“You Can Live with Roman Character in Pigneto” a Qualitative Analysis of Authenticity in the Gentrifying Space

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

International Students Guide 2021 2022

Istituzione di Alta Formazione Artistica Musicale autorizzata con D.M. 144 del 1° agosto 2012 Ministero dell’Istruzione, dell’Università e della Ricerca STUDENT GUIDE Useful Information Before your departure and upon your arrival ---------------------------------------------------------------- Saint Louis College of Music Via Baccina, 47 - Via Urbana, 49/a - Via del Boschetto, 106 – Via Cimarra 19/b (00184, Roma) Tel +39 (0)6 4870017 - Fax +39 (0)6 91659362 www.slmc.it / www.saintlouiscollege.eu / [email protected] Sede legale: Via Cimarra 19b Roma Partita IVA 05731131008 – Registro Società del Tribunale di Roma n. 918703 . S i n c e 1 9 7 6 ---------------------------------------------------------------- Welcome to Saint Louis!………………………………………………………………… pag. 3 About Us….……………………………………………………………………………… pag. 3 Academic Programs……………………………………………………………………… pag. 3 Academic Calendar……………………………………………………………………… pag. 4 National Holidays and Breaks…………………………………………………………… pag. 4 Locations ………………………………………………………………………………… pag. 4 International Office ……………………………………………………………………… pag. 4 Orientation day…………………………………………………………………………… pag. 5 Dedicated services for Erasmus+ students ……………………………………………… pag. 5 CFA, ECTS and grading system ………………………………………………………… pag. 5 PRACTICAL INFORMATION Accommodation before arrival...………………………..……………………………… pag. 6 Visa / Residence Permit / Residence Registration ……………………………………… pag. 6 Codice fiscale…………………………………………………………………………… pag. 8 Health insurance ………………………………………………………………………… pag. 9 How to get to Saint Louis ……………………………………………………………… -

Carta Della Qualità Dei Servizi Del Trasporto Pubblico E Dei Servizi Complementari Atac 2019 Indice

Carta della qualità dei servizi del trasporto pubblico e dei servizi complementari Atac 2019 Indice Capitolo 1 – La Carta dei Servizi 3 1.1 La Carta dei Servizi: obiettivi 3 1.2 I Contratti di Servizio con Roma Capitale 3 1.3 Le Associazioni e il processo partecipativo 4 1.4 Le fonti normative e di indirizzo 4 Capitolo 2 – Atac si presenta 5 2.1 I principi dell’Azienda 5 3.2 Il trasporto pubblico su metropolitana 9 3.3 Sosta 19 3.4 Sicurezza 22 Capitolo 4 - L’attenzione alla qualità 23 4.1 La rendicontazione dell’attività di monitoraggio permanente 23 4.2 Gli indicatori di qualità erogata e programmata 23 4.3 Le segnalazioni degli utenti 30 4.4 Indagini di customer satisfaction 31 Capitolo 5 - La politica per il Sistema di Gestione di Atac SpA 34 5.1 Strategia aziendale 34 5.2 Salute e sicurezza degli utenti e tutela del patrimonio aziendale 34 5.3 Il rispetto dell’ambiente e l’uso razionale dell’energia 34 Capitolo 7 - Comunicazione e informazione 50 7.3 Nucleo Operativo sul Territorio 50 7.4 Altri canali di informazione e comunicazione 50 Appendice A - Diritti, doveri e condizioni generali di utilizzo dei servizi 57 2 Capitolo 1 La Carta dei Servizi 1.1 La Carta dei Servizi: obiettivi renza 1 agosto 2015; - Contratto di servizio per i servizi complementari al tra- La Carta della Qualità dei Servizi è il documento attraver- so il quale ogni ente erogatore di pubblici servizi assume una serie di impegni nei confronti della propria utenza, settembre 2017 con decorrenza 1 gennaio 2017. -

