Section 2. Jack Pine (Pinus Banksiana)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Effectiveness of Pheromone Mating Disruption for the Ponderosa

AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Christine G. Niwa for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Entomologypresented on October 24, 1988 Title: Effectiveness of Pheromone Mating Disruption for the Ponderosa Pine Tip Moth, Rhyacionia zozana (Kearfott) (Lepidoptera: Tortricidae), and its Influence on the Associated Parasite Complex Abstract approved: Redacted for Privacy ____(Garyy,w;Aterman Redacted for Privacy Tim DSchowalter The importance of pheromones in insect control relies both on their ability to reduce pest populations and on their relatively benign effects on nontarget organisms.This study was conducted to test the effectiveness of a pheromone application for mating disruption of the ponderosa pine tip moth, Rhyacionia zozana (Kearfott), and to determine if this treatment had any affect on the abundance or structure of the associated parasite complex. Chemical analyses, electroantennograms, and field bioassays showed that the most abundant pheromone component for R. zozana was E-9-dodecenyl acetate with a lesser amount of E-9-dodecenol also present. Acetate/alcohol ratios averaged 70:30 in gland washes; male moths were most attracted to sticky traps with synthetic baits containing ratios ranging from 70:30 to 95:5. Sixteen hymenopteran and one dipteran species of parasites were recovered from R. zozana larvae and pupae collected in Calif. and Oreg. Total percentage parasitism was high, averaging 47.2%. The ichneumonid, Glypta zozanae Walley and Barron, was the most abundant parasite, attacking over 30% of the hosts collected. Mastrus aciculatus (Provancher) was second in abundance, accounting for less than 4% parasitism. Hercon laminated-tape dispensers containing synthetic sex pheromone (a 95:5 mixture of E-9-dodecenyl acetate and E-9-dodecenol) were manually applied on 57 ha of ponderosa pine plantations in southern Oreg. -

A Practical Handbook for Determining the Ages of Gulf of Mexico And

A Practical Handbook for Determining the Ages of Gulf of Mexico and Atlantic Coast Fishes THIRD EDITION GSMFC No. 300 NOVEMBER 2020 i Gulf States Marine Fisheries Commission Commissioners and Proxies ALABAMA Senator R.L. “Bret” Allain, II Chris Blankenship, Commissioner State Senator District 21 Alabama Department of Conservation Franklin, Louisiana and Natural Resources John Roussel Montgomery, Alabama Zachary, Louisiana Representative Chris Pringle Mobile, Alabama MISSISSIPPI Chris Nelson Joe Spraggins, Executive Director Bon Secour Fisheries, Inc. Mississippi Department of Marine Bon Secour, Alabama Resources Biloxi, Mississippi FLORIDA Read Hendon Eric Sutton, Executive Director USM/Gulf Coast Research Laboratory Florida Fish and Wildlife Ocean Springs, Mississippi Conservation Commission Tallahassee, Florida TEXAS Representative Jay Trumbull Carter Smith, Executive Director Tallahassee, Florida Texas Parks and Wildlife Department Austin, Texas LOUISIANA Doug Boyd Jack Montoucet, Secretary Boerne, Texas Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries Baton Rouge, Louisiana GSMFC Staff ASMFC Staff Mr. David M. Donaldson Mr. Bob Beal Executive Director Executive Director Mr. Steven J. VanderKooy Mr. Jeffrey Kipp IJF Program Coordinator Stock Assessment Scientist Ms. Debora McIntyre Dr. Kristen Anstead IJF Staff Assistant Fisheries Scientist ii A Practical Handbook for Determining the Ages of Gulf of Mexico and Atlantic Coast Fishes Third Edition Edited by Steve VanderKooy Jessica Carroll Scott Elzey Jessica Gilmore Jeffrey Kipp Gulf States Marine Fisheries Commission 2404 Government St Ocean Springs, MS 39564 and Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission 1050 N. Highland Street Suite 200 A-N Arlington, VA 22201 Publication Number 300 November 2020 A publication of the Gulf States Marine Fisheries Commission pursuant to National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Award Number NA15NMF4070076 and NA15NMF4720399. -

