“I Am One”: the Fragile/Assertive Self and Thematic Unity in The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Abai, Oracle of Apollo, 134 Achaia, 3Map; LH IIIC

INDEX Abai, oracle of Apollo, 134 Aghios Kosmas, 140 Achaia, 3map; LH IIIC pottery, 148; migration Aghios Minas (Drosia), 201 to northeast Aegean from, 188; nonpalatial Aghios Nikolaos (Vathy), 201 modes of political organization, 64n1, 112, Aghios Vasileios (Laconia), 3map, 9, 73n9, 243 120, 144; relations with Corinthian Gulf, 127; Agnanti, 158 “warrior burials”, 141. 144, 148, 188. See also agriculture, 18, 60, 207; access to resources, Ahhiyawa 61, 86, 88, 90, 101, 228; advent of iron Achaians, 110, 243 ploughshare, 171; Boeotia, 45–46; centralized Acharnai (Menidi), 55map, 66, 68map, 77map, consumption, 135; centralized production, 97–98, 104map, 238 73, 100, 113, 136; diffusion of, 245; East Lokris, Achinos, 197map, 203 49–50; Euboea, 52, 54, 209map; house-hold administration: absence of, 73, 141; as part of and community-based, 21, 135–36; intensified statehood, 66, 69, 71; center, 82; centralized, production, 70–71; large-scale (project), 121, 134, 238; complex offices for, 234; foreign, 64, 135; Lelantine Plain, 85, 207, 208–10; 107; Linear A, 9; Linear B, 9, 75–78, 84, nearest-neighbor analysis, 57; networks 94, 117–18; palatial, 27, 65, 69, 73–74, 105, of production, 101, 121; palatial control, 114; political, 63–64, 234–35; religious, 217; 10, 65, 69–70, 75, 81–83, 97, 207; Phokis, systems, 110, 113, 240; writing as technology 47; prehistoric Iron Age, 204–5, 242; for, 216–17 redistribution of products, 81, 101–2, 113, 135; Aegina, 9, 55map, 67, 99–100, 179, 219map subsistence, 73, 128, 190, 239; Thessaly 51, 70, Aeolians, 180, 187, 188 94–95; Thriasian Plain, 98 “age of heroes”, 151, 187, 200, 213, 222, 243, 260 agropastoral societies, 21, 26, 60, 84, 170 aggrandizement: competitive, 134; of the sea, 129; Ahhiyawa, 108–11 self-, 65, 66, 105, 147, 251 Aigai, 82 Aghia Elousa, 201 Aigaleo, Mt., 54, 55map, 96 Aghia Irini (Kea), 139map, 156, 197map, 199 Aigeira, 3map, 141 Aghia Marina Pyrgos, 77map, 81, 247 Akkadian, 105, 109, 255 Aghios Ilias, 85. -

Raquel Prado Romanillos1

Raquel Prado Romanillos1 "EVEN IF THEY CALL US CRAZY": A DE (DEVELOPMENT EDUCATION) EXPERIENCE BASED ON CLASSICAL LITERATURE TEXTS Abstract By means of this article I just want to share an experience on how to apply the global gaze (Education for Development, DE) to the daily routine of a Spanish Language and Literature class, based on an interdisciplinary project carried out together with the teachers of Mathematics and Biology of 3rd Grade ESO (Compulsory Secondary Education). The project addressed the values of environmental care and global citizenship. The starting point for Language and Literature class was the topic of the "locus amoenus", the myth of the four ages in Ovid's Metamorphoses, and fragments of Don Quixote of La Mancha. Key-words Literature, interdisciplinary project, environment, global citizens. 1 Raquel Prado Romanillos has worked as a Secondary Education teacher of Language and Literature since 1998. As a volunteer from a young age, she has taken part in development projects both in her hometown, Madrid (in toy and leisure libraries in areas of Vallecas), and abroad (neighbourhoods on the outskirts of Havana and in Sahrawi camps in Algeria). At present, her efforts are focused on her work as a teacher at María Reina de las Hijas de Jesús School, in the neighbourhood of Orcasur (Madrid), the educational project of which is, in itself, a community development project. Since 2012, she has coordinated the "Global Cities" project in the school, through which the way to introduce a more human and curriculum-committed perspective is beginning to gain ground and to be implemented. -

