USDAFS Silvics of North America

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lepidoptera of North America 5

Lepidoptera of North America 5. Contributions to the Knowledge of Southern West Virginia Lepidoptera Contributions of the C.P. Gillette Museum of Arthropod Diversity Colorado State University Lepidoptera of North America 5. Contributions to the Knowledge of Southern West Virginia Lepidoptera by Valerio Albu, 1411 E. Sweetbriar Drive Fresno, CA 93720 and Eric Metzler, 1241 Kildale Square North Columbus, OH 43229 April 30, 2004 Contributions of the C.P. Gillette Museum of Arthropod Diversity Colorado State University Cover illustration: Blueberry Sphinx (Paonias astylus (Drury)], an eastern endemic. Photo by Valeriu Albu. ISBN 1084-8819 This publication and others in the series may be ordered from the C.P. Gillette Museum of Arthropod Diversity, Department of Bioagricultural Sciences and Pest Management Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO 80523 Abstract A list of 1531 species ofLepidoptera is presented, collected over 15 years (1988 to 2002), in eleven southern West Virginia counties. A variety of collecting methods was used, including netting, light attracting, light trapping and pheromone trapping. The specimens were identified by the currently available pictorial sources and determination keys. Many were also sent to specialists for confirmation or identification. The majority of the data was from Kanawha County, reflecting the area of more intensive sampling effort by the senior author. This imbalance of data between Kanawha County and other counties should even out with further sampling of the area. Key Words: Appalachian Mountains, -

Butterflies and Moths of Dorchester County, Maryland, United States

Heliothis ononis Flax Bollworm Moth Coptotriche aenea Blackberry Leafminer Argyresthia canadensis Apyrrothrix araxes Dull Firetip Phocides pigmalion Mangrove Skipper Phocides belus Belus Skipper Phocides palemon Guava Skipper Phocides urania Urania skipper Proteides mercurius Mercurial Skipper Epargyreus zestos Zestos Skipper Epargyreus clarus Silver-spotted Skipper Epargyreus spanna Hispaniolan Silverdrop Epargyreus exadeus Broken Silverdrop Polygonus leo Hammock Skipper Polygonus savigny Manuel's Skipper Chioides albofasciatus White-striped Longtail Chioides zilpa Zilpa Longtail Chioides ixion Hispaniolan Longtail Aguna asander Gold-spotted Aguna Aguna claxon Emerald Aguna Aguna metophis Tailed Aguna Typhedanus undulatus Mottled Longtail Typhedanus ampyx Gold-tufted Skipper Polythrix octomaculata Eight-spotted Longtail Polythrix mexicanus Mexican Longtail Polythrix asine Asine Longtail Polythrix caunus (Herrich-Schäffer, 1869) Zestusa dorus Short-tailed Skipper Codatractus carlos Carlos' Mottled-Skipper Codatractus alcaeus White-crescent Longtail Codatractus yucatanus Yucatan Mottled-Skipper Codatractus arizonensis Arizona Skipper Codatractus valeriana Valeriana Skipper Urbanus proteus Long-tailed Skipper Urbanus viterboana Bluish Longtail Urbanus belli Double-striped Longtail Urbanus pronus Pronus Longtail Urbanus esmeraldus Esmeralda Longtail Urbanus evona Turquoise Longtail Urbanus dorantes Dorantes Longtail Urbanus teleus Teleus Longtail Urbanus tanna Tanna Longtail Urbanus simplicius Plain Longtail Urbanus procne Brown Longtail -

Section 2. Jack Pine (Pinus Banksiana)

