ARTH3525 Topics in Renaissance Art History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Master of the Unruly Children and His Artistic and Creative Identities

The Master of the Unruly Children and his Artistic and Creative Identities Hannah R. Higham A Thesis Submitted to The University of Birmingham For The Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of Art History, Film and Visual Studies School of Languages, Art History and Music College of Arts and Law The University of Birmingham May 2015 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT This thesis examines a group of terracotta sculptures attributed to an artist known as the Master of the Unruly Children. The name of this artist was coined by Wilhelm von Bode, on the occasion of his first grouping seven works featuring animated infants in Berlin and London in 1890. Due to the distinctive characteristics of his work, this personality has become a mainstay of scholarship in Renaissance sculpture which has focused on identifying the anonymous artist, despite the physical evidence which suggests the involvement of several hands. Chapter One will examine the historiography in connoisseurship from the late nineteenth century to the present and will explore the idea of the scholarly “construction” of artistic identity and issues of value and innovation that are bound up with the attribution of these works. -

Madonna and Child with Donor

National Gallery of Art NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART ONLINE EDITIONS Italian Paintings of the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries Lippo Memmi Sienese, active 1317/1347 Madonna and Child with Donor 1325/1330 tempera on panel painted surface: 50.8 × 23.5 cm (20 × 9 1/4 in.) overall: 51.5 × 24.2 × 0.5 cm (20 1/4 × 9 1/2 × 3/16 in.) framed: 70 x 36.2 x 5.1 cm (27 9/16 x 14 1/4 x 2 in.) Andrew W. Mellon Collection 1937.1.11 ENTRY The painting’s iconography is based on the type of the Hodegetria Virgin. [1] It presents, however, a modernized version of this formula, in keeping with the “humanized” faith and sensibility of the time; instead of presenting her son to the observer as in the Byzantine model, Mary’s right hand touches his breast, thus indicating him as the predestined sacrificial lamb. As if to confirm this destiny, the child draws his mother’s hand towards him with his left hand. The gesture of his other hand, outstretched and grasping the Madonna’s veil, can be interpreted as a further reference to his Passion and death. [2] The painting probably was originally the left wing of a diptych. The half-length Madonna and Child frequently was combined with a representation of the Crucifixion, with or without the kneeling donor. In our panel, the donor, an unidentified prelate, is seen kneeling to the left of the Madonna; his position on the far left of the composition itself suggests that the panel was intended as a pendant to a matching panel to the right. -

The Collaboration of Niccolò Tegliacci and Luca Di Tommè

The Collaboration of Niccolô Tegliacci and Lúea di Tomme This page intentionally left blank J. PAUL GETTY MUSEUM Publication No. 5 THE COLLABORATION OF NICCOLÔ TEGLIACCI AND LUCA DI TOMMÈ BY SHERWOOD A. FEHM, JR. !973 Printed by Anderson, Ritchie & Simon Los Angeles, California THE COLLABORATION OF NICCOLO TEGLIACCI AND LUCA DI TOMMÈ The economic and religious revivals which occurred in various parts of Italy during the late Middle Ages brought with them a surge of .church building and decoration. Unlike the typically collective and frequently anonymous productions of the chan- tiers and ateliers north of the Alps which were often passed over by contemporary chroniclers of the period, artistic creativity in Italy during the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries documents the emergence of distinct "schools" and personalities. Nowhere is this phenomenon more apparent than in Tuscany where indi- vidual artists achieved sufficient notoriety to appear in the writ- ings of their contemporaries. For example, Dante refers to the fame of the Florentine artist Giotto, and Petrarch speaks warmly of his Sienese painter friend Simone Martini. Information regarding specific artists is, however, often l^ck- ing or fragmentary. Our principal source for this period, The Lives of the Painters, Sculptors and Architects by Giorgio Vasari, was written more than two hundred years after Giotto's death. It provides something of what is now regarded as established fact often interspersed with folk tales and rumor. In spite of the enormous losses over the centuries, a large num- ber of paintings survived from the Dugento and Trecento. Many of these are from Central Italy, and a relatively small number ac- tually bear the signature of the artist who painted them. -

