Oral History, Collective Memory and Socio-Political Criticism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

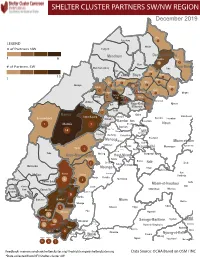

NW SW Presence Map Complete Copy

SHELTER CLUSTER PARTNERS SW/NWMap creation da tREGIONe: 06/12/2018 December 2019 Ako Furu-Awa 1 LEGEND Misaje # of Partners NW Fungom Menchum Donga-Mantung 1 6 Nkambe Nwa 3 1 Bum # of Partners SW Menchum-Valley Ndu Mayo-Banyo Wum Noni 1 Fundong Nkum 15 Boyo 1 1 Njinikom Kumbo Oku 1 Bafut 1 Belo Akwaya 1 3 1 Njikwa Bui Mbven 1 2 Mezam 2 Jakiri Mbengwi Babessi 1 Magba Bamenda Tubah 2 2 Bamenda Ndop Momo 6b 3 4 2 3 Bangourain Widikum Ngie Bamenda Bali 1 Ngo-Ketunjia Njimom Balikumbat Batibo Santa 2 Manyu Galim Upper Bayang Babadjou Malentouen Eyumodjock Wabane Koutaba Foumban Bambo7 tos Kouoptamo 1 Mamfe 7 Lebialem M ouda Noun Batcham Bafoussam Alou Fongo-Tongo 2e 14 Nkong-Ni BafouMssamif 1eir Fontem Dschang Penka-Michel Bamendjou Poumougne Foumbot MenouaFokoué Mbam-et-Kim Baham Djebem Santchou Bandja Batié Massangam Ngambé-Tikar Nguti Koung-Khi 1 Banka Bangou Kekem Toko Kupe-Manenguba Melong Haut-Nkam Bangangté Bafang Bana Bangem Banwa Bazou Baré-Bakem Ndé 1 Bakou Deuk Mundemba Nord-Makombé Moungo Tonga Makénéné Konye Nkongsamba 1er Kon Ndian Tombel Yambetta Manjo Nlonako Isangele 5 1 Nkondjock Dikome Balue Bafia Kumba Mbam-et-Inoubou Kombo Loum Kiiki Kombo Itindi Ekondo Titi Ndikiniméki Nitoukou Abedimo Meme Njombé-Penja 9 Mombo Idabato Bamusso Kumba 1 Nkam Bokito Kumba Mbanga 1 Yabassi Yingui Ndom Mbonge Muyuka Fiko Ngambé 6 Nyanon Lekié West-Coast Sanaga-Maritime Monatélé 5 Fako Dibombari Douala 55 Buea 5e Massock-Songloulou Evodoula Tiko Nguibassal Limbe1 Douala 4e Edéa 2e Okola Limbe 2 6 Douala Dibamba Limbe 3 Douala 6e Wou3rei Pouma Nyong-et-Kellé Douala 6e Dibang Limbe 1 Limbe 2 Limbe 3 Dizangué Ngwei Ngog-Mapubi Matomb Lobo 13 54 1 Feedback: [email protected]/ [email protected] Data Source: OCHA Based on OSM / INC *Data collected from NFI/Shelter cluster 4W. -

Technique of Empire

CAST1543917 Techset Composition India (P) Ltd., Bangalore and Chennai, India 11/2/2018 Technique of empire: Colonisation through a state of exception Gerard Emmanuel Kamdem Kamga University of Pretoria & University of the Free State CONTACT: Gerard Emmanuel Kamdem Kamga, [email protected] Abstract The main argument of this article lies in its conceptual framing which is a contextualisation of the problem of exception in the colonial and ‘postcolonial’ period of Cameroon. The country was technically colonised by Germany and following the Versailles treaty, was later transferred to France and Britain under a mandate of the League of Nations. Following legal and historical investigations, I assess how the permanent recourse to a state of exception within the colony was central to Europeans’ tactics in their strategies of control and domination of colonised people. I further examine how the country’s colonial past strongly influences current state structures through a basic reliance on emergency laws which have become normalised to a point where the law’s force has been reduced to the zero point of its own content. Keywords state of exception; state of emergency; colonialism; Cameroon; violence; rule of law; human rights; democracy In this article,1 I intend to expand on a technique repeatedly used by French colonial authorities to weaken and annihilate the struggles of independence in Cameroon, a technique which is still in force today and aims essentially to sideline political challengers and paralyse democracy. This technique is a legal institution which appeared for the first time in medieval canon law and is currently known as a state of exception. -

