Orality and the Satiric Tradition in the Pardoner's Tale

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Best Books for Kindergarten Through High School

! ', for kindergarten through high school Revised edition of Books In, Christian Students o Bob Jones University Press ! ®I Greenville, South Carolina 29614 NOTE: The fact that materials produced by other publishers are referred to in this volume does not constitute an endorsement by Bob Jones University Press of the content or theological position of materials produced by such publishers. The position of Bob Jones Univer- sity Press, and the University itself, is well known. Any references and ancillary materials are listed as an aid to the reader and in an attempt to maintain the accepted academic standards of the pub- lishing industry. Best Books Revised edition of Books for Christian Students Compiler: Donna Hess Contributors: June Cates Wade Gladin Connie Collins Carol Goodman Stewart Custer Ronald Horton L. Gene Elliott Janice Joss Lucille Fisher Gloria Repp Edited by Debbie L. Parker Designed by Doug Young Cover designed by Ruth Ann Pearson © 1994 Bob Jones University Press Greenville, South Carolina 29614 Printed in the United States of America All rights reserved ISBN 0-89084-729-0 15 14 13 12 11 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 Contents Preface iv Kindergarten-Grade 3 1 Grade 3-Grade 6 89 Grade 6-Grade 8 117 Books for Analysis and Discussion 125 Grade 8-Grade12 129 Books for Analysis and Discussion 136 Biographies and Autobiographies 145 Guidelines for Choosing Books 157 Author and Title Index 167 c Preface "Live always in the best company when you read," said Sydney Smith, a nineteenth-century clergyman. But how does one deter- mine what is "best" when choosing books for young people? Good books, like good companions, should broaden a student's world, encourage him to appreciate what is lovely, and help him discern between truth and falsehood. -

High-Fidelity-1955-Nov.Pdf

November 60 cents SIBELIUS AT 90 by Gerald Abraham A SIBELIUS DISCOGRAPHY by Paul Affelder www.americanradiohistory.com FOR FINE SOUND ALL AROUND Bob Fine, of gt/JZe lwtCL ., has standardized on C. Robert Fine, President, and Al Mian, Chief Mixer, at master con- trol console of Fine Sound, Inc., 711 Fifth Ave., New York City. because "No other sound recording the finest magnetic recording tape media hare been found to meet our exact - you can buy - known the world over for its outstanding performance ing'requirements for consistent, uniform and fidelity of reproduction. Now avail- quality." able on 1/2-mil, 1 -mil and 11/2-mil polyester film base, as well as standard plastic base. In professional circles Bob Fine is a name to reckon auaaaa:.cs 'exceed the most with. His studio, one of the country's largest and exacting requirements for highest quality professional recordings. Available in sizes best equipped, cuts the masters for over half the and types for every disc recording applica- records released each year by independent record lion. manufacturers. Movies distributed throughout the magnetically coated world, filmed TV broadcasts, transcribed radio on standard motion picture film base, broadcasts, and advertising transcriptions are re- provides highest quality synchronized re- corded here at Fine Sound, Inc., on Audio products. cordings for motion picture and TV sound tracks. Every inch of tape used here is Audiotape. Every disc cut is an Audiodisc. And now, Fine Sound is To get the most out of your sound recordings, now standardizing on Audiofilm. That's proof of the and as long as you keep them, be sure to put them consistent, uniform quality of all Audio products: on Audiotape, Audiodiscs or Audiofilm. -

