Country Guidance: Afghanistan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Justice & Security Practices, Perceptions, and Problems in Kabul and Nangarhar

Justice & Security Practices, Perceptions, and Problems in Kabul and Nangarhar M AY 2014 Above: Behsud Bridge, Nangarhar Province (Photo by TLO) A TLO M A P P I N G R EPORT Justice and Security Practices, Perceptions, and Problems in Kabul and Nangarhar May 2014 In Cooperation with: © 2014, The Liaison Office. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, recording or otherwise without prior written permission of the publisher, The Liaison Office. Permission can be obtained by emailing [email protected] ii Acknowledgements This report was commissioned from The Liaison Office (TLO) by Cordaid’s Security and Justice Business Unit. Research was conducted via cooperation between the Afghan Women’s Resource Centre (AWRC) and TLO, under the supervision and lead of the latter. Cordaid was involved in the development of the research tools and also conducted capacity building by providing trainings to the researchers on the research methodology. While TLO makes all efforts to review and verify field data prior to publication, some factual inaccuracies may still remain. TLO and AWRC are solely responsible for possible inaccuracies in the information presented. The findings, interpretations and conclusions expressed in the report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Cordaid. The Liaison Office (TL0) The Liaison Office (TLO) is an independent Afghan non-governmental organization established in 2003 seeking to improve local governance, stability and security through systematic and institutionalized engagement with customary structures, local communities, and civil society groups. -

Progress in Afghanistan Bucharest Summit2-4 April 2008 Progress in Afghanistan

© MOD NL © MOD Canada © MOD Canada Progress in Afghanistan Progress in Bucharest Summit 2-4 April 2008 Bucharest Summit2-4 Progress in Afghanistan Contents page 1. Foreword by Assistant Secretary General for Public Diplomacy, ..........................1 Jean-François Bureau, and NATO Spokesman, James Appathurai 2. Executive summary .........................................................................................................................................2 3. Security ..................................................................................................................................................................... 4 • IED attacks and Counter-IED efforts 4 • Musa Qala 5 • Operations Medusa successes - Highlights Panjwayi and Zhari 6 • Afghan National Army 8 • Afghan National Police 10 • ISAF growth 10 4. Reconstruction and Development ............................................................................................... 12 • Snapshots of PRT activities 14 • Afghanistan’s aviation sector: taking off 16 • NATO-Japan Grant Assistance for Grassroots Projects 17 • ISAF Post-Operations Humanitarian Relief Fund 18 • Humanitarian Assistance - Winterisation 18 5. Governance ....................................................................................................................................................... 19 • Counter-Narcotics 20 © MOD Canada Foreword The NATO-led International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) mission is approaching five years of operations in Afghanistan. This report is a -

CB Meeting PAK/AFG

Polio Eradication Initiative Afghanistan Current Situation of Polio Eradication in Afghanistan Independent Monitoring Board Meeting 29-30 April 2015,Abu Dhabi AFP cases Classification, Afghanistan Year 2013 2014 2015 Reported AFP 1897 2,421 867 cases Confirmed 14 28 1 Compatible 4 6 0 VDPV2 3 0 0 Discarded 1876 2,387 717 Pending 0 0 *149 Total of 2,421 AFP cases reported in 2014 and 28 among them were confirmed Polio while 6 labelled* 123as Adequatecompatible AFP cases Poliopending lab results 26 Inadequate AFP cases pending ERC 21There Apr 2015 is one Polio case reported in 2015 as of 21 April 2015. Region wise Wild Poliovirus Cases 2013-2014-2015, Afghanistan Confirmed cases Region 2013 2014 2015 Central 1 0 0 East 12 6 0 2013 South east 0 4 0 Districts= 10 WPV=14 South 1 17 1 North 0 0 0 Northeast 0 0 0 West 0 1 0 Polio cases increased by 100% in 2014 Country 14 28 1 compared to 2013. Infected districts increased 2014 District= 19 from 10 to 19 in 2014. WPV=28 28 There30 is a case surge in Southern Region while the 25Eastern Region halved the number of cases20 in comparison14 to 2013 Most15 of the infected districts were in South, East10 and South East region in 2014. No of AFP cases AFP of No 1 2015 5 Helmand province reported a case in 2015 District= 01 WPV=01 after0 a period of almost two months indicates 13 14 15 Year 21continuation Apr 2015 of low level circulation. Non Infected Districts Infected Districts Characteristics of polio cases 2014, Afghanistan • All the cases are of WPV1 type, 17/28 (60%) cases are reported from Southern region( Kandahar-13, Helmand-02, and 1 each from Uruzgan and Zabul Province). -

