Reconstructing Public Utility Networks: a Program for Action

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

July 2016 Full Board Minutes

THE CITY OF NEW YORK MANHATTAN COMMUNITY BOARD 3 59 East 4th Street - New York, NY 10003 Phone (212) 533- 5300 - Fax (212) 533- 3659 www.cb3manhattan.org - [email protected] Jamie Rogers, Board Chair Susan Stetzer, District Manager July 2016 Full Board Minutes Meeting of Community Board 3 held on Tuesday, July 26, 2016 at 6:30pm at Cooper Union Rose Auditorium, 41 Cooper Square. Public Session: Robyn Shapiro, The Lowline: Reported that EDC announced conditional designation of the underground trolley terminal for use by The Lowline. Lowline launching young ambassadors program. Lowline is hiring a coordinator for the program. Application is online. Hope Provost, resident of 14th Street: supported CB3's Land Use committee decision to deny the variance request for 435 East 14th. Martha Adams Sullivan: Gouverneur Health Center, spoke on the services Gouverneur provides, upcoming events and the upgrades after its major renovation. 2nd Annual Open House Sat Nov 12. Mary Habstritt, Lilac Preservation Project: announced visit of historic ships to Pier 36 from Sept 9 – 19. Open to tour for free. Vaylateena Jones, LES Power Partnership: Asking CB3 to support literacy program DYCD Compass and DOE Universal 2nd Requesting 3rd Street Men's Shelter to come speak to CB3 Asking CB3 to support Health and Hospital Corp and Bellevue now before its too late. Adrienne Platch, resident of 14th Street: supported the Land Use Committee's decision to deny the variance at 435 East 14th Street. Urges the full board to do the same. Agnes Warnielista: supported the Land Use Committee's decision to deny the variance at 435 East 14th Street. -

An Economic Development Plan for the City of Ithaca a Program for Action

AN ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT PLAN FOR THE CITY OF ITHACA A PROGRAM FOR ACTION Prepared for the City ofIthaca by: PLANNINGIENVIRONMENTAL RESEARCH CONSULTANTS 31 0 West State Street Ithaca, NY 14850 With the assistance ofthe City ofIthaca Planning and Development staff September 1998 (Accepted by Common Council March 5, 2003) Economic Development Plan City ofIthaca, New York Alan J. Cohen - Mayor With special thanks to members ofthe Economic Development Plan Advisory Committee: David Sprague - Chairperson, Sprague & Janowsky, Ithaca, N.Y. I Martha Armstrong - Tompkins County Area Development, Ithaca, N.Y. Barbara Blanchard -Tompkins County Board ofRepresentatives, Ithaca, N.Y. I Susan Blumenthal- Common Council, City ofIthaca Scott Dagenais - M & T Bank, Ithaca, N.Y. I David Kay - Planning and Development Board, City ofIthaca Bill Myers - Alternatives Federal Credit Union, Ithaca, N.Y. I Tom Niederkorn -PlanninglEnvironmental Research Consultants, Ithaca, N.Y. John Novarr - Novarr-Mackesey Development Company, Ithaca, NY I Megan Shay - Evaporated Metals Films (EMF), Ithaca, N.Y. Martin Violette - Conservation Advisory Council, City ofIthaca _I Cal Walker - Assistant Director in the Learning Strategies Center, Ithaca, NY H. Matthys Van Cort - Director ofPlanning & Development, City ofIthaca I) Jeannie Lee - Economic Development Planner, City ofIthaca Consultant: I Tom Niederkorn -Planning/Environmental Research Consultants, Ithaca, N.Y. I Other Staff: Jennifer Kusznir - Economic Development Planner, City ofIthaca I Douglas McDonald - Director ofEconomic Development, City ofIthaca I I I I -I AN ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT PLAN FOR THE CITY OF ITHACA A PROGRAM FOR ACTION TABLE OF CONTENTS Section 1. INTRODUCTION Part I 1 Part II 6 Section 2. IDGHLIGHTS 8 Section 3. CONDITIONS AND TRENDS 11 I Section 4. -

