2016-17 Name of District : KUTCH Name of Collector : ……………………IAS Date of Update plan : June- 2017 Signature of District Collector : _______________________ INDEX Sr. No. Detail Page No. 1 Chapter-1 Introduction 1 1.01 Introduction 1 1.02 What is Disaster 1 1.03 Aims & Objective of plan 2 1.04 Scope of the plan 2 1.05 Evolution of the plan 3 1.06 Authority and Responsibility 3 1.07 Role and responsibility 5 1.08 Approach to Disaster Management 6 1.09 Warning, Relief and Recovery 6 1.10 Mitigation, Prevention and Preparedness 6 1.11 Finance 7 1.12 Disaster Risk Management Cycle 8 1.13 District Profile 9 1.14 Area and Administration 9 1.15 Climate 10 1.16 River and Dam 11 1.17 Port and fisheries 11 1.18 Salt work 11 1.19 Live stock 11 1.20 Industries 11 1.21 Road and Railway 11 1.22 Health and Education 12 2 Chapter-2 Hazard Vulnerability and Risk Assessment 13 2.01 Kutch District past Disaster 13 2.02 Hazard Vulnerability and Risk Assessment of Kutch district 14 2.03 Interim Guidance and Risk & Vulnerability Ranking Analysis 15 2.04 Assign the Probability Rating 15 2.05 Assign the Impact Rating 16 2.06 Assign the Vulnerability 16 2.07 Ranking Methodology of HRVA 17 2.08 Identify Areas with Highest Vulnerability 18 2.09 Outcome 18 2.10 Hazard Analysis 18 2.11 Earthquake 19 2.12 Flood 19 2.13 Cyclone 20 2.14 Chemical Disaster 20 2.15 Tsunami 20 2.16 Epidemics 21 2.17 Drought 21 2.18 Fire 21 Sr. -

Gujarat Cotton Crop Estimate 2019 - 2020

GUJARAT COTTON CROP ESTIMATE 2019 - 2020 GUJARAT - COTTON AREA PRODUCTION YIELD 2018 - 2019 2019-2020 Area in Yield per Yield Crop in 170 Area in lakh Crop in 170 Kgs Zone lakh hectare in Kg/Ha Kgs Bales hectare Bales hectare kgs Kutch 0.563 825.00 2,73,221 0.605 1008.21 3,58,804 Saurashtra 19.298 447.88 50,84,224 18.890 703.55 78,17,700 North Gujarat 3.768 575.84 12,76,340 3.538 429.20 8,93,249 Main Line 3.492 749.92 15,40,429 3.651 756.43 16,24,549 Total 27.121 512.38 81,74,214 26.684 681.32 1,06,94,302 Note: Average GOT (Lint outturn) is taken as 34% Changes from Previous Year ZONE Area Yield Crop Lakh Hectare % Kgs/Ha % 170 kg Bales % Kutch 0.042 7.46% 183.21 22.21% 85,583 31.32% Saurashtra -0.408 -2.11% 255.67 57.08% 27,33,476 53.76% North Gujarat -0.23 -6.10% -146.64 -25.47% -3,83,091 -30.01% Main Line 0.159 4.55% 6.51 0.87% 84,120 5.46% Total -0.437 -1.61% 168.94 32.97% 25,20,088 30.83% Gujarat cotton crop yield is expected to rise by 32.97% and crop is expected to increase by 30.83% Inspite of excess and untimely rains at many places,Gujarat is poised to produce a very large cotton crop SAURASHTRA Area in Yield Crop in District Hectare Kapas 170 Kgs Bales Lint Kg/Ha Maund/Bigha Surendranagar 3,55,100 546.312 13.00 11,41,149 Rajkot 2,64,400 714.408 17.00 11,11,115 Jamnagar 1,66,500 756.432 18.00 7,40,858 Porbandar 9,400 756.432 18.00 41,826 Junagadh 74,900 756.432 18.00 3,33,275 Amreli 4,02,900 756.432 18.00 17,92,744 Bhavnagar 2,37,800 756.432 18.00 10,58,115 Morbi 1,86,200 630.360 15.00 6,90,430 Botad 1,63,900 798.456 19.00 7,69,806 Gir Somnath 17,100 924.528 22.00 92,997 Devbhumi Dwarka 10,800 714.408 17.00 45,386 TOTAL 18,89,000 703.552 16.74 78,17,700 1 Bigha = 16 Guntha, 1 Hectare= 6.18 Bigha, 1 Maund= 20 Kg Saurashtra sowing area reduced by 2.11%, estimated yield increase 57.08%, estimated Crop increase by 53.76%. -