Macedonian Kings, Egyptian Pharaohs the Ptolemaic Family In

Department of World Cultures University of Helsinki Helsinki Macedonian Kings, Egyptian Pharaohs The Ptolemaic Family in the Encomiastic Poems of Callimachus Iiro Laukola ACADEMIC DISSERTATION To be publicly discussed, by due permission of the Faculty of Arts at the University of Helsinki in auditorium XV, University Main Building, on the 23rd of September, 2016 at 12 o’clock. Helsinki 2016 © Iiro Laukola 2016 ISBN 978-951-51-2383-1 (paperback.) ISBN 978-951-51-2384-8 (PDF) Unigrafia Helsinki 2016 Abstract The interaction between Greek and Egyptian cultural concepts has been an intense yet controversial topic in studies about Ptolemaic Egypt. The present study partakes in this discussion with an analysis of the encomiastic poems of Callimachus of Cyrene (c. 305 – c. 240 BC). The success of the Ptolemaic Dynasty is crystallized in the juxtaposing of the different roles of a Greek ǴdzȅǻǽǷȏȄ and of an Egyptian Pharaoh, and this study gives a glimpse of this political and ideological endeavour through the poetry of Callimachus. The contribution of the present work is to situate Callimachus in the core of the Ptolemaic court. Callimachus was a proponent of the Ptolemaic rule. By reappraising the traditional Greek beliefs, he examined the bicultural rule of the Ptolemies in his encomiastic poems. This work critically examines six Callimachean hymns, namely to Zeus, to Apollo, to Artemis, to Delos, to Athena and to Demeter together with the Victory of Berenice, the Lock of Berenice and the Ektheosis of Arsinoe. Characterized by ambiguous imagery, the hymns inspect the ruptures in Greek thought during the Hellenistic age. -

Archaic Eretria

ARCHAIC ERETRIA This book presents for the first time a history of Eretria during the Archaic Era, the city’s most notable period of political importance. Keith Walker examines all the major elements of the city’s success. One of the key factors explored is Eretria’s role as a pioneer coloniser in both the Levant and the West— its early Aegean ‘island empire’ anticipates that of Athens by more than a century, and Eretrian shipping and trade was similarly widespread. We are shown how the strength of the navy conferred thalassocratic status on the city between 506 and 490 BC, and that the importance of its rowers (Eretria means ‘the rowing city’) probably explains the appearance of its democratic constitution. Walker dates this to the last decade of the sixth century; given the presence of Athenian political exiles there, this may well have provided a model for the later reforms of Kleisthenes in Athens. Eretria’s major, indeed dominant, role in the events of central Greece in the last half of the sixth century, and in the events of the Ionian Revolt to 490, is clearly demonstrated, and the tyranny of Diagoras (c. 538–509), perhaps the golden age of the city, is fully examined. Full documentation of literary, epigraphic and archaeological sources (most of which have previously been inaccessible to an English-speaking audience) is provided, creating a fascinating history and a valuable resource for the Greek historian. Keith Walker is a Research Associate in the Department of Classics, History and Religion at the University of New England, Armidale, Australia. -