2015-2016 JACL PROGRAM for ACTION Introduction the Program

2015-2016 JACL PROGRAM FOR ACTION Introduction The Program for Action sets the operational and program priorities for the JACL in each biennium. The ongoing effectiveness of the organization will be determined by the successful outcomes of these important initiatives. Vision As a national civil rights organization, JACL strives to secure equal treatment and social justice for all. Mission The Japanese American Citizens League is a national organization whose mission is to secure and safeguard the civil and human rights of Asian and Pacific Islander (AAPI) and all communities who are affected by injustice and bigotry. The leaders and members of the JACL also work to promote and preserve the heritage and legacy of the Japanese American Community. SOCIAL JUSTICE Goal: To build and support grassroots mobilizations and policy reforms for Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders (AAPI) at the national, state, and local levels that ensure the full attainment of civil liberties and equal access to the social, political and economic resources in our society. Objectives: 1. Advocate to expand civil rights protections and equal opportunity for all AAPIs while monitoring and addressing incidents of bias and discrimination that infringe the rights and limit the opportunities of AAPIs. 2. Continue to strengthen our institutional relationships with public officials, policy makers, civil rights organizations, and community leaders on the national, state, and local levels in order to collaborate more effectively on various civil liberties issues; and by encouraging AAPIs to run for public office. 3. Work to eradicate negative stereotyping of AAPIs by the media in all its forms including print, radio, television, film, advertising, etc. -

The Case of the Second Avenue Subway Performing Organization: the City College of New York, CUNY

front cover page.ai 1 8/20/2014 9:55:30 AM University Transportation Research Center - Region 2 Final Report The Politics of Large Infrastructure Investment Decision-Making: The Case of the Second Avenue Subway Performing Organization: The City College of New York, CUNY November 2013 Sponsor: University Transportation Research Center - Region 2 University Transportation Research Center - Region 2 UTRC-RF Project No: 49111-16-23 The Region 2 University Transportation Research Center (UTRC) is one of ten original University Transportation Centers established in 1987 by the U.S. Congress. These Centers were established Project Date: November 2013 with the recognition that transportation plays a key role in the nation's economy and the quality of life of its citizens. University faculty members provide a critical link in resolving our national and regional transportation problems while training the professionals who address our transpor- Project Title: The Politics of Large Infrastructure Invest- tation systems and their customers on a daily basis. ment Decision-Making: The Case of the Second Avenue Subway The UTRC was established in order to support research, education and the transfer of technology in the ield of transportation. The theme of the Center is "Planning and Managing Regional Project’s Website: Transportation Systems in a Changing World." Presently, under the direction of Dr. Camille Kamga, http://www.utrc2.org/research/projects/transportation- the UTRC represents USDOT Region II, including New York, New Jersey, Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands. Functioning as a consortium of twelve major Universities throughout the region, mega-project-case-ny-2nd-ave-subway UTRC is located at the CUNY Institute for Transportation Systems at The City College of New York, the lead institution of the consortium. -

National Program for Action to Raise Effectiveness of the Protection of Human Rights and Freedoms in the Republic of Azerbaijan

National Program for Action to Raise Effectiveness of the Protection of Human Rights and Freedoms in the Republic of Azerbaijan The National Activity Program is being approved with the aim of raising effectiveness of protection of human rights and freedoms, promoting legal culture and ensuring sustainability of activities to improve the regulatory and legal framework and the human rights protection system. Chapter I Improvement of the regulatory and legal framework 1.1. Drafting laws of the Republic of Azerbaijan relying upon the principal criterion of human rights and freedoms secured in the Constitution of the Republic of Azerbaijan and the international treaties to which Azerbaijan is a signatory. Article 12 of the Constitution of the Republic of Azerbaijan provides that ensuring the rights and freedoms of individual and citizen and a decent standard of living for citizens of the Republic of Azerbaijan is the supreme goal of the State. To achieve this goal, it is necessary to ensure that the laws adopted in the Republic of Azerbaijan primarily secure the rights and freedoms enshrined by the Constitution of the Republic of Azerbaijan and the international treaties to which the Republic of Azerbaijan is a signatory. Current legislative practice in the country shows that in preparation of laws the legislature is guided by the Constitution of the Republic of Azerbaijan and the international treaties to which the Republic of Azerbaijan is a signatory. Apart from this, many draft laws are being submitted, for expertise, to international organizations specializing in human rights and subsequently adopted with due account taken of their recommendations. -

