Church and Society: the Value of Perichoresis in Understanding Ubuntu with Special Reference to John Zizioulas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thinking Through Matters of Faith

THINKING THROUGH MATTERS OF FAITH “Born of the Virgin Mary”: Toward a Sprachregelung on a Delicate Point of Doctrine his essay offers an interpretation of the traditional Catholic teach- Ting that “Jesus Christ, conceived by the power of the Holy Spirit, was born of the Virgin Mary.” It will be attempted to do so in such a way as to positively acknowledge three blocks of non-theological knowledge: (1) the critical difference between tacit, unspoken mean- ing-elements in speech and the invisible, unwritten meaning-elements discoverable in texts; (2) the account of the anatomical and physiolog- ical “facts” involved in human fertilization and conception as they were widely understood in the classical and medieval periods, and thus, presumably, at the place and time of the composition of the infancy narratives in the gospels of Matthew and Luke, and (3) the modern, scientific account of these same “facts,” now generally understood and accepted. Indirectly, the contrasts treated in (1) and between (2) and (3) will raise issues in the field of the hermeneutics of Christian doctrine. For all this, the author’s chief purpose in writing is systematic- theological, but in such a way as to emphasize linguistic, and hence, pastoral elements as well. After all, the accepted, shared language of faith must never be totally severed from the live speech of the people professing it, and silence is a strangely telling part of live speech. Happily, the Great Tradition’s constant teaching on this point is now being studied in many places. Unhappily, some of the scrutiny, often allegedly academic, is mixed with scorn; still, scrutinizing (as against doubting) Christian doctrine is the birthright of Christians; if they do not take advantage of this privilege, non-Christians will. -

Shiatu in Arabic)—Eventually Came to Be Called Shia (Often Spelled Shiite in English Sources)

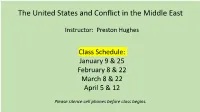

The United States and Conflict in the Middle East Instructor: Preston Hughes Class Schedule: January 9 & 25 February 8 & 22 March 8 & 22 April 5 & 12 Please silence cell phones before class begins. The US and Conflict in the Middle East Setting the Stage HITTITE EMPIRE circa 1600 BC – 1178 BC Shown in Blue is Hittite Empire circa 1300 BC The first written international treaty known to humankind, Kadesh, was made between Egyptian Pharaoh Ramesses II and Hittite King Hattushili, in 1269 BCE. The tablet is now displayed at the Istanbul Archeological Museum, where you can also find the oldest love poem, written by the Sumerian queen to the Sumerian king in 2037-2039 BCE. The museum also houses the Alexander Sarcophagus. Assyrian Empire circa 7th century BCE (greatest extent) Babylonia Tomb of Cyrus the Great, founder of the Achaemenid Empire (the first Persian Empire) in the 6th century BCE The Persian Empire circa 500 BCE Empire of Alexander the Great 4th century BCE Post Alexander Armenian Empire Armenia its greatest extent under Tigranes the Great, 69 BC (including vassals) Kurds Roman Empire At its greatest extent (vassals in pink) Roman Empire Sassanid Empire The Sasanian Empire at its greatest extent c. 620 CE, under Khosrow II . Greatest temporary extent during Byzantine – Sasanian War of 602-628 shown in stripes. Next Slide: Islamic Empire For Byzantine Slide discuss who lives in Byzantine Empire, Christian heretics, conditions under which they live just prior to birth of Muhammad The Qur’an on the Qur’an We sent to you [Muhammad] the Scripture with the truth, confirming the Scriptures that came before it, and with final authority over them: so judge between them according to what God has sent down. -