Painting in Renaissance Siena

Figure r6 . Vecchietta. The Resurrection. Figure I7. Donatello. The Blood of the Redeemer. Spedale Maestri, Torrita The Frick Collection, New York the Redeemer (fig. I?), in the Spedale Maestri in Torrita, southeast of Siena, was, in fact, the common source for Vecchietta and Francesco di Giorgio. The work is generally dated to the 1430s and has been associated, conjecturally, with Donatello's tabernacle for Saint Peter's in Rome. 16 However, it was first mentioned in the nirieteenth century, when it adorned the fa<;ade of the church of the Madonna della Neve in Torrita, and it is difficult not to believe that the relief was deposited in that provincial outpost of Sienese territory following modifications in the cathedral of Siena in the seventeenth or eighteenth century. A date for the relief in the late I4 5os is not impossible. There is, in any event, a curious similarity between Donatello's inclusion of two youthful angels standing on the edge of the lunette to frame the composition and Vecchietta's introduction of two adoring angels on rocky mounds in his Resurrection. It may be said with little exaggeration that in Siena Donatello provided the seeds and Pius II the eli mate for the dominating style in the last four decades of the century. The altarpieces commissioned for Pienza Cathedral(see fig. IS, I8) are the first to utilize standard, Renaissance frames-obviously in con formity with the wishes of Pius and his Florentine architect-although only two of the "illustrious Si enese artists," 17 Vecchietta and Matteo di Giovanni, succeeded in rising to the occasion, while Sano di Pietro and Giovanni di Paolo attempted, unsuccessfully, to adapt their flat, Gothic figures to an uncon genial format. -

The Presentation of the Virgin in the Temple

National Gallery of Art NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART ONLINE EDITIONS Italian Paintings of the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries Paolo di Giovanni Fei Sienese, c. 1335/1345 - 1411 The Presentation of the Virgin in the Temple 1398-1399 tempera on wood transferred to hardboard painted surface: 146.1 × 140.3 cm (57 1/2 × 55 1/4 in.) overall: 147.2 × 140.3 cm (57 15/16 × 55 1/4 in.) Samuel H. Kress Collection 1961.9.4 ENTRY The legend of the childhood of Mary, mother of Jesus, had been formed at a very early date, as shown by the apocryphal Gospel of James, or Protoevangelium of James (second–third century), which for the first time recounted events in the life of Mary before the Annunciation. The iconography of the presentation of the Virgin that spread in Byzantine art was based on this source. In the West, the episodes of the birth and childhood of the Virgin were known instead through another, later apocryphal source of the eighth–ninth century, attributed to the Evangelist Matthew. [1] According to this account of her childhood, Mary, on reaching the age of three, was taken by her parents, together with offerings, to the Temple of Jerusalem, so that she could be educated there. The child ascended the flight of fifteen steps of the temple to enter the sacred building, where she would continue to live, fed by an angel, until she reached the age of fourteen. [2] The legend linked the child’s ascent to the temple and the flight of fifteen steps in front of it with the number of Gradual Psalms. -

Review of Anita Fiderer Moskowitz, Nicola & Giovanni Pisano

Peregrinations: Journal of Medieval Art and Architecture Volume 2 Issue 3 1-3 2009 Review of Anita Fiderer Moskowitz, Nicola & Giovanni Pisano: The Pulpits: Pious Devotion/Pious Diversion Peter Dent Courtauld Institute Follow this and additional works at: https://digital.kenyon.edu/perejournal Part of the Ancient, Medieval, Renaissance and Baroque Art and Architecture Commons Recommended Citation Dent, Peter. "Review of Anita Fiderer Moskowitz, Nicola & Giovanni Pisano: The Pulpits: Pious Devotion/ Pious Diversion." Peregrinations: Journal of Medieval Art and Architecture 2, 3 (2009): 1-3. https://digital.kenyon.edu/perejournal/vol2/iss3/16 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Kenyon: Research, Scholarship, and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Peregrinations: Journal of Medieval Art and Architecture by an authorized editor of Digital Kenyon: Research, Scholarship, and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Dent BOOK REVIEWS Review of Anita Fiderer Moskowitz, with photographs by David Finn, Nicola & Giovanni Pisano: The Pulpits: Pious Devotion – Pious Diversion, (London, Harvey Miller, 2005), 362pp., ills. 329 b/w, 8 colour, €125 ($156), ISBN 1-872501-49 By Peter Dent (Courtauld Institute, London) Nicola & Giovanni Pisano: The Pulpits: Pious Devotion – Pious Diversion by Anita Fiderer Moskowitz is the first monograph devoted entirely to these fundamental works of late medieval Italian sculpture. It is an attractive volume, largely down to the extensive set of new photographs commissioned from David Finn, an initiative that should be applauded. Although the decision (defended and discussed in the Preface) to present a “sculptor‟s” rather than a beholder‟s eye view raises methodological issues, there are some magnificent images here. -

Sources of Donatello's Pulpits in San Lorenzo Revival and Freedom of Choice in the Early Renaissance*