Nesting in Paradise Bird Watching in Gujarat

Nesting in Paradise Bird Watching in Gujarat Tourism Corporation of Gujarat Limited Toll Free : 1800 200 5080 | www.gujarattourism.com Designed by Sobhagya Why is Gujarat such a haven for beautiful and rare birds? The secret is not hard to find when you look at the unrivalled diversity of eco- Merry systems the State possesses. There are the moist forested hills of the Dang District to the salt-encrusted plains of Kutch district. Deciduous forests like Gir National Park, and the vast grasslands of Kutch and Migration Bhavnagar districts, scrub-jungles, river-systems like the Narmada, Mahi, Sabarmati and Tapti, and a multitude of lakes and other wetlands. Not to mention a long coastline with two gulfs, many estuaries, beaches, mangrove forests, and offshore islands fringed by coral reefs. These dissimilar but bird-friendly ecosystems beckon both birds and bird watchers in abundance to Gujarat. Along with indigenous species, birds from as far away as Northern Europe migrate to Gujarat every year and make the wetlands and other suitable places their breeding ground. No wonder bird watchers of all kinds benefit from their visit to Gujarat's superb bird sanctuaries. Chhari Dhand Chhari Dhand Bhuj Chhari Dhand Conservation Reserve: The only Conservation Reserve in Gujarat, this wetland is known for variety of water birds Are you looking for some unique bird watching location? Come to Chhari Dhand wetland in Kutch District. This virgin wetland has a hill as its backdrop, making the setting soothingly picturesque. Thankfully, there is no hustle and bustle of tourists as only keen bird watchers and nature lovers come to Chhari Dhand. -

Observations from the Bhuj Earthquake of January 26, 2001

Observations From the Bhuj Earthquake of January 26, 2001 The devastating earthquake that struck the Kutch area of Gujarat, India on January 26, 2001, India’s Republic Day, was the most severe natural disaster to afflict India since her independence in 1947. The devastation was major in terms of lives lost, injuries suffered, people rendered homeless, as well as economics. The author visited the affected areas between February 12 and 16, 2001, as a member of a reconnaissance team that was organized by the Mid-America Earthquake Center based at the University of Illinois at Urbana- Champaign and funded by the National Science Foundation. This report is based partly on his first-hand observations from that visit and partly on information gathered from several sources, including other visiting teams, news reports and technical literature. The author touches upon seismological/geotechnical aspects of the earthquake and discusses the performance of engineered buildings. Bridges, non- engineered buildings and other structures are excluded from the scope. S. K. Ghosh, Ph.D. Precast concrete construction, including non-building uses of precast President concrete, is discussed. In concluding the article, the building code S. K. Ghosh Associates, Inc. situation in India is briefly commented upon. Northbrook, Illinois he Bhuj earthquake of January 26, 2001 struck at 8:46 image of the geology and earthquake history of the New a.m. Indian Standard time and had a Richter magni- Madrid earthquakes of 1811 and 1812, the largest earth- Ttude of 7.7 (United States Geological Survey, revised quakes to occur in the U.S. continental 48 states, even from an initial estimate of 7.8). -

