Classical Chinese Poetry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Characteristics of Chinese Poetic-Musical Creations

Characteristics of Chinese Poetic-Musical Creations Yan GENG1 Abstract: The present study intoduces a series of characteristics related to Chinese poetry. It shows that, together with rhythmical structure and intonation (which has a crucial role in conveying meaning), an additional, fundamental aspect of Chinese poetry lies in the latent, pictorial effect of the writing. Various genres and forms of Chinese poetry are touched upon, as well as a series of figures of speech, themes (nature, love, sadness, mythology etc.) and symbols (particularly of vegetal and animal origin), which are frequently encountered in the poems. Key-words: rhythm, intonation, system of tones, rhyme, system of writing, figures of speech 1. Introduction In his Advanced Music Theory course, &RQVWDQWLQ 5kSă VKRZV WKDW ³we can differentiate between two levels of the phenomenon of rhythm: the first, a general philosophical one, meaning, within the context of music, the ensemble of movements perceived, thus the macrostructural level; the second, the micro-VWUXFWXUH ZKHUH UK\WKP PHDQV GXUDWLRQV « LQWHQVLWLHVDQGWHPSR « 0RUHRYHUZHFDQVD\WKDWUK\WKPGRHVQRWH[LVWEXWUDWKHUMXVW the succession of sounds in time [does].´2 Studies on rhythm, carried out by ethno- musicology researchers, can guide us to its genesis. A first fact that these studies point towards is the indissoluble unity of the birth process of artistic creation: poetry, music (rhythm-melody) and dance, which manifested syncretically for a very lengthy period of time. These aspects are not singular or characteristic for just one culture, as it appears that they have manifested everywhere from the very beginning of mankind. There is proof both in Chinese culture, as well as in ancient Romanian culture, that certifies the existence of a syncretic development of the arts and language. -

The Web That Has No Weaver

THE WEB THAT HAS NO WEAVER Understanding Chinese Medicine “The Web That Has No Weaver opens the great door of understanding to the profoundness of Chinese medicine.” —People’s Daily, Beijing, China “The Web That Has No Weaver with its manifold merits … is a successful introduction to Chinese medicine. We recommend it to our colleagues in China.” —Chinese Journal of Integrated Traditional and Chinese Medicine, Beijing, China “Ted Kaptchuk’s book [has] something for practically everyone . Kaptchuk, himself an extraordinary combination of elements, is a thinker whose writing is more accessible than that of Joseph Needham or Manfred Porkert with no less scholarship. There is more here to think about, chew over, ponder or reflect upon than you are liable to find elsewhere. This may sound like a rave review: it is.” —Journal of Traditional Acupuncture “The Web That Has No Weaver is an encyclopedia of how to tell from the Eastern perspective ‘what is wrong.’” —Larry Dossey, author of Space, Time, and Medicine “Valuable as a compendium of traditional Chinese medical doctrine.” —Joseph Needham, author of Science and Civilization in China “The only approximation for authenticity is The Barefoot Doctor’s Manual, and this will take readers much further.” —The Kirkus Reviews “Kaptchuk has become a lyricist for the art of healing. And the more he tells us about traditional Chinese medicine, the more clearly we see the link between philosophy, art, and the physician’s craft.” —Houston Chronicle “Ted Kaptchuk’s book was inspirational in the development of my acupuncture practice and gave me a deep understanding of traditional Chinese medicine. -

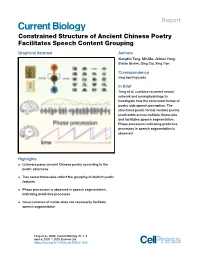

Constrained Structure of Ancient Chinese Poetry Facilitates Speech Content Grouping

