Anne Hutchinson: a Life in Private

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wininger Family History

WININGER FAMILY HISTORY Descendants of David Wininger (born 1768) and Martha (Potter) Wininger of Scott County, Virginia BY ROBERT CASEY AND HAROLD CASEY 2003 WININGER FAMILY HISTORY Second Edition Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 87-71662 International Standard Book Number: 0-9619051-0-7 First Edition (Shelton, Pace and Wininger Families): Copyright - 2003 by Robert Brooks Casey. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be duplicated or reproduced in any manner without written permission of the authors. This book may be reproduced in single quantities for research purposes, however, no part of this book may be included in a published book or in a published periodical without written permission of the authors. Published in the United States by: Genealogical Information Systems, Inc. 4705 Eby Lane, Austin, TX 78731 Additional copies can be ordered from: Robert B. Casey 4705 Eby Lane Austin, TX 78731 WININGER FAMILY HISTORY 6-3 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ................6-1-6-8 Early Wininger Families ............6-9-6-10 Andrew Wininger (31) ............6-10 - 6-11 David Wininger (32) .............6-11 - 6-20 Catherine (Wininger) Haynes (32.1) ..........6-21 James S. Haynes (32.1.1) ............6-21 - 6-24 David W. Haynes (32.1.2) ...........6-24 - 6-32 Lucinda (Haynes) Wininger (32.1.3).........6-32 - 6-39 John Haynes (32.1.4) .............6-39 - 6-42 Elizabeth (Haynes) Davidson (32.1.5) ........6-42 - 6-52 Samuel W. Haynes (32.1.7) ...........6-52 - 6-53 Mary (Haynes) Smith (32.1.8) ..........6-53 - 6-56 Elijah Jasper Wininger (32.2) ...........6-57 Samuel G. -

Thomas Mayhew

“GOVERNOR FOR LIFE” THOMAS MAYHEW OF NANTUCKET AND MARTHA’S VINEYARD 1593 Thomas Mayhew was born. He would grow up in a town called Tisbury in Wiltshire, a tiny place between London and Bristol to the west. His father would die when he was 21 and he would become a merchant in the town in which he likely had been apprenticed, Southampton, due south, one of the great seaport towns of England. One of the London merchants who was very active in the colonization of New England was Matthew Cradock, and somehow Mayhew would become acquainted with Cradock and, after having been in business for himself for about 10 years, accept an offer in 1631 to become Cradock’s agent in the colonies. NANTUCKET ISLAND MARTHA’S VINEYARD HDT WHAT? INDEX GOVERNOR THOMAS MAYHEW THOMAS MAYHEW 1630 In England, William Coddington was chosen as an Assistant of the company (Assistant Judge of Court of Colony of Massachusetts Bay) before his embarkation with John Winthrop. He had lived at Boston in County Lincoln, where the record of St. Botolph’s church shows that he and his wife Mary Moseley Coddington, daughter of Richard Moseley of Ouseden, in County Suffolk had Michael Coddington, baptized on March 8, 1627, who died in two weeks, and Samuel Coddington, born on April 17, 1628, buried on August 21, 1629. The Winthrop fleet that brought “the Great Emigration” of this year comprised 11 vessels: • Arbella (the flagship) •Ambrose • William and Francis • Talbot • Hopewell • Jewel • Whale •Charles • Success • Mayflower •Trial Altogether the fleet brought about 700 colonists — here is an attempt at reconstructing a passenger list. -

