Language Use and Language Contact in Brussels

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PDF Viewing Archiving 300

Bull. Soc. belge Géol., Paléont., Hydrol. T. 78 fasc. 2 pp. 111-130 Bruxelles 1969 Bull. Belg. Ver. Geol., Paleont., Hydrol. V. 78 deel 2 blz. 111-130 Brussel 1969 THE TYPE-LOCALITY OF THE SANDS OF GRIMMERTINGEN AND CALCAREOUS NANNOPLANKTON FROM THE LOWER TONGRIAN E. MARTINI 1 & T. MooRKENS 2 CONTENT Summary 111 Zusammenfassung 111 Résumé 112 1. Introduction . 112 2. Historical review of some chronostratigraphical conceptions. 114 3. The Eocene-Oligocene transitional strata in Belgium 115 4. Locality details 122 5. The calcareous nannoplankton assemblages 124 6. Conclusions . 125 7. Acknowledgments . 127 8. References 127 SuMMARY. A. DUMONT (1839-1849) considered the Sands of Grimmertingen as the base of his Ton grian stage (Grimmertingen is at present a hamlet in the municipality of Vliermaal in the Eastern part of Belgium). Samples have been taken from the outcrop of the type-locality and from a new boring reaching a depth of 12,5 m, towards the base of this member. Sorne of these sa.mples from both outcrop and boring yielded fairly rich assemblages of calcareous nannoplankton of which a list is given: the assemblages belong to the Ellipsolithus subdistichus zone, the zone which was also recognised in the sand extracted from the molluscs of the type-Latdorfian (Lower Oligocene). The recent sampling of the Grimmertingen-locality also permitted to find fairly rich associations of Hystrichospheres and of planktonic and benthonic Foraminifera, which are under current study. ZusAMMENFASSUNG. A. DUMONT (1839-1849) stellte die Sande von Grimmertingen an die Basis seines ,,Tongrien" (Grimmertingen befindet sich heute im Stadtbereich von Vliermaal im ostlichen Teil von Belgien). -

Public Fisheries Regulations 2018

FISHINGIN ACCORDANCE WITH THE LAW Public Fisheries Regulations 2018 ATTENTION! Consult the website of the ‘Agentschap voor Natuur en Bos’ (Nature and Forest Agency) for the full legislation and recent information. www.natuurenbos.be/visserij When and how can you fish? Night fishing To protect fish stocks there are two types of measures: Night fishing: fishing from two hours after sunset until two hours before sunrise. A large • Periods in which you may not fish for certain fish species. fishing permit of € 45.86 is mandatory! • Ecologically valuable waters where fishing is prohibited in certain periods. Night fishing is prohibited in the ecologically valuable waters listed on p. 4-5! Night fishing is in principle permitted in the other waters not listed on p. 4-5. April Please note: The owner or water manager can restrict access to a stretch of water by imposing local access rules so that night fishing is not possible. In some waters you might January February March 1 > 15 16 > 30 May June July August September October November December also need an explicit permit from the owner to fish there. Fishing for trout x x √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ x x x Fishing for pike and Special conditions for night fishing √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ pikeperch Always put each fish you have caught immediately and carefully back into the water of origin. The use of keepnets or other storage gear is prohibited. Fishing for other √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ species You may not keep any fish in your possession, not even if you caught that fish outside the night fishing period. Night fishing √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ Bobber fishing √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ Wading fishing x x √ √ x x √ √ √ √ √ √ x x x x Permitted x Prohibited √ Prohibited in the waters listed on p. -

Best Practices in Rural Development Flanders – Belgium

Best practices in rural development Flanders – Belgium Nominated and winning projects Competition Prima Plattelandsproject 2010 Preface At the beginning of April 2010, the Prima Plattelandsproject competition was launched. In the frame of this competition the Flemish Rural Network went in search of the best rural projects and activities in Flanders, subsidized under the Rural Development Programme 2007-2013 (RDP II). No fewer than 35 farmers or organisations submitted their candidacy. A total of 32 candidates were finally retained by the Flemish Rural Network. These were distributed as follows in function of the competition themes: - added value through cooperation: 15 candidates; - smart use of energy in agriculture and rural areas: 0 candidates; - care for nature and biodiversity: 8 candidates; - communication and education as an instrument: 6 candidates; - smart marketing strategies: 3 candidates. The provincial juries decided which of the submitted files could continue to the next round (up to 3 projects per theme per province). Then an international jury selected the five best candidates for each theme for the whole of Flanders. After that, everyone had the opportunity to vote for their favourite(s)on the www.ruraalnetwerk.be website. No less than 7300 valid votes were registered! The four winning projects were honoured on 14 January 2011 during an event at the Agriflanders agricultural fair. Picture: The four winning projects. Since all 18 projects can be considered “best practices”, this brochure gives an overview of the winning and the nominated projects by theme. The texts and photographs were provided by the applicants, unless otherwise indicated. Enjoy your read! Flemish Rural Network Theme “Added value through cooperation” WINNING PROJECT: Library service bus Zwevegem Project description: The main facilities (including the municipal administrative centre and the library) are located outside of the city centre in the municipality of Zwevegem, in the extreme north of the town. -