Xi Colloquium Anatolicum

COLLOQUIUM ANATOLICUM XI 2012 INSTITUTUM TURCICUM SCIENTIAE ANTIQUITATIS TÜRK ESKİÇAĞ BİLİMLERİ ENSTİTÜSÜ COLLOQUIUM ANATOLICUM ANADOLU SOHBETLERİ XI 2012 INSTITUTUM TURCICUM SCIENTIAE ANTIQUITATIS TÜRK ESKİÇAĞ BİLİMLERİ ENSTİTÜSÜ COLLOQUIUM ANATOLICUM ANADOLU SOHBETLERİ XI ISSN 1303-8486 COLLOQUIUM ANATOLICUM dergisi, TÜBİTAK-ULAKBİM Sosyal Bilimler Veri Tabanında taranmaktadır. COLLOQUIUM ANATOLICUM dergisi hakemli bir dergi olup, yılda bir kez yayınlanmaktadır. © 2012 Türk Eskiçağ Bilimleri Enstitüsü Her hakkı mahfuzdur. Bu yayının hiçbir bölümü kopya edilemez. Dipnot vermeden alıntı yapılamaz ve izin alınmadan elektronik, mekanik, fotokopi vb. yollarla kopya edilip yayınlanamaz. Editörler/Editors Metin Alparslan Ali Akkaya Baskı / Printing MAS Matbaacılık A.Ş. Hamidiye Mah. Soğuksu Cad. No. 3 Kağıthane - İstanbul Tel: +90 (212) 294 10 00 Fax: +90 (212) 294 90 80 Sertifika No: 12055 Yapım ve Dağıtım/Production and Distribution Zero Prodüksiyon Kitap-Yayın-Dağıtım Ltd. Şti. Tel: +90 (212) 244 7521 Fax: +90 (212) 244 3209 [email protected] www.zerobooksonline.com TÜRK ESKİÇAĞ BİLİMLERİ ENSTİTÜSÜ İstiklal Cad. No. 181 Merkez Han Kat: 2 34433 Beyoğlu-İstanbul Tel: + 90 (212) 292 0963 / + 90 (212) 514 0397 [email protected] www.turkinst.org TÜRK ESKİÇAĞ BİLİMLERİ ENSTİTÜSÜ Uluslararası Akademiler Birliği Muhabir Üyesi Corresponding Member of the International Union of Academies ENST‹TÜMÜZÜN KURUCUSU VE BAfiKANI PROF. DR. AL‹ D‹NÇOL’UN AZ‹Z HATIRASINA IN PERPETUAM MEMORIAM CONDITORIS PRAESIDISQUE INSTITUTI NOSTRI PROF. DR. AL‹ D‹NÇOL -

Heritage at Risk

H @ R 2008 –2010 ICOMOS W ICOMOS HERITAGE O RLD RLD AT RISK R EP O RT 2008RT –2010 –2010 HER ICOMOS WORLD REPORT 2008–2010 I TAGE AT AT TAGE ON MONUMENTS AND SITES IN DANGER Ris K INTERNATIONAL COUNciL ON MONUMENTS AND SiTES CONSEIL INTERNATIONAL DES MONUMENTS ET DES SiTES CONSEJO INTERNAciONAL DE MONUMENTOS Y SiTIOS мЕждународный совЕт по вопросам памятников и достопримЕчатЕльных мЕст HERITAGE AT RISK Patrimoine en Péril / Patrimonio en Peligro ICOMOS WORLD REPORT 2008–2010 ON MONUMENTS AND SITES IN DANGER ICOMOS rapport mondial 2008–2010 sur des monuments et des sites en péril ICOMOS informe mundial 2008–2010 sobre monumentos y sitios en peligro edited by Christoph Machat, Michael Petzet and John Ziesemer Published by hendrik Bäßler verlag · berlin Heritage at Risk edited by ICOMOS PRESIDENT: Gustavo Araoz SECRETARY GENERAL: Bénédicte Selfslagh TREASURER GENERAL: Philippe La Hausse de Lalouvière VICE PRESIDENTS: Kristal Buckley, Alfredo Conti, Guo Zhan Andrew Hall, Wilfried Lipp OFFICE: International Secretariat of ICOMOS 49 –51 rue de la Fédération, 75015 Paris – France Funded by the Federal Government Commissioner for Cultural Affairs and the Media upon a Decision of the German Bundestag EDITORIAL WORK: Christoph Machat, Michael Petzet, John Ziesemer The texts provided for this publication reflect the independent view of each committee and /or the different authors. Photo credits can be found in the captions, otherwise the pictures were provided by the various committees, authors or individual members of ICOMOS. Front and Back Covers: Cambodia, Temple of Preah Vihear (photo: Michael Petzet) Inside Front Cover: Pakistan, Upper Indus Valley, Buddha under the Tree of Enlightenment, Rock Art at Risk (photo: Harald Hauptmann) Inside Back Cover: Georgia, Tower house in Revaz Khojelani ( photo: Christoph Machat) © 2010 ICOMOS – published by hendrik Bäßler verlag · berlin ISBN 978-3-930388-65-3 CONTENTS Foreword by Francesco Bandarin, Assistant Director-General for Culture, UNESCO, Paris .................................. -