Ocm01251790-1863.Pdf (10.24Mb)

u ^- ^ " ±i t I c Hon. JONATHAN E. FIELD, President. 1. —George Dwight. IJ. — K. M. Mason. 1. — Francis Briwiej'. ll.-S. .1. Beal. 2.— George A. Shaw. .12 — Israel W. Andrews. 2.—Thomas Wright. 12.-J. C. Allen. 3. — W. F. Johnson. i'i. — Mellen Chamberlain 3.—H. P. Wakefield. 13.—Nathan Crocker. i.—J. E. Crane. J 4.—Thomas Rice, .Ir. 4.—G. H. Gilbert. 14.—F. M. Johnson. 5.—J. H. Mitchell. 15.—William L. Slade. 5. —Hartley Williams. 15—H. M. Richards. 6.—J. C. Tucker. 16. —Asher Joslin. 6.—M. B. Whitney. 16.—Hosea Crane. " 7. —Benjamin Dean. 17.— Albert Nichols. 7.—E. O. Haven. 17.—Otis Gary. 8.—William D. Swan. 18.—Peter Harvey. 8.—William R. Hill. 18.—George Whitney. 9.—.]. I. Baker. 19.—Hen^^' Carter. 9.—R. H. Libby. 19.—Robert Crawford. ]0.—E. F. Jeiiki*. 10.-—Joseph Breck. 20. —Samuel A. Brown. .JOHN MORIS?5KV, Sevii^aiU-ut-Anns. S. N. GIFFORU, aerk. Wigatorn gaHei-y ^ P=l F ISSu/faT-fii Lit Coiranoittoralllj of llitss3t|ttsttts. MANUAL FOR THE USE OF THE G-ENERAL COURT: CONTAINING THE RULES AND ORDERS OF THE TWO BRANCHES, TOGETHER WITH THE CONSTITUTION OF THE COMMONWEALTH, AND THAT OF THE UNITED STATES, A LIST OF THE EXECUTIVE, LEGISLATIVE, AND JUDICIAL DEPARTMENTS OF THE STATE GOVERNMENT, STATE INSTITUTIONS AND THEIR OFFICERS, COUNTY OFFICERS, AND OTHER STATISTICAL INFORMATION. Prepared, pursuant to Orders of the Legislature, BY S. N. GIFFORD and WM. S. ROBINSON. BOSTON: \yRIGHT & POTTER, STATE PRINTERS, No. 4 Spring Lane. 1863. CTommonbtaltfj of iBnssacf)useits. -

Pennsylvania Magazine of HISTORY and BIOGRAPHY

THE Pennsylvania Magazine OF HISTORY AND BIOGRAPHY Governor John Blackwell: His Life in England and Ireland OHN BLACKWELL is best known to American readers as an early governor of Pennsylvania, the most recent account of his J governorship having been published in this Magazine in 1950. Little, however, has been written about his services to the Common- wealth government, first as one of Oliver Cromwell's trusted cavalry officers and, subsequently, as his Treasurer at War, a position of considerable importance and responsibility.1 John Blackwell was born in 1624,2 the eldest son of John Black- well, Sr., who exercised considerable influence on his son's upbringing and activities. John Blackwell, Sr., Grocer to King Charles I, was a wealthy London merchant who lived in the City and had a country house at Mortlake, on the outskirts of London.3 In 1640, when the 1 Nicholas B. Wainwright, "Governor John Blackwell," The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography (PMHB), LXXIV (1950), 457-472.I am indebted to Professor Wallace Notestein for advice and suggestions. 2 John Blackwell, Jr., was born Mar. 8, 1624. Miscellanea Heraldica et Genealogica, New Series, I (London, 1874), 177. 3 John Blackwell, Sr., was born at Watford, Herts., Aug. 25, 1594. He married his first wife Juliana (Gillian) in 1621; she died in 1640, and was buried at St. Thomas the Apostle, London, having borne him ten children. On Mar. 9, 1642, he married Martha Smithsby, by whom he had eight children. Ibid.y 177-178. For Blackwell arms, see J. Foster, ed., Grantees 121 122, W. -