Mappa Partecipata Anello Verde

! MC Farnesina ! Parchi istituiti, urbani e territoriali MB1 Conca D'Oro MF Monte Antenne 31 ! ANELLO VERDE Aree verdi MAPPA PARTECIPATA Ambito ferroviario ! Stazioni ferroviarie esistenti e previste (PUMS) MF Campi Sportivi ! ! Stazioni metropolitane esistenti e previste (PUMS) FR Nomentana MF Acqua Acetosa ! ! MB1 Libia ! 16 Tessuti ed ambiti urbani in relazione diretta (locale) morfologica e funzionale 27 Piani attuativi oggetto di riorganizzazione n. Tematica Ambito Sintesi proposta MF Euclide 27 2 Luoghi da valorizzare Trastevere Realizzazione parcheggio interrato con parco urbano sovrastante ! 3 Interventi di traffic calming P.P. Sub Comprensorio Quadraro (ex SDO) Istituzione isola ambientale 27 AMBITI INTERESSATI DALLE PROPOSTE 4 Luoghi di aggregazione P.P. Sub Comprensorio Quadraro (ex SDO) Riqualificazione e riconversione a servizi di edificio della Regione Lazio MB1 S.Agnese/Annibaliano MB Rebibbia Valorizzazione area archeologica Parco Tiburtino, riqualificazione aree verdi esistenti e loro ! ! 5 Luoghi da valorizzare Comprensorio Tiburtino 27 connessione con parchi limitrofi Valorizzazione area archeologica Parco Tiburtino, riqualificazione aree verdi esistenti e loro 6 Luoghi da valorizzare Comprensorio Tiburtino Parchi e aree verdi da valorizzare connessione con parchi limitrofi Valorizzazione area archeologica Parco Tiburtino, riqualificazione aree verdi esistenti e loro 7 Luoghi da valorizzare Comprensorio Tiburtino 28 connessione con parchi limitrofi 27 Valorizzazione area archeologica Parco Tiburtino, riqualificazione -

Orari E Percorsi Della Linea Metro C

Orari e mappe della linea metro C Pantano - San Giovanni Visualizza In Una Pagina Web La linea metro C (Pantano - San Giovanni) ha 3 percorsi. Durante la settimana è operativa: (1) Monte Compatri-Pantano: 05:30 - 23:30 (2) San Giovanni: 05:30 - 23:30 Usa Moovit per trovare le fermate della linea metro C più vicine a te e scoprire quando passerà il prossimo mezzo della linea metro C Direzione: Monte Compatri-Pantano Orari della linea metro C 22 fermate Orari di partenza verso Monte Compatri-Pantano: VISUALIZZA GLI ORARI DELLA LINEA lunedì 05:30 - 23:30 martedì 05:30 - 23:30 San Giovanni Piazzale Appio, Roma mercoledì 05:30 - 23:30 Lodi giovedì 05:30 - 23:30 97 Via La Spezia, Roma venerdì 05:30 - 23:57 Pigneto sabato 00:06 - 23:57 Via del Pigneto, Roma domenica 00:06 - 23:30 Malatesta Piazza Roberto Malatesta, Roma Teano Informazioni sulla linea metro C Gardenie Direzione: Monte Compatri-Pantano Piazzale delle Gardenie, Roma Fermate: 22 Durata del tragitto: 32 min Mirti La linea in sintesi: San Giovanni, Lodi, Pigneto, Piazza dei Mirti, Roma Malatesta, Teano, Gardenie, Mirti, Parco Di Centocelle, Alessandrino, Torre Spaccata, Torre Parco Di Centocelle Maura, Giardinetti, Torrenova, Torre Angela, Torre Gaia, Grotte Celoni, Due Leoni-Fontana Candida, Alessandrino Borghesiana, Bolognetta, Finocchio, Graniti, Monte Via Casilina, Roma Compatri-Pantano Torre Spaccata Via di Tor Tre Teste, Roma Torre Maura Via Enrico Giglioli, Roma Giardinetti Via della Fattoria di Torrenova, Roma Torrenova Torre Angela Largo Ettore Paratore, Roma Torre Gaia Piazza -