! " #$ % ! &'()*+',)+"- )'+./.#')+.012 3 3 %! ! 34http://www.jstor.org/stable/3047811 ! +565.67552+*+5 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=caa. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit organization founded in 1995 to build trusted digital archives for scholarship. We work with the scholarly community to preserve their work and the materials they rely upon, and to build a common research platform that promotes the discovery and use of these resources. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. http://www.jstor.org THE SOURCES OF DONATELLO'S PULPITS IN SAN LORENZO REVIVAL AND FREEDOM OF CHOICE IN THE EARLY RENAISSANCE* IRVING LAVIN HE bronze pulpits executed by Donatello for the church of San Lorenzo in Florence T confront the investigator with something of a paradox.1 They stand today on either side of Brunelleschi's nave in the last bay toward the crossing.• The one on the left side (facing the altar, see text fig.) contains six scenes of Christ's earthly Passion, from the Agony in the Garden through the Entombment (Fig. -

Alberto Aringhieri and the Chapel of Saint John the Baptist: Patronage, Politics, and the Cult of Relics in Renaissance Siena Timothy B

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2002 Alberto Aringhieri and the Chapel of Saint John the Baptist: Patronage, Politics, and the Cult of Relics in Renaissance Siena Timothy B. Smith Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF VISUAL ARTS AND DANCE ALBERTO ARINGHIERI AND THE CHAPEL OF SAINT JOHN THE BAPTIST: PATRONAGE, POLITICS, AND THE CULT OF RELICS IN RENAISSANCE SIENA By TIMOTHY BRYAN SMITH A Dissertation submitted to the Department of Art History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Fall Semester, 2002 Copyright © 2002 Timothy Bryan Smith All Rights Reserved The members of the Committee approve the dissertation of Timothy Bryan Smith defended on November 1 2002. Jack Freiberg Professor Directing Dissertation Mark Pietralunga Outside Committee Member Nancy de Grummond Committee Member Robert Neuman Committee Member Approved: Paula Gerson, Chair, Department of Art History Sally McRorie, Dean, School of Visual Arts and Dance The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the abovenamed committee members. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First I must thank the faculty and staff of the Department of Art History, Florida State University, for unfailing support from my first day in the doctoral program. In particular, two departmental chairs, Patricia Rose and Paula Gerson, always came to my aid when needed and helped facilitate the completion of the degree. I am especially indebted to those who have served on the dissertation committee: Nancy de Grummond, Robert Neuman, and Mark Pietralunga. -

Madonna and Child with the Blessing Christ, and Saints Mary Magdalene

National Gallery of Art NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART ONLINE EDITIONS Italian Paintings of the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries Pietro Lorenzetti Sienese, active 1306 - 1345 Madonna and Child with the Blessing Christ, and Saints Mary Magdalene and Catherine of Alexandria with Angels [entire triptych] probably 1340 tempera on panel transferred to canvas Inscription: middle panel, across the bottom edge, on a fragment of the old frame set into the present one: [PETRUS] L[A]URENTII DE SENIS [ME] PI[N]XIT [ANNO] D[OMI]NI MCCCX...I [1] Gift of Frieda Schiff Warburg in memory of her husband, Felix M. Warburg 1941.5.1.a-c ENTRY The central Madonna and Child of this triptych, which also includes Saint Catherine of Alexandria, with an Angel [right panel] and Saint Mary Magdalene, with an Angel [left panel], proposes a peculiar variant of the so-called Hodegetria type. The Christ child is supported on his mother’s left arm and looks out of the painting directly at the observer, whereas Mary does not point to her son with her right hand, as is usual in similar images, but instead offers him cherries. The child helps himself to the proffered fruit with his left hand, and with his other is about to pop one of them into his mouth. [1] Another unusual feature of the painting is the smock worn by the infant Jesus: it is embellished with a decorative band around the chest; a long, fluttering, pennant-like sleeve (so-called manicottolo); [2] and metal studs around his shoulders. The group of the Madonna and Child is flanked by two female saints. -

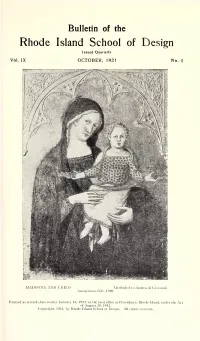

Bulletin of Rhode Island School of Design

Bulletin of the Rhode Island School of Design Issued Quarterly Vol. IX OCTOBER, 1921 No. 4 MADONNA AND CHILD Attributed to Andrea di Giovanni Anonymous Gift, 1920 Entered as second-class matter January 16, 1913, at the post office at Providence, Rhode Island, under the Act of August 24, 1912. Copyright, 1921, by Rhode Island School of Design. All rights reserved. IX, 34 Bulletin of the Rhode Island School of Design MADONNA AND CHILD, he painted in collaboration in 1372, and ATTRIBUTED TO he not infrequently repeated that master’s ANDREA DI GIOVANNI forms, though in a somewhat coarse manner. Pietro da Puccio executed in HE Rhode Island School of Design 1390 the mediocre frescoes of scenes from at Providence has acquired an ex- Genesis on the north wall of the Campo- T santo of ceptionally attractive panel picture Pisa. Of Cola da Petruccioli, of the Madonna and Child, which ap- Mr. Berenson has recently written, iden- pears at first sight to be a product of tifying this modest and not always attrac- 1 the Sienese school of the latter part of tive artist as a follower of Fei. the 14th century. No one will deny the A number of documents exist which en- Sienese character of the picture, although able us to follow the career of Andrea di closer study may suggest its attribution to Giovanni from 1370 to 1417. At the for- Andrea di Giovanni, a painter of Orvieto. mer date he was working with Cola da I recently had occasion to call attention Petruccioli and other painters, under the to the fact that even as late as the begin- direction of Ugolino da Prete Ilario, on the ing of the 15th century painting at Orvieto tribune of the Cathedral of Orvieto; but was dominated by the artistic tradition it is impossible to distinguish in these 1 of Simone Martini. -