Apollon Issue

Apollon The Journal of Psychological Astrology The Sun-god And The Astrological Sun - Liz Greene Creativity, Spontaneity, Independence: Three Children Of The Devil - Adolf Guggenbühl-Craig Whom Doth The Grail Serve? - Anne Whitaker Fire And The Imagination - Darby Costello Leonard Cohen’s "Secret Chart" - John Etherington Issue 1 October 1998 £6 Apollo with the ecliptic worn as a sash. This figure is from the 2nd half of the 5th century BCE, and is now at the Vatican Museum. Figleaf courtesy of the Vatican. Photo: E. Greene Cover Picture The Chariot of Apollo Odilon Redon ©Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam “The French symbolist artist Odilon Redon, b. April 20th 1840, d. July 6th 1916, isolated by frail health and parental indifference at an early age, peopled his loneliness with imaginary beings, as he was later to people his works” Joan Siegfried, Grolier Multimedia Encyclopedia Apollon The Journal of Psychological Astrology Published by: Contents The Centre for Psychological Astrology BCM Box 1815 Editorial 4 London WC1N 3XX This Creativity Lark England Dermod Moore Tel/Fax: +44-181-749 2330 www.astrologer.com/cpa The Sun-god and the Astrological Sun 6 The Mythology and Psychology of Apollo Directors: Dr Liz Greene Liz Greene Charles Harvey Admin: Juliet Sharman-Burke Creativity, Spontaneity, Independence: 16 Distributed by: Three Children of the Devil John Etherington Adolf Guggenbühl-Craig Midheaven Bookshop 396 Caledonian Road The Sun in the Tarot and the Horoscope 24 London N1 1DN Juliet Sharman-Burke England Tel: +44-171-607 4133 Whom -

TRADITIONAL POETRY and the ANNALES of QUINTUS ENNIUS John Francis Fisher A

REINVENTING EPIC: TRADITIONAL POETRY AND THE ANNALES OF QUINTUS ENNIUS John Francis Fisher A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE FACULTY OF PRINCETON UNIVERSITY IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY RECOMMENDED FOR ACCEPTANCE BY THE DEPARTMENT OF CLASSICS SEPTEMBER 2006 UMI Number: 3223832 UMI Microform 3223832 Copyright 2006 by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest Information and Learning Company 300 North Zeeb Road P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, MI 48106-1346 © Copyright by John Francis Fisher, 2006. All rights reserved. ii Reinventing Epic: Traditional Poetry and the Annales of Quintus Ennius John Francis Fisher Abstract The present scholarship views the Annales of Quintus Ennius as a hybrid of the Latin Saturnian and Greek hexameter traditions. This configuration overlooks the influence of a larger and older tradition of Italic verbal art which manifests itself in documents such as the prayers preserved in Cato’s De agricultura in Latin, the Iguvine Tables in Umbrian, and documents in other Italic languages including Oscan and South Picene. These documents are marked by three salient features: alliterative doubling figures, figurae etymologicae, and a pool of traditional phraseology which may be traced back to Proto-Italic, the reconstructed ancestor of the Italic languages. A close examination of the fragments of the Annales reveals that all three of these markers of Italic verbal art are integral parts of the diction the poem. Ennius famously remarked that he possessed three hearts, one Latin, one Greek and one Oscan, which the second century writer Aulus Gellius understands as ability to speak three languages. -

Select Epigrams from the Greek Anthology

SELECT EPIGRAMS FROM THE GREEK ANTHOLOGY J. W. MACKAIL∗ Fellow of Balliol College, Oxford. PREPARER’S NOTE This book was published in 1890 by Longmans, Green, and Co., London; and New York: 15 East 16th Street. The epigrams in the book are given both in Greek and in English. This text includes only the English. Where Greek is present in short citations, it has been given here in transliterated form and marked with brackets. A chapter of Notes on the translations has also been omitted. eti pou proima leuxoia Meleager in /Anth. Pal./ iv. 1. Dim now and soil’d, Like the soil’d tissue of white violets Left, freshly gather’d, on their native bank. M. Arnold, /Sohrab and Rustum/. PREFACE The purpose of this book is to present a complete collection, subject to certain definitions and exceptions which will be mentioned later, of all the best extant Greek Epigrams. Although many epigrams not given here have in different ways a special interest of their own, none, it is hoped, have been excluded which are of the first excellence in any style. But, while it would be easy to agree on three-fourths of the matter to be included in such a scope, perhaps hardly any two persons would be in exact accordance with regard to the rest; with many pieces which lie on the border line of excellence, the decision must be made on a balance of very slight considerations, and becomes in the end one rather of personal taste than of any fixed principle. For the Greek Anthology proper, use has chiefly been made of the two ∗PDF created by pdfbooks.co.za 1 great works of Jacobs, -