Report Constrained Structure of Ancient Chinese Poetry Facilitates Speech Content Grouping Graphical Abstract Authors Xiangbin Teng, Min Ma, Jinbiao Yang, Stefan Blohm, Qing Cai, Xing Tian Correspondence [email protected] In Brief Teng et al. combine recurrent neural network and neurophysiology to investigate how the structured format of poetry aids speech perception. The structured poetic format renders poems predictable across multiple timescales and facilitates speech segmentation. Phase precession indicating predictive processes in speech segmentation is observed. Highlights d Listeners parse ancient Chinese poetry according to the poetic structures d Two neural timescales reflect the grouping of distinct poetic features d Phase precession is observed in speech segmentation, indicating predictive processes d Co-occurrence of words does not necessarily facilitate speech segmentation Teng et al., 2020, Current Biology 30, 1–7 April 6, 2020 ª 2020 Elsevier Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2020.01.059 Please cite this article in press as: Teng et al., Constrained Structure of Ancient Chinese Poetry Facilitates Speech Content Grouping, Current Biology (2020), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2020.01.059 Current Biology Report Constrained Structure of Ancient Chinese Poetry Facilitates Speech Content Grouping Xiangbin Teng,1,8 Min Ma,2,8 Jinbiao Yang,3,4,5,6 Stefan Blohm,1 Qing Cai,4,7 and Xing Tian3,4,7,9,* 1Department of Neuroscience, Max Planck Institute for Empirical Aesthetics, Frankfurt 60322, Germany 2Google Inc., 111 8th Avenue, New -

Mirror, Moon, and Memory in Eighth-Century China: from Dragon Pond to Lunar Palace

EUGENE Y. WANG Mirror, Moon, and Memory in Eighth-Century China: From Dragon Pond to Lunar Palace Why the Flight-to-the-Moon The Bard’s one-time felicitous phrasing of a shrewd observation has by now fossilized into a commonplace: that one may “hold, as ’twere, the mirror up to nature; to show virtue her own feature, scorn her own image, and the very age and body of the time his form and pressure.”1 Likewise deeply rooted in Chinese discourse, the same analogy has endured since antiquity.2 As a commonplace, it is true and does not merit renewed attention. When presented with a physical mirror from the past that does register its time, however, we realize that the mirroring or showing promised by such a wisdom is not something we can take for granted. The mirror does not show its time, at least not in a straightforward way. It in fact veils, disfi gures, and ultimately sublimates the historical reality it purports to refl ect. A case in point is the scene on an eighth-century Chinese mirror (fi g. 1). It shows, at the bottom, a dragon strutting or prancing over a pond. A pair of birds, each holding a knot of ribbon in its beak, fl ies toward a small sphere at the top. Inside the circle is a tree fl anked by a hare on the left and a toad on the right. So, what is the design all about? A quick iconographic exposition seems to be in order. To begin, the small sphere refers to the moon. -

The Reception and Translation of Classical Chinese Poetry in English

NCUE Journal of Humanities Vol. 6, pp. 47-64 September, 2012 The Reception and Translation of Classical Chinese Poetry in English Chia-hui Liao∗ Abstract Translation and reception are inseparable. Translation helps disseminate foreign literature in the target system. An evident example is Ezra Pound’s translation based on the 8th-century Chinese poet Li Bo’s “The River-Merchant’s Wife,” which has been anthologised in Anglophone literature. Through a diachronic survey of the translation of classical Chinese poetry in English, the current paper places emphasis on the interaction between the translation and the target socio-cultural context. It attempts to stress that translation occurs in a context—a translated work is not autonomous and isolated from the literary, cultural, social, and political activities of the receiving end. Keywords: poetry translation, context, reception, target system, publishing phenomenon ∗ Adjunct Lecturer, Department of English, National Changhua University of Education. Received December 30, 2011; accepted March 21, 2012; last revised May 13, 2012. 47 國立彰化師範大學文學院學報 第六期,頁 47-64 二○一二年九月 中詩英譯與接受現象 廖佳慧∗ 摘要 研究翻譯作品,必得研究其在譯入環境中的接受反應。透過翻譯,外國文學在 目的系統中廣宣流布。龐德的〈河商之妻〉(譯寫自李白的〈長干行〉)即一代表實 例,至今仍被納入英美文學選集中。藉由中詩英譯的歷時調查,本文側重譯作與譯 入文境間的互動,審視前者與後者的社會文化間的關係。本文強調翻譯行為的發生 與接受一方的時代背景相互作用。譯作不會憑空出現,亦不會在目的環境中形成封 閉的狀態,而是與文學、文化、社會與政治等活動彼此交流、影響。 關鍵字:詩詞翻譯、文境、接受反應、目的/譯入系統、出版現象 ∗ 國立彰化師範大學英語系兼任講師。 到稿日期:2011 年 12 月 30 日;確定刊登日期:2012 年 3 月 21 日;最後修訂日期:2012 年 5 月 13 日。 48 The Reception and Translation of Classical Chinese Poetry in English Writing does not happen in a vacuum, it happens in a context and the process of translating texts form one cultural system into another is not a neutral, innocent, transparent activity. -

