19 Eusebiusbuitensingel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Seasons at Amersham & Chiltern RFC

seasons at Amersham & Chiltern RFC A HISTORY OF THE CLUB 1924-2004 seasons at Amersham & Chiltern RFC WRITTEN AND RESEARCHED BY ROGER COOK © Roger Cook 2004. Interviews, named articles and illustrations are copyright to the several contributors. 1 Eighty seasons at Amersham & Chiltern RFC Dedication Author’s introduction and acknowledgments n 1992, on a Saturday evening at the Chiltern clubhouse bar, his condensed history of Chiltern as in many previous seasons past Griff Griffiths was holding Rugby Football Club is dedicated to Icourt. He would have then been seventy seven years of age. “Someone in the club has to write down the club's history and I Arthur Gerald ‘Griff’ Griffiths who T am too old”. Several people had started, John Carpenter and Colin passed away in 1995. Maloney were names that Griff mentioned. From somewhere Griff fortunately had the opportunity to within, I suddenly heard myself volunteering for yet another job at the club. Roger Cook edit the initial collected stories and I feel Of the many varied tasks I have carried out around the club over the past thirty years, confident that his fear of losing the several have been very rewarding. But the satisfaction gained over the last twelve years spent connections with bygone days of the club in researching the first years of the club's history has surpassed all others by far. to which he was so devoted are My first box of information was passed down from John Carpenter. John when Chairman of the club in the 1980s had put together a brief history for a 65th anniversary appeal. -

Steve's Story

Steve’s Story (1943-1945) Private Stephen George Morgan No. 14436780 Colour Sergeant Rouse. for a few days and was posted to In early February 1944 we went the Second Parachute Battalion to Hardwick Hall, near Chesterfeld and put in the Medium Machine for two weeks physical training, Gun (MMG) Platoon as I had had which included clif climbing in MMG experience with the Home an old stone quarry. At the end of Guard. Te Second Parachute February I was sent to Ringway Battalion were stationed at Stoke Airport, which is now Manchester Rochford, near Saltby aerodrome City airport, and lived for two and I arrived there on the 5th May, weeks in Nissan huts. For the frst 1944 and although nobody knew week we were in a hanger practising we were due to arrive, we were drops. For the second week we fed but had to sleep on the tennis went to Tatton Park and did two courts! It was about this time that jumps from a static balloon, fve all of the new reinforcements were jumps from a Whitley bomber in driven to a nearby airfeld and daylight (my course number was taken up in a Dakota to do a jump 106) and one jump at night from and this was the frst time that I uring World War II the the balloon and that was it! We had been in a Dakota. call up age was 17 years were given our red berets and a pair While we were there we were 9 months. As I was not of wings to sew on our right sleeve joined by Major Tate, who had Dquite that old I volunteered to join and we had fnished our training! I previously served in North Africa the Army and went for a medical remember going into the Ringway and although we were trained and “took the King’s shilling”. -

A Tribute to the Life of Jack Grayburn. Preface

A Tribute to The Life of Jack Grayburn. Preface. To be President of our great rugby club is an honour and a privilege, especially so when one considers the many illustrious members in our 90 odd years of history. We live now in very different times. The first members of Chiltern RFC will have experienced, some at first hand the almost unbearably tragic events of the World War 1. As the club grew in the 1930s the shadow of war once again fell over Europe and men such as Jack Grayburn knew what could befall them should another conflict unfold. It is difficult for us now to comprehend the sacrifices that war dictates, the destruction of families, communities, a way of life. But those Chiltern rugby players in the late 1930s must have known what might be expected of them, and must have trusted that they would rise to the challenge, and must have known that some of them would not return. Our honours board at the club has 22 names on it, a club with perhaps 60 playing members in 1939. This ratio speaks for itself, a number that is shocking and humbling; and however many times this refrain is repeated it is no less true: they died so that we might have a future, a future to enjoy the manifold benefits of a good life in a free society. And surely each one of those Chiltern players who went to war and did not return would rejoice that our club continues and is in fine shape, upholding the same values, embodying all that is best in sport and comradeship. -