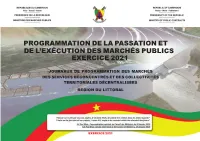

Programmation De La Passation Et De L'exécution Des Marchés Publics

PROGRAMMATION DE LA PASSATION ET DE L’EXÉCUTION DES MARCHÉS PUBLICS EXERCICE 2021 JOURNAUX DE PROGRAMMATION DES MARCHÉS DES SERVICES DÉCONCENTRÉS ET DES COLLECTIVITÉS TERRITORIALES DÉCENTRALISÉES RÉGION DU LITTORAL EXERCICE 2021 SYNTHESE DES DONNEES SUR LA BASE DES INFORMATIONS RECUEILLIES Nbre de N° Désignation des MO/MOD Montant des Marchés N° page Marchés 1 Services déconcentrés Régionaux 11 476 050 000 3 2 Communauté Urbaine de Nkongsamba 143 49 894 418 496 4 3 Communauté Urbaine de Nkongsamba 1 125 000 000 16 Département du Moungo 4 Services déconcentrés départementaux 2 38 000 000 17 5 Commune de BARE BAKEM 9 312 790 000 17 6 Commune de BONALEA 24 412 000 000 17 7 Commune de DIBOMBARI 11 273 300 000 19 8 Commune de LOUM 8 186 600 000 20 9 Commune de MANJO 8 374 700 000 21 10 Commune de MBANGA 9 222 600 000 21 11 Commune de MELONG 13 293 140 184 22 12 Commune de NJOMBE PENJA 5 221 710 000 23 13 Commune d'EBONE 10 294 400 000 24 14 Commune de MOMBO 6 142 500 000 24 15 Commune de NKONGSAMBA I 11 245 833 000 25 16 Commune de NKONGSAMBA II 11 316 000 000 26 17 Commune de NKONGSAMBA III 6 278 550 000 27 TOTAL Département 133 3 612 123 184 Département du Nkam 18 Services déconcentrés départementaux 2 16 000 000 28 19 Commune de NDOBIAN 12 309 710 000 28 20 Commune de NKONDJOCK 8 377 000 000 29 21 Commune de YABASSI 21 510 500 000 29 22 Commune de YINGUI 11 241 000 000 31 TOTAL Département 54 1 454 210 000 Département de la Sanaga Maritime 23 Services déconcentrés départementaux 10 371 600 000 32 24 Commune de Dibamba 13 328 650 000 32 -

Mongo Beti and Jean Marc ÛLa: Literary and Christian Liberation In

Santa Clara University Scholar Commons English College of Arts & Sciences 1994 Mongo Beti and Jean Marc Éla: Literary and Christian Liberation in Cameroon John C. Hawley Santa Clara Univeristy, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.scu.edu/engl Part of the English Language and Literature Commons, and the Social Justice Commons Recommended Citation Hawley, J. C. (1994). Mongo Beti and Jean Marc Éla: Literary and Christian Liberation in Cameroon. The Literary Griot: International Journal of Black Oral and Literary Studies 6(2), 14-23. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts & Sciences at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in English by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. , Mongo Beti and Jean-Marc Ela: The Literary and Christian Imagination in the Liberation of Cameroon John C. Hawley Santa Clara University In his fascinating study of contemporary African intellectuals and their struggle to set themselves apart from their European educations, K wame Anthony Appiah describes the intellectual ferment throughout the continent as producing "new, unpredictable fusions" because Africans "have the great advantage of having before [them] the European and American--and the Asian and Latin American--experiments with modernity to ponder as [they] make [their] choices" (134). Appiah uses the example of his own sister's wedding in Ghana to exemplify the hybridized role that religion continues to play in that self-definition. The ceremony followed the Methodist ritual; a Roman Catholic bishop offered the prayers, and Appiah's Oxford-educated relatives poured libations to their ancestors. -