Mirror, Death, and Rhetoric: Reading Later Han Chinese Bronze Artifacts Author(S): Eugene Yuejin Wang Source: the Art Bulletin, Vol

Mirror, Death, and Rhetoric: Reading Later Han Chinese Bronze Artifacts Author(s): Eugene Yuejin Wang Source: The Art Bulletin, Vol. 76, No. 3, (Sep., 1994), pp. 511-534 Published by: College Art Association Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3046042 Accessed: 17/04/2008 11:17 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=caa. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit organization founded in 1995 to build trusted digital archives for scholarship. We enable the scholarly community to preserve their work and the materials they rely upon, and to build a common research platform that promotes the discovery and use of these resources. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. http://www.jstor.org Mirror, Death, and Rhetoric: Reading Later Han Chinese Bronze Artifacts Eugene Yuejin Wang a 1 Jian (looking/mirror), stages of development of ancient ideograph (adapted from Zhongwendazzdian [Encyclopedic dictionary of the Chinese language], Taipei, 1982, vi, 9853) History as Mirror: Trope and Artifact people. -

An Explanation of Gexing

Front. Lit. Stud. China 2010, 4(3): 442–461 DOI 10.1007/s11702-010-0107-5 RESEARCH ARTICLE XUE Tianwei, WANG Quan An Explanation of Gexing © Higher Education Press and Springer-Verlag 2010 Abstract Gexing 歌行 is a historical and robust prosodic style that flourished (not originated) in the Tang dynasty. Since ancient times, the understanding of the prosody of gexing has remained in debate, which focuses on the relationship between gexing and yuefu 乐府 (collection of ballad songs of the music bureau). The points-of-view held by all sides can be summarized as a “grand gexing” perspective (defining gexing in a broad sense) and four major “small gexing” perspectives (defining gexing in a narrow sense). The former is namely what Hu Yinglin 胡应麟 from Ming dynasty said, “gexing is a general term for seven-character ancient poems.” The first “small gexing” perspective distinguishes gexing from guti yuefu 古体乐府 (tradition yuefu); the second distinguishes it from xinti yuefu 新体乐府 (new yuefu poems with non-conventional themes); the third takes “the lyric title” as the requisite condition of gexing; and the fourth perspective adopts the criterion of “metricality” in distinguishing gexing from ancient poems. The “grand gexing” perspective is the only one that is able to reveal the core prosodic features of gexing and give specification to the intension and extension of gexing as a prosodic style. Keywords gexing, prosody, grand gexing, seven-character ancient poems Received January 25, 2010 XUE Tianwei ( ) College of Humanities, Xinjiang Normal University, Urumuqi 830054, China E-mail: [email protected] WANG Quan International School, University of International Business and Economics, Beijing 100029, China E-mail: [email protected] An Explanation of Gexing 443 The “Grand Gexing” Perspective and “Small Gexing” Perspective Gexing, namely the seven-character (both unified seven-character lines and mixed lines containing seven character ones) gexing, occupies an equal position with rhythm poems in Tang dynasty and even after that in the poetic world. -