Lepidoptera of North America 5

Lepidoptera of North America 5. Contributions to the Knowledge of Southern West Virginia Lepidoptera Contributions of the C.P. Gillette Museum of Arthropod Diversity Colorado State University Lepidoptera of North America 5. Contributions to the Knowledge of Southern West Virginia Lepidoptera by Valerio Albu, 1411 E. Sweetbriar Drive Fresno, CA 93720 and Eric Metzler, 1241 Kildale Square North Columbus, OH 43229 April 30, 2004 Contributions of the C.P. Gillette Museum of Arthropod Diversity Colorado State University Cover illustration: Blueberry Sphinx (Paonias astylus (Drury)], an eastern endemic. Photo by Valeriu Albu. ISBN 1084-8819 This publication and others in the series may be ordered from the C.P. Gillette Museum of Arthropod Diversity, Department of Bioagricultural Sciences and Pest Management Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO 80523 Abstract A list of 1531 species ofLepidoptera is presented, collected over 15 years (1988 to 2002), in eleven southern West Virginia counties. A variety of collecting methods was used, including netting, light attracting, light trapping and pheromone trapping. The specimens were identified by the currently available pictorial sources and determination keys. Many were also sent to specialists for confirmation or identification. The majority of the data was from Kanawha County, reflecting the area of more intensive sampling effort by the senior author. This imbalance of data between Kanawha County and other counties should even out with further sampling of the area. Key Words: Appalachian Mountains, -

JACK PINE Seedlings

Plant Guide snowshoe hares (Lepus americanus) feed on young JACK PINE seedlings. Porcupines (Erethizon dorsatum) feed on bark that often leads to deformed trees. Red squirrels Pinus banksiana Lamb. (Tamiasciurus hudsonicus), chipmunks (Eutamias Plant Symbol =PIBA2 spp.), mice (Peromyscus leucopus), goldfinches (Carduelis tristis), and robins (Turdus migratorius) Contributed by: USDA NRCS National Plant Data consume seeds. Center Status The Please consult the PLANTS Web site and your State Gooding Family’s Department of Natural Resources for this plant’s current status (e.g. threatened or endangered species, states noxious status, and wetland indicator values). 1st Annual Description Everybody Plays with Gooding General: Jack pine is a small to medium-sized, native, evergreen tree averaging 17 - 20 m (55 - 65 ft) Week: high. Crown small, irregularly rounded or spreading and flattened irregular. Branches descending to We Just don’t want to be spreading-ascending, poorly self-pruning; twigs slender, orange-red to red-brown, aging gray-brown, Lonely Days! rough. Cones are retained for several years, resulting in a coarse appearance. Trunk straight to crooked; bark at first dark and scaly, later develops scaly Celebrity Golf & ridges. Branchlets are yellow to greenish-brown when young, then turning gray-brown with age; very resinous buds. The leaves are evergreen, 2 - 3.75 cm Basketball (.75 - 1.5 in) long, and two twisted, divergent needles per fascicle, yellow-green in color all surfaces with Tournaments fine stomatal lines, margins finely serrulate, apex acute to short-subulate. Fascicle sheath is short 0.3- 0.6 cm, semipersistent. Seeds are compressed- Herman, D.E. et al. -