SECTION 2. JACK PINE - 57 Section 2. Jack pine (Pinus banksiana) 1. Taxonomy and use 1.1. Taxonomy The largest genus in the family Pinaceae, Pinus L., which consists of about 110 pine species, occurs naturally through much of the Northern Hemisphere, from the far north to the cooler montane tropics (Peterson, 1980; Richardson, 1998). Two subgenera are usually recognised: hard pines (generally with much resin, wood close-grained, sheath of a leaf fascicle persistent, two fibrovascular bundles per needle — the diploxylon pines); and soft, or white pines (generally little resin, wood coarse-grained, sheath sheds early, one fibrovascular bundle in a needle — the haploxylon pines). These subgenera are called respectively subg. Pinus and subg. Strobus (Little and Critchfield, 1969; Price et al., 1998). Occasionally, one to about half the species (20 spp.) in subg. Strobus are classified instead in a variable subg. Ducampopinus. Jack pine (Pinus banksiana Lamb.) and its close relative lodgepole pine (Pinus contorta Dougl. Ex Loud.) are in subg. Pinus, subsection Contortae, which is classified either in section Trifoliis or a larger section Pinus (Little and Critchfield, 1969; Price et al., 1998). Additionally, subsect. Contortae usually includes Virginia pine (P. virginiana) and sand pine (P. clausa), which are in southeastern USA. Jack pine has two quite short (2-5 cm) stiff needles per fascicle (cluster) and lopsided (asymmetric) cones that curve toward the branch tip, and the cone scales often have a tiny prickle at each tip (Kral, 1993). Non-taxonomic ecological or biological variants of jack pine have been described, including dwarf, pendulous, and prostrate forms, having variegated needle colouration, and with unusual branching habits (Rudolph and Yeatman, 1982). -

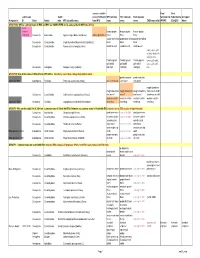

Common Names Working-2008Jan

correct scientific Final Final submission Subfa name (if different WFI common ESC common ESA common Submitted to Submitted to Accepted Assigned to: ID Order Family mily WFI scientific name from WFI) name name name CABI name info? WFIWC: ESA/ESC: Name GROUP 000: Official common name in ESA and ESC are COMPLETED and is same as that in WFI (take off list) need change? bronze poplar bronze poplar bronze poplar 1026-Bup Coleoptera Buprestidae Agrilus liragus Barter and Brown Agrilus granulatus borer borer borer poplar-and-willow poplar-and-willow poplar-and-willow Coleoptera Curculionidae Cryptorhynchus [Sternochetus] lapathi (L.) borer borer borer Coleoptera Curculionidae Nemocestes incomptus (Horn) woods weevil woods weevil wood weevil cooley spruce gall adelgid; douglas fir adelges; sitka Cooley spruce Cooley spruce Cooley spruce spruce gall aphid; gall aphid gall aphid gall aphid spruce gall aphid, Homoptera Adelgidae Adelges cooleyi (Gillette) (adelgid) (adelgid) (adelgid) blue GROUP 00: One of the names in ESA, ESC or WFI differs (Decide by case; likely change highlighted name) ponderosa pine ponderosa pine approved 1989 Lepidoptera Pyralidae Dioryctria auranticella (Grote) pine coneworm coneworm coneworm rough strawberry rough strawberry rough strawberry rough strawberry root weevil; rough Coleoptera Curculionidae Otiorhynchus rugosostriatus (Goeze) root weevil weevil root weevil strawberry weevil western conifer western conifer- western conifer- western conifer- approved 1989 Hemiptera Coreidae Leptoglossus occidentalis Heidemann seed -

Growth Response of Whitebark Pine (Pinus Albicaulis) Regeneration to Thinning and Prescribed Burn Release Treatments

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 2017 GROWTH RESPONSE OF WHITEBARK PINE (PINUS ALBICAULIS) REGENERATION TO THINNING AND PRESCRIBED BURN RELEASE TREATMENTS Molly L. McClintock Retzlaff Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Part of the Forest Management Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Retzlaff, Molly L. McClintock, "GROWTH RESPONSE OF WHITEBARK PINE (PINUS ALBICAULIS) REGENERATION TO THINNING AND PRESCRIBED BURN RELEASE TREATMENTS" (2017). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 11094. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/11094 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GROWTH RESPONSE OF WHITEBARK PINE (PINUS ALBICAULIS) REGENERATION TO THINNING AND PRESCRIBED BURN RELEASE TREATMENTS By MOLLY LINDEN MCCLINTOCK RETZLAFF Bachelor of Arts, University of Montana, Missoula, Montana, 2012 Thesis presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Forestry The University of Montana Missoula, MT December 2017 Approved by: Dr. Scott Whittenburg, Dean Graduate School Dr. David Affleck, Chair Department of Forest Management Dr. John Goodburn Department of Forest Management Dr. Sharon Hood USDA Forest Service Rocky Mountain Research Station © COPYRIGHT by Molly Linden McClintock Retzlaff 2017 All Rights Reserved ii Retzlaff, Molly, M.S., Winter 2017 Forestry Growth response of Whitebark pine (Pinus albicaulis) regeneration to thinning and prescribed burn release treatments Chairperson: Dr. -