2019 Easy Company Sept3 Airforce.Indd

IN COLLABORATION WITH THE NATIONAL WWII MUSEUM TRAVEL Featuring the Two-Night Optional Pre-Tour Extension Churchill’s London EASY COMPANY: ENGLAND TO THE EAGLE’S NEST Based on the best-selling book, Band of Brothers by Museum founder Stephen E. Ambrose and featuring original cast-members from the award-winning HBO miniseries. September 4 – 16, 2019 Save $1,000 per couple when booked by April 26, 2019 FEATURED GUEST Dear Alumni and Friends, For three decades, Stephen Ambrose and Gordon H. “Nick” Mueller, President and CEO Emeritus of The National WWII Museum, were colleagues in the Department of History at the University of New Orleans – and best friends. During those years they undertook many adventures, including the first overseas tour Ambrose led – a 1980 journey from the Normandy D-Day beaches to the Rhine River. They fell in love with helping others experience this epic story and wanted to go back as often as they could. Ambrose and Mueller ran tours almost every other year for some 20 years, including one in 1994 commemorating the 50th anniversary of D-Day. It was during those years, as Mueller served as a Dean and Vice Chancellor at UNO, that he and Ambrose established the Eisenhower Center for American Studies, which facilitated the collection of more than 600 oral histories from D-Day veterans. This included interviews and other research materials provided by surviving members of the famed Easy Company. Travel in the company an original cast Beginning in 1990, Normandy tours were planned around the wartime route member from the award-winning HBO miniseries, of the “Band of Brothers,” from the drop zones around Sainte-Mère-Église all the way to Hitler’s Eagle’s Nest in the Bavarian Alps. -

Where Eagles Dare Exclusive Rules

Exclusive Rules & Scenarios Where Eagle’s Dare Table of Contents S5.0 German Special Rules ....................................20 S5.1 German Reorganization ....................................20 1.0 Night and Weather ...........................................7 S5.2 The Eindhoven Air Raid ....................................20 1.1 Night ..................................................................7 S5.3 Divisional Trucks ................................................20 1.2 Fog ...................................................................7 S5.4 German Flak Units ............................................21 2.0 Terrain ..............................................................7 S5.5 KG Huber ..........................................................21 2.1 Clear .................................................................7 S6.0 Allied Special Rules ........................................21 2.2 Polder ................................................................7 S6.1 Allied Supply .....................................................21 2.3 Orchard .............................................................8 S6.2 Allied Dispatch Point Discounts .........................21 2.4 Woods ...............................................................8 S6.3 Divisional Jeeps ................................................21 2.5 Roads ................................................................8 S6.4 Night Turn Restrictions on Guards Armored 2.6 Railroads ...........................................................8 -

The Original Band of Brothers Tour

Stephen Ambrose Historical Tours presents The Original Band Of BrOThers TOur Walk in The Footsteps of The Men of Easy Company 15-Day Tour: May 1TO – ur15 / July 17 – 31 / September 4 – 18 May T 2015 13-Day Tour: MaysOld 2 –Ou 15 / July 18 – 31 / September 5 – 18 Day 1 Arrival in Atlanta The tour begins in Atlanta with an informal Welcome Reception where participants will have an opportunity to get acquainted with each other and meet the historians and tour staff. A brief overview of the legacy of Easy Company will set the stage for the days ahead. Day 2 Toccoa: Birthplace of the 506th Ask any of the original members of Easy Company what made the unit so special and they will answer: “Toccoa.” This training ground in the north Georgia woods was where the bonding process of the 506th began. As it did for so many of the men of Easy Company, our tour of Toccoa will begin at the train station where recruits for the 506th first arrived. The station also houses the Stephens County Historical Immortalized by the Stephen Ambrose best-seller, “Band of Society, the 506th Museum and the unique collection of Brothers,” and brought to millions more in the epic Steven artifacts and memorabilia from Camp Toccoa. Following Spielberg/Tom Hanks HBO miniseries of the same name, the men of Easy Company were on an extraordinary journey lunch, we travel to the site of the Camp and then during WWII. From D-Day to V-E Day, the paratroopers of E proceed up Mount Currahee, the 1,000 foot mountain Company, 506th Parachute Infantry Regiment participated in the men of the 506th ran daily for training. -

07 St. Elisabeths Gasthuis

07 St. Elisabeths Gasthuis Previous history Sunday 17 September 1944 Sunday 24 September 1944 After the Battle of Arnhem Previous history The hospitals in Arnhem in 1944 Of the three Arnhem hospitals – the Diaconessenhuis, the Gemeente- ziekenhuis and St. Elisabeths Gasthuis – the last-mentioned was the only one to be caught up in the front line in the Battle of Arnhem. The building dates from 1893 and was the only Roman Catholic hospital in the city. The Diaconessenhuis catered for the Protestant patients and is the oldest Arnhem hospital, while the Gemeenteziekenhuis treated all patients irrespective of religious belief. This division was in accordance with the Verzuiling in Nederland (Denominationalism in the Netherlands), which was only done away with in the nineteen-sixties. In February 1995 the Arnhem hospitals were amalgamated to become the Rijnstate Ziekenhuis in Wagnerlaan. St. Elisabeths Gasthuis was then redeveloped into an apart- ment complex. The sisters’ accommodation and a number of post war extensions were demolished. Foundation St. Elisabeths Gasthuis was established in 1878 by Deacon J.H. van Basten Batenburg, who was the priest at the small St. Eusebiuskerk at Nieuwe Plein in Arnhem. The name of the hospital was taken from the German Saint Elisabeth van Thüringen (1207-1231) who, in 1227, was robbed of all her pos- sessions by the nobility of Thüringen after her husband Earl Lodewijk IV died during the Fifth Crusade. With what remained of her money Elisabeth had a hospital built in Marburg where she spent the rest of her life caring for the poor and the sick. -