Formation of Primordia and Phyllotaxy Andrew J Fleming

Formation of primordia and phyllotaxy Andrew J Fleming Leaves are made in an iterative pattern by the shoot apical Introduction meristem. The mechanism of this pattern formation has Immediately after germination, plants have an apparently fascinated biologists, mathematicians and poets for simple structure. During the subsequent lifetime of the centuries. Over the past year, fundamental insights into the plant, this structure can become exquisitely ornate. This molecular basis of this process have been gained. Patterns of is as a result of the ability of the plant to continually auxin polar transport dictate when and where new leaf generate organs from a specialised structure, the apical primordia are formed on the surface of the apical meristem. meristem. The most common organ formed is the leaf. Subsequent events are still obscure but appear to involve both These organs are not generated in a random fashion, alteration of cell wall characteristics (to facilitate a new vector of rather in a consistent pattern over space and time, produc- growth) and a cascade of spatially co-ordinated transcription ing the regular architecture of the plant. The meristem is, factor activity (to determine the fate of cells that are thus, a pattern-generating machine. Recent research, incorporated into new lateral organs). The co-ordinated described in this review, has provided key insights into signalling events involved in these processes are beginning the operation of this machine. to be elucidated. Meristems provide a field of cells from Addresses which leaves can be made Department of Animal and Plant Sciences, University of Sheffield, The shoot apical meristem consists of a population of cells Western Bank, Sheffield S10 2TN, UK that functions to maintain itself and, at periodic intervals, Corresponding author: Fleming, Andrew J (a.fleming@sheffield.ac.uk) to generate a new organ (a leaf primordium) from its lateral boundary (Figure 1). -

Well-Known Plants in Each Angiosperm Order

Well-known plants in each angiosperm order This list is generally from least evolved (most ancient) to most evolved (most modern). (I’m not sure if this applies for Eudicots; I’m listing them in the same order as APG II.) The first few plants are mostly primitive pond and aquarium plants. Next is Illicium (anise tree) from Austrobaileyales, then the magnoliids (Canellales thru Piperales), then monocots (Acorales through Zingiberales), and finally eudicots (Buxales through Dipsacales). The plants before the eudicots in this list are considered basal angiosperms. This list focuses only on angiosperms and does not look at earlier plants such as mosses, ferns, and conifers. Basal angiosperms – mostly aquatic plants Unplaced in order, placed in Amborellaceae family • Amborella trichopoda – one of the most ancient flowering plants Unplaced in order, placed in Nymphaeaceae family • Water lily • Cabomba (fanwort) • Brasenia (watershield) Ceratophyllales • Hornwort Austrobaileyales • Illicium (anise tree, star anise) Basal angiosperms - magnoliids Canellales • Drimys (winter's bark) • Tasmanian pepper Laurales • Bay laurel • Cinnamon • Avocado • Sassafras • Camphor tree • Calycanthus (sweetshrub, spicebush) • Lindera (spicebush, Benjamin bush) Magnoliales • Custard-apple • Pawpaw • guanábana (soursop) • Sugar-apple or sweetsop • Cherimoya • Magnolia • Tuliptree • Michelia • Nutmeg • Clove Piperales • Black pepper • Kava • Lizard’s tail • Aristolochia (birthwort, pipevine, Dutchman's pipe) • Asarum (wild ginger) Basal angiosperms - monocots Acorales -

Butterflies and Moths of Dorchester County, Maryland, United States

Heliothis ononis Flax Bollworm Moth Coptotriche aenea Blackberry Leafminer Argyresthia canadensis Apyrrothrix araxes Dull Firetip Phocides pigmalion Mangrove Skipper Phocides belus Belus Skipper Phocides palemon Guava Skipper Phocides urania Urania skipper Proteides mercurius Mercurial Skipper Epargyreus zestos Zestos Skipper Epargyreus clarus Silver-spotted Skipper Epargyreus spanna Hispaniolan Silverdrop Epargyreus exadeus Broken Silverdrop Polygonus leo Hammock Skipper Polygonus savigny Manuel's Skipper Chioides albofasciatus White-striped Longtail Chioides zilpa Zilpa Longtail Chioides ixion Hispaniolan Longtail Aguna asander Gold-spotted Aguna Aguna claxon Emerald Aguna Aguna metophis Tailed Aguna Typhedanus undulatus Mottled Longtail Typhedanus ampyx Gold-tufted Skipper Polythrix octomaculata Eight-spotted Longtail Polythrix mexicanus Mexican Longtail Polythrix asine Asine Longtail Polythrix caunus (Herrich-Schäffer, 1869) Zestusa dorus Short-tailed Skipper Codatractus carlos Carlos' Mottled-Skipper Codatractus alcaeus White-crescent Longtail Codatractus yucatanus Yucatan Mottled-Skipper Codatractus arizonensis Arizona Skipper Codatractus valeriana Valeriana Skipper Urbanus proteus Long-tailed Skipper Urbanus viterboana Bluish Longtail Urbanus belli Double-striped Longtail Urbanus pronus Pronus Longtail Urbanus esmeraldus Esmeralda Longtail Urbanus evona Turquoise Longtail Urbanus dorantes Dorantes Longtail Urbanus teleus Teleus Longtail Urbanus tanna Tanna Longtail Urbanus simplicius Plain Longtail Urbanus procne Brown Longtail -