Afghanistan State Structure and Security Forces

European Asylum Support Office Afghanistan State Structure and Security Forces Country of Origin Information Report August 2020 SUPPORT IS OUR MISSION European Asylum Support Office Afghanistan State Structure and Security Forces Country of Origin Information Report August 2020 More information on the European Union is available on the Internet (http://europa.eu). ISBN: 978-92-9485-650-0 doi: 10.2847/115002 BZ-02-20-565-EN-N © European Asylum Support Office (EASO) 2020 Reproduction is authorised, provided the source is acknowledged, unless otherwise stated. For third-party materials reproduced in this publication, reference is made to the copyrights statements of the respective third parties. Cover photo: © Al Jazeera English, Helmand, Afghanistan 3 November 2012, url CC BY-SA 2.0 Taliban On the Doorstep: Afghan soldiers from 215 Corps take aim at Taliban insurgents. 4 — AFGHANISTAN: STATE STRUCTURE AND SECURITY FORCES - EASO COUNTRY OF ORIGIN INFORMATION REPORT Acknowledgements This report was drafted by the European Asylum Support Office COI Sector. The following national asylum and migration department contributed by reviewing this report: The Netherlands, Office for Country Information and Language Analysis, Ministry of Justice It must be noted that the review carried out by the mentioned departments, experts or organisations contributes to the overall quality of the report, it but does not necessarily imply their formal endorsement of the final report, which is the full responsibility of EASO. AFGHANISTAN: STATE STRUCTURE AND SECURITY -

Child Friendly School Baseline Survey

BASELINE SURVEY OF CHILD-FRIENDLY SCHOOLS IN TEN PROVINCES OF AFGHANISTAN REPORT submitted to UNICEF Afghanistan 8 March 2014 Society for Sustainable Development of Afghanistan House No. 2, Street No. 1, Karti Mamorin, Kabul, Afghanistan +93 9470008400 [email protected] CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................... 1 1.1 BACKGROUND ........................................................................................................................ 1 1.2 STUDY MODIFICATIONS ......................................................................................................... 2 1.3 STUDY DETAILS ...................................................................................................................... 4 1.4 REPORT STRUCTURE ............................................................................................................... 6 2. APPROACH AND METHODOLOGY ........................................................................ 7 2.1 APPROACH .......................................................................................................................... 7 2.2 METHODOLOGY ................................................................................................................ 8 3. TRAINING OF FIELD STAFF ..................................................................................... 14 3.1 OVERVIEW ........................................................................................................................ -

The Kingdom of Afghanistan: a Historical Sketch George Passman Tate

University of Nebraska Omaha DigitalCommons@UNO Books in English Digitized Books 1-1-1911 The kingdom of Afghanistan: a historical sketch George Passman Tate Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/afghanuno Part of the History Commons, and the International and Area Studies Commons Recommended Citation Tate, George Passman The kingdom of Afghanistan: a historical sketch, with an introductory note by Sir Henry Mortimer Durand. Bombay: "Times of India" Offices, 1911. 224 p., maps This Monograph is brought to you for free and open access by the Digitized Books at DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Books in English by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Tate, G,P. The kfn&ean sf Af&mistan, DATE DUE I Mil 7 (7'8 DEDICATED, BY PERMISSION, HIS EXCELLENCY BARON HARDINGE OF PENSHURST. VICEROY AND GOVERNOR-GENERAL OF INDIA, .a- . (/. BY m HIS OBEDIENT, SERVANT THE AUTHOR. il.IEmtev 01 the Asiniic Society, Be?zg-nl, S?~rueyof I~din. dafhor of 'I Seisinqz : A Menzoir on the FJisio~y,Topo~rcrphj~, A7zliquiiies, (112d Peo$Ie of the Cozi?zt~y''; The F/.o?zlic7,.~ of Baluchisia'nn : Travels on ihe Border.? of Pe~szk n?zd Akhnnistnn " ; " ICalnf : A lMe??zoir on t7ze Cozl7~try and Fnrrzily of the Ahntadsai Khn7zs of Iinlnt" ; 4 ec. \ViTkI AN INrPR<dl>kJCTOl2Y NO'FE PRINTED BY BENNETT COLEMAN & Co., Xc. PUBLISHED AT THE " TIMES OF INDIA" OFFTCES, BOMBAY & C.1LCUTT-4, LONDON AGENCY : gg, SI-IOE LANE, E.C. -