INTERACTIVE FOREST ATLAS of CAMEROON Version 3.0 | Overview Report

INTERACTIVE FOREST ATLAS OF CAMEROON Version 3.0 | Overview Report WRI.ORG Interactive Forest Atlas of Cameroon - Version 3.0 a Design and layout by: Nick Price [email protected] Edited by: Alex Martin TABLE OF CONTENTS 3 Foreword 4 About This Publication 5 Abbreviations and Acronyms 7 Major Findings 9 What’s New In Atlas Version 3.0? 11 The National Forest Estate in 2011 12 Land Use Allocation Evolution 20 Production Forests 22 Other Production Forests 32 Protected Areas 32 Land Use Allocation versus Land Cover 33 Road Network 35 Land Use Outside of the National Forest Estate 36 Mining Concessions 37 Industrial Agriculture Plantations 41 Perspectives 42 Emerging Themes 44 Appendixes 59 Endnotes 60 References 2 WRI.org F OREWORD The forests of Cameroon are a resource of local, Ten years after WRI, the Ministry of Forestry and regional, and global significance. Their productive Wildlife (MINFOF), and a network of civil society ecosystems provide services and sustenance either organizations began work on the Interactive Forest directly or indirectly to millions of people. Interac- Atlas of Cameroon, there has been measureable tions between these forests and the atmosphere change on the ground. One of the more prominent help stabilize climate patterns both within the developments is that previously inaccessible forest Congo Basin and worldwide. Extraction of both information can now be readily accessed. This has timber and non-timber forest products contributes facilitated greater coordination and accountability significantly to the national and local economy. among forest sector actors. In terms of land use Managed sustainably, Cameroon’s forests consti- allocation, there have been significant increases tute a renewable reservoir of wealth and resilience. -

European Colonialism in Cameroon and Its Aftermath, with Special Reference to the Southern Cameroon, 1884-2014

EUROPEAN COLONIALISM IN CAMEROON AND ITS AFTERMATH, WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO THE SOUTHERN CAMEROON, 1884-2014 BY WONGBI GEORGE AGIME P13ARHS8001 BEING A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE SCHOOL OF POSTGRADUATE STUDIES, AHMADU BELLO UNIVERSITY, ZARIA, NIGERIA, IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF MASTER OF ARTS (MA) DEGREE IN HISTORY SUPERVISOR PROFESSOR SULE MOHAMMED DR. JOHN OLA AGI NOVEMBER, 2016 i DECLARATION I hereby declare that this Dissertation titled: European Colonialism in Cameroon and its Aftermath, with Special Reference to the Southern Cameroon, 1884-2014, was written by me. It has not been submitted previously for the award of Higher Degree in any institution of learning. All quotations and sources of information cited in the course of this work have been acknowledged by means of reference. _________________________ ______________________ Wongbi George Agime Date ii CERTIFICATION This dissertation titled: European Colonialism in Cameroon and its Aftermath, with Special Reference to the Southern Cameroon, 1884-2014, was read and approved as meeting the requirements of the School of Post-graduate Studies, Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria, for the award of Master of Arts (MA) degree in History. _________________________ ________________________ Prof. Sule Mohammed Date Supervisor _________________________ ________________________ Dr. John O. Agi Date Supervisor _________________________ ________________________ Prof. Sule Mohammed Date Head of Department _________________________ ________________________ Prof .Sadiq Zubairu Abubakar Date Dean, School of Post Graduate Studies, Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria. iii DEDICATION This work is dedicated to God Almighty for His love, kindness and goodness to me and to the memory of Reverend Sister Angeline Bongsui who passed away in Brixen, in July, 2012. -

Celebrating Unity and Debating Unity in Cameroon's 2010

Cahiers d’études africaines 218 | 2015 Varia Celebrating Unity and Debating Unity in Cameroon’s 2010 Independence Jubilees, the “Cinquantenaire” Les manifestations et le débat autour de l’idée de l’unité pendant les jubilés de l’indépendance du Cameroun en 2010 : le “Cinquantenaire” Kathrin Tiewa et Emmanuel Yenshu Vubo Édition électronique URL : http://journals.openedition.org/etudesafricaines/18128 DOI : 10.4000/etudesafricaines.18128 ISSN : 1777-5353 Éditeur Éditions de l’EHESS Édition imprimée Date de publication : 6 juillet 2015 Pagination : 331-358 ISSN : 0008-0055 Référence électronique Kathrin Tiewa et Emmanuel Yenshu Vubo, « Celebrating Unity and Debating Unity in Cameroon’s 2010 », Cahiers d’études africaines [En ligne], 218 | 2015, mis en ligne le 01 janvier 2015, consulté le 20 mars 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/etudesafricaines/18128 ; DOI : https://doi.org/ 10.4000/etudesafricaines.18128 © Cahiers d’Études africaines Kathrin Tiewa & Emmanuel Yenshu Vubo Celebrating Unity and Debating Unity in Cameroon’s 2010 Independence Jubilees, the “Cinquantenaire”* As 1st January 2010 was approaching the government of Cameroon prepared to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the country’s independence. Simultane- ously, Anglophones of all shades of political opinion and who make up roughly a fifth of the population were observed to openly question the rele- vance of the date when this applied only to the French speaking component of the polity (which had gained independence on 1st January 1960). Very close to that date the same government talked of the celebration of the independence and reunification of the two components of the bicultural and bilingual state and went ahead to effectively celebrate the event on the 20th of May 2010 (a date which had no relation to the two events). -