OUR VISION for the FUTURE Welfare Support, Campaigning and Remembrance Call Or Order Online for Valentine’S Day Delivery

THE ROYAL BRITISH LEGIONJANUARY 2020 OUR VISION FOR THE FUTURE Welfare support, campaigning and Remembrance Call or order online for Valentine’s Day delivery Worn alone or stacked together, oth timeless and romantic, this exquisite ring trio elegantly this stunning ring set makes a conveys the depth of your love. The centre band can be dazzling impression on all who see it. worn alone or stacked between the two sparkling outer rings. As the perfect fi nishing touch, the bands are engraved with a romantic sentiment. Danbury Mint, Davis Road, Chessington KT9 1SE. ☎ Telephone orders on 0344 557 1000 Order online at www.danburymint.co.uk/h13340 The timeless beauty of radiant rubies and sparkling diamonds A Dozen Rubies Diamond Ring Set A romantic 14ct gold-plated diamond ring trio Please reserve (q’ty) ring set(s) for me as described in this offer. My satisfaction is guaranteed. that elegantly conveys the depth of your love. FOR GUARANTEED VALENTINE’S DAY DELIVERY, CALL OR ORDER ONLINE. ■ Please charge my rings to my credit/debit card. The bands are set with a dozen rubies and ten Card No. ■ Mastercard ■ Visa/Delta fi ery white diamonds, and are inscribed: “I loved you yesterday, I love you today, I love you more each passing day.” Card expiry date Signature Remarkable value at just £149 (plus £5 postage and handling), ■ I will pay by cheque or postal order. We’ll invoice you for the fi rst instalment. SEND NO MONEY NOW payable in fi ve monthly instalments of only £29.80 (plus £1 p&h). -

A Bridge Too Far?

Windels Anthony Master Geschiedenis Academiejaar 2009-2010 Universiteit Gent Faculteit Letteren en Wijsbegeerte Masterproef Operatie Market Garden en de weergave in de historische speelfilm: A Bridge Too Far? Promotor: Prof. Dr. Bruno De Wever Universiteit Gent Examencommissie Geschiedenis Academiejaar 2009-2010 Verklaring in verband met de toegankelijkheid van de scriptie Ondergetekende, ………………………………………………………………………………... afgestudeerd Master in de Geschiedenis aan Universiteit Gent in het academiejaar 2009-2010 en auteur van de scriptie met als titel: ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… ………………………………… verklaart hierbij dat zij/hij geopteerd heeft voor de hierna aangestipte mogelijkheid in verband met de consultatie van haar/zijn scriptie: o de scriptie mag steeds ter beschikking worden gesteld van elke aanvrager; o de scriptie mag enkel ter beschikking worden gesteld met uitdrukkelijke, schriftelijke goedkeuring van de auteur (maximumduur van deze beperking: 10 jaar); o de scriptie mag ter beschikking worden gesteld van een aanvrager na een wachttijd van … . jaar (maximum 10 jaar); o de scriptie mag nooit ter beschikking worden gesteld van een aanvrager (maximumduur van het verbod: 10 jaar). Elke gebruiker is te allen tijde verplicht om, wanneer van deze scriptie gebruik wordt gemaakt in het kader van wetenschappelijke en andere publicaties, een correcte en volledige bronverwijzing in de tekst op te -

Easy Company: England to the Eagle’S Nest

IN COLLABORATION WITH THE NATIONAL WWII MUSEUM EASY COMPANY: ENGLAND TO THE EAGLE’S NEST Based on the best-selling book by Museum founder Stephen E. Ambrose, and the award-winning HBO miniseries Band of Brothers JUNE 8 – 20, 2018 Featuring Band of Brothers Cast Member, James Madio SAVE $1,000 PER COUPLE* WHEN BOOKED BY NOVEMBER 10, 2017 , Dear Alumni and Friends, For three decades, Stephen Ambrose and Gordon H. “Nick” Mueller, President and CEO of The National WWII Museum, were colleagues in the Department of History at the University of New Orleans – and best friends. During those years they undertook many adventures, including the first overseas tour Ambrose led – a 1980 journey from the Normandy D-Day beaches to the Rhine River. They fell in love with helping others experience this epic story and wanted to go back as often as they could. Ambrose and Mueller ran tours almost every other year for some 20 years, including one in 1994 commemorating the 50th anniversary of D-Day. It was during those years, as Mueller served as a Dean and Vice Chancellor at UNO, that he and Ambrose established the Eisenhower Center for American Studies, which facilitated the collection of more than 600 oral histories from D-Day veterans. This included interviews and other research materials provided by FIELD MARSHAL ERWIN ROMMEL AT CHÂTEAU DE BERNAVILLE, MAY 17, 1944 surviving members of the famed Easy Company. Beginning in 1990, Normandy tours were planned around the wartime route A STORY OF BRAVERY AND HOPE of the “Band of Brothers,” from the drop zones around Sainte-Mère-Église all the way to Hitler's Eagle’s Nest in the Bavarian Alps. -