Pilgrimage, Spatial Interaction, and Memory at Three Marian Sites

University of Denver Digital Commons @ DU Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 1-1-2016 Pilgrimage, Spatial Interaction, and Memory at Three Marian Sites Katherine Rousseau University of Denver Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd Part of the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons, and the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Rousseau, Katherine, "Pilgrimage, Spatial Interaction, and Memory at Three Marian Sites" (2016). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 1129. https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd/1129 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at Digital Commons @ DU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ DU. For more information, please contact [email protected],[email protected]. Pilgrimage, Spatial Interaction, and Memory at Three Marian Sites __________ A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the University of Denver and the Iliff School of Theology Joint PhD Program University of Denver __________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy __________ by T.K. Rousseau June 2016 Advisor: Scott Montgomery ©Copyright by T.K. Rousseau 2016 All Rights Reserved Author: T.K. Rousseau Title: Pilgrimage, Spatial Interaction, and Memory at Three Marian Sites Advisor: Scott Montgomery Degree Date: June 2016 Abstract Global mediation, communication, and technology facilitate pilgrimage places with porous boundaries, and the dynamics of porousness are complex and varied. Three Marian, Catholic pilgrimage places demonstrate the potential for variation in porous boundaries: Chartres cathedral; the Marian apparition location of Medjugorje; and the House of the Virgin Mary near Ephesus. -

Islamist Populism and Civilizationism in the Friday Sermons of Turkey’S Diyanet

religions Article Religion in Creating Populist Appeal: Islamist Populism and Civilizationism in the Friday Sermons of Turkey’s Diyanet Ihsan Yilmaz 1,* , Mustafa Demir 2 and Nicholas Morieson 3 1 Alfred Deakin Institute for Citizenship and Globalization, Deakin University, Melbourne, VIC 3215, Australia 2 European Center for Populism Studies, 1050 Brussels, Belgium; [email protected] 3 The Institute for Religion, Politics and Society, Australian Catholic University, Melbourne, VIC 3065, Australia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Drawing on the extant literature on populism, we aim to flesh out how populists in power utilize religion and related state resources in setting up aggressive, multidimensional religious pop- ulist “us” versus “them” binaries. We focus on Turkey as our case and argue that by instrumentalizing the Diyanet (Turkey’s Presidency of Religious Affairs), the authoritarian Islamists in power have been able to consolidate manufactured populist dichotomies via the Diyanet’s weekly Friday sermons. Populists’ control and use of a state institution to propagate populist civilizationist narratives and construct antagonistic binaries are underexamined in the literature. Therefore, by examining Turkish populists’ use of the Diyanet, this paper will make a general contribution to the extant literature on religion and populism. Furthermore, by analyzing the Diyanet’s weekly Friday sermons from the last ten years we demonstrate how different aspects of populism—its horizontal, vertical, and civilizational dimensions—have become embedded in the Diyanet’s Friday sermons. Equally, this paper shows how these sermons have been tailored to facilitate the populist appeal of Erdo˘gan’s Islamist regime. Through the Friday sermons, the majority—Sunni Muslim Turks are presented with Citation: Yilmaz, Ihsan, Mustafa Demir, and Nicholas Morieson. -

Gregory of Nyssa : the Letters / Introduction, Translation, and Commentary by Anna M