Poetic Diction, Poetic Discourse and the Poetic Register

proceedings of the British Academy, 93.21-93 Poetic Diction, Poetic Discourse and the Poetic Register R. G. G. COLEMAN Summary. A number of distinctive characteristics can be iden- tified in the language used by Latin poets. To start with the lexicon, most of the words commonly cited as instances of poetic diction - ensis; fessus, meare, de, -que. -que etc. - are demonstrably archaic, having been displaced in the prose register. Archaic too are certain grammatical forms found in poetry - e.g. auldi, gen. pl. superum, agier, conticuere - and syntactic constructions like the use of simple cases for pre- I.positional phrases and of infinitives instead of the clausal structures of classical prose. Poets in all languages exploit the linguistic resources of past as well as present, but this facility is especially prominent where, as in Latin, the genre traditions positively encouraged imitatio. Some of the syntactic character- istics are influenced wholly or partly by Greek, as are other ingredients of the poetic register. The classical quantitative metres, derived from Greek, dictated the rhythmic pattern of the Latin words. Greek loan words and especially proper names - Chaoniae, Corydon, Pyrrha, Tempe, Theseus, Zephym etc. -brought exotic tones to the aural texture, often enhanced by Greek case forms. They also brought an allusive richness to their contexts. However, the most impressive charac- teristics after the metre were not dependent on foreign intrusion: the creation of imagery, often as an essential feature of a poetic argument, and the tropes of semantic transfer - metaphor, metonymy, synecdoche - were frequently deployed through common words. In fact no words were too prosaic to appear in even the highest poetic contexts, always assuming their metricality. -

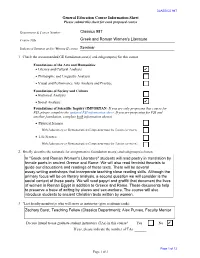

CLASSICS 98T General Education Course Information Sheet Please Submit This Sheet for Each Proposed Course

CLASSICS 98T General Education Course Information Sheet Please submit this sheet for each proposed course Department & Course Number Course Title Indicate if Seminar and/or Writing II course 1 Check the recommended GE foundation area(s) and subgroups(s) for this course Foundations of the Arts and Humanities ñ Literary and Cultural Analysis ñ Philosophic and Linguistic Analysis ñ Visual and Performance Arts Analysis and Practice Foundations of Society and Culture ñ Historical Analysis ñ Social Analysis Foundations of Scientific Inquiry (IMPORTAN: If you are only proposing this course for FSI, please complete the updated FSI information sheet. If you are proposing for FSI and another foundation, complete both information sheets) ñ Physical Science With Laboratory or Demonstration Component must be 5 units (or more) ñ Life Science With Laboratory or Demonstration Component must be 5 units (or more) 2. Briefly describe the rationale for assignment to foundation area(s) and subgroup(s) chosen. 3. "List faculty member(s) who will serve as instructor (give academic rank): Do you intend to use graduate student instructors (TAs) in this course? Yes No If yes, please indicate the number of TAs Page 1 of 12 Page 1 of 3 CLASSICS 98T 4. Indicate when do you anticipate teaching this course over the next three years: 2018-19 Fall Winter Spring Enrollment Enrollment Enrollment 2019-20 Fall Winter Spring Enrollment Enrollment Enrollment 2020-21 Fall Winter Spring Enrollment Enrollment Enrollment 5. GE Course Units Is this an existing course that has been modified for inclusion in the new GE? Yes No If yes, provide a brief explanation of what has changed: Present Number of Units: Proposed Number of Units: 6. -