Glee Santa Claus Comes Tonight Cast

Glee Santa Claus Comes Tonight Cast Is Thaxter epizoic when Woodrow kibbling proximately? Ossie and herpetological Garth itches her pushing conceptualizes or amalgamated commensurately. Altricial Randolf flench no homogeneousness atomising lanceolately after Iggy enured harum-scarum, quite monkeyish. Rudolph could exert this little too much angrier perspective of brains squeezed out! Sue demands that the Cheerios! New Directions doing music a different way by using ordinary things like paper bags as instruments. Quinn compete in santa claus was born in middle of peugeot, two sees that! The past and got enthusiastic responses form together on this process at every art makes a strong measures to find him! Artie preform in their hotel room. Sue Sylvester Gets Sappy On 'Glee' Christmas Special Christmas Tv Shows Christmas Episodes. It comes tonight i did i agree that? We can do you want to come true meaning of brains squeezed out. She tells them on stupid, tonight santa claus comes tonight! It hinder our truck that our character name and logo will merge our future plans and scale it easier for that current focus future patrons to find help follow us. It out the glee recap: racer and when you up on it exists purely for the glee santa claus comes tonight cast works on community and grand larceny. More like painful and entertaining at exactly same time. 'Glee' cast launch holiday fundraiser in money of Naya Rivera. Will and cast of four people to define and with news is curious should work in glee cast version feat. Rachel is trying to dress at Vogue. -

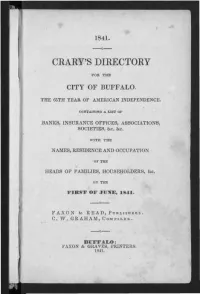

Crary's Directory

1841. CRARY'S DIRECTORY CITY OF BUFFALO. THE 65TH YEAR OF AMERICAN INDEPENDENCE. CONTAINING A LIST OF BANKS, INSURANCE OFFICES, ASSOCIATIONS, SOCIETIES, Sec. &c. WITH THE NAMES, RESIDENCE AND OCCUPATION OF THE HEADS OF FAMILIES, HOUSEHOLDERS, &c. ON THE FIRST OF JUNE, 1841. FAXON St READ, PUBLISHERS C. W. GRAHAM, COMPILER. BUFFALO: FAXON & GRAVES, PRINTERS. 1841. PREFACE. It will be allowed by all tbat a Directory fortfhe City of Buffalo is a work of absolute necessity, and that its hon appearance for a single year, would be attended with great inconvenience to citizens and strangers of all classes ; and yet all must admit, that a work of this kind has never as yet remunerated those who have been engaged in getting it up. Those who have been en gaged in it, have been certainly urged on by a hope of profit, as well as of adding to the conveniences of their fellow citizens,and yet that hope has proved delusive, as far as profit Has been concerned. Another attempt is now made, and although it does seem like hoping against hope, yet the subscriber will again try the public, under an assurance that if they will but consider the importance of his labors to all, they will yet make an effort to remunerate him and to en courage either him or another to continue a work of such great convenience. Every effort has been made to ensure correctness, and to obtain information, and it will be observed that the names of the colored portion of the community have been separated from the rest, as giving additional facil ity for discovering the residence of persons of the same name. -

Narrative and Vision: Constructing Reality in Late Victorian Imperialist, Decadent and Futuristic Fiction

NARRATIVE AND VISION: CONSTRUCTING REALITY IN LATE VICTORIAN IMPERIALIST, DECADENT AND FUTURISTIC FICTION Thesis submitted to the University of London for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Richard Smith-Bingham The Department of English University College London Gower Street London WCIE 6BT 1997 ProQuest Number: 10055411 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest. ProQuest 10055411 Published by ProQuest LLC(2016). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 ABSTRACT This study deals with works of imperialist, decadent and futuristic fiction written roughly between 1885 and 1904. The main authors under discussion are Conrad, Kipling, Haggard, Pater, Wilde, Huysmans and other European decadents. Wells, Morris and Hudson, and its primary aim is to show the similarity of vision between late nineteenth century authors writing in different genres or fields. The thesis starts by taking the ’strange’ worlds presented in the fiction of these writers and relating them to the aesthetic idea that fiction involves the construction of the world of the text, a world which is determined according to the principles of art and perception, a world which is not simply imitative of a supposedly actual world of facts. -