The League of Women Voters of Atlanta-Fulton County 1182 W

SEPTEMBER 1974 CALENDAR Aug. 20 9:30 AM - Unit Leader’s Workshop, LWV office Aug. 21 Last day for Primary nominees to file notice of candidacy Aug. 23 9 AM-10 PM Atlanta Public Hearings — Who Controls American Education? National Committee for Citizens in Educa tion - Atlanta City Hall Aug. 24 11 AM - 1:30 PM - Meet the Candidates The League of Women Voters Luncheon meeting and forum - sponsored by the Georgia Council on Crime and Delin- quency. Responses to questions on crime, delinquency and improving criminal justice of Atlanta-Fulton County system in Georgia. Lunch 12:15 - $5. 00. At the Riviera Hyatt House. Aug. 24 10 AM - Democratic Party Convention to elect delegates to Congressional District 1182 W Peachtree St NE - 209 Convention (on Sept. 7) which will send dele- gates to a Policy Conference in Kansas City (December 6-8). Atlanta, Ga 30309 873-2044 District Place 34th Kathleen Mitchell Elementary School 2480 Paul D. West Dr., College Park President - Mrs. Daniel Ehrlich 35th Russell High School Editor - Mrs. Walter Haun 1500 Jefferson Ave., East Point Asst. Ed. - Mrs. R. J. Fisher, Jr. 36 th Joseph B. Whitehead Boys Club THOUGHT FOR THE MONTH~ 1900 Lakewood Ave., Atlanta "The end of government is tho good of 37th Morningside Elem. School mankind.. .and which is best for man 1053 E. Rock Springs Rd., Atlanta kind, that the people should be always 38th Harper High School exposed to the boundless will of tyranny, Corner of Collier and Fairburn, Atlanta or that the rulers should be sometimes 39th liable to be opposed when they grow ex Student Union Bldg., Morris Brown College horbitant in their power, and employ it 643 Hunter Street, Atlanta for the destruction and not the preser 40th E. -

Innovation in Public Transportation

W Co'" Sf*rts o* A DIRECTORY OF RESEARCH, DEVELOPMENT AND DEMONSTRATION PROJECTS Fiscal Year 1975 U.S. Department of Transportation Urban Mass Transportation Administration Washington, D.C. 20590 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C. 20402 - Price $1.80 Stock No. 050-014-00006-1 Introduction This annual publication contains descriptions of through contracts with private firms, or through tion Act of 1964, as amended. The principal current research, development and demonstration working agreements with other Federal depart- method of reporting is through annual publication (RD&D) projects sponsored and funded by the ments and agencies. UMTA generally initiates of the compilation of reports on the status of U.S. Department of Transportation's Urban Mass and plans these RD&D projects and performs individual projects. Transportation Administration (UMTA). analytical tasks as well. The volume dated June 30, 1972 constituted an These projects are conducted under the author- Research projects are intended to produce infor- historical record of all projects funded under the ity of Section 6(a) of the Urban Mass Transporta- mation about possible improvements in urban Act to that point as well as projects funded tion Act of 1964, as amended (78 Stat. 302, 49 mass transportation. The products of research earlier under authorization of the Housing Act of U.S.C. 1601 et. seq.). This statute authorizes the projects are reports or studies. 1961. This volume is available from the National Secretary of Transportation "to undertake re- Technical Information Service (NTIS), access num- Development projects involve fabrication, testing, search, development, and demonstration projects ber PB-2 13-228. -