6 Second Periodical Report Presented to the Secretary General Of

Strasbourg, 26 May 2003 MIN-LANG/PR (2003) 6 EUROPEAN CHARTER FOR REGIONAL OR MINORITY LANGUAGES Second Periodical Report presented to the Secretary General of the Council of Europe in accordance with Article 15 of the Charter NETHERLANDS 1 CONTENTS Volume I: Second report on the measures taken by the Netherlands with regard to the Frisian language and culture (1999-2000-2001)............................................4 1 Foreword........................................................................................................4 2 Introduction...................................................................................................5 3 Preliminary Section.....................................................................................10 PART I .....................................................................................................................25 4 General measures.........................................................................................25 PART II .....................................................................................................................28 5 Objectives and principles.............................................................................28 PART III 31 6 Article 8: Education.....................................................................................31 7 Article 9: Judicial authorities.......................................................................79 8 Article 10: Administrative authorities and public services..........................90 10 Article -

Language Contact at the Romance-Germanic Language Border

Language Contact at the Romance–Germanic Language Border Other Books of Interest from Multilingual Matters Beyond Bilingualism: Multilingualism and Multilingual Education Jasone Cenoz and Fred Genesee (eds) Beyond Boundaries: Language and Identity in Contemporary Europe Paul Gubbins and Mike Holt (eds) Bilingualism: Beyond Basic Principles Jean-Marc Dewaele, Alex Housen and Li wei (eds) Can Threatened Languages be Saved? Joshua Fishman (ed.) Chtimi: The Urban Vernaculars of Northern France Timothy Pooley Community and Communication Sue Wright A Dynamic Model of Multilingualism Philip Herdina and Ulrike Jessner Encyclopedia of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism Colin Baker and Sylvia Prys Jones Identity, Insecurity and Image: France and Language Dennis Ager Language, Culture and Communication in Contemporary Europe Charlotte Hoffman (ed.) Language and Society in a Changing Italy Arturo Tosi Language Planning in Malawi, Mozambique and the Philippines Robert B. Kaplan and Richard B. Baldauf, Jr. (eds) Language Planning in Nepal, Taiwan and Sweden Richard B. Baldauf, Jr. and Robert B. Kaplan (eds) Language Planning: From Practice to Theory Robert B. Kaplan and Richard B. Baldauf, Jr. (eds) Language Reclamation Hubisi Nwenmely Linguistic Minorities in Central and Eastern Europe Christina Bratt Paulston and Donald Peckham (eds) Motivation in Language Planning and Language Policy Dennis Ager Multilingualism in Spain M. Teresa Turell (ed.) The Other Languages of Europe Guus Extra and Durk Gorter (eds) A Reader in French Sociolinguistics Malcolm Offord (ed.) Please contact us for the latest book information: Multilingual Matters, Frankfurt Lodge, Clevedon Hall, Victoria Road, Clevedon, BS21 7HH, England http://www.multilingual-matters.com Language Contact at the Romance–Germanic Language Border Edited by Jeanine Treffers-Daller and Roland Willemyns MULTILINGUAL MATTERS LTD Clevedon • Buffalo • Toronto • Sydney Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Language Contact at Romance-Germanic Language Border/Edited by Jeanine Treffers-Daller and Roland Willemyns. -