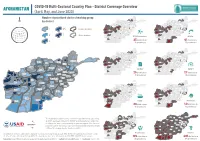

AFGHANISTAN COVID-19 Multi-Sectoral Country Plan - District Coverage Overview (April, May, and June 2020) Number of Prioritized Clusters/Working Group

AFGHANISTAN COVID-19 Multi-Sectoral Country Plan - District Coverage Overview (April, May, and June 2020) Number of prioritized clusters/working group Badakhshan Badakhshan Jawzjan Kunduz Jawzjan Kunduz Balkh Balkh N by district Takhar Takhar Faryab Faryab Samangan Samangan Sar-e-Pul Baghlan Sar-e-Pul Baghlan Panjsher Nuristan Panjsher Nuristan Badghis Parwan Badghis Parwan Bamyan Kapisa Kunar Bamyan Kapisa Kunar Laghman Laghman Kabul Kabul Maidan Wardak Maidan Wardak Ghor Nangarhar Ghor Nangarhar 1 4-5 province boundary Logar Logar Hirat Daykundi Hirat Daykundi Paktya Paktya Ghazni Khost Ghazni Khost Uruzgan Uruzgan Farah Farah Paktika Paktika 2 7 district boundary Zabul Zabul DTM Prioritized: WASH: Hilmand Hilmand Kandahar Kandahar Nimroz Nimroz 25 districts in 41 districts in 3 10 provinces 13 provinces Badakhshan Badakhshan Jawzjan Kunduz Jawzjan Kunduz Balkh Balkh Takhar Takhar Faryab Faryab Samangan Samangan Sar-e-Pul Baghlan Sar-e-Pul Baghlan Panjsher Nuristan Panjsher Nuristan Badghis Parwan Badghis Parwan Bamyan Kapisa Kunar Bamyan Kapisa Kunar Laghman Laghman Kabul Kabul Maidan Wardak Maidan Wardak Badakhshan Ghor Nangarhar Ghor Nangarhar Jawzjan Logar Logar Kunduz Hirat Daykundi Hirat Daykundi Balkh Paktya Paktya Takhar Ghazni Khost Ghazni Khost Uruzgan Uruzgan Farah Farah Paktika Paktika Faryab Zabul Zabul Samangan Baghlan Hilmand EiEWG: Hilmand ESNFI: Sar-e-Pul Kandahar Kandahar Nimroz Nimroz Panjsher Nuristan 25 districts in 27 districts in Badghis Parwan Bamyan Kapisa Kunar 10 provinces 12 provinces Laghman Kabul Maidan -