The Governors of Connecticut, 1905

ThegovernorsofConnecticut Norton CalvinFrederick I'his e dition is limited to one thousand copies of which this is No tbe A uthor Affectionately Dedicates Cbis Book Co George merriman of Bristol, Connecticut "tbe Cruest, noblest ana Best friend T €oer fia<T Copyrighted, 1 905, by Frederick Calvin Norton Printed by Dorman Lithographing Company at New Haven Governors Connecticut Biographies o f the Chief Executives of the Commonwealth that gave to the World the First Written Constitution known to History By F REDERICK CALVIN NORTON Illustrated w ith reproductions from oil paintings at the State Capitol and facsimile sig natures from official documents MDCCCCV Patron's E dition published by THE CONNECTICUT MAGAZINE Company at Hartford, Connecticut. ByV I a y of Introduction WHILE I w as living in the home of that sturdy Puritan governor, William Leete, — my native town of Guil ford, — the idea suggested itself to me that inasmuch as a collection of the biographies of the chief executives of Connecticut had never been made, the work would afford an interesting and agreeable undertaking. This was in the year 1895. 1 began the task, but before it had far progressed it offered what seemed to me insurmountable obstacles, so that for a time the collection of data concerning the early rulers of the state was entirely abandoned. A few years later the work was again resumed and carried to completion. The manuscript was requested by a magazine editor for publication and appeared serially in " The Connecticut Magazine." To R ev. Samuel Hart, D.D., president of the Connecticut Historical Society, I express my gratitude for his assistance in deciding some matters which were subject to controversy. -

Anne Hutchinson Trial Lesson Plan

Learn Through Experience Downloadable Reproducible eBooks Thank you for purchasing this eBook from www.socialstudies.com or www.teachinteract.com To browse more eBook titles, visit http://www.teachinteract.com/ebooks.html To learn more about eBooks, visit our help page at http://www.teachinteract.com/ebookshelp.html For questions, please e-mail [email protected] Free E-mail Newsletter–Sign up Today! To learn about new and notable titles, professional development resources, and catalogs in the mail, sign up for our monthly e-mail newsletter at http://www.teachinteract.com/ THE TRIAL OF ANNE HUTCHINSON A re-creation of a New England woman’s trial for heresy in 1637, challenging her unorthodox religious views BILL LACEY, author of THE TRIAL OF ANNE HUTCHINSON, has written for Interact since 1974. He has authored/edited more than 25 simulations, re-creations, and similar role- playing works. Among the items he has writ- ten, he is most proud of GREEKS, SKINS, and CHRISTENDOM. Bill uses many of his creations in his history classes at Fountain Valley High School in Fountain Valley, California. Copyright ©1992, 1980 Interact 10200 Jefferson Boulevard P.O. Box 802 Culver City, CA 90232 ISBN 978-1-57336-135-4 All rights reserved. Only those pages of this simulation intended for student use as hand- outs may be reproduced by the teacher who has purchased this teaching unit from Interact. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording—without prior written permission from the publisher. -

Providence in the Life of John Hull: Puritanism and Commerce in Massachusetts Bay^ 16^0-1680

Providence in the Life of John Hull: Puritanism and Commerce in Massachusetts Bay^ 16^0-1680 MARK VALERI n March 1680 Boston merchant John Hull wrote a scathing letter to the Ipswich preacher William Hubbard. Hubbard I owed him £347, which was long overdue. Hull recounted how he had accepted a bill of exchange (a promissory note) ftom him as a matter of personal kindness. Sympathetic to his needs, Hull had offered to abate much of the interest due on the bill, yet Hubbard still had sent nothing. 'I have patiently and a long time waited,' Hull reminded him, 'in hopes that you would have sent me some part of the money which I, in such a ftiendly manner, parted with to supply your necessities.' Hull then turned to his accounts. He had lost some £100 in potential profits from the money that Hubbard owed. The debt rose with each passing week.' A prominent citizen, militia officer, deputy to the General Court, and affluent merchant, Hull often cajoled and lectured his debtors (who were many), moralized at and shamed them, but never had he done what he now threatened to do to Hubbard: take him to court. 'If you make no great matter of it,' he warned I. John Hull to William Hubbard, March 5, 1680, in 'The Diaries of John Hull,' with appendices and letters, annotated by Samuel Jennison, Transactions of the American Anti- quarian Society, II vols. (1857; repn. New York, 1971), 3: 137. MARK \i\LERi is E. T. Thompson Professor of Church History, Union Theological Seminary, Richmond, Virginia. -