Memorandum Vlaamse En Federale

MEMORANDUM VOOR VLAAMSE EN FEDERALE REGERING INLEIDING De burgemeesters van de 35 gemeenten van Halle-Vilvoorde hebben, samen met de gedeputeerden, op 25 februari 2015 het startschot gegeven aan het ‘Toekomstforum Halle-Vilvoorde’. Toekomstforum stelt zich tot doel om, zonder bevoegdheidsoverdracht, de kwaliteit van het leven voor de 620.000 inwoners van Halle-Vilvoorde te verhogen. Toekomstforum is een overleg- en coördinatieplatform voor de streek. We formuleren in dit memorandum een aantal urgente vragen voor de hogere overheden. We doen een oproep aan alle politieke partijen om de voorstellen op te nemen in hun programma met het oog op het Vlaamse en federale regeerprogramma in de volgende legislatuur. Het memorandum werd op 19 december 2018 voorgelegd aan de burgemeesters van de steden en gemeenten van Halle-Vilvoorde en door hen goedgekeurd. 1. HALLE-VILVOORDE IS EEN CENTRUMREGIO Begin 2018 hebben we het dossier ‘Centrumregio-erkenning voor Vlaamse Rand en Halle’ met geactualiseerde cijfers gepubliceerd (zie bijlage 1). De analyse van de cijfers toont zwart op wit aan dat Vilvoorde, Halle en de brede Vlaamse Rand geconfronteerd worden met (groot)stedelijke problematieken, vaak zelfs sterker dan in andere centrumsteden van Vlaanderen. Momenteel is er slechts een beperkte compensatie voor de steden Vilvoorde en Halle en voor de gemeente Dilbeek. Dat is positief, maar het is niet voldoende om de problematiek, met uitlopers over het hele grondgebied van het arrondissement, aan te pakken. Toekomstforum Halle-Vilvoorde vraagt een erkenning van Halle-Vilvoorde als centrumregio. Deze erkenning zien we als een belangrijk politiek signaal inzake de specifieke positie van Halle-Vilvoorde. De erkenning als centrumregio moet extra financiering aanreiken waarmee de lokale besturen van de brede Vlaamse rand projecten en acties kunnen opzetten die de (groot)stedelijke problematieken aanpakken. -

Belgian Federalism After the Sixth State Reform by Jurgen Goossens and Pieter Cannoot

ISSN: 2036-5438 Belgian Federalism after the Sixth State Reform by Jurgen Goossens and Pieter Cannoot Perspectives on Federalism, Vol. 7, issue 2, 2015 Except where otherwise noted content on this site is licensed under a Creative Commons 2.5 Italy License E - 29 Abstract This paper highlights the most important institutional evolutions of Belgian federalism stemming from the implementation of the sixth state reform (2012-2014). This reform inter alia included a transfer of powers worth 20 billion euros from the federal level to the level of the federated states, a profound reform of the Senate, and a substantial increase in fiscal autonomy for the regions. This contribution critically analyses the current state of Belgian federalism. Although the sixth state reform realized important and long-awaited changes, further evolutions are to be expected. Since the Belgian state model has reached its limits with regard to complexity and creativity, politicians and academics should begin to reflect on the seventh state reform with the aim of increasing the transparency of the current Belgian institutional labyrinth. Key-words Belgium, state reform, Senate, constitutional amendment procedure, fiscal autonomy, distribution of powers, Copernican revolution Except where otherwise noted content on this site is licensed under a Creative Commons 2.5 Italy License E - 30 1. Introduction After the federal elections of 2010, Belgian politicians negotiated for 541 days in order to form the government of Prime Minister Di Rupo, which took the oath on 6 December 2011. This resulted in the (unofficial) world record of longest government formation period. After the Flemish liberal party (Open VLD) elicited the end of the government of Prime Minister Leterme, Belgian citizens had to vote on 13 June 2010. -

KIK-IRPA & AAT@Fr

KIK-IRPA & AAT@fr Plan to contribute French-language translation 7 September 2014 Dresden, ITWG-meeting Institut royal du Patrimoine artistique • Koninklijk Instituut voor het Kunstpatrimonium • Royal Institute for Cultural Heritage AAT@fr - Overview • Who? – KIK-IRPA & … • Why? – Momentum & needs • How? – Internal + external funding – International collaboration • When? – Now 7/09/2014 AAT@fr - Plan to contribute French-language translation of the Getty AAT 2 AAT@fr - Who? • KIK-IRPA: Royal Institute for Cultural Heritage – http://www.kikirpa.be/EN/ – http://balat.kikirpa.be/search_photo.php?lang=en-GB (Digital Art History) • Other Belgian (Scientific) Institutions – KMKG-MRAH: Royal Museums for Art & History (MULTITA project 2012-2014) – Fédération Bruxelles-Wallonie (terminology department) – Région wallonne (collaboration with KIK-IRPA for common thesaurus) • International – FRANTIQ: PACTOLS (http://frantiq.mom.fr/thesaurus-pactols) Institut des sciences humaines et sociales du CNRS = Centre national de la recherche scientifique – France: http://www.culture.gouv.fr/culture/inventai/patrimoine/ – Switzerland: hello – Canada (Québec): RCIP-CHIN (http://www.rcip-chin.gc.ca/index-fra.jsp) 7/09/2014 AAT@fr - Plan to contribute French-language translation of the Getty AAT 3 AAT@fr - Why? • Belgian particularities: bilingual (trilingual) country • KIK-IRPA: bilingual scientific institute • Disparate and uncomplete resources • Collaboration within AAT-NED • Several projects on multilingual terminologies • Because I want to ! 7/09/2014 AAT@fr -