Ecam 4 Complementary Survey (Ec-Ecam 4)

REPUBLIQUE DU CAMEROUN REPUBLIC OF CAMEROON Paix- Travail- Patrie Peace- Work- Fatherland ------------------------- ------------------- INSTITUT NATIONAL DE NATIONAL INSTITUTE LA STATISTIQUE OF STATISTICS -------------------- ----------------- ECAM 4 COMPLEMENTARY SURVEY (EC-ECAM 4) DOCUMENT OF NOMENCLATURES August 2016 CONTENT PRESENTATION NOTE OF THE NOMENCLATURES....................................................... 3 NOMENCLATURE OF ADMINISTRATIVES UNITS ......................................................... 4 NOMENCLATURE OF EMPLOYMENTS, PROFESSIONS AND TRADES..................... 12 NOMENCLATURE OF ECONOMIC ACTIVITIES ............................................................. 30 NOMENCLATURE OF ACTIVITIES AND PRODUCTS.................................................... 36 NOMENCLATURE OF SURVEY AREAS ........................................................................... 68 2 PRESENTATION NOTE OF THE NOMENCLATURES Various nomenclatures have been elaborated mainly in order to facilitate the organization of the data collection. Their aim for this survey is essentially to enable a harmonized codification of administrative units, activities and products and variables concerning the labour market in Cameroon. The present document includes the nomenclature of administrative units, employments, professions and trades, economic activities, activities and products and survey areas. Each of these nomenclatures concerns specific sections of the questionnaire. The nomenclature of administrative units concerns: o For the household -

Republique Du Cameroun Republic of Cameroon

REPUBLIQUE DU CAMEROUN REPUBLIC OF CAMEROON PAIX - TRAVAIL - PATRIE PEACE - WORK - FATHERLAND JOURNAL DES PROJETS PAR CHAPITRE, PROGRAMME, ACTION ET PROJET (DETAILS DES PROJETS D'INVESTISSEMENT) PROJECT LOG-BOOK PER HEAD, PROGRAMME, ACTION ET PROJECT(DETAILS OF INVESTMENT PROJECT) Exercice/ Financial year : 2016 Chapitre 07 MINISTERE DE L'ADMINISTRATION TERRITORIALE ET DE LA DECENTRALISATION Head MINISTRY OF TERRITORIAL ADMINISTRATION AND DECENTRALIZATION Programme 092 MODERNISATION DE L'ADMINISTRATION DU TERRITOIRE Code service: 2004 MODERNISATION OF TERRITORIAL ADMINISTRATION Action 04 OPTIMISATION DES CAPACITES OPERATIONNELLES DES AUTORITES ADMINISTRATIVES OPTIMIZING THE OPERATIONAL CAPACITIES ADMINISTRATIVE AUTHORITIES En Milliers de FCFA In Thousand CFAF Région/ Region Tache Num Montant AE Montant CP Année Structure Poste Comptable Localité Unité physique Mode gestion Gestionnaire Département/ Division Task Num AE Amount CP Amount Start Structure Accounting sta. Locality Unité physique Management Gestionnaire Year Arrondiss./ Sub-division Paragraphe Réhabilitation des Sous-Préfectures Projet/Project Rehabilitation of Sub-Divisional Offices Pouma: Réhabilitation Sous-Préfecture 6 100 6 100 2016 47 14 44 LITTORAL PERCEPTION POUMA 2220 222032 - Un Service Délégation SOUS-PREFET POUMA d’une autorité Automatique POUMA Pouma: Rehabilitation of the Sub-Divisional Office SOUS- SANAGA MARITIME administrative réhabilité PRÉFECTURE DE POUMA [Qté:1] POUMA Total Projet/Project 6 100 6 100 Total Action 6 100 6 100 Total Programme 6 100 6 100 Total -

