Orthoptics and Orthoptists: the War Years 1939 - 1945

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Price List of MALDIVES 23 07 2020

MALDIVES 23 07 2020 - Code: MLD200101a-MLD200115b Newsletter No. 1284 / Issues date: 23.07.2020 Printed: 25.09.2021 / 05:10 Code Country / Name Type EUR/1 Qty TOTAL Stamperija: MLD200101a MALDIVES 2020 Perforated €4.00 - - Y&T: 7398-7401 Mushrooms (Mushrooms (Coprinus comatus; FDC €6.50 - - Michel: 9135-9138 Morchella esculenta; Leccinum aurantiacum; Amanita Imperforated €15.00 - - pantherina)) FDC imperf. €17.50 - - Stamperija: MLD200101b MALDIVES 2020 Perforated €3.00 - - Y&T: 1455 Mushrooms (Mushrooms (Gyromitra esculenta) FDC €5.50 - - Michel: 9139 / Bl.1485 Background info: Boletus edulis) Imperforated €15.00 - - FDC imperf. €17.50 - - Stamperija: MLD200102a MALDIVES 2020 Perforated €4.50 - - Y&T: 7402-7405 Dinosaurs (Dinosaurs (Dilophosaurus wetherilli; FDC €7.00 - - Michel: 9150-9153 Tyrannosaurus rex; Stegosaurus stenops; Imperforated €15.00 - - Parasaurolophus walkeri)) FDC imperf. €17.50 - - Stamperija: MLD200102b MALDIVES 2020 Perforated €3.50 - - Y&T: 1456 Dinosaurs (Dinosaurs (Triceratops horridus) FDC €6.00 - - Michel: 9154 / Bl.1488 Background info: Tyrannosaurus rex; Parasaurolophus Imperforated €15.00 - - walkeri) FDC imperf. €17.50 - - Stamperija: MLD200103a MALDIVES 2020 Perforated €4.00 - - Shells (Shells (Turbo jourdani; Pecten vogdesi; Conus FDC €6.50 - - omaria; Tutufa bubo)) Imperforated €15.00 - - FDC imperf. €17.50 - - Stamperija: MLD200103b MALDIVES 2020 Perforated €3.00 - - Y&T: 1457 Shells (Shells (Pseudozonaria annettae) Background FDC €5.50 - - Michel: 9144 / Bl.1486 info: Murex pecten; Vokesimurex dentifer; -

Canadian Airmen Lost in Wwii by Date 1943

CANADA'S AIR WAR 1945 updated 21/04/08 January 1945 424 Sqn. and 433 Sqn. begin to re-equip with Lancaster B.I & B.III aircraft (RCAF Sqns.). 443 Sqn. begins to re-equip with Spitfire XIV and XIVe aircraft (RCAF Sqns.). Helicopter Training School established in England on Sikorsky Hoverfly I helicopters. One of these aircraft is transferred to the RCAF. An additional 16 PLUTO fuel pipelines are laid under the English Channel to points in France (Oxford). Japanese airstrip at Sandakan, Borneo, is put out of action by Allied bombing. Built with forced labour by some 3,600 Indonesian civilians and 2,400 Australian and British PoWs captured at Singapore (of which only some 1,900 were still alive at this time). It is decided to abandon the airfield. Between January and March the prisoners are force marched in groups to a new location 160 miles away, but most cannot complete the journey due to disease and malnutrition, and are killed by their guards. Only 6 Australian servicemen are found alive from this group at the end of the war, having escaped from the column, and only 3 of these survived to testify against their guards. All the remaining enlisted RAF prisoners of 205 Sqn., captured at Singapore and Indonesia, died in these death marches (Jardine, wikipedia). On the Russian front Soviet and Allied air forces (French, Czechoslovakian, Polish, etc, units flying under Soviet command) on their front with Germany total over 16,000 fighters, bombers, dive bombers and ground attack aircraft (Passingham & Klepacki). During January #2 Flying Instructor School, Pearce, Alberta, closes (http://www.bombercrew.com/BCATP.htm). -