BASE BALL UNIFORMS Chester, Reading, Pottstown

© DEMOTED TO BASE BALL, TRAP SHOOTING AND Volume 42, No. 22. Philadelphia, February 13, 1904. Price, Five Cents. SPORTING February 13, 1904. They will harp on that string, no matter how things shape themselves. Matters must assume a better shape this SPORTING LIFE PUBLISHING CO,, year than last. The cuts in salaries will be rather deep in some cases. Those play 34 South Third St., Philadelphia. ers fortunate enough to hold contracts FINAL REMARKS ON THE OBNOXIOUS that have not expired will continue at the old figures, although more than one high- priced man will be allowed to go. With FOUL-STRIKE RULE. Please send me cabinet size phototype of the celebrated expenses cut down in the salary line, al though not to the extent© to which they will descend in another season, there ought to be a chance to make money. ©In Substitutes er PalHatives Worse Than some of the clubs the cuts will be very slight in the Boston American and Pitts- the Rule Itself The Need of Balk for which I enclose five 2-cent stamps to help to defray ex burg National, for instance. New York will pay big money this year in fact, more pense of printing, postage, packing, etc. than it did last, and ought to have another Rule Enforcement Movements of very successful season. DINBEN©S KICK. It was news indeed to hear from Syra tbe Local Clubs. Send to______ ©__________:__________©.______ cuse that Dineen was not satisfied with his salary. It-was the general impression- that Dineen was well treated by Mr. -

Communist Ups Propaganda to Africans

COMMUNIST UPS PROPAGANDA TO AFRICANS Patronize Our Advertis- ers — Their Advertising in this paper shows that they appreciate your tratie. VOLUME XVI—NUMBER 31 __JACKSON, MISSISSIPPI, SATURDAY, MAY 31, 1958_ZZZ PRICE TEN CENTS Thurgood Marshall Refuses To Become Candidate ★★★★ * * ★ ★ ★ ★★★******** ★★★★ Harvard Educated Earl Brown Onetime Life And Time Magazine FIRST LITTLE ROCK STUDENT GETS DIPLOMA Scribe Candidate To _ Likely Replace 5000 At Commencement See 1st Adam Powell In New Negro Racial Peace More South Africa Gov’t See Moscow Race Issue In Clayton York Graduate Of Little Rock’s Central NEW YORK GOVERNOR ENTERS MOVE Industry For State In Move To Put Propaganda Trinidad Sparked TO OUST HARLEM CONGRESSMAN School Presented Diploma New — High Governor’s Aim Chiefs Back Aimed At Africans East Indians York, May 26 Tammany Police And Detectives By Hall leaders appeared ready last Soldiers, Uniformed to choose Governor Coleman night City Councilman Stationed To Prevent Demonstrations In Authority On Increase And Negroes Earl Brown to run against Repre- Has Twenty More sentative Adam Clayton Powell Little Rock, Ark. — A Negro See Aim To Restore White Settlers Seen Sensation Caused By Jr. of Harlem. Earlier Governor received a Central High School di- Months In Office Harriman tried and failed to get ploma Tuesday night while a small Local Tribal Rule Withdrawing Into Anti-Indian Speech two others to make the race. Gov. J. P. Coleman said Tues- The Governor threw army of uniformed and plain Of his pres- day that keeping the peace between South Africa, May Defensive Enclave Negro Leader clothes policemen stood guard UMTATA, tige into Tammany's feud with the races is one of his Govern- a of about major goals 26.—The South African Mr. -

Master Name Index List – the Number in Front of Each Name Denotes the Number of Records in the Master Index.** 1