Plan Communal De Développement De Ngambe

RÉPUBLIQUE DU CAMEROUN REPUBLIC OF CAMEROON PAIX-TRAVAIL– PATRIE PEACE –WORK – FATHERLAND ---------- ---------- MINISTÈRE DE L’ADMINISTRATION MINISTRY OF TERRITORIAL ADMINISTRATION TERRITORIALE ET DE LA AND DECENTRALIZATION DÉCENTRALISATION ---------- ---------- LITTORAL REGION RÉGION DU LITTORAL ---------- ---------- SANAGA MARITIME DIVISION DÉPARTEMENT DE LA SANAGA MARITIME ---------- ---------- NGAMBE COUNCIL COMMUNE DE NGAMBE PLAN COMMUNAL DE DÉVELOPPEMENT DE NGAMBE Réalisé avec l’appui Technique de L’ONG LUDEPRENA Financier du PNDP (LUTTE POUR DÉVELOPPEMENT ET LA PROTECTION DE L’ENVIRONNEMENT ET LA NATURE BP : 6798 Yaoundé Tel : 99 59 17 12/74 03 71 83 [email protected] Février 2012 VALIDATION DES AUTORITÉS VISA DU DÉLÉGUÉ DÉPARTEMENTAL DU MINEPAT VISA DU PRÉFET ii RESUME iii LISTE DES ABREVIATIONS ......................................................................................................................................................... vi LISTE DES TABLEAUX ..............................................................................................................................................................VIII LISTE DES PHOTOS ..................................................................................................................................................................VIII LISTES DES CARTES ................................................................................................................................................................VIII LISTES DES FIGURES ...............................................................................................................................................................VIII -

Cameroon: Fragile State?

CAMEROON: FRAGILE STATE? Africa Report N°160 – 25 May 2010 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...................................................................................................... i I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. 1 II. FROM MANDATE TO MODERN CAMEROON – CONTINUITIES OF POWER AND RESISTANCE ..................................................... 1 A. FROM GERMANY TO FRANCE AND BRITAIN TO INDEPENDENCE .................................................... 1 1. 1884-1945: the beginnings of modern Cameroon ........................................................................ 2 2. 1945-1955: the emergence of Cameroonian politics ................................................................... 3 3. 1955-1961: the turbulent path to independence ........................................................................... 5 B. INDEPENDENT CAMEROON 1961-1982: THE IMPERATIVES OF UNITY AND STABILITY .................. 7 1. The UPC’s annihilation and the establishment of a one-party state ............................................ 7 2. Centralisation of the state and all its powers ................................................................................ 8 3. Co-option, corruption and repression as a system of governance ................................................ 9 III. PAUL BIYA IN POWER: THE CHALLENGES OF PLURALISM ........................ 10 A. 1982-1990: FALSE START ......................................................................................................... -

DECRET N° 95/082 DU 24 AVRIL 1995 Portant Création De Communes Rurales

REPUBLIQUE DU CAMEROUN PAIX-TRAVAIL-PATRIE DECRET N° 95/082 DU 24 AVRIL 1995 Portant création de communes rurales LE PRESIDENT DE LA REPUBLIQUE, Vu la constitution; Vu la loi n° 74/23 du 5 décembre 1974 portant organisation communale; Vu la loi n° 78/015 du 15 Juillet 1978 portant création des communautés urbaines; Vu le décret n° 72/349 du 14 Juillet 1972 portant organisation administrative de la République du Cameroun et ses textes modificatifs subséquents; Vu le décret 77/203 du 29 juin 1977 déterminant les communes et leur ressort territorial; Vu les décrets n°92/187 du ler septembre 1992 et n°92/206 du 5 octobre 1992 portant création des arrondissements et districts et leurs textes modificatifs subséquents; Vu les décrets n° 92/127 du 26 Août 1992 et n° 93/321 du 25 Novembre 1993 portant création des communes urbaines et rurales; Vu le décret n° 92/207 du 5 octobre 1992 portant création des nouveaux départements; Vu le décret 94/010 du 12 janvier 1994 fixant le ressort territorial de certaines unités administratives. DECRETE: Article Premier: — Sont créées à compter de la date de signature du présent décret les communes rurales ci-après: PROVINCE DE L'ADAMAOUA Département du Mbéré Commune rurale de ngaoui, dont le siège est à Ngaoui. Le ressort territorial de la commune rurale de Ngaoui couvre celui du district de Ngaoui. Le ressort territorial de la commune rurale de Djohong est modifié en conséquence. PROVINCE DU CENTRE Département de la Lékié — Commune rurale de Batchenga, dont le siège est à Batchenga.