Catalogue Entry

CALLISTO FINE ARTS 17 Georgian House 10 Bury Street London SW1Y 6AA +44 (0)207 8397037 [email protected] www.callistoart.com Jacopo della Quercia (Quercegrossa, c.1372 – Siena, 1438) Warrior Saint c.1426-1430 Marble 53x23x14 cm Bibliography: Casciaro, Raffaele, “Celsis Florentia nota tropheis”, in Raffaele Casciaro e Paola Di Girolami, a cura di, Jacopo della Quercia ospite a Ripatransone, Tracce di scultura toscana tra Emilia e Marche. Ripatransone, Firenze, 2008, pp. 21-39 Custoza, Gian Camillo, con prefazione di Giancarlo Gentilini, “Jacopo della Quercia. San Paolo”, Venezia, 2011 Gentilini, Giancarlo, introduzione di, David Lucidi, con la collaborazione di, “Scultura italiana del Rinascimento”, Firenze, 2013, pp. 13-15 CALLISTO FINE ARTS 17 Georgian House 10 Bury Street London SW1Y 6AA +44 (0)207 8397037 [email protected] www.callistoart.com Gentilini, Giancarlo, scheda, in Massimo Pulini, a cura di, “Lo Studiolo di Baratti”, Cesena, 2010, cat. 1, pp. 30-33 Ortenzi, Francesco, in “Lo Studiolo di Baratti”, catalogo della mostra (Cesena 2010), a cura di M. Pulini, Cesena 2010, pp. 30-33 n. 1; Ortenzi, Francesco, scheda, in Raffaele Casciaro e Paola Di Girolami, a cura di, “Jacopo Della Quercia ospite a Ripatransone. Tracce di scultura toscana tra Emilia e Marche”. Ripatransone, Firenze, 2008, cat. 5, pp. 64-68 Exhibitions: “Scultura italiana del Rinascimento”, a cura di Giancarlo Gentilini e David Lucidi, Firenze, The Westin Excelsior, 5-9 ottobre 2013 “Lo Studiolo di Baratti”, a cura di Massimo Pulini, Cesena, Galleria Comunale d’Arte, 6 febbraio – 11 aprile 2010 “Jacopo della Quercia ospite a Ripatransone. Tracce di scultura toscana tra Emilia e Marche”, a cura di Raffaele Casciaro e Paola Di Girolami, Ripatransone, Chiesa di Sant’Agostino, 28 giugno – 14 settembre 2008 This marvellous work has been attributed to Jacopo della Quercia by Francesco Ortenzi in 2008 and by Giancarlo Gentilini in 2011. -

The Mariology of St. Bonaventure As a Source of Inspiration in Italian Late Medieval Iconography

José María SALVADOR GONZÁLEZ, La mariología de San Buenaventura como fuente de inspiración en la iconografía bajomedieval italiana The mariology of St. Bonaventure as a source of inspiration in Italian late medieval iconography La mariología de San Buenaventura como fuente de inspiración en la iconografía bajomedieval italiana1 José María SALVADOR-GONZÁLEZ Universidad Complutense de Madrid [email protected] Recibido: 05/09/2014 Aceptado: 05/10/2014 Abstract: The central hypothesis of this paper raises the possibility that the mariology of St. Bonaventure maybe could have exercised substantial, direct influence on several of the most significant Marian iconographic themes in Italian art of the Late Middle Ages. After a brief biographical sketch to highlight the prominent position of this saint as a master of Scholasticism, as a prestigious writer, the highest authority of the Franciscan Order and accredited Doctor of the Church, the author of this paper presents the thesis developed by St. Bonaventure in each one of his many “Mariological Discourses” before analyzing a set of pictorial images representing various Marian iconographic themes in which we could detect the probable influence of bonaventurian mariology. Key words: Marian iconography; medieval art; mariology; Italian Trecento painting; St. Bonaventure; theology. Resumen: La hipótesis de trabajo del presente artículo plantea la posibilidad de que la doctrina mariológica de San Buenaventura haya ejercido notable influencia directa en varios de los más significativos temas iconográficos