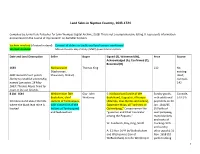

Land Sales in Nipmuc Country.Pdf

Land Sales in Nipmuc Country, 1643-1724 Compiled by Jenny Hale Pulsipher for John Wompas Digital Archive, 2018. This is not a comprehensive listing. It represents information encountered in the course of my research on Swindler Sachem. Sachem involved (if noted in deed) Consent of elders or traditional land owners mentioned Woman involved Massachusetts Bay Colony (MBC) government actions Date and Land Description Seller Buyer Signed (S), Witnessed (W), Price Source Acknowledged (A), ConFirmed (C), Recorded (R) 1643 Nashacowam Thomas King £12 No [Nashoonan, existing MBC General Court grants Shawanon, Sholan] deed; liberty to establish a township, Connole, named Lancaster, 18 May 142 1653; Thomas Noyes hired by town to lay out bounds. 8 Oct. 1644 Webomscom [We Gov. John S: Nodowahunt [uncle of We Sundry goods, Connole, Bucksham, chief Winthrop Bucksham], Itaguatiis, Alhumpis with additional 143-145 10 miles round about the hills sachem of Tantiusques, [Allumps, alias Hyems and James], payments on 20 where the black lead mine is with consent of all the Sagamore Moas, all “sachems of Jan. 1644/45 located Indians at Tantiusques] Quinnebaug,” Cassacinamon the (10 belts of and Nodowahunt “governor and Chief Councelor wampampeeg, among the Pequots.” many blankets and coats of W: Sundanch, Day, King, Smith trucking cloth and sundry A: 11 Nov. 1644 by WeBucksham other goods); 16 and Washcomos (son of Nov. 1658 (10 WeBucksham) to John Winthrop Jr. yards trucking 1 cloth); 1 March C: 20 Jan. 1644/45 by Washcomos 1658/59 to Amos Richardson, agent for John Winthrop Jr. (JWJr); 16 Nov. 1658 by Washcomos to JWJr.; 1 March 1658/59 by Washcomos to JWJr 22 May 1650 Connole, 149; MD, MBC General Court grants 7:194- 3200 acres in the vicinity of 195; MCR, LaKe Quinsigamond to Thomas 4:2:111- Dudley, esq of Boston and 112 Increase Nowell of Charleston [see 6 May and 28 July 1657, 18 April 1664, 9 June 1665]. -