Science the Endless Frontier Science the Endless Frontier

1/28/2019 Science the Endless Frontier Science The Endless Frontier A Report to the President by Vannevar Bush, Director of the Office of Scientific Research and Development, July 1945 (United States Government Printing Office, Washington: 1945) TABLE OF CONTENTS Letter of Transmittal President Roosevelt's Letter Summary of the Report 1. Introduction: Scientific Progress is Essential Science is a Proper Concern of Government Government Relations to Science - Past and Future Freedom of Inquiry Must be Preserved 2. The War Against Disease: In War In Peace Unsolved Problems Broad and Basic Studies Needed Coordinated Attack on Special Problems Action is Necessary 3. Science and the Public Welfare: Relation to National Security Science and Jobs The Importance of Basic Research Centers of Basic Research Research Within the Government Industrial Research International Exchange of Scientific Information The Special Need for Federal Support The Cost of a Program 4. Renewal of our Scientific Talent: Nature of the Problem A Note of Warning The Wartime Deficit Improve the Quality Remove the Barriers The Generation in Uniform Must Not be Lost A Program 5. A Problem of Scientific Reconversion: Effects of Mobilization of Science for War Security Restrictions Should be Lifted Promptly Need for Coordination A Board to Control Release Publication Should be Encouraged 6. The Means to the End: New Responsibilities for Government The Mechanism Five Fundamentals Military Research https://www.nsf.gov/od/lpa/nsf50/vbush1945.htm 1/30 1/28/2019 Science the Endless Frontier National Research Foundation I. Purposes II. Members III. Organizations IV. Functions V. Patent Policy VI. Special Authority VII. -

Accelerating Electric Bus Adoption in the New York Mta Bus System

EVery City ACCELERATING ELECTRIC BUS ADOPTION IN THE NEW YORK MTA BUS SYSTEM A project of the Energy and Environment Practicum Columbia University – School of International and Public Affairs Andrew Catania, Lauren Kastner, Eugene Tseng, and Michael Woods MAY, 2019 INTRODUCTION This paper examines the Metropolitan Transit Authority’s (MTA) goal to transition its 5700-vehicle bus fleet from internal combustion engines (ICE) to a battery electric bus (BEB) fleet by the year 2040. This transition will bring two direct benefits: improved local air quality for New Yorkers and reduced greenhouse gas emissions from the New York City transportation sector. Electric Bus Background Key challenges faced by the MTA, Con Edison and New York City in their deployment | Page 3 Metropolitan Transit Authority Governance structure, existing bus fleet, and initial test pilot of electric buses | Page 3 Stakeholder Overview Various groups involved MTA’s transition to electric buses | Page 6 Emission and Pollution Reduction Goals Public policy and regulations implemented by New York State, New York City aimed at reducing greenhouse gas emissions and reducing pollution | Page 9 Model City – London Case Study Case study of London’s experience with electric buses | Page 10 Funding Background on the MTA’s funding and total cost of ownership of electric buses | Page 15 Grid Constraints Considerations for electric vehicle rate design and charging costs | Page 19 Operational Considerations Examines strategies for electric bus implementation and scale up | Page 22 Recommendations Policy recommendations for the MTA and related stakeholders | Page 25 Reflections Lessons learned from NYC that can be applied to every city and identifies additional research needs. -

(Mostly) True Story of Helvetica and the New York City Subway by Paul Shaw November 18, 2008

FROM VOICE ~ TOPICS: branding/identity, history, signage, typography The (Mostly) True Story of Helvetica and the New York City Subway by Paul Shaw November 18, 2008 here is a commonly held belief that Helvetica is the signage typeface of the New York City subway system, a belief reinforced by Helvetica, Gary Hustwit’s popular 2007 documentary T about the typeface. But it is not true—or rather, it is only somewhat true. Helvetica is the official typeface of the MTA today, but it was not the typeface specified by Unimark International when it created a new signage system at the end of the 1960s. Why was Helvetica not chosen originally? What was chosen in its place? Why is Helvetica used now, and when did the changeover occur? To answer those questions this essay explores several important histories: of the New York City subway system, transportation signage in the 1960s, Unimark International and, of course, Helvetica. These four strands are woven together, over nine pages, to tell a story that ultimately transcends the simple issue of Helvetica and the subway. The Labyrinth As any New Yorker—or visitor to the city—knows, the subway system is a labyrinth. This is because it is an amalgamation of three separate systems, two of which incorporated earlier urban railway lines. The current New York subway system was formed in 1940 when the IRT (Interborough Rapid Transit), the BMT (Brooklyn-Manhattan Transit) and the IND (Independent) lines were merged. The IRT lines date to 1904; the BMT lines to 1908 (when it was the BRT, or Brooklyn Rapid Transit); and the IND to 1932. -