Shh/Gli Signaling in Anterior Pituitary

SHH/GLI SIGNALING IN ANTERIOR PITUITARY AND VENTRAL TELENCEPHALON DEVELOPMENT by YIWEI WANG Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Genetics CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY January, 2011 CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES We hereby approve the thesis/dissertation of _____________________________________________________ candidate for the ______________________degree *. (signed)_______________________________________________ (chair of the committee) ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ (date) _______________________ *We also certify that written approval has been obtained for any proprietary material contained therein. TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• i List of Figures ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• v List of Abbreviations •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• vii Acknowledgements •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• ix Abstract ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• x Chapter 1 Background and Significance ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 1 1.1 Introduction to the pituitary gland -

A Stylistic Approach to the God of Small Things Written by Arundhati Roy

Lingnan University Digital Commons @ Lingnan University Theses & Dissertations Department of English 2007 A stylistic approach to the God of Small Things written by Arundhati Roy Wing Yi, Monica CHAN Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.ln.edu.hk/eng_etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Chan, W. Y. M. (2007). A stylistic approach to the God of Small Things written by Arundhati Roy (Master's thesis, Lingnan University, Hong Kong). Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.14793/eng_etd.2 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of English at Digital Commons @ Lingnan University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Lingnan University. Terms of Use The copyright of this thesis is owned by its author. Any reproduction, adaptation, distribution or dissemination of this thesis without express authorization is strictly prohibited. All rights reserved. A STYLISTIC APPROACH TO THE GOD OF SMALL THINGS WRITTEN BY ARUNDHATI ROY CHAN WING YI MONICA MPHIL LINGNAN UNIVERSITY 2007 A STYLISTIC APPROACH TO THE GOD OF SMALL THINGS WRITTEN BY ARUNDHATI ROY by CHAN Wing Yi Monica A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Philosophy in English Lingnan University 2007 ABSTRACT A Stylistic Approach to The God of Small Things written by Arundhati Roy by CHAN Wing Yi Monica Master of Philosophy This thesis presents a creative-analytical hybrid production in relation to the stylistic distinctiveness in The God of Small Things, the debut novel of Arundhati Roy. -

Common Names Working-2008Jan

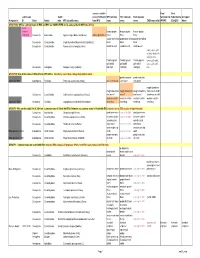

correct scientific Final Final submission Subfa name (if different WFI common ESC common ESA common Submitted to Submitted to Accepted Assigned to: ID Order Family mily WFI scientific name from WFI) name name name CABI name info? WFIWC: ESA/ESC: Name GROUP 000: Official common name in ESA and ESC are COMPLETED and is same as that in WFI (take off list) need change? bronze poplar bronze poplar bronze poplar 1026-Bup Coleoptera Buprestidae Agrilus liragus Barter and Brown Agrilus granulatus borer borer borer poplar-and-willow poplar-and-willow poplar-and-willow Coleoptera Curculionidae Cryptorhynchus [Sternochetus] lapathi (L.) borer borer borer Coleoptera Curculionidae Nemocestes incomptus (Horn) woods weevil woods weevil wood weevil cooley spruce gall adelgid; douglas fir adelges; sitka Cooley spruce Cooley spruce Cooley spruce spruce gall aphid; gall aphid gall aphid gall aphid spruce gall aphid, Homoptera Adelgidae Adelges cooleyi (Gillette) (adelgid) (adelgid) (adelgid) blue GROUP 00: One of the names in ESA, ESC or WFI differs (Decide by case; likely change highlighted name) ponderosa pine ponderosa pine approved 1989 Lepidoptera Pyralidae Dioryctria auranticella (Grote) pine coneworm coneworm coneworm rough strawberry rough strawberry rough strawberry rough strawberry root weevil; rough Coleoptera Curculionidae Otiorhynchus rugosostriatus (Goeze) root weevil weevil root weevil strawberry weevil western conifer western conifer- western conifer- western conifer- approved 1989 Hemiptera Coreidae Leptoglossus occidentalis Heidemann seed -