Winthrop's Journal : "History of New England", 1630-1649

LIBRARY ^NSSACHt,^^^ 1895 Gl FT OF WESTFIELD STATE COLLEGE LIBRARY ORIGINAL NARRATIVES OF EARLY AMERICAN HISTORY REPRODUCED UNDER THE AUSPICES OF THE AMERICAN HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION General Editor, J. FRANKLIN JAMESON, Ph.D., LL.D. DIRECTOR OF THE DEPARTMENT OP HISTORICAL RESEARCH IN THE CAKNBGIB INSTITUTION OF WASHINGTON WINTHROFS JOURNAL 1630 — 1649 Volume I r"7 i-^ » '^1- **. '* '*' <>,>'•*'' '^^^^^. a.^/^^^^ ^Vc^^-f''f >.^^-«*- ^»- f^*.* vi f^'tiy r-^.^-^ ^4w;.- <i 4ossr, ^<>^ FIRST PAGE OF THE WINTHROP MANUSCRIPT From the original in the Library of the Massachusetts Historical Society ORIGINAL NARRATIVES OF EARLT AMERICAN HISTORY WINTHROP'S JOURNAL "HISTORY OF NEW ENGLAND" 1630—1649 EDITED BY JAMES KENDALL HOSMER, LLD. CORRESPONDING MEMBER OF THE MASSACHUSETTS HISTORICAL SOCIETY AND OF THE COLONIAL SOCIETY OF MASSACHUSETTS WITH MAPS AND FA CI ^^eStF^^ NORMAL SCHOOL VOLUME I CHARLES SCRIBNER'S SONS NEW YORK 1908 \^ c-4 COPYRIGHT, 1908, BY CHARLES SCRIBNER'S SONS Published June, 1908 \J . 1 NOTE While in this edition of Winthrop's Journal we have followed, as Dr. Hosmer explains in his Introduction, the text prepared by Savage, it has been thought wise to add devices which will make the dates easier for the reader to follow; but these have, it is hoped, been given such a form that the reader will have no difficulty in distinguishing added words or figures from those belonging to the original text. Winthrop makes no division into chapters. In this edition the text has, for the reader's convenience, been broken by headings repre- senting the years. These, however, in accordance with modern usage, have been set at the beginning of January, not at the date with which Winthrop began his year, the first of March. -

Ocm01251790-1865.Pdf (10.56Mb)

11 if (^ Hon. JONATHAN Ii'IBIiD, President. RIGHT. - - Blaisdell. - Wentworth. 11 Josiah C — Jacob H. Loud. 11. _ William L. Keed. Tappan -Martin Griffin. 12.- - Francis A. Hobart. — E. B. Stoddard. 12. — John S. Eldridge. - 2d. - Pitman. 1.3.- James Easton, — George Hej'wood. 13. — William VV.CIapp, Jr. Robert C. Codman. 14.- - Albert C Parsons. — Darwin E. 'Ware. 14. — Hiram A. Stevens. -Charles R - Kneil. - Barstow. 15.- Thomas — Francis Childs. 15 — Henr)' Alexander, Jr- Henry 16.- - Francis E. Parker. — Freeman Cobb. 16.— Paul A. Chadbourne. - George Frost. - Southwick. - Samuel M. Worcester. 17. Moses D. — Charles Adams, Jr. 17. — John Hill. 18. -Abiiah M. Ide. 18. — Eben A. Andrews. -Alden Leiand. — Emerson Johnson. Merriam. Pond. -Levi Stockbridge. -Joel — George Foster. 19. — Joseph A. Hurd. - Solomon C. Wells, 20. -Yorick G. — Miio Hildreth. S. N. GIFFORD, Clerk. JOHN MORISSEY. Serffeant-nt-Arms. Cflininontofaltl of llassadprfts. MANUAL FOR THE USE OP THE GENERAL COURT CONTAlN'mG THE RULES AND ORDERS OF THE TWO BRANCHES, TOGETHER WITH THE CONSTITUTION OF THE COMMONWEALTH, AND THAT OF THE UNITED STATES, A LIST OF THE EXECUTIVE, LEGISLATIVE, AND JUDICIAL DEPARTMENTS OF THE STATE GOVERNMENT, STATE INSTITUTIONS AND THEIR OFFICERS, COUNTY OFFICERS, AND OTHER STATISTICAL INFORMATION. i'C^c Prepared, pursuant to Orders of the Legislature, BY S. N. GIFFORD and WM. S. ROBINSON. BOSTON: \7RIGHT & POTTER, STATE PRINTERS, No. 4 Spring Lane. 186 5. Ccmmotttoealtfj of iHassncfjugetts. In Senate, January 10, 1865. Ordered, That the Clerks of the two branches cause to be printed and bound m suitable form two thousand copies of the Rules and Orders of the two branches, with lists of the several Standing and Special Committees, together with such other matter as has been prepared, in pursuance to an Order of the last legisla- ture. -