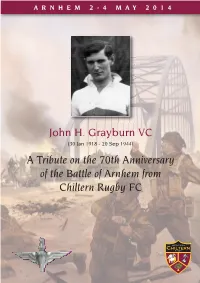

John H. Grayburn VC a Tribute on the 70Th Anniversary of the Battle of Arnhem from Chiltern Rugby FC

ARNHEM 2-4 MAY 2014 John H. Grayburn VC (30 Jan 1918 - 20 Sep 1944) A Tribute on the 70th Anniversary of the Battle of Arnhem from Chiltern Rugby FC ohn ‘ Jack ’ Hollington Grayburn was born on Manora Island, India, on J30 January 1918. However, the family soon returned to England and settled at Roughwood Farm, Chalfont St. Giles. Jack and both of his brothers were educated at Sherborne School in Dorset. Although bright, he was not academically inclined, preferring his chosen sports of rugby and boxing. From 1927, Jack played for Chiltern Rugby FC during the school holidays and continued to represent them when he left Sherborne School in 1936, playing his last First XV game on 17 April 1939. Shortly before WW2 began, Jack joined 1st (London) Cadet Force, Queen's Royal Regiment, but he was later transferred to Ox & Bucks Light Infantry. In 1942, he met and married Marcelle Chambers, a secretary at the Headquarters staff, with whom he had a son, John. Jack , once described as a “belligerent individual”, was frustrated by years of inaction on the home front and so in early 1943 he joined 2nd Battalion, 1st Parachute Brigade, commanding 2 Platoon, ‘A’ Company. Chiltern RFC 1st XV 1938-39: John H. Grayburn (standing far right) BATTLE OF ARNHEM The Battle of Arnhem was part of Operation Market Garden, an attempt by the Allies to secure a string of bridges across Netherlands. At Arnhem, the British 1st Airborne Division and Polish 1st Independent Parachute Brigade were tasked with securing bridges across the Lower Rhine, the final and furthest objectives of the operation. -

Promotion Exam Part ‘B’ Mil History 2015-16

The information given in this document is not to be communicated either directly or indirectly to the press or to any person not holding an official position in the service of the Government of India/ State Government of the Union of India. PROMOTION EXAM PART ‘B’ MIL HISTORY 2015-16 COMPILED & PUBLISHED BY THE DIRECTORATE GENERAL OF MILITARY TRAINING (MT-2) INTEGRATED HEADQUARTERS OF MoD (ARMY) INDEX MILITARY HISTORY : PART ‘B’ EXAM (2015-16) Ser Chapter Page No From To 1. Syllabus i ii PART - I : BATTLE OF ARNHEM 2. Background 02 02 3. Operation Market Garden 03 08 4. The air armada 09 17 5. The vital hours 18 26 6. Formation of Oosterbeek perimeter : 20 Sep 27 34 7. Evacuation 35 36 8. Aftermath 37 38 9. Reasons for failure 39 40 10. Lessons learnt 41 42 11. Conclusion 43 43 PART - II : OP DEADSTICK - CAPTURE OF PEGASUS BRIDGE 12. Background 45 48 13. Prep & plg for the Op 49 54 14. Airborne ops on D-day 55 58 15. Aftermath 59 59 16. Conclusion 60 60 17. Lessons learnt 61 62 PART - III : BIOGRAPHY - MAJOR JOHN HOWARD, DSO 18. The Early Years 63 65 19. Personal and Military Traits 65 69 20. Life After the War 69 69 i SYALLABI FOR PROMOTION EXAMINATION PART 'B' : MIL HISTORY (2015) (WRITTEN) Ser Subject Total Pass Time Syllabus Remarks/ No Marks Marks Allowed Recommended Study 1. Military 500 200 3 hr Aim. The aim of Military History paper is to 1. The topics for Military History History test the candidates‟ ability to draw lessons from paper would be promulgated by the prescribed campaigns and biographical DGMT (MT-2) in a block of four studies and apply these to contemporary and years.