Pheromone-Based Disruption of Eucosma Sonomana and Rhyacionia Zozana (Lepidoptera: Tortricidae) Using Aerially Applied Microencapsulated Pheromone1

361 Pheromone-based disruption of Eucosma sonomana and Rhyacionia zozana (Lepidoptera: Tortricidae) using aerially applied microencapsulated pheromone1 Nancy E. Gillette, John D. Stein, Donald R. Owen, Jeffrey N. Webster, and Sylvia R. Mori Abstract: Two aerial applications of microencapsulated pheromone were conducted on five 20.2 ha plots to disrupt western pine shoot borer (Eucosma sonomana Kearfott) and ponderosa pine tip moth (Rhyacionia zozana (Kearfott); Lepidoptera: Tortricidae) orientation to pheromones and oviposition in ponderosa pine plantations in 2002 and 2004. The first application was made at 29.6 g active ingredient (AI)/ha, and the second at 59.3 g AI/ha. Baited sentinel traps were used to assess disruption of orientation by both moth species toward pheromones, and E. sonomana infes- tation levels were tallied from 2001 to 2004. Treatments disrupted orientation by both species for several weeks, with the first lasting 35 days and the second for 75 days. Both applications reduced infestation by E. sonomana,but the lower application rate provided greater absolute reduction, perhaps because prior infestation levels were higher in 2002 than in 2004. Infestations in treated plots were reduced by two-thirds in both years, suggesting that while increas- ing the application rate may prolong disruption, it may not provide greater proportional efficacy in terms of tree pro- tection. The incidence of infestations even in plots with complete disruption suggests that treatments missed some early emerging females or that mated females immigrated into treated plots; thus operational testing should be timed earlier in the season and should comprise much larger plots. In both years, moths emerged earlier than reported pre- viously, indicating that disruption programs should account for warmer climates in timing of applications. -

A Translation of the Linnaean Dissertation the Invisible World

BJHS 49(3): 353–382, September 2016. © British Society for the History of Science 2016 doi:10.1017/S0007087416000637 A translation of the Linnaean dissertation The Invisible World JANIS ANTONOVICS* AND JACOBUS KRITZINGER** Abstract. This study presents the first translation from Latin to English of the Linnaean disser- tation Mundus invisibilis or The Invisible World, submitted by Johannes Roos in 1769. The dissertation highlights Linnaeus’s conviction that infectious diseases could be transmitted by living organisms, too small to be seen. Biographies of Linnaeus often fail to mention that Linnaeus was correct in ascribing the cause of diseases such as measles, smallpox and syphilis to living organisms. The dissertation itself reviews the work of many microscopists, especially on zoophytes and insects, marvelling at the many unexpected discoveries. It then discusses and quotes at length the observations of Münchhausen suggesting that spores from fungi causing plant diseases germinate to produce animalcules, an observation that Linnaeus claimed to have confirmed. The dissertation then draws parallels between these findings and the conta- giousness of many human diseases, and urges further studies of this ‘invisible world’ since, as Roos avers, microscopic organisms may cause more destruction than occurs in all wars. Introduction Here we present the first translation from Latin to English of the Linnaean dissertation published in 1767 by Johannes Roos (1745–1828) entitled Dissertatio academica mundum invisibilem, breviter delineatura and republished by Carl Linnaeus (1707– 1778) several years later in the Amoenitates academicae under the title Mundus invisibi- lis or The Invisible World.1 Roos was a student of Linnaeus, and the dissertation is important in highlighting Linnaeus’s conviction that infectious diseases could be trans- mitted by living organisms.