The Contrast of Chinese and English in the Translation of Chinese Poetry

Asian Social Science December, 2008 The Contrast of Chinese and English in the Translation of Chinese Poetry Ning Li Continuing Education College Beijing Information Science & Technology University Beijing 100076, China E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Chinese poetry is the soul of Chinese literature and Chinese culture. A good translation of a Chinese verse can promote the prevalence of Chinese culture. In the translation of Chinese poetry, translators should not only keep the characteristics of Chinese poems, but also embody the English characteristics. This article analyzed some versions of translation and proposed factors affecting the translation of Chinese poetry. Keywords: Chinese Poetry, Translation, Contrast 1. Introduction Chinese poetry is one of the most important parts in Chinese literature. Since The Book of Odes, the first poetry collection written by Confucius in the spring-autumn period was known by people, Chinese poetry has developed quickly. In the Tang Dynasty, Chinese poetry was at its peak. In this period, many immortal poems were written and had great influence on the later Dynasties. In the later Dynasties, Chinese poetry went on its development. But because of the development of other literary styles—Yuan Songs (drama created mainly in Yuan Dynasty), novels, and essays, poetry is no longer the major literary style. In this article, I’d like to talk about the contrast of Chinese and English in the translation of Tang-poems. Tang-poems has very strict phonological format. In each stanza, there are five (in quatrains) or seven (in regulated verses) words. Using limited words to express unlimited sense is the major characteristic of Chinese poetry. -

Foundation for Chinese Performing Arts 中華表演藝術基金會

中華表演藝術基金會 FOUNDATION FOR CHINESE PERFORMING ARTS [email protected] www.ChinesePerformingArts.net The Foundation for Chinese Performing Arts, is a non-profit organization registered in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts in January, 1989. The main objectives of the Foundation are: * To enhance the understanding and the appreciation of Eastern heritage through music and performing arts. * To promote Chinese music and performing arts through performances. * To provide opportunities and assistance to young Asian artists. The Founder and the President is Dr. Catherine Tan Chan 譚嘉陵. AWARDS AND SCHOLARSHIPS The Foundation held its official opening ceremony on September 23, 1989, at the Rivers School in Weston. Professor Chou Wen-Chung of Columbia University lectured on the late Alexander Tcherepnin and his contribution in promoting Chinese music. The Tcherepnin Society, represented by the late Madame Ming Tcherepnin, an Honorable Board Member of the Foundation, donated to the Harvard Yenching Library a set of original musical manuscripts composed by Alexander Tcherepnin and his student, Chiang Wen-Yeh. Dr. Eugene Wu, Director of the Harvard Yenching Library, was there to receive the gift that includes the original orchestra score of the National Anthem of the Republic of China commissioned in 1937 to Alexander Tcherepnin by the Chinese government. The Foundation awarded Ms. Wha Kyung Byun as the outstanding music educator. In early December 1989, the Foundation, recognized Professor Sylvia Shue-Tee Lee for her contribution in educating young violinists. The recipients of the Foundation's artist scholarship award were: 1989 Jindong Cai 蔡金冬, MM conductor ,New England Conservatory, NEC (currently conductor and Associate Professor of Music, Stanford University,) 1990: (late) Pei-Kun Xi, MM, conductor, NEC; 1991: pianists John Park and J.G. -