OPERATION MARKET- GARDEN 1944 (1) the American Airborne Missions

OPERATION MARKET- GARDEN 1944 (1) The American Airborne Missions STEVEN J. ZALOGA ILLUSTRATED BY STEVE NOON © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com CAMPAIGN 270 OPERATION MARKET- GARDEN 1944 (1) The American Airborne Missions STEVEN J ZALOGA ILLUSTRATED BY STEVE NOON Series editor Marcus Cowper © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 5 The strategic setting CHRONOLOGY 8 OPPOSING COMMANDERS 9 German commandersAllied commanders OPPOSING FORCES 14 German forcesAllied forces OPPOSING PLANS 24 German plansAllied plans THE CAMPAIGN 32 The southern sector: 101st Airborne Division landingOperation Garden: XXX Corps The Nijmegen sector: 82nd Airborne DivisionGerman reactionsNijmegen Bridge: the first attemptThe demolition of the Nijmegen bridgesGroesbeek attack by Korps FeldtCutting Hell’s HighwayReinforcing the Nijmegen Bridge defenses: September 18Battle for the Nijmegen bridges: September 19Battle for the Nijmegen Railroad Bridge: September 20Battle for the Nijmegen Highway Bridge: September 20Defending the Groesbeek Perimeter: September 20 On to Arnhem?Black Friday: cutting Hell’s HighwayGerman re-assessmentRelieving the 1st Airborne DivisionHitler’s counteroffensive: September 28–October 2 AFTERMATH 87 THE BATTLEFIELD TODAY 91 FURTHER READING 92 INDEX 95 © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com The Void: pursuit to the German frontier, August 26 to September 11, 1944 26toSeptember11, August pursuittotheGermanfrontier, Void: The Allied front line, date indicated Armed Forces Nijmegen Netherlands Wesel N German front line, evening XXXX enth Ar ifte my First Fsch September 11, 1944 F XXXX XXX Westwall LXVII 1. Fsch XXX XXXX LXXXVIII 0 50 miles XXX 15 LXXXIX XXX Turnhout 0 50km LXXXVI Dusseldorf Ostend Brugge Antwerp Dunkirk XXX XXX Calais II Ghent XII XXX Cdn Br XXX Cologne GERMANY Br Maastricht First Fsch Brussels XXXX Seventh Bonn Boulognes BELGIUM XXX XXXX 21 Aachen LXXXI 7 XXXX First XXXXX Lille 12 September 4 Liège Cdn XIX XXX XXX XXX North Sea XXXX VII Namur VII LXXIV Second US B Koblenz Br St. -

CAF 3Rd Pursuit Squadron 70 Years Ago: Coastal

http://www.caffrenchwing.fr AIRSHOWCAF FRENCH WING - BULLETIN MENSUEL - MONTHLY NEWSLETTER http://www.lecharpeblanche.fr PUBLIC EDITION http://www.worldwarbirdnews.com found on Wikipedia. This well-known The men who were engaged in the Volume 20 - N°02 - February 2015 “free encyclopedia” should always raid knew this perfectly, yet carried be read with caution, if not outright out their orders without hesitation, for EDITORIAL skepticism. However, some of its which some paid the ultimate price. contents are actually quite good, he staff members of the French such as this “featured article” which As we are about to celebrate the 70th T Wing recently met at the Air & details a little-known yet important anniversary of the armistice, let us Space Museum in Le Bourget to aerial battle. not forget what our predecessors had prepare for this year’s events and to sacrifice to achieve victory, up to activities. A few members were What made the events of 9 February the very last days of the war. present as well. You will find in 1945 particularly tragic is that these columns details about the they could, and should, have been Enjoy your reading ! topics that were discussed as well avoided, especially at a time when as what decisions were made. the war was clearly coming to an end. - Bertrand Brown As always, we will need our members to help out, whether at meetings and airshows to man the PX and welcome the public, clean up the hangar and prepare the meals for the fly-in, or simply participate in the many daily chores that need to be done at the hangar or on the airplanes. -

August 20 2018

Offi ce 902 765 3505 Val Connell • Light Roadside • Heavy Towing • Wheel Lift & Flatbed • www.canex.ca Cell 902 840 1600 Broker / Owner Fax 902 765 2438 24 HOUR TOWING No Interest Toll Free SPECIALISTS IN: 1 866 514 3948 • Accidents • Lock Outs • Boosts • Breakdowns • Credit Plan Plus Email • Cars • Heavy Haulage • Tractors • Trucks • • Buses • Baby Barns • RV’s • Motor Homes • Your choice of NOT EVEN THE TAXES! [email protected] EXIT Realty Town and Country 14 Wing Greenwood O.A.C. www.valj.com Independently Owned & Operated www.morsetowing.ca Middleton Cell (902): Month terms 902-765-6994 www.dnd-hht.com 825-7026 the Vol. 39 No. 31 AuroraAUGUST 20, 2018 NO CHARGE www.auroranewspaper.com Air Reserve BMQ shows off success at grad parade Sara White, its success. Managing editor “This is a tremendous showing on the parade Colonel Mark Larsen’s con- square,” Larsen said during gratulations and encourage- the graduation parade. ment for August 10 graduates “This has been a great ex- of a Basic Military Qualifi ca- “I took a year off tion Course can be extended from high school to beyond the new aviators’ weigh my options and futures to that of the Royal decided to try the RCAF Canadian Air Force. Reserve. The most Twenty new Canadian amazing thing is the Armed Forces members were teamwork. We were all part of BMQ Serial 0283, an strangers, and now it Air Reserve-specific BMQ feels like we’ve known offered for the first time each other for years. at 5th Canadian Division “Short-term goals Support Base Detachment are easier to attain, but Aviators Melanie Julien-Foster (left) and Shawna Kelly steal a moment to take a selfie on the 600-metre range at 5th Aldershot. -