Handout Directions ≥ 30 Sales Meeting

SALES MEETING 2021 DIRECTIONS ≥ 30 ROME, ITALY, 07-10 September ume Tevere FL3 ROMA Viterbo Viterbo FL1 Orte Viterbo Sacrofano Montebello Fara Sabina - Montelibretti La Giustiniana Piana Bella di Montelibretti Bracciano Prima Porta La Celsa Monterotondo - Mentana Vigna di Valle Labaro Settebagni Anguillara Centro Rai ARE Fidene NUL O A Cesano RD CO Saxa Rubra AC E R G ND Nuovo RA Olgiata RA ND G Grottarossa E Salario RA CC La Storta - Formello OR Due Ponti DO Due Ponti A N METRO ROME U La Giustiniana LA ume Tevere R Tor di Quinto E Ipogeo degli Ottavi Monte Antenne Mancini 2 Ottavia Jonio 2 Campi Sportivi Conca San Filippo Neri Conca d’Oro Acqua Acetosa d’Oro Monte Mario Libia 2 Gemelli Euclide Nomentana Balduina S.Agnese Rebibbia Appiano 19 3 Annibaliano Proba Petronia Ottaviano Valle Giulia 3.19 Ponte Mammolo VALLE TIBURTINA Monti S.Pietro 19 Tiburtini Battistini Cornelia AURELIA Musei Vaticani FLAMINIO Santa Maria del Soccorso Piazza del Popolo BOLOGNA Quintiliani Pietralata Baldo Cipro Lepanto 2 degli 19 Spagna Castro Policlinico Ubaldi Risorgimento Pretorio 3.19 RepubblicaRepubblica Palmiro La Rustica Teatrro OperaOpera Prenestina Togliatti Città Salone Lunghezza Aurelia Barberini Fontana Trevi TERMINI ume Tevere Tor Sapienza La Rustica Ponte FL5 SAN PIETRO 3.19 Serenissima FL2 5 14 UIR di Nona Civitavecchia Laziali Tivoli Grosseto Cavour Avezzano 8 S.Bibiana Vittorio Venezia 8 Emanuele Porta Maggiore Due Leoni/Fontana Candida Monte Compatri/Pantano Colosseo 3 5.14 Ponte Casilino 5.14.19 14 Manzoni 14 Vle P.Togliatti Museo della Liberazione3 -

MAPPA OHR2019.Pdf

M Jonio A Riserva Naturale I I C CORSOTOR DI FRANCIA DI QUINTO L dell’Insugherata C A V I U C A L S L L I E I F VIALE JONIO M I T A T I C A R R R A P L I MONTE SACRO E L E E D N D A O I VIA NOMENTANA I A V V VIA DEL CASALE DI S.BASILIO VIALE TOR DI QUINTO Conca D’oro Parco Petroselli V I A D E L F O R O I T A L I C O M V I V A Parco delle Valli I G . G I O VA N N I X X I I I A T I R L I GALLERIA GIOVANNI XXIIIN E O A T N F I I F R A O V R A L I E I E N V I A N O M N T E R O N T A VIALE ADRIATICO V I A L E K A N T A R M VIA DELLA CAMILLUCCIA O Università P A S I Cattolica del V I Sacro Cuore P PONTE MAMMOLO U N G O T E V E R M L A VIA TRIONFALE E D Piazza E L C L ’ Foro Italico A I Vescovio O C Parco Urbano E Q VIA SALARIA I C U D I di Aguzzano A T P A V I A T C A M E E N I T A H O L S T C N O A VIA FLAMINIA E C PA R I O L I M O A V I O S I A N D O E A I G A A T N I I T I Libia D E V S I M M N Villa Glori VIALE ERITREA O O I A L L G P Piazza L F Villa Ada Savoia A E L A E delle Muse D B L R A L E E N E L Palazzetto V I D A E MAXXI V I dello Sport VIA TIBURTINA T I A V A I O Auditorium L G V E N Parco della Musica U Stadio Piazza D V L Rebibbia E M I Flaminio Euclide Riserva Naturale A I V P I A T A R D I della Valle dell’Aniene I R O L P I I I E O O T N R N VIALE ERITREA F A A A I Piazza L C L A S E T I Istria S.Agnese / Annibaliano P I E T RA A L A T A R M P A A I I P I N C I A N O I Z Z VIALE LIEGI D V V VIA FLAMINIA I O O A L E B R U N O B U T R I E S T E L C Ponte Mammolo . -