Lepidoptera: Tortricidae: Tortricinae) and Evolutionary Correlates of Novel Secondary Sexual Structures

Zootaxa 3729 (1): 001–062 ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ Monograph ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2013 Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) http://dx.doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.3729.1.1 http://zoobank.org/urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:CA0C1355-FF3E-4C67-8F48-544B2166AF2A ZOOTAXA 3729 Phylogeny of the tribe Archipini (Lepidoptera: Tortricidae: Tortricinae) and evolutionary correlates of novel secondary sexual structures JASON J. DOMBROSKIE1,2,3 & FELIX A. H. SPERLING2 1Cornell University, Comstock Hall, Department of Entomology, Ithaca, NY, USA, 14853-2601. E-mail: [email protected] 2Department of Biological Sciences, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Canada, T6G 2E9 3Corresponding author Magnolia Press Auckland, New Zealand Accepted by J. Brown: 2 Sept. 2013; published: 25 Oct. 2013 Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0 JASON J. DOMBROSKIE & FELIX A. H. SPERLING Phylogeny of the tribe Archipini (Lepidoptera: Tortricidae: Tortricinae) and evolutionary correlates of novel secondary sexual structures (Zootaxa 3729) 62 pp.; 30 cm. 25 Oct. 2013 ISBN 978-1-77557-288-6 (paperback) ISBN 978-1-77557-289-3 (Online edition) FIRST PUBLISHED IN 2013 BY Magnolia Press P.O. Box 41-383 Auckland 1346 New Zealand e-mail: [email protected] http://www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ © 2013 Magnolia Press 2 · Zootaxa 3729 (1) © 2013 Magnolia Press DOMBROSKIE & SPERLING Table of contents Abstract . 3 Material and methods . 6 Results . 18 Discussion . 23 Conclusions . 33 Acknowledgements . 33 Literature cited . 34 APPENDIX 1. 38 APPENDIX 2. 44 Additional References for Appendices 1 & 2 . 49 APPENDIX 3. 51 APPENDIX 4. 52 APPENDIX 5. -

Verbenone Protects Chinese White Pine (Pinus Armandii)

Zhao et al.: Verbenone protects Chinese white pine (Pinus armandii) (Pinales: Pinaceae: Pinoideae) against Chinese white pine beetle (Dendroctonus armandii) (Coleoptera: Curculionidae: Scolytinae) attacks - 379 - VERBENONE PROTECTS CHINESE WHITE PINE (PINUS ARMANDII) (PINALES: PINACEAE: PINOIDEAE) AGAINST CHINESE WHITE PINE BEETLE (DENDROCTONUS ARMANDII) (COLEOPTERA: CURCULIONIDAE: SCOLYTINAE) ATTACKS ZHAO, M.1 – LIU, B.2 – ZHENG, J.2 – KANG, X.2 – CHEN, H.1* 1State Key Laboratory for Conservation and Utilization of Subtropical Agro-Bioresources (South China Agricultural University), Guangdong Key Laboratory for Innovative Development and Utilization of Forest Plant Germplasm, College of Forestry and Landscape Architecture, South China Agricultural University, Guangzhou 510642, China 2College of Forestry, Northwest A & F University, Yangling, Shaanxi 712100, China *Corresponding author e-mail: [email protected]; phone/fax: +86-020-8528-0256 (Received 29th Aug 2020; accepted 19th Nov 2020) Abstract. Bark beetle anti-aggregation is important for tree protection due to its high efficiency and fewer potential negative environmental impacts. Densitometric variables of Pinus armandii were investigated in the case of healthy and attacked trees. The range of the ecological niche and attack density of Dendroctonus armandii in infested P. armandii trunk section were surveyed to provide a reference for positioning the anti-aggregation pheromone verbenone on healthy P. armandii trees. 2, 4, 6, and 8 weeks after the application of verbenone, the mean attack density was significantly lower in the treatment group than in the control group (P < 0.01). At twelve months after anti-aggregation pheromone application, the mortality rate was evaluated. There was a significant difference between the control and treatment groups (chi-square test, P < 0.05). -