References Updated 21/03/21

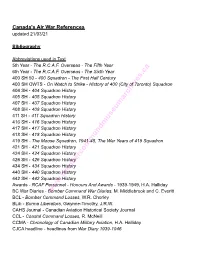

Canada's Air War References updated 21/03/21 Bibliography Abbreviations used in Text 5th Year - The R.C.A.F. Overseas - The Fifth Year 6th Year - The R.C.A.F. Overseas - The Sixth Year 400 SH 50 - 400 Squadron - The First Half Century 400 SH OWTS - On Watch to Strike - History of 400 (City of Toronto) Squadron 404 SH - 404 Squadron History 405 SH - 405 Squadron History 407 SH - 407 Squadron History 408 SH - 408 Squadron History 411 SH - 411 Squadron History 416 SH - 416 Squadron History 417 SH - 417 Squadron History 418 SH - 418 Squadron History 419 SH - The Moose Squadron, 1941-45, The War Years of 419 Squadron 421 SH - 421 Squadron History 424 SH - 424 Squadron History 426 SH - 426 Squadron History 434 SH - 434 Squadron History 440 SH - 440 Squadron History 442 SH - 442 Squadron History Awards - RCAF Personnel - Honours And Awards - 1939-1949, H.A. Halliday BC War Diaries - Bomberwww.bombercommandmuseumarchives.ca Command War Diaries, M. Middlebrook and C. Everitt BCL - Bomber Command Losses, W.R. Chorley BLib - Burma Liberators, Gwynne-Timothy, J.R.W. CAHS Journal - Canadian Aviation Historical Society Journal CCL - Coastal Command Losses, R. McNeill CCMA - Chronology of Canadian Military Aviation, H.A. Halliday CJCA headline - headlines from War Diary 1939-1946 CMA - Canadian Military Aircraft: Serials and Photographs 1920-1968 CWY - Chronology of the Winning Years, Aeroplane Monthly. FCL - Fighter Command Losses, N.L.R. Franks. FE - Fledgling Eagles, Shores, Foreman, Ehrengardt, Weiss & Olsen. FF Years - The R.C.A.F. Overseas - The First Four Years FP - Flight Patterns, Bilstein LH - Liddell Hart LoN - League of Nations Photo Archive, Timeline. -

Washington Evergreen

Fr~;E UP TO $2:.0.CO. OR 90 L'AY m J 'It FOl~ ~NT~_.::TlO>JAL INJURY. L ...:';'.L..:.tlFTf, OR DFi:;T1\{JC-UON (JI! . LlDI~ARY P!;OP(,L I'Y, Wash. Laws '35, P. 314, Sect. 16 Washington Evergreen VOL. XLVI z-799 STATE COLLEGE OF WASHINGTON, PULLMAN, WASH., WEDNESDAY, APRIL 17, 1940 No. 78 GREELEY AND PARRY NOMINATED --------------------------B Kappa Sig Alum PEACE OR WAR: Lecturer GUESTS: Photographer Suffers Gun Injury Students Select Paul Sax, From Desperadoes House Groups High School N at until two days after the al- Ace Clark as Candidates leged burglars attempted to break Will Observe Visitors Will into the United States post office in Millwood, was it revealed that Arnold Byram, who graduated from For Vice-President Office Washington State college last June, Peace Week Come Friday 'had been wounded in the neck by a shot fired from one of the bandit's Name Three Candidates for Secretary; gun. Religion and Life Campus Now Ready Byram is fighting for life in the Group Sponsors Webster, Schmitz, Diehl; Twenty-two Sacred Heart hospital in Spokane. To Show Delegates Nominees Vie for Ten Remaining Posts His condition is critical. His in- Group Meetings VISC :Hospitality juries were first described as entire- iy caused by the automobile in which Washington State's political melting pot was placed above the "It is black-out. In dim-blue Washington State will play election embers yesterday as one faction dominated by Greeks, the alleged burglars were fleeing. light, politicians as well as gen- Prosecuting Attorney Quacken- host this Week-end to more than the other composed of independen ts nominated men and women erals select the countries, the five hundred high school dele- for ASSCW offices for the forthcoming school year. -