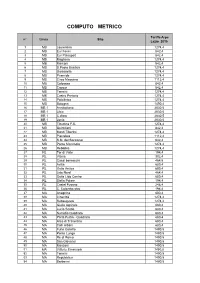

Computo Metrico

COMPUTO METRICO Tariffa Arpa n° Linea Sito Lazio 2015 1 MB Laurentina 1274,4 2 MB Eur Fermi 842,4 3 MB Eur Palasport 842,4 4 MB Magliana 1274,4 5 MB Marconi 842,4 6 MB S.Paolo Basilica 1274,4 7 MB Garbatella 1274,4 8 MB Piramide 1274,4 9 MB Circo Massimo 1112,4 10 MB Colosseo 842,4 11 MB Cavour 842,4 12 MB Termini 1274,4 13 MB Castro Pretorio 1274,4 14 MB Policlinico 1274,4 15 MB Bologna 1490,4 16 MB 1 Annibaliano 2030,5 17 MB 1 Libia 2030,5 18 MB 1 C.d'oro 2030,5 19 MB 1 Jonio 2030,5 20 MB Tiburtina F.S. 1274,4 21 MB Quintiliani 842,4 22 MB Monti Tiburtini 1274,4 23 MB Pietralata 1112,4 24 MB S.M. del Soccorso 842,4 25 MB Ponte Mammolo 1274,4 26 MB Rebibbia 1274,4 27 RL Tor di Valle 194,4 28 RL Vitinia 302,4 29 RL Casal bernocchi 464,5 30 RL Acilia 680,4 31 RL Ostia Antica 680,4 32 RL Lido Nord 464,4 33 RL Ostia Lido Centro 680,4 34 RL Stella Polare 194,4 35 RL Castel Fusano 248,4 36 RL C. Colombo staz 194,4 37 MA Anagnina 680,4 38 MA Cinecittà 1274,4 39 MA Subaugusta 1274,4 40 MA Giulio Agricola 680,4 41 MA Lucio Sestio 680,4 42 MA Numidio Quadrato 680,4 43 MA Porta Furba - Quadraro 680,4 44 MA Arco di Travertino 680,4 45 MA Colli Albani 680,4 46 MA Furio Camillo 1490,5 47 MA Ponte Lungo 1490,5 48 MA Re di Roma 1490,5 49 MA San Giovanni 1490,5 50 MA Manzoni 1490,5 51 MA Vittorio Emanuele 1490,5 52 MA Termini 1490,5 53 MA Repubblica 1490,5 54 MA Barberini 1490,5 55 MA Flaminio 1490,5 56 MA Lepanto 1490,5 57 MA Ottaviano 1490,5 58 MA Cipro 1274,4 59 MA Valle Aurelia 1274,4 60 MA Baldo degli Ubaldi 2030,5 61 MA Cornelia 2030,5 62 MA Mattia -

One Thing You Must Understand About Rome Is That It's Enormous and I

One thing you must understand about Rome is that it’s enormous and I can’t possibly explain everything here. For this reason, try to do some research before you go there and ask yourself what’s the purpose of your exchange. One location that is perfect for one person could be a nightmare for another. It’s very individual and you should try to adjust your stay in Rome so it suits perfectly for you. There’s a place here for every personality! I’m happy to answer specific questions, and you can find my mail address at the bottom of this document. My exchange semester in Rome was really something special. From the beginning I didn’t actually know what to expect. I had been in Rome maybe three or four times before as a tourist, and this time I was very excited to finally see this beautiful and big city with the perspective of the Roman citizens. As I already knew some Italian before my exchange period, one of my foremost goals was to improve my language skills. Hence, I found a place through Airbnb, where I lived together with one Italian woman that didn’t speak a single word of English. It was just perfect. I lived together with her in a big and beautiful apartment on the 7th floor, with an amazing and big terrace which had a view of south Rome and of the Roman hills. My biggest concern from the beginning was where to live. I asked myself questions several times such as if I want to live close to the university, close to the center, or in between. -

21.04.2015 Seminario E Visita Stazione Teano Linea C Metro C Scpa: Le Imprese E L’Oggetto Dell’Affidamento

21.04.2015 Seminario e Visita Stazione Teano Linea C Metro C scpa: le imprese e l’oggetto dell’affidamento Metro C è il Contraente Generale per la realizzazione “chiavi in mano” della nuova Linea C ed è costituita dalle seguenti imprese con mandataria Astaldi: Metro C scpa: il Contraente Generale Le imprese che costituiscono Metro C scpa sono aziende leader nel campo della costruzione di grandi opere civili e di infrastrutture di trasporto. Si caratterizzano per il know how acquisito nella costruzione di opere sotterranee, per la collaudata esperienza internazionale nella realizzazione di appalti con la formula General Contractor eperla produzione di sistemi di automazione e di materiale rotabile tecnologicamente avanzato. Metro C: la struttura dell’Appalto La Linea C: le date fondamentali e l’evoluzione Tracciato a base di gara Caratteristiche principali tratta Clodio/Mazzini ‐ Monte Compatri/Pantano Lunghezza della tratta 25,6 km Numero delle stazioni 30 Distanza media interstazione 800 m ca Lunghezza della linea in sotterraneo 16,9 km Lunghezza della linea all'aperto 8,7 km Stazioni di corrispondenza e scambio passeggeri con linee metro e linee ferroviarie esistenti: ‐2 con la Linea A della metropolitana: Ottaviano e S. Giovanni ‐ 1 con la Linea B della metropolitana: Colosseo ‐ 1 con la Ferrovia Regionale FR1 (Fiumicino aeroporto ‐ Fara Sabina): Pigneto Deposito/officina di Graniti su un'area di 220.000m² La Linea C: le date fondamentali e l’evoluzione 28 febbraio 2006 Aggiudicazione della gara all’ATI composta da Astaldi s.p.a, Vianini Lavori s.p.a., Consorzio Cooperative Costruzioni, Ansaldo Trasporti Sistemi Ferroviari s.p.a, che a norma del D. -