REJOINDER TU BRYANT MATHER Other Than Skippers, I Would Be Pleased to Know of It

• FOUNDED VOL.6; NO.2 1978 JULY 1984 THE OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF THE SOUTHERN LEPIDOPTERISTS' SOCIETY, ORGANIZED TO PROMOTE SCIENTIFIC INTEREST AND KNOWLEDGE RELATED TO UNDERSTANDING THE LEPIDOPTERA FAUNA OF THE SOUTHERN REGION OF THE UNITED STATES. REJOINDER TU BRYANT MATHER other than skippers, I would be pleased to know of it. Second, Mather dislikes the SOUTHERN LEPIDOPTERISTS' NEWS 5:1 arrangement of the photographs. This was Robert M. Pyle out of my hands and often at odds with my Swede Park, 369 Loop Road suggestions. Third, common (English) names Gray's River, WA 98621 Again I had no choice but to employ them, and therefore to coin some new ones. I at Thank you for the opportunity to reply tempted to use names that conveyed somethin to Bryant Mather's "Critique of the about the organism better than reiteration Audubon Field Guide" (SLN 5:1, May 1983, of the Latin or a patronym would do. If page 3). As with the remarks of scores Mather dislikes my choices, that is his pre of lepidopterists and others who have rogative. A joint Committee of the Xerces communicated with me about the book, Society and the Lepidopterists' Society is Bryant's comments are appreciated and I currently attempting to standardize English have duly noted them and forwarded them names for American butterflies, so a future to the editors for their consideration. edition my be able to rely on such a list. You were correct in your editorial note I certainly agree that the sole use of com when you explained that I was working mon names as photo captions is highly unfor under constraints imposed by the Chant tunate. -

Comparative Transcriptomics Among Four White Pine Species

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Previously Published Works Title Comparative Transcriptomics Among Four White Pine Species. Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7rn3g40q Journal G3 (Bethesda, Md.), 8(5) ISSN 2160-1836 Authors Baker, Ethan AG Wegrzyn, Jill L Sezen, Uzay U et al. Publication Date 2018-05-04 DOI 10.1534/g3.118.200257 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California INVESTIGATION Comparative Transcriptomics Among Four White Pine Species Ethan A. G. Baker,*,1 Jill L. Wegrzyn,*,1,2 Uzay U. Sezen,*,1 Taylor Falk,* Patricia E. Maloney,† Detlev R. Vogler,‡ Annette Delfino-Mix,‡ Camille Jensen,‡ Jeffry Mitton,§ Jessica Wright,** Brian Knaus,†† Hardeep Rai,‡‡ Richard Cronn,§§ Daniel Gonzalez-Ibeas,* Hans A. Vasquez-Gross,*** Randi A. Famula,*** Jun-Jun Liu,††† Lara M. Kueppers,‡‡‡,§§§ and David B. Neale***,2 *Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of Connecticut, Storrs, CT, †Department of Plant Pathology, University of California, Davis, CA, ***Department of Plant Sciences, University of California, Davis, CA, ‡USDA-Forest § Service, Pacific Southwest Research Station, Institute of Forest Genetics, Placerville, CA, Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of Colorado, Boulder, CO, **USDA-Forest Service Pacific Southwest Research Station, Davis, CA, ††US Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service, Horticultural Crop Research Unit, Corvallis, OR, §§ ‡‡Department of Biology, Utah State University, Logan, UT 84322, USDA-Forest Service Pacific -

Giovanny Fagua González

Phylogeny, evolution and speciation of Choristoneura and Tortricidae (Lepidoptera) by Giovanny Fagua González A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Systematics and Evolution Department of Biological Sciences University of Alberta © Giovanny Fagua González, 2017 Abstract Leafrollers moths are one of the most ecologically and economically important groups of herbivorous insects. These Lepidoptera are an ideal model for exploring the drivers that modulate the processes of diversification over time. This thesis analyzes the evolution of Choristoneura Lederer, a well known genus because of its pest species, in the general context of the evolution of Tortricidae. It takes an inductive view, starting with analysis of phylogenetic, biogeographic and diversification processes in the family Tortricidae, which gives context for studying these processes in the genus Choristoneura. Tectonic dynamics and niche availability play intertwined roles in determining patterns of diversification; such drivers explain the current distribution of many clades, whereas events like the rise of angiosperms can have more specific impacts, such as on the diversification rates of herbivores. Tortricidae are a diverse group suited for testing the effects of these determinants on the diversification of herbivorous clades. To estimate ancestral areas and diversification patterns in Tortricidae, a complete tribal-level dated tree was inferred using molecular markers and calibrated using fossil constraints. The time-calibrated phylogeny estimated that Tortricidae diverged ca. 120 million years ago (Mya) and diversified ca. 97 Mya, a timeframe synchronous with the rise of angiosperms in the Early-Mid Cretaceous. Ancestral areas analysis supports a Gondwanan origin of Tortricidae in the South American plate. -