Exclusive BLACK FRIDAY DEALS

VOTED ‘NO. 1 MONTHLY CRUISE MAGAZINE’ BY ALL LEADING CRUISE LINES Exclusive BLACK FRIDAY DEALS Incredible promotions only available for readers of Blue Horizons must end 8:00pm 30th November 2020 BH November Bonus 2020 - front cover.indd 1 05/11/2020 17:29 BOOK WITH CONFIDENCE WITH THE UK & IRELAND’S HELLO AND THE UK & IRELAND’S NO. 1 NOOCEAN.1 CRUISE OCEAN CRUISE SPECIALIST SPECIALIST We are proud to announce that WELCOME ROL Cruise has been named as the best agency for booking ocean cruise TO YOUR EXCLUSIVE holidays in the UK and Ireland. We were selected for the prestigious Top Ocean Cruise Agency title as part BLACK FRIDAY EDITION of a power-list of the nation’s best agents by industry bible, Travel Trade Gazette (TTG). OF BLUE HORIZONS Jeremy Dickinson, 5H SERVICE WITH ROL CRUISE Chairman of ROL Cruise hen the nights draw in the deals come out, which is why ROL Cruise are delighted to present this Exclusive Black Friday edition ‘EASIEST AND FRIENDLIEST WAY of Blue Horizons full of special offers: from TO BOOK A CRUISE HOLIDAY’ W exclusive additional savings to bonus Cruise Miles® When I talk to ROL, it is more like talking to a friend and special gifts. But hurry, these offers are only than a sales person. I have used them many times available until 8:00pm 30th November 2020! and it feels like we have a personal relationship. It’s an exciting time for one of the UK’s most loved They know what I want to do and always have cruise lines! Iconic Cunard are launching their all the information I need. -

Canada's Aviation Hall of Fame

Volume 32, No. 1 THE Winter 2014 Canada’s Aviation Hall of Fame Featured In This Issue: Introducing Inductees for 2014 (pages 4 & 5) More Photos of the Induction 2013 (pages 6 & 7) Special Guest Speaker Chris Hadfield (page 12) Clive Beddoe Lorna deBlicquy Robert Engle Fred Moore ST INDUCTION CEREMONY & DINNER 2 014 Thur., May 29, Calgary, AB Canada’s Aviation Hall of Fame Panthéon de l’Aviation du Canada CONTACT INFORMATION: BOARD OF DIRECTORS: Tom Appleton, ON, Chairman Canada’s Aviation Hall of Fame James Morrison, ON * NEW - P.O. Box 6090 Barry Marsden, BC, Vice-Chairman * NEW - Wetaskiwin, AB T9A 2E8 Canada Denis Chagnon, QC Phone: 780.361.1351 / Fax: 780.361.1239 Walter Chmela, ON Website: www.cahf.ca John Crichton, ON Email: see listings below: Bill Deluce, ON Blain Fowler, AB, Secretary, Treasurer STAFF: Miriam Kavanagh, ON Executive Director: Rosella Bjornson ([email protected]) Dwayne Lucas, BC Administrator: Dawn Lindgren ([email protected]) Mike Matthews, BC and ([email protected]) Anna Pangrazzi, ON Curator: Robert W. Reader, MLitt ([email protected]) Bill Elliot, Mayor of Wetaskiwin, AB (ex-officio) Assistant Executive Director: Robert Porter ([email protected]) OPERATIONS COMMITTEE: (Wetaskiwin) OFFICE HOURS: Blain Fowler, Chairman Tuesday - Friday: 9 am - 4:30 pm / Closed Mondays Rosella Bjornson John Chalmers CAHF DISPLAYS (HANGAR) HOURS: Perry McPherson Tuesday to Sunday: 10 am - 5 pm / Closed Mondays Denny May Winter Hours: 1 pm - 4 pm Marg May Please call to confirm opening times. Mary Oswald Robert Porter To change your address, contact The Hall at 780.361.1351, ext. -