Gregory of Nyssa: The Letters Supplements to Vigiliae Christianae Formerly Philosophia Patrum Editors J. den Boeft – J. van Oort – W. L. Petersen – D. T. Runia – J. C. M. van Winden – C. Scholten VOLUME 83 CHAPTERTWO Gregory of Nyssa: The Letters Introduction, Translation and Commentary by Anna M. Silvas LEIDEN • BOSTON 2007 This book is printed on acid-free paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Gregory, of Nyssa, Saint, ca. 335-ca.394. [Correspondence. English] Gregory of Nyssa : the letters / introduction, translation, and commentary by Anna M. Silvas. p. cm. — (Supplements to Vigiliae Christianae, ISSN 0920-623X ; v. 83) Includes bibliographical references (p. ) and index. ISBN-13: 978-90-04-15290-8 ISBN-10: 90-04-15290-3 (hardback : alk. paper) 1. Gregory, of Nyssa, Saint, ca. 335-ca. 394—Correspondence. 2. Christian saints—Turkey—Correspondence. I. Silvas, Anna. II. Title. III. Letters. BR65.G74E5 2007 270.2092—dc22 2006049279 ISSN 0920-623x ISBN-13: 978 90 04 15290 8 ISBN-10: 90 04 15290 3 © Copyright 2007 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill, Hotei Publishing, IDC Publishers, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers and VSP. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by Brill provided that the appropriate fees are paid directly to The Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Suite 910, Danvers, MA 01923, USA. -

T. C. Çevre Ve Orman Bakanliği Özel Çevre Koruma Kurumu Başkanliği

T. C. ÇEVRE VE ORMAN BAKANLIĞI ÖZEL ÇEVRE KORUMA KURUMU BAŞKANLIĞI IHLARA ÖZEL ÇEVRE KORUMA BÖLGESİ SOSYO - EKONOMİK, TARİHİ VE KÜLTÜREL DEĞERLER ARAŞTIRMASI KESİN RAPOR T.C. ÇEVRE VE ORMAN BAKANLIĞI Proje Sahibinin Adı ÖZEL ÇEVRE KORUMA KURUMU BAŞKANLIĞI Alparslan Türkeş Caddesi Adresi 31. Sokak 10 No’ lu Hizmet Binası 06510 Beştepe / Yenimahalle - Ankara Telefon : 0 (312) 222 12 34 Telefon ve Faks Numaraları Faks : 0 (312) 222 26 61 Ihlara Özel Çevre Koruma Bölgesi Projenin Adı Sosyo - Ekonomik, Tarihi ve Kültürel Değerlerin Araştırılması Projesi Projenin Yeri Ihlara Özel Çevre Koruma Bölgesi Raporu Hazırlayan Kuruluşun Optimar Danışmanlık Tanıtım Araştırma ve Adı Organizasyon A.Ş. Adresi Olgunlar Sk. No: 11/17 Bakanlıklar / Çankaya - Ankara Telefon : 0 (312) 417 56 76 Telefon ve Faks Numarası Fax : 0 (312) 417 29 26 Rapor Sunum Tarihi 20/12/2010 II Proje Yürütücüsü Doç. Dr. Nilay Çabuk KAYA (Sosyolog) Proje Ekibi Dr. Mehmet AYSOY Proje Yürütücü Asistanı (Sosyolog) Doç. Dr. Emre MADRAN (Mimar) Yrd. Doç. Dr. Nihan Özdemir SÖNMEZ (Şehir ve Bölge Plancısı) Doç. Dr. Adil BİNAL (Hidrojeolog) Doç. Dr. M. Sacit PEKAK (Bizans Tarihi) Dr. Nida NAYCI (Mimar) Esra KARATAŞ (Şehir Plancısı- CBS Uzmanı) Anketörler Abdullah GÜNAY ( Sosyolog) Ahmet Tarık GÜVEN (İletişim Mezunu) Mustafa Emre NAKIŞ (İstatistikci) Şuayb Garani EKİCİ(Çalışma Ekonomisti) Burcu ATAV (İngilizce Öğretmeni) Abdullah AKÜNAL (İstatistikci) Doğan KÜÇÜKBALABAN (Sosyolog) Özel Çevre Koruma Kurumu Başkanlığı Proje Ekibi Kurum Başkanı: Ahmet ÖZYANIK Daire Başkanı: Mehmet MENENGİÇ Şube Müdürü: Sücaattin BARAN Kontrol Teşkilatı Üyesi: Hatice ÜNCÜ, Mimar Kontrol Teşkilatı Üyesi: Levent KESKİN, Şehir Plancısı Kontrol Teşkilatı Üyesi: Muhsine MISIRLIOĞLU, Kimya Mühendisi Kontrol Teşkilatı Üyesi: Reyhan ÖZDEMİR, Çevre Mühendisi III İÇİNDEKİLER BİRİNCİ BÖLÜM 1 GİRİŞ ..................................................................................................................................... -