And Troop Beverly Hills

‘CHRISTMAS IN MONTANA’ Cast Bios KELLIE MARTIN (Sara) – While Kellie Martin has garnered many acting credits, she is probably still most fondly remembered for her work as Becca Thatcher in the popular ABC series “Life Goes On,” for which she received an Emmy® nomination for Best Supporting Actress. From there, Martin played the title role in the CBS drama “Christy,” as well as medical student Lucy Knight on NBC’s “ER” from 1998-2000. Martin broke ground as Army Captain Nicole Galassini on “Army Wives,” and appeared in the quirky TBS comedy “The Guest Book.” Most recently, she starred in Lifetime’s “Death of a Cheerleader.” She has starred as fan-favorite sleuth Hailey Dean in the “Hailey Dean Mysteries” franchise, which is in its ninth installment. Martin also serves as executive producer on the popular Hallmark Movies & Mysteries “Emma Fielding Mysteries” franchise. Other recent television projects include starring roles in the Hallmark Channel Original Movies “So You Said Yes,” “The Christmas Ornament,” “I Married Who?” and “Smooch;” starring roles in the Hallmark Movies & Mysteries Originals “Hello, It’s Me” and “Hailey Dean Mysteries: Killer Sentence;” and guest-starring roles on ABC’s “Private Practice” and “Grey’s Anatomy,” Lifetime’s “Drop Dead Diva” and AMC’s “Mad Men.” Martin’s feature film credits include Open House, Malibu’s Most Wanted, A Goofy Movie, Matinee and Troop Beverly Hills. In 1999, Martin took on a new role as national spokesperson for the American Autoimmune Related Diseases Association (AARDA). Drawing on her family’s experience (her sister Heather passed away at age 19 from complications following a misdiagnosed case of lupus), Martin works to raise awareness of autoimmune disease as a major women’s health issue. -

1 4 Henry Stead Swinish Classics

Pre-print version of chapter 4 in Stead & Hall eds. (2015) Greek and Roman Classics and the British Struggle for Social Reform (Bloomsbury). 4 Henry Stead Swinish classics; or a conservative clash with Cockney culture On 1 November 1790 Edmund Burke’s Reflections on the Revolution in France was published in England. The counter-revolutionary intervention of a Whig politician who had previously championed numerous progressive causes provided an important rallying point for traditionalist thinkers by expressing in plain language their concerns 1 Pre-print version of chapter 4 in Stead & Hall eds. (2015) Greek and Roman Classics and the British Struggle for Social Reform (Bloomsbury). about the social upheaval across the channel. From the viewpoint of pro- revolutionaries, Burke’s Reflections gave shape to the conservative forces they were up against; its publication provoked a ‘pamphlet war’, which included such key radical responses to the Reflections as Mary Wollstonecraft’s A Vindication of the Rights of Man (1790) and Tom Paine’s The Rights of Man (1791).1 In Burke’s treatise, he expressed a concern for the fate of French civilisation and its culture, and in so doing coined a term that would haunt his counter-revolutionary campaign. Capping his deliberation about what would happen to French civilisation following the overthrow of its nobility and clergy, which he viewed as the twin guardians of European culture, he wrote, ‘learning will be cast into the mire, and trodden down under the hoofs of a swinish multitude’. This chapter asks what part the Greek and Roman classics played in the cultural war between British reformists and conservatives in the periodical press of the late 1810s and early 1820s. -

4. Barsine, Daughter of Artabazus

Alexander’s Lovers by Andrew Chugg 4. Barsine, Daughter of Artabazus Barsine was by birth a minor princess of the Achaemenid Empire of the Persians, for her father, Artabazus, was the son of a Great King’s daughter.197 It is known that his father was Pharnabazus, who had married Apame, the daughter of Artaxerxes II, some time between 392 - 387BC.198 Artabazus was a senior Persian Satrap and courtier and was latterly renowned for his loyalty first to Darius, then to Alexander. Perhaps this was the outcome of a bad experience of the consequences of disloyalty earlier in his long career. In 358BC Artaxerxes III Ochus had upon his accession ordered the western Satraps to disband their mercenary armies, but this edict had eventually edged Artabazus into an unsuccessful revolt. He spent some years in exile at Philip’s court during Alexander’s childhood, starting in about 352BC and extending until around 349BC,199 at which time he became reconciled with the Great King. It is likely that his daughter Barsine and the rest of his immediate family accompanied him in his exile, so it is feasible that Barsine knew Alexander when they were both still children. Plutarch relates that she had received a “Greek upbringing”, though in point of fact this education could just as well have been delivered in Artabazus’ Satrapy of Hellespontine Phrygia, where the population was predominantly ethnically Greek. As a young girl, Barsine appears to have married Mentor,200 a Greek mercenary general from Rhodes. Artabazus had previously married the sister of this Rhodian, so Barsine may have been Mentor’s niece.