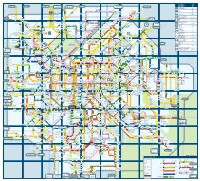

A 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 B C D E F G H I J a B C D E F G H

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 POINTS D’INTÉRÊT ARRÊT BEZIENSWAARDIGHEDEN HALTE Asse Puurs via Liezele Humbeek Mechelen Drijpikkel Puurs via Willebroek Luchthaven Malines Malderen Mechelen - Antwerpen POINT OF INTEREST STOP Dendermonde Boom via Londerzeel Kapelle-op-den-Bos Zone tarifaire MTB Tariefzone MTB Antwerpen Malines - Anvers Boom via Tisselt Verbrande Brug Anvers Stade Roi Baudouin Heysel B2 Koning Boudewijn stadion Heizel Jordaen Pellenberg Heysel Ennepetal Minnemolen Sportcomplex Kerk Vilvoorde Heldenplein Atomium B3 Vilvoorde Station 64 Heizel Vlierkens 260 47 58 Kerk Machelen 820 Machelen A 250-251 460-461 A 230-231-232 Twee Leeuwenweg Vilvoorde Heysel Blokken Brussels Expo B3 Zone tarifaire MTB Tariefzone MTB Koningin Fabiola Heizel VTM Drie Fonteinen Parkstraat Aéroport Bruxelles National Windberg Kasteel Luchthaven Brussel-Nationaal Brussels Airport B8 Zellik Station Twyeninck Witloof Beaulieu Raedemaekers Brussels National Airport Dilbeek Keebergen Kaasmarkt Robbrechts Cortenbach Kampenhout RTBF 243-820 Kerk Kortenbach Haacht Diamant D6 Hoogveld VRT Kerk Haren-Sud SAO DGHR Domaine Militaire Omnisports Haren 270-271-470 Markt Bever De Villegas Buda Haren-Zuid Omnisport Haren Basilique de Koekelberg Rijkendal Militair Hospitaal DOO DGHR Militair Domein Dobbelenberg Bossaert-Basilique Gemeenteplein Biplan Basiliek van Koekelberg E2 Guido Gezelle Vijvers Hôpital Militaire 47 Bicoque Aérodrome Bossaert-Basiliek Tweedekker Vliegveld Leuven National Basilica 820 Van Zone tarifaire MTB Louvain 240 Bloemendal Long Bonnier Beyseghem 53 57 -

Vlaamse Rand VLAAMSE RAND DOORGELICHT

Asse Beersel Dilbeek Drogenbos Grimbergen Hoeilaart Kraainem Linkebeek Machelen Meise Merchtem Overijse Sint-Genesius-Rode Sint-Pieters-Leeuw Tervuren Vilvoorde Wemmel Wezembeek-Oppem Zaventem Vlaamse Rand VLAAMSE RAND DOORGELICHT Studiedienst van de Vlaamse Regering oktober 2011 Samenstelling Diensten voor het Algemeen Regeringsbeleid Studiedienst van de Vlaamse Regering Cijferboek: Naomi Plevoets Georneth Santos Tekst: Patrick De Klerck Met medewerking van het Documentatiecentrum Vlaamse Rand Verantwoordelijke uitgever Josée Lemaître Administrateur-generaal Boudewijnlaan 30 bus 23 1000 Brussel Depotnummer D/2011/3241/185 http://www.vlaanderen.be/svr INHOUD INLEIDING ...................................................................................................................................................................................... 1 Algemene situering .................................................................................................................................................................... 2 1. Demografie ......................................................................................................................................................................... 4 1.1 Aantal inwoners neemt toe ............................................................................................................. 4 1.2 Aantal huishoudens neemt toe....................................................................................................... 5 1.3 Bevolking is relatief jong én vergrijst verder -