Final Report

No. JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY (JICA) GOVERNMENT OF GUJARAT THE RECONSTRUCTION SUPPORT FOR THE GUJARAT-EARTHQUAKE DISASTER IN THE DEVASTATED AREAS IN INDIA FINAL REPORT OCTOBER, 2002 YAMASHITA SEKKEI INC. NIHON SEKKEI, INC. S S F J R 02-161 Currency Equivalents Exchange rate effective as of June, 2001 Currency Unit = Rupee(Rs.) $ 1.00 = Rs.46.0 1Rs.=2.66 Japanese Yen,1 Crore = 10.000.000,1 Lakh = 100.000 Preface In response to a request from the Government of India, the Government of Japan decided to implement a project on the Reconstruction Support for the Gujarat-Earthquake Disaster in the Devastated Areas in India and entrusted the project to the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA). JICA selected and dispatched a project team headed by Mr. Toshio Ito of Yamashita Sekkei Inc., the representing company of a consortium consists of Yamashita Sekkei Inc. and Nihon Sekkei, Inc., from June 6th, 2001 to May 29th, 2002 and from August 4th to August 18th, 2002. In addition, JICA selected an advisor, Mr. Osamu Yamada of the Institute of International Cooperation who examined the project from specialist and technical points of view. The team held discussions with the officials concerned of the Government of India and the Government of Gujarat and conducted a field survey and implemented quick reconstruction support project for the primary educational and healthcare sectors. After the commencement of the quick reconstruction support project the team conducted further studies and prepared this final report. I hope that this report will contribute to the promotion of the project and to the enhancement of friendly relationships between our two countries. -

List of Forest Divisions with Code

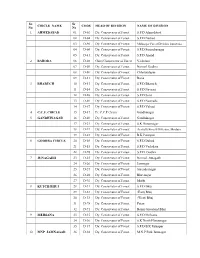

Sr. Sr CIRCLE NAME CODE HEAD OF DIVISION NAME OF DIVISION No. No 1 AHMEDABAD 01 D-02 Dy. Conservator of Forest S.F.D Ahmedabad 02 D-04 Dy. Conservator of Forest S.F.D Nadiad 03 D-96 Dy. Conservator of Forest Mahisagar Forest Division, Lunavada. 04 D-06 Dy. Conservator of Forest S.F.D Surendranagar 05 D-81 Dy. Conservator of Forest S.F.D Anand 2 BARODA 06 D-08 Chief Conservator of Forest Vadodara 07 D-09 Dy. Conservator of Forest Normal Godhra 08 D-10 Dy. Conservator of Forest Chhotaudepur 09 D-11 Dy. Conservator of Forest Baria 3 BHARUCH 10 D-13 Dy. Conservator of Forest S.F.D Bharuch 11 D-14 Dy. Conservator of Forest S.F.D Navsari 12 D-16 Dy. Conservator of Forest S.F.D Surat 13 D-80 Dy. Conservator of Forest S.F.D Narmada 14 D-87 Dy. Conservator of Forest S.F.D Valsad 4 C.C.F. CIRCLE 15 D-17 Pr. C.C.F (A/cs) Gandhinagar 5 GANDHINAGAR 16 D-20 Dy. Conservator of Forest Gandhinagar 17 D-21 Dy. Conservator of Forest S.K Himatnagar 18 D-97 Dy. Conservator of Forest Aravalli Forest Division, Modasa 19 D-23 Dy. Conservator of Forest B.K Palanpur 6 GODHRA CIRCLE 20 D-03 Dy. Conservator of Forest S.F.D Dahod 21 D-15 Dy. Conservator of Forest S.F.D Vadodara 22 D-98 Dy. Conservator of Forest S.F.D. Godhra 7 JUNAGADH 23 D-25 Dy. -