Endecott-Endicott Family Association, Inc. Volume 8 No

Endecott-Endicott Family Association, Inc. www.endecott-endicott.com Volume 8 No. 1 January, 2012 The Official EFA, Inc. Newsletter Endicott Heritage Trail © The Endicott Heritage Trail is being brought to you in an effort along with the EFA, Inc. web site to keep you informed of activities and projects of the Endecott-Endicott Family Association, Inc. We would appreciate your feedback. Your comments and suggestions are most welcome. We also welcome your contributions of Endicott research material. Please review the Newsletter Guidelines on the EFA, Inc. web site prior to your submission for publication. Ancestor’s Spotlight – John Endecott’s Military Service 1 by Teddy H. Sanford, Jr. MILITARY BACKGROUND IN THE OLD WORLD In his book, ―John Winthrop: America‘s Forgotten Founding Father,‖ the author, Francis J. Bremer, asserts the following. ―Historians have agreed that ENDECOTT had some European military experience, and the nature of the (Pequot) campaign suggests that he may have fought in England‘s Irish Wars.‖ Henry VIII was declared King of Ireland in 1530 and the next sixty years was spent in repressing the residents of that land. This became more difficult during the Anglo-Spanish War (1585-1604) that was started by the English when they intruded into Spanish Netherlands that led to memorable sea battles which included the defeat of the Spanish Armada in 1588. During the war, the Spanish meddled in the affairs of Ireland and the English were in conflict with them until the signing of the treaty in 1604 that ended English actions in 1 the Spanish Netherlands and Spain‘s support for dissidents in Ireland. -

Grandjean.Pdf

Web supplement for Katherine A. Grandjean, “New World Tempests: Environment, Scarcity, and the Coming of the Pequot War” Couriers Traveling between the Connecticut River Valley and Massachusetts Bay Name Letter Route Source From Connecticut to Massachusetts Bay Mr. Gibbons John Winthrop Jr. to John Winthrop, Apr. 7, 1636 Saybrook–Boston 3: 246–47 unnamed Englishman/shipmaster (the “Bacheler”) J. Winthrop Jr. to J. Winthrop, May 16, 1636 Saybrook–Boston 3: 260 John Haynes, W. Pynchon, and John Steele Roger Ludlow to J. Winthrop, May 29, 1638 Windsor–Boston 4: 36–37 “Panaquanike Indian” John Haynes to J. Wintrhop, Mar. 27, 1639 Wethersfield–Boston 4: 107 unnamed Englishman George Fenwick to J. Winthrop, Oct. 7, 1639 Connecticut–Boston 4: 141–42 “my seruant” William Pynchon to J. Winthop Jr., Apr. 22, 1636 Saybrook–Roxbury 3: 254–55 the “Wrenne” (mentioned) J. Winthrop to J. Winthrop Jr., June 23, 1636 Saybrook–Boston 3: 275–76 From Massachusetts Bay to Connecticut the “Rebecka” (mentioned) J. Winthrop to J. Winthrop Jr., Apr. 4, 1636 Boston–Saybrook 3: 244–45 John Oldham (by “Pinace”) J. Winthrop to J. Winthrop Jr., Apr. 4, 1636 Boston–Saybrook 3: 244–45 unnamed Indian (mentioned) Thomas Hooker to J. Winthrop, ca. December Boston–Hartford 4: 75–84 1638 Goodman Codmore, Goodman Grafton (mentioned) John Taylor to J. Winthrop, Sept. 28, 1640 Boston–Connecticut 4: 288 “This Shipp” J. Winthrop to J. Winthrop Jr., Apr. 26, 1636 Boston–Saybrook 3: 255–56 Mr. Hodges (mentioned) J. Winthrop to J. Winthrop Jr., Apr. 26, 1636 Boston–Saybrook 3: 255–56 Mr.