REVISED DRAFT for Entertext

EnterText 5.3 J. GILL HOLLAND Teaching Narrative in the Five-Character Quatrain of Li Po 1 The pattern of complication and resolution within the traditional five-character quatrain (chüeh-chü, jueju) of “Ancient Style poetry” (ku-shih, gushi) of Li Po (Li Bo, Li Bai; 701-762) goes a long way toward explaining Burton Watson’s high praise of Li Po’s poetry: “It is generally agreed that [Li Po] and Tu Fu raised poetry in the shih form to its highest level of power and expressiveness.”1 To his friend Tu Fu, Li Po left the “compact and highly schematized form of Regulated Verse” (lü-shih, lushi), which was deemed the ideal poetic form in the High T’ang of the eighth century.2 Before we begin, we must distinguish between Ancient Style poetry, which Li Po wrote, and the more celebrated Regulated Verse. The purpose of this essay is to explain the art of Li Po’s quatrain in a way that will do justice to the subtlety of the former yet avoid the enormous complexities of the latter.3 The strict rules dictating patterns of tones, parallelism and caesuras of Regulated Verse are not the subject of our attention here. A thousand years after Li Po wrote, eight of his twenty-nine poems selected for the T’ang-shih san-pai-shou (Three Hundred Poems of the T’ang Dynasty, 1763/1764), J. Gill Holland: The Five-Character Quatrain of Li Po 133 EnterText 5.3 the most famous anthology of T’ang poetry, are in the five-character quatrain form.4 Today even in translation the twenty-character story of the quatrain can be felt deeply. -

UC Santa Barbara UC Santa Barbara Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Santa Barbara UC Santa Barbara Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Fashioning the Reclusive Persona: Zeng Jing's Informal Portraits of the Jiangnan Literati Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/2mx8m4wt Author Choi, Seokwon Publication Date 2016 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Santa Barbara Fashioning the Reclusive Persona: Zeng Jing’s Informal Portraits of the Jiangnan Literati A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Art History by Seokwon Choi Committee in charge: Professor Peter C. Sturman, Chair Professor Miriam Wattles Professor Hui-shu Lee December 2016 The dissertation of Seokwon Choi is approved. _____________________________________________ Miriam Wattles _____________________________________________ Hui-shu Lee _____________________________________________ Peter C. Sturman, Committee Chair September 2016 Fashioning the Reclusive Persona: Zeng Jing’s Informal Portraits of the Jiangnan Literati Copyright © 2016 by Seokwon Choi iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My sincerest gratitude goes to my advisor, Professor Peter C. Sturman, whose guidance, patience, and confidence in me have made my doctoral journey not only possible but also enjoyable. It is thanks to him that I was able to transcend the difficulties of academic work and find pleasure in reading, writing, painting, and calligraphy. As a role model, Professor Sturman taught me how to be an artful recluse like the Jiangnan literati. I am also greatly appreciative for the encouragement and counsel of Professor Hui-shu Lee. Without her valuable suggestions from its earliest stage, this project would never have taken shape. I would like to express appreciation to Professor Miriam Wattles for insightful comments and thought-provoking discussions that helped me to consider the issues of portraiture in a broader East Asian context. -

How Poetry Became Meditation in Late-Ninth-Century China

how poetry became meditation Asia Major (2019) 3d ser. Vol. 32.2: 113-151 thomas j. mazanec How Poetry Became Meditation in Late-Ninth-Century China abstract: In late-ninth-century China, poetry and meditation became equated — not just meta- phorically, but as two equally valid means of achieving stillness and insight. This article discusses how several strands in literary and Buddhist discourses fed into an assertion about such a unity by the poet-monk Qiji 齊己 (864–937?). One strand was the aesthetic of kuyin 苦吟 (“bitter intoning”), which involved intense devotion to poetry to the point of suffering. At stake too was the poet as “fashioner” — one who helps make and shape a microcosm that mirrors the impersonal natural forces of the macrocosm. Jia Dao 賈島 (779–843) was crucial in popularizing this sense of kuyin. Concurrently, an older layer of the literary-theoretical tradition, which saw the poet’s spirit as roaming the cosmos, was also given new life in late Tang and mixed with kuyin and Buddhist meditation. This led to the assertion that poetry and meditation were two gates to the same goal, with Qiji and others turning poetry writing into the pursuit of enlightenment. keywords: Buddhism, meditation, poetry, Tang dynasty ometime in the early-tenth century, not long after the great Tang S dynasty 唐 (618–907) collapsed and the land fell under the control of regional strongmen, a Buddhist monk named Qichan 棲蟾 wrote a poem to another monk. The first line reads: “Poetry is meditation for Confucians 詩為儒者禪.”1 The line makes a curious claim: the practice Thomas Mazanec, Dept.