Corporate Policing, Yellow Unionism, and Strikebreaking, 1890–1930

Corporate Policing, Yellow Unionism, and Strikebreaking, 1890–1930 This book provides a comparative and transnational examination of the complex and multifaceted experiences of anti-labour mobilisation, from the bitter social conflicts of the pre-war period, through the epochal tremors of war and revolution, and the violent spasms of the 1920s and 1930s. It retraces the formation of an extensive market for corporate policing, privately contracted security and yellow unionism, as well as processes of professionalisation in strikebreaking activities, labour espionage and surveillance. It reconstructs the diverse spectrum of right-wing patriotic leagues and vigilante corps which, in support or in competition with law enforcement agencies, sought to counter the dual dangers of industrial militancy and revolutionary situations. Although considerable research has been done on the rise of socialist parties and trade unions the repressive policies of their opponents have been generally left unexamined. This book fills this gap by reconstructing the methods and strategies used by state authorities and employers to counter outbreaks of labour militancy on a global scale. It adopts a long-term chronology that sheds light on the shocks and strains that marked industrial societies during their turbulent transition into mass politics from the bitter social conflicts of the pre-war period, through the epochal tremors of war and revolution, and the violent spasms of the 1920s and 1930s. Offering a new angle of vision to examine the violent transition to mass politics in industrial societies, this is of great interest to scholars of policing, unionism and striking in the modern era. Matteo Millan is associate professor of modern and contemporary history at the University of Padova, Italy. -

Rough Sailing in the U.S

(Periodicals postage paid in Seattle, WA) TIME-DATED MATERIAL — DO NOT DELAY News Arts & Style No green Christmas 100 years of Hun følte seg så forsømt som et for Norway? adventslys julaften. Kirsten Flagstad Read more on page 3 – Werner Mitsch Read more on page 13 Norwegian American Weekly Vol. 125 No. 44 December 6, 2013 Established May 17, 1889 • Formerly Western Viking and Nordisk Tidende $1.50 per copy News in brief Research Rough sailing in the U.S. Fast and effective re- establishment of biodiversity Sixty cadets from by the bauxite is mined in Paragominas – that is the goal of the Norwegian a comprehensive research project Naval Academy by three Brazilian research institutions, the University of got an ice-cold Oslo and Norwegian aluminium producer Hydro.The cooperation gift from the U.S. agreement with the University Marines as a of Oslo and the three Brazilian research institutions Federal surprise welcome University of Pará (UFPA), to America Federal Rural University of the Amazon (UFRA) and Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi (MPEG) SPECIAL RELEASE was signed in Belém, Brazil, on Royal Norwegian Embassy Friday. The collaboration will include research over a wide range of topics. After roughly three weeks of (Norway Post) sailing, the cadets had finally en- joyed their first weekend off, with time to explore northern Virginia. But now, on a day when the tem- Sports perature hovered around freezing, Norway won the Nordic they found themselves up to their Combined World Cup team event Photo: Wikimedia Commons at Kuusamo, Finland on Sunday, See > SAILING, page 6 The Statsraad Lehmkuhl serves as a floating classroom for the Norwegian Naval Academy. -

Fulton County News, January 3, 1941 Fulton County News

Murray State's Digital Commons Fulton County News Newspapers 1-3-1941 Fulton County News, January 3, 1941 Fulton County News Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.murraystate.edu/fca Recommended Citation Fulton County News, "Fulton County News, January 3, 1941" (1941). Fulton County News. 354. https://digitalcommons.murraystate.edu/fca/354 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Newspapers at Murray State's Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Fulton County News by an authorized administrator of Murray State's Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MAD FULTON SUNDAY AND MONDAY' GINGER ROGERS IN 'KITTY FOYLE' WITH DENNIS MORGAN o•-• JUSI 170 ADVERTISING FoR GOES HOME Jolt PRINTING FULTON COUNTY NEWS IN SERVICE Your Farm And Home Paper - Superior Coverage "THE NEWS" • V01111141E FULToN. K1., FRIDAV, JANUARV 3, 1941. IIBER FIFTY. Trisscl Waives - Liberty Church Will COURT CONVENES Local Bearing OUR DEMOCRACY by Mat Ham Meetings''41 RATES ANNOUNCED HERE JANUARY 1T ...at, 19, of Ohio, charged Liberty Baptist Church, of IN CROP PROGRAM with st,•,ihng a car belonging to whale Rev. L. M. Bratcher Jr., i$ John Adkins, Cleveland Avenue, pastor, will hold u series of meet- The January ti in of the Fulton Conservation payment rates sub- and breaking into Pickle's Gripe.•,e ings beginning Sunday, January county Circuit Court will mien dt istatitially the same as in 1940 and anti Coleman's Service Station 5, and continuing throughout the Hirk/Mil on Monday. January 20, a total acreage goal for all soil- day night, waived prelimmarv week.