Anāhitā: Transformations of an Iranian Goddess Inauguraldissertation Zur

Anāhitā: Transformations of an Iranian Goddess Inauguraldissertation zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades eines Doktors der Philosophie dem Fachbereich Geschichts- und Kulturwissenschaften der Freien Universität Berlin vorgelegt von Manya Saadi-nejad 2019 First Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Maria Macuch Second Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Almut Hintze Date of defense: 15 April 2019 ii Table of Contents Acknowledgements vii A Note on Transcriptions viii Abbreviations ix Introduction 1 Chapter One: Scholarly Studies on Anāhitā 10 1.1 The Yašts and “monotheism” 13 1.1.1 The Ābān Yašt 14 1.2 Anāhitā’s Roots 15 1.3 Anāhitā’s Name and Epithets 20 1.4 Anāhitā’s description 23 Chapter Two: The Primary Sources 31 2.1 The Textual Sources in Iranian Languages: Avestan Texts 33 2.1.1 The Yasna 34 2.1.2 The Yašts 35 2.1.3 The Hāδōxt Nask 37 2.2 Middle Persian Sources 37 2.2.1 The Bundahišn 38 2.2.2 The Dēnkard 39 2.2.3 The Wizīdagīhā-ī Zādspram 40 2.2.4 The Zand ī Wahman Yasn 41 2.2.5 The Dādestān ī Mēnog ī Xrad 42 2.2.6 The Ardā Wīrāz nāmag 42 2.2.7 The Abadīh ud sahīgīh ī Sag(k)istān 43 2.2.8 The Ayādgār ī Wuzurg-mihr 43 2.3 Old and Middle Persian Inscriptions and Iconography 44 2.4 The Greco-Roman Texts 45 2.5 Vedic sources 46 2.6 Mesopotamian sources 47 2.7 Archaeological Sources 49 2.7.1 Indo-European Archeological Sites 49 2.7.2 Archaeological Sites in Iran 50 2.7.2.1 Anāhitā’s Temples 51 2.8 Sources from the Islamic Period 52 2.8.1 The Šāh-nāmeh (“Book of Kings”) 52 2.8.2 Other Sources from the Islamic Period 54 2.8.3 Oral and Folk Traditions 55 2.9 Problems -

Robert Ousterhout

Fig. 1. Kızıl Kilise at Sivrihisar, distant view, from the east (author) THE RED CHURCH AT SİVRIHİSAR (CAPPADOCIA): ASPECTS OF STRUCTURE AND CONSTRUCTION Robert Ousterhout The Red Church (or Kızıl Kilise) at Sivrihisar has been known to scholars since the beginning of the 20th century.1 Situated in a high mountain valley above Karbala (Gelveri or Güzelyurt) in western Cappadocia, the distinctive red stone, quarried locally, gives the popular name to the church (Figs. 1-2). Long associated with Gregory of Nazianzos and his estate at Arianzos, the building actually dates from the sixth century – more than a century after his death. It was known to the 19th-century Greeks of the area as St. Panteleimon – that 1 F. Hild and M. Restle, Kappadokien, Tabula Imperii Byzantini 2 (Vienna, 1981), 150-51; H. Rott, 1 is, not associated with Gregory, whose relics were elsewhere. Nevertheless, the Red Church is usually discussed as an example of a memorial church, allegedly containing his tomb. Oddly, beyond generalized discussions of morphology, the architectural features of the surviving building have received considerably less attention than its supposed origin or function.2 The best preserved of the Byzantine masonry churches of central Anatolia, the Red Church is unique in the survival of its dome – perhaps the earliest surviving example of a dome rising above a tall, windowed drum. In the following short paper, I will examine the structural system of the building focusing on the unique solutions developed by its masons to address the outward thrusts of the dome and barrel vaults. I will also touch upon several unusual details of design and construction preserved in the building’s fabric. -