District Development Officer

District Development Officer District District Development Officer Phone No. Email Ahmedabad Shri V. A. Vaghela (O) 079 - 25506487 District Development Officer, (F) 079 - 25511359 District Panchayat, Ahmedabad. Amreli Shri Nirgude Yogesh Babanro (O) 02792 - 222313 District Development Officer, (F) 02792 - 222378 District Panchayat, Amreli. Anand Shri Amit Prakash Yadav (O) 02692 - 241110 District Development Officer, (F) 02692 - 243895 District Panchayat, Anand. Kheda Shri Sudhir B. Patel (O) 0268 - 257262 ( Nadiad) District Development Officer, (F) 0268 - 257851 District Panchayat, Kheda. Banaskantha Shri Amit Arora (O) 02742 - 254060 (Palanpur) District Development Officer, (F) 02742 - 252063 District Panchayat, Banaskatha. Bharuch Ms. Agre Kshipra (O) 02642 - 240603 Suryakantarao (F) 02642 - 240951 District Development Officer, District Panchayat, Bharuch. Bhavnagar Shri Oak Aayush Sanjeev (O) 0278 - 2426810 District Development Officer, (F) 0278 - 2430295 District Panchayat, Bhavnagar. Dahod Shri Sujal Mayatra (O) 02673 - 247066 District Development Officer, (F) 02673 - 247438 District Panchayat, Dahod. Dangs Shri H. K. Vadhvaniya (O) 02631 - 220254 (Ahwa) District Development Officer, (F) 02631 - 220444 District Panchayat, Dangs. Gandhinagar Shri D. P. Desai (O) 079 - 23222618 District Development Officer, (F) 079 - 23223266 District Panchayat, Gandhinagar. Jamnagar Shri M. A. Pandya District Development Officer, (O) 0288 - 2553901 District Panchayat, 0288 - 2553901 Jamnagar. (F) 0288 - 2552394 Junagadh Shri Ajay Prakash (O) 0285 - 2651001 District Development Officer, (F) 0285 - 2651222 District Panchayat, Junagadh. Kutch - Bhuj Shri C. J. Patel (O) 02832 - 250080 District Development Officer, (F) 02832 - 250355 District Panchayat, Kachchh. Mehsana Shri J. B. Patel (O) 02762 - 222301 District Development Officer, (F) 02762 - 221447 District Panchayat, Mehsana. Navsari Shri Tushar D. Sumera (O) 02637 - 244299 District Development Officer, (F) 02637 - 230475 District Panchayat, Navsari. -

195 Written Answers 18 MARCH, 1997 to Questions 196 Atrocities On

195 Written Answers 18 MARCH, 1997 to Questions 196 Atrocities on Tribals (a) the locations and the capacity of FCI godowns situated in Gujarat; .S6b6. SHRI K. PRADHANI ; Will the Minister of WELFARE be pleased to state: (b) the number of godowns hired by FCI; (c) whether the Government have any plan to open up (a) whether the attention of the Government has been new Divisional offices/godowns in Gujarat in the near future; drawn to the news item captioned ‘Tribal Couple Sthpped and by Villages" appearing in ‘Statesman’. (New Delhi Edition) dated February 15, 1997; (d) if so, the locations and the storage capacity thereof? (b) so. the details thereof; and THE MINISTER OF FOOD AND MINISTER OF CIVIL SUPPLIES, CONSUMER AFFAIRS AND PUBLIC (Cl the action taken against the culprits? DISTRIBUTION (SHRI DEVENDRA PRASAD YADAV) : (a) Statements -I and II containing details of Food Corporation THE MINISTER OF WELFARE (SHRI BALWANT of India godowns (owned & hired/covered & CAP) in Gujarat SINGH RAMOOWALIA) ; (a) to (c) Yes, Sir. The information as on 1.2.1997 are attached. !S being collected and will be laid on the Table of the House. (b) The total number of godowns hired by FCI in Gujarat FCI Godowns in Gujarat as on 1.2.1997 is 25. (c) No, Sir. 3657 SHRI RAJENDRASINH RANA ; Will the Minister of FOOD be pleased to state; (d) Does not arise. StatemenN The Covered Storage Capacity (Owned & Hired) Available with the Food Corporation of India in Gujarat State as on 1.2.1997 (Fig. in ‘000’ Tonnes) Name ot the Name of the Name of the Covered FCI Distt Revenue Distt.