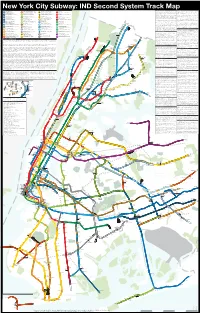

Page 1 Scale of Miles E 177Th St E 163Rd St 3Rd Ave 3Rd Ave 3Rd a Ve

New York City Subway: IND Second System Track Map Service Guide 1: 2nd Avenue Subway (1929-Present) 10: IND Fulton St Line Extensions (1920s-1960s) 8th Av, Fulton St Exp. 6th Av Local, Rockaway, Staten Island Lcl. 2 Av Lcl, Broadway Exp, Brighton Beach Locl. 7th Av Local. The 2nd Ave Subway has been at the heart of every expansion proposal since the IND Second The IND Fulton St Subway was a major trunk line built to replace the elevated BMT Fulton St-Liberty Ave 207 St to Jamaica-168 St, Bay Ridge-86 St to Jacob Riis-Beach 149 St. 2 Av-96 St to Stillwell Av-Coney Island. Van Cortlandt Park-242 St to South Ferry. System was first announced. The line has been redesigned countless times, from a 6-track trunk line. The subway was largely built directly below the elevated structure it replaced. It was initially A Queens Village-Sprigfield Blvd. H Q 1 line to the simple 2-track branch we have today. The map depicts the line as proposed in 1931 designed as a major through route to southern Queens. Famously, the Nostrand Ave station was with 6 tracks from 125th St to 23rd St, a 2-track branch through Alphabet City into Williamsburg, 4 originally designed to only be local to speed up travel for riders coming from Queens; it was converted to 8th Av, Fulton St Exp. Brooklyn-Queens Crosstown Local. 2 Av Lcl, Broadway Exp, Brighton Beach Locl. 7th Av Exp. tracks from 23rd St to Canal St, a 2-track branch to South Williamsburg, and 2 tracks through the an express station when ambitions cooled. -

"Its Cargo Is People": Repositioning Commuter Rail As Public Transit to Save the New York–New Haven Line, 1960–1990 Seamus C

Yale University EliScholar – A Digital Platform for Scholarly Publishing at Yale Harvey M. Applebaum ’59 Award Library Prizes July 2019 "Its Cargo Is People": Repositioning Commuter Rail as Public Transit to Save the New York–New Haven Line, 1960–1990 Seamus C. Joyce-Johnson Yale University Follow this and additional works at: https://elischolar.library.yale.edu/applebaum_award Part of the Social History Commons, United States History Commons, and the Urban, Community and Regional Planning Commons Recommended Citation Joyce-Johnson, Seamus C., ""Its Cargo Is People": Repositioning Commuter Rail as Public Transit to Save the New York–New Haven Line, 1960–1990" (2019). Harvey M. Applebaum ’59 Award. 18. https://elischolar.library.yale.edu/applebaum_award/18 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Library Prizes at EliScholar – A Digital Platform for Scholarly Publishing at Yale. It has been accepted for inclusion in Harvey M. Applebaum ’59 Award by an authorized administrator of EliScholar – A Digital Platform for Scholarly Publishing at Yale. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “Its Cargo Is People”: Repositioning Commuter Rail as Public Transit to Save the New York–New Haven Line, 1960–1990 Senior Essay Department of History Silliman College Yale University by Seamus Joyce-Johnson Faculty Advisor: Paul Sabin April 1, 2019 Abstract This essay explores the creation of the Metro-North Railroad in 1983 as a public agency to provide commuter train services on the New York–New Haven Line. The essay begins by bringing out the central role commuter rail services played in the negotiations over the New Haven Railroad’s bankruptcy in the 1960s.