PRENESTINO Creating Connections: Reclaiming Lost Space and Reinforcing Social Bonds

PRENESTINO Creating Connections: Reclaiming Lost Space and Reinforcing Social Bonds Maddie Collins | Eli Learner | Helena Park | Joseph Reigle 2 Prenestino Preface Acknowledgements We want to acknowledge the vital guidance of our instructors Professor Nancy Brooks, Professor Greg Smith and Marco Gissara PhD., all of whom helped to contextualize our observations within local and contemporary academic perspectives. Additionally, we extend our gratitude to the individuals who were willing to speak to us for our interviews--Silvano and the bocce club members, Astro Nascente, Giulia Barra, Debora, Cristiana, Sabrina, Enzo, Marco, and Allesandra. 3 Table of Contents 1. Introduction 5 2. Overview 6 3. Historical Background 9 4. Methodology 14 5. Demographic Analysis 16 6. Physical Analysis 31 7. Community Engagement 45 8. Assessment and Recommendations 47 9. Bibliography 64 10. Appendix 65 4 Prenestino Introduction to Prenestino Introduction Our neighborhood study of Prenestino was conducted under the video call by Professor Greg Smith or our Teaching Assistant Marco Cornell in Rome Workshop course during the Spring 2020 semester. Gissara who could speak to residents in Italian and then translate Our class consisted of eight undergraduate students who were their notes into English for us. Additionally, we compensated for the separated into two groups of four to conduct separate neighborhood brief time we spent in the neighborhood itself through reflexive analyses. The neighborhood study is designed to provide students exercises such as cognitive mapping as well through virtual tools with opportunities for experiential and reflexive learning.1 Our such as Google Maps. This summary of our unique learning learning process went through stages of on the ground observations experience hopefully communicates the unavoidable limitations of in the neighborhood, statistical and policy analysis, interviews with our study. -

Bilancio Di Esercizio 2015 1

ROMA SERVIZI PER LA MOBILITÀ S.R.L BILANCIO DI ESERCIZIO 2015 1 INDICE RELAZIONE SULLA GESTIONE ........................................................................................................................................ 05 BILANCIO DI ESERCIZIO AL 31 DICEMBRE 2015 ....................................................................................................... 55 Stato Patrimoniale ................................................................................................................................................................... 56 Conto Economico ..................................................................................................................................................................... 59 Rendiconto Finanziario ............................................................................................................................................................. 60 NOTA INTEGRATIVA .............................................................................................................................................................. 63 Criteri di valutazione, principi contabili e principi di redazione del bilancio ....................................................................... 64 Altre informazioni ...................................................................................................................................................................... 67 Attività di direzione e coordinamento ................................................................................................................................... -

Fiches Ensembles

EDITORIAL The 21st century will be the first urban century innovative sources of funding and by ever. During the next decade, the part of world establishing narrow links with other aspects of population living in cities will reach the symbolic mobility: on a short term with parking and threshold of 50%. In the same time, people are road management policy and in the long term increasing their awareness of environmental with land use planning. issues and foresee the upcoming shortage of EMTA is an association of 32 such authorities fossil energy sources. Mobility demand and responsible for transport in European impacts on urban areas are then a growing metropolitan areas. concern for citizen and for decision makers. This second edition of the Directory describes In urban regions, particularly in dense areas, EMTA organisation and activities but further, public transport provides the most efficient aims at giving an overview of public transport mobility solution regarding both energy authorities in Europe, describing their evolution, consumption and scarce public space their environment and their undertakings. occupation. However, urban sprawling, generalisation of car ownership, especially in The detailed presentations of EMTA 32 Eastern European countries, congestion and members don’t necessarily allow direct shortage of available public funds are leading comparisons, which is the purpose of EMTA to a decreasing attractiveness of public Barometer, but demonstrate the huge variety transport but paradoxically are stressing its vital of legal frameworks, of institutional importance for the wealth of our cities. organisations, of funding schemes and of responsibilities shared with political bodies and Transport Authorities in the recent years have with operating companies.