Whitebark Pine Planting Guidelines

TECHNICAL NOTE Whitebark Pine Planting Guidelines Ward McCaughey, Glenda L. Scott, Kay L. Izlar This article incorporates new information into previous whitebark pine guidelines for planting prescriptions. Earlier 2006 guidelines were developed based on review of general literature, research studies, field observations, and standard US Forest Service survival surveys of high-elevation whitebark pine plantations. A recent study of biotic and abiotic factors affecting survival in whitebark pine plantations was conducted to determine survival rates over time and over a wide range of geographic locations. In these revised guidelines, we recommend reducing or avoiding overstory and understory competition, avoiding swales or frost pockets, providing shade and wind protection, protecting seedlings from heavy snow loads and soil movement, providing adequate growing space, avoiding ABSTRACT sites with lodgepole or mixing with other tree species, and avoiding planting next to snags. Keywords: Pinus albicaulis, reforestation, tree-planting, seedlings, plantations hitebark pine (Pinus albicaulis) is a keystone species in ing whitebark that show the potential for blister rust resistance are high-elevation ecosystems of the west. It has a wide geo- being attacked and killed by mountain pine beetles, thus accelerat- Wgraphic distribution (Tomback 2007) that includes the ing the loss of key mature cone-bearing trees. high mountains of western North America including the British Wildfire suppression has allowed plant succession to proceed Columbia Coastal Ranges, Cascade and Sierra Nevada ranges, and toward late successional communities, enabling species such as sub- the northern Rocky Mountains from Idaho and Montana and East alpine fir (Abies lasiocarpa) and Engelmann spruce (Picea engelman- to Wyoming (Schmidt 1994). -

Pinus Albicaulis Engelm. (Whitebark Pine) in Mixed-Species Stands Throughout Its US Range: Broad-Scale Indicators of Extent and Recent Decline

Article Pinus albicaulis Engelm. (Whitebark Pine) in Mixed-Species Stands throughout Its US Range: Broad-Scale Indicators of Extent and Recent Decline Sara A. Goeking 1,* ID and Deborah Kay Izlar 2 1 Inventory & Monitoring Program, Rocky Mountain Research Station, USDA Forest Service, 507 25th St., Ogden, UT 84401, USA 2 Resource Monitoring and Assessment, Pacific Northwest Research Station, USDA Forest Service, 1220 SW 3rd Avenue, Suite 1400, Portland, OR 97204, USA, [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-801-625-5193 Received: 30 January 2018; Accepted: 7 March 2018; Published: 9 March 2018 Abstract: We used data collected from >1400 plots by a national forest inventory to quantify population-level indicators for a tree species of concern. Whitebark pine (Pinus albicaulis) has recently experienced high mortality throughout its US range, where we assessed the area of land with whitebark pine present, size-class distribution of individual whitebark pine, growth rates, and mortality rates, all with respect to dominant forest type. As of 2016, 51% of all standing whitebark pine trees in the US were dead. Dead whitebark pines outnumbered live ones—and whitebark pine mortality outpaced growth—in all size classes ≥22.8 cm diameter at breast height (DBH), across all forest types. Although whitebark pine occurred across 4.1 million ha in the US, the vast majority of this area (85%) and of the total number of whitebark pine seedlings (72%) fell within forest types other than the whitebark pine type. Standardized growth of whitebark pines was most strongly correlated with the relative basal area of whitebark pine trees (rho = 0.67; p < 0.01), while both standardized growth and mortality were moderately correlated with relative whitebark pine stem density (rho = 0.39 and 0.40; p = 0.031 and p < 0.01, respectively).