Humanitarian Overview - Farah Province OCHA Contact: Shahrokh Pazhman

Humanitarian Overview - Farah Province OCHA Contact: Shahrokh Pazhman February 2014 http://afg.humanitarianresponse.info/ Context: Farah province is the most contested in the Western Region with civilians in the northern, central and eastern districts significantly exposed to conflict between ANSF and AGEs. Basic services provision outside of the provincial capital is minimal. The province has few resources, while insecurity has affected the presence and activity of NGOs and the funding of Donors. Key Messages 1. The province has the highest risk profile in the Western Region and one of the highest for Afghanistan as a result of poor access to basic health services, restricted humanitarian access and exposure to drought. Insecurity severely hampers the delivery of basic services and humanitarian assistance to Bala Buluk, Bakwa, Gulistan, and Purchaman. More than a third of the population in the province suffers from poor access to health care centres and very low vaccination coverage. Access strategies as well institutional commitment by relevant departments are urgently required to improve this negative indicator. The limited presence of humanitarian organization must be offset by additional monitoring from Hirat-based regional clusters and regular engagement with provincial authorities. People in Need Population (CSO 2012) Humanitarian Organizations Transition Status Present with Current Operations 6,302 conflict IDPs from Total: 482,400 UNICEF, UNHCR, WHO, IOM, CHA, Fully transferred to the 2011 to 2013 (UNHCR) Male: 51.3% - Female: 48.7% VWO, ARCS, ICRC, and VARA Afghan National Army, 40,033 natural disaster Urban:7.3% - Rural: 92.7% 31 December 2012 affected from 2012 to 2013 (NATO). (IOM) 1,400 evicted from informal settlement (DoRR) plus 1,500 protracted IDPs living under tents since 1990s. -

Afghanistan – Baghlan Province Operational Coordination Team (OCT) Meeting ACTED Pul-E-Khumri Meeting Room on Wednesday 29 August 2018 at 09:00 Hrs

Afghanistan – Baghlan Province Operational Coordination Team (OCT) Meeting ACTED Pul-e-Khumri meeting room on Wednesday 29 August 2018 at 09:00 hrs Participants: UNICEF, ACTED, DACAAR, CTG/WFP, ORCD, AKF, FOCUS/AKAH, ANDMA, BDN, OCHA, DoRRD, DoRR # Agenda Issues Action Points Items 1 Welcome OCHA welcomed participants and appreciated humanitarian partners particularly Joint Assessment speech & Teams for their hard works and cooperation in ongoing assessment of vulnerable IDPs of Dand-e- opening Ghuri area of Pul-e-Khumri district. Afterwards each humanitarian agency shared their updates on remarks the recent humanitarian situation in Baghlan Province. 2 Update on ACTED: nowadays we have security problems in 6 districts such as (Pul-e-Khumri, Baghlan Jadid, ACTED was tasked to humanitarian Burka, Tala-wa-Barfak, Dahana-e-Ghuri and Doshi) districts and as usual the people are refer those rejected situation in displacing from their origin areas to different locations and they settle in rental and relative houses. petitions to UNHCR that Baghlan ACTED: recently on 06 Aug 2018, Baghlan IDPs Screening Committee Meeting took place and it their displacement are Province was agreed to assess all Dand-e-Ghuri IDP petitions. From 07-29 Aug, inter-agency assessment more than three months teams assessed 386 families and ERM partners verified only 50 families as eligible IDPs for in Pul-e-Khumri city. humanitarian assistance. Out of 50 families only 14 families are eligible for ERM criteria and other 36 families have been referred to WFP for food assistance. The meeting members agreed to refer those rejected petitions to UNHCR that their displacement are more than three months in Pul-e- Khumri city. -

Watershed Atlas Part IV

PART IV 99 DESCRIPTION PART IV OF WATERSHEDS I. MAP AND STATISTICS BY WATERSHED II. AMU DARYA RIVER BASIN III. NORTHERN RIVER BASIN IV. HARIROD-MURGHAB RIVER BASIN V. HILMAND RIVER BASIN VI. KABUL (INDUS) RIVER BASIN VII. NON-DRAINAGE AREAS PICTURE 84 Aerial view of Panjshir Valley in Spring 2003. Parwan, 25 March 2003 100 I. MAP AND STATISTICS BY WATERSHED Part IV of the Watershed Atlas describes the 41 watersheds Graphs 21-32 illustrate the main characteristics on area, popu- defined in Afghanistan, which includes five non-drainage areas lation and landcover of each watershed. Graph 21 shows that (Map 10 and 11). For each watershed, statistics on landcover the Upper Hilmand is the largest watershed in Afghanistan, are presented. These statistics were calculated based on the covering 46,882 sq. km, while the smallest watershed is the FAO 1990/93 landcover maps (Shapefiles), using Arc-View 3.2 Dasht-i Nawur, which covers 1,618 sq. km. Graph 22 shows that software. Graphs on monthly average river discharge curve the largest number of settlements is found in the Upper (long-term average and 1978) are also presented. The data Hilmand watershed. However, Graph 23 shows that the largest source for the hydrological graph is the Hydrological Year Books number of people is found in the Kabul, Sardih wa Ghazni, of the Government of Afghanistan – Ministry of Irrigation, Ghorband wa Panjshir (Shomali plain) and Balkhab watersheds. Water Resources and Environment (MIWRE). The data have Graph 24 shows that the highest population density by far is in been entered by Asian Development Bank and kindly made Kabul watershed, with 276 inhabitants/sq. -