Bektashism in Albania: Political History of a Religious Movement Albert Doja

Bektashism in Albania: Political history of a Religious Movement Albert Doja To cite this version: Albert Doja. Bektashism in Albania: Political history of a Religious Movement. AIIS Press, pp.104, 2008, 978-99943-742-8-1. halshs-01382774 HAL Id: halshs-01382774 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-01382774 Submitted on 20 Oct 2016 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. ALBERT DOJA "Member of the Academy of Sciences" BEKTASHISM IN ALBANIA POLITICAL HISTORY OF A RELIGIOUS MOVEMENT Ilii) Tirana, 2008 AlbertDoja BEKTASHISM IN ALBANIA: POLITlCALHISTORYOFARELIGIOUSMOVEMENT ISBN 978-99943-742-8-1 First published in: Totalitorian Movements and Politica/ Religions, vol. 7 (1). 2006, pp. 83-107. (ISSN: 1469-0764, eiSSN: 1743-9647, URL http:l/dx.doi.org/ 10.1080/ 146907605004 77919). Copyright 2006 Q Routledge Taylors & Francis. Reprint witb permission of T.aylors & Francis Ltd., London. Albert Doja, e1ected in 2008 a full ordinary Member of the Albanian Academy of Sciences, is Professor of Sociology & Antbropology at the University of New York and European University of Tirana; Honorary Researcb Fellow at the Departmenl of Anthropology, University College London; and has been on secondment to the United Nations Developmeot Programme under the Brain Gain Initiative as the Deputy Rector of the University of Durres in Albania. -

Gregory of Nazianzus' Soteriological Pneumatology

Studien und Texte zu Antike und Christentum Studies and Texts in Antiquity and Christianity Herausgeber /Editors Christoph Markschies (Berlin) · Martin Wallraff (München) Christian Wildberg (Pittsburgh) Beirat /Advisory Board Peter Brown (Princeton) · Susanna Elm (Berkeley) Johannes Hahn (Münster) · Emanuela Prinzivalli (Rom) Jörg Rüpke (Erfurt) 117 Oliver B. Langworthy Gregory of Nazianzus’ Soteriological Pneumatology Mohr Siebeck Oliver B. Langworthy , born 1988; 2010 MTheol (Hons); 2012 MLitt; 2016 PhD in Historical Theology from the University of St Andrews; since 2017 Associate Lecturer in the School of Di - vinity at the University of St Andrews. orcid.org/0000-0002-9382-0600 ISBN 978-3-16-158951-5 / eISBN 978-3-16-158952-2 DOI 10.1628 / 978-3-16-158952-2 ISSN 1436-3003 / eISSN 2568-7433 (Studien und Texte zu Antike und Christentum) The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliogra - phie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de . © 2019 Mohr Siebeck Tübingen, Germany. www.mohrsiebeck.com This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, in any form (beyond that permitted by copyright law) without the publisher’s written permission. This applies particularly to reproduc - tions, translations and storage and processing in electronic systems. The book was printed on non-aging paper by Laupp & Göbel in Gomaringen and bound by Buchbinderei Nädele in Nehren. Printed in Germany. Preface This book argues that soteriological operation of the Holy Spirit, or soterio- logical pneumatology, of Gregory of Nazianzus is a coherent, essential, but underexamined area of his thought. Gregory’s soteriological pneumatology is surprisingly absent from scholarship, particularly in light of a resurgent inter- est in pneumatology, and in Gregory’s use of θέωσις.