315 Bus Dienstrooster & Lijnroutekaart

315 bus dienstrooster & lijnkaart 315 Kraainem - Tervuren - Leefdaal - Leuven Bekijken In Websitemodus De 315 buslijn (Kraainem - Tervuren - Leefdaal - Leuven) heeft 4 routes. Op werkdagen zijn de diensturen: (1) Bertem Alsemberg: 07:50 (2) Bertem Oud Station: 12:00 (3) Leuven Station Perron 1: 05:45 - 18:45 (4) Sint- Lambrechts-Woluwe Kraainem Metro: 05:45 - 18:45 Gebruik de Moovit-app om de dichtstbijzijnde 315 bushalte te vinden en na te gaan wanneer de volgende 315 bus aankomt. Richting: Bertem Alsemberg 315 bus Dienstrooster 13 haltes Bertem Alsemberg Dienstrooster Route: BEKIJK LIJNDIENSTROOSTER maandag 07:50 dinsdag 07:50 Leuven Station Perron 10 perron 11 & 12, Leuven woensdag 07:50 Leuven J.Stasstraat donderdag 07:50 87 Bondgenotenlaan, Leuven vrijdag 07:50 Leuven Rector De Somerplein Zone B zaterdag Niet Operationeel 5 Margarethaplein, Leuven zondag Niet Operationeel Leuven Dirk Boutslaan 38 Dirk Boutslaan, Leuven Leuven De Bruul 4A Brouwersstraat, Leuven 315 bus Info Route: Bertem Alsemberg Leuven Sint-Rafaelkliniek Haltes: 13 18 Kapucijnenvoer, Leuven Ritduur: 18 min Samenvatting Lijn: Leuven Station Perron 10, Leuven Sint-Jacobsplein Leuven J.Stasstraat, Leuven Rector De Somerplein Sint-Jacobsplein, Leuven Zone B, Leuven Dirk Boutslaan, Leuven De Bruul, Leuven Sint-Rafaelkliniek, Leuven Sint-Jacobsplein, Leuven Tervuursepoort Leuven Tervuursepoort, Heverlee Egenhovenweg, 1 Herestraat, Leuven Heverlee Berg Tabor, Heverlee Sociaal Hogeschool, Heverlee Bremstraat, Bertem Alsemberg Heverlee Egenhovenweg 116 Tervuursesteenweg, -

Si Woluwe M'était Conté

Dossiers historiques Si Woluwe m’était conté ... Woluwe-Saint-Lambert Rédaction : Marc Villeirs, Musée communal Mise en page : Ariane Gauthier, service Information-Communication 2002. Si Woluwe m’était conté ... DOSSIER HISTORIQUE N°1 Les origines De Woluwe à Saint-Lambert, ou l'histoire du nom de notre commune Qui s'intéresse un tant Au-delà de 1203, les documents apparentée, Wiluva, existe dans soit peu à la toponymie nous livrent indifféremment les un manuscrit du milieu du XIe siè- (la science qui étudie les formes WOLUE (1238, 1282, 1352, cle mais qui désigne sans ambiguï- 1372, …) ou WOLUWE (1309, té Woluwe-Saint-Étienne. Des rai- noms de lieux) ne sera 1329, 1394, 1440,...). Cette derniè- sons similaires nous forcent à pas surpris de constater re s'impose toutefois progressive- rejeter Wileuwa et Wuluwa erro- la diversité surprenante ment au cours des temps et c'est nément cités en 1146 et 1186. de significations que elle qui devient la graphie officiel- revêtent les noms de nos le du nom de la communes. commune (de même que pour Certaines dénominations Saint-Étienne et sont aisément explica- Saint-Pierre) à bles. l'époque fran- Pour mémoire, citons : çaise. Aigremont, Blankenberge, Petite-Chapelle, Sint- On remarque qu'une graphie Ulriks-Kapelle, etc. excentrique, D'autres sont loin d'être Wilewe apparaît limpides : on y retrouve en 1163. Elle est la majorité des localités isolée et n'in- de nos régions. Il en est fluence donc enfin qui relèvent des pas les autres formes dont les deux catégories préci- La Woluwe à hauteur du parc des radicaux se présentent à l'unisson Sources vers 1930.