Transfer of Authority Stage 4 Hospital Fire Fire Fighting Equipment

Transfer of Authority Stage 4 Hospital Fire at Mazar-e Sharif Fire Fighting Equipment for Lashkar Gah Fighting the Drought www.jfcbs.nato.int/ISAF 3. Commander’s Foreword 4. NATO unifies mission throughout Afghanistan Commander’s Foreword HAVE YOU GOT A STORY? HAVE YOU General Richards 5. Rough engineering made easy GOT A CAMERA? Then you could be 6. Turkish infirmary offers medical help one of the ISAF MIRROR journalists! Send your articles and photos about 7. 2,100 animals treated by the Italian ISAF activities and, who knows, you veterinary team could could be in the next issue. 8. French EOD team The ISAF Mirror is a Public Information 9. New wells and mosque for Meymaneh product. Articles, where possible, have been kept in their original form. Opinions 10. Patients rescued in hospital fire expressed are those of the writers and do not necessarily reflect official NATO, 14. Spanish PRT fights against drought JFC HQ Brunssum or ISAF policy. Photo 16. Three hundred children visit PRT credits are given to the authors of the Chaghcharan submission, unless otherwise stated. Submissions can be e-mailed to: 17. Repairs to Boghi Pul bridge [email protected] NATO’s fourth stage of expansion took place on 5 October. A fitting ceremony was held in Kabul to 18. Civil Affairs Team education support Articles should be in MS Word format mark ISAF’s assumption of responsibility for security – in support of the Government - in the eastern (Arial), photos should be at least 4.5cm provinces and, with that, responsibility for security across the whole territory of Afghanistan. -

Community- Based Needs Assessment

COMMUNITY- BASED NEEDS ASSESSMENT SUMMARY RESULTS PILOT ▪ KABUL As more IDPs and returnees urbanize and flock to cities, like Kabul, in search of livelihoods and security, it puts a strain on already overstretched resources. Water levels in Kabul have dramatically decreased, MAY – JUN 2018 forcing people to wait for hours each day to gather drinking water. © IOM 2018 ABOUT DTM The Displacement Tracking Matrix (DTM) is a system that HIGHLIGHTS tracks and monitors displacement and population mobility. It is districts assessed designed to regularly and systematically capture, process and 9 disseminate information to provide a better understanding of 201settlements with largest IDP and return the movements and evolving needs of displaced populations, populations assessed whether on site or en route. 828 In coordination with the Ministry of Refugees and Repatriation key informants interviewed (MoRR), in May through June 2018, DTM in Afghanistan piloted a Community-Based Needs Assessment (CBNA), intended as an 1,744,347 integral component of DTM's Baseline Mobility Assessment to individuals reside in the assessed settlements provide a more comprehensive view of multi-sectoral needs in settlements hosting IDPs and returnees. DTM conducted 117,023 the CBNA pilot at the settlement level, prioritizing settlements residents are returnees from abroad hosting the largest numbers of returnees and IDPs, in seven target 111,700 provinces of highest displacement and return, as determined by IDPs currently in host communities the round 5 Baseline Mobility Assessments results completed in mid-May 2018. DTM’s field enumerators administered the inter- 6,748 sectoral needs survey primarily through community focus group residents fled as IDPs discussions with key informants, knowledgeable about the living conditions, economic situation, access to multi-sectoral 21,290 services, security and safety, and food and nutrition, among residents are former IDPs who returned home other subjects.