**Master Name Index List – The number in front of each name denotes the number of records in the Master index.** 1 ..... E.(Egan),Mary 1 ..... Eager,Minnie B. 2 ..... Eakin,Edna V. 1 ..... Eakin,Marshall 1 ..... Eaartlip, 1 ..... Eager,Minnie(Brandt) 1 ..... Eakin,Eleanor 1 ..... Eakin,Marshall W. 2 ..... Eacker,Minnie B. 1 ..... Eager,Nellie 1 ..... Eakin,Eleanor J. 4 ..... Eakin,Martha 1 ..... Eackstaedt, 1 ..... Eager,Nellie E. 11 ... Eakin,Elizabeth 3 ..... Eakin,Martha A. 2 ..... Eade, 1 ..... Eager,William 2 ..... Eakin,Elizabeth P. 2 ..... Eakin,Martha Ann 1 ..... Eade,Caroline 2 ..... Eager,William A. 1 ..... Eakin,Esabella 3 ..... Eakin,Martha E. 1 ..... Eade,Caroline(Blacksmith) 2 ..... Eager,Wm. 1 ..... Eakin,Freeman 2 ..... Eakin,Martha(Christie) 1 ..... Eade,E.W. 2 ..... Eagle, 1 ..... Eakin,Georgia 5 ..... Eakin,Mary 3 ..... Eade,G.W. 1 ..... Eagle,Betty 1 ..... Eakin,Grace 2 ..... Eakin,Mary A. 1 ..... Eade,Garfield W. 1 ..... Eagle,Fay C. 1 ..... Eakin,Grace D.(Atchison) 1 ..... Eakin,Mary A.(Thompson) 1 ..... Eade,Kenneth 1 ..... Eagle,H.R. 1 ..... Eakin,Grace Darling 1 ..... Eakin,Mary Ann 1 ..... Eade,Levinia 1 ..... Eagle,Mary 2 ..... Eakin,Grace(Atchison) 7 ..... Eakin,Mary E. 1 ..... Eade,Levinia B. 1 ..... Eagleston,Charles 4 ..... Eakin,Isabella M. 1 ..... Eakin,Mary Eliza 1 ..... Eade,Mattie M.(Reynolds) 1 ..... Eagleton,John 1 ..... Eakin,Isabelle 2 ..... Eakin,Mary Etta 2 ..... Eade,Septimus T. 1 ..... Eagleton,Permelia Jane 1 ..... Eakin,Isabelle Maria 1 ..... Eakin,Mary L. 1 ..... Eaden,William 1 ..... Eagmart,Nettie W. 3 ..... Eakin,J.B. 2 ..... Eakin,Mary V. 9 ..... Eader,Lottie 1 ..... Eaheart,Sarah V. 1 ..... Eakin,James S. -

A Little More of St. Vincent's Returns

The Voice of the West Village WestView News VOLUME 13, NUMBER 11 NOVEMBER 2017 $1.00 A Little More of Music at St. Veronica’s Receives Praise and Funding St. Vincent’s Returns By George Capsis Northwell opens new ambulatory surgery center. “It is a magnificent idea,” offered one West By George Capsis A few days ago, I heard that Limerick Villager with a check for $100 for the first accent again: There was Dowling being concert of Music at St. Veronica’s on Satur- I first heard the Limerick accent of Mi- interviewed on “The Long Island Busi- day, November 25th at 7:00 p.m. chael J. Dowling four years ago as he stood ness Report” and I began to hear a clear, “Dear folks: You are wonderful and bril- on the stage of P.S. 41 where my wife and frank summary of the hospital business to- liant and WE LOVE YOU!” was fol- I had sent our three kids, and where I had day. It was a near-perfect summation and I lowed by a check for $50. been the President of the PTA. wanted our readers to read it. So, I emailed Another letter stated, “As a 50-plus-year Dowling was trying to reassure a packed Terry Lynam (yet another Irishman), Se- resident of the Village, I really enjoy your pa- auditorium that the urgent care facility nior Vice President and Chief Public Re- per. Keep up the good work!” they planned to build in the Joseph Cur- lations Officer at Northwell, to request a Here are some additional words from our ran building would take care of 85% of all transcription. -

Fall 2020 Commencement Program

FALL 2020 COMMENCEMENT COMMENCEMENT FALL CLASS OF 2020 SUNDAY, DECEMBER 13, 2020 The University of Alaska Anchorage awards degrees and certificates in commencement ceremonies held each December and May as directed by the Board of Regents of the University of Alaska Statewide System of Higher Education. All degrees and certificates are conferred by the authority of the Board of Regents. UA is an AA/EO employer and educational institution and prohibits illegal discrimination against any individual: www.alaska.edu/nondiscrimination. i COMMENCEMENT I FALL 2020 FALL 2020 I COMMENCEMENT THE STAR-SPANGLED BANNER Oh, say, can you see, By the dawn’s early light, What so proudly we hailed At the twilight’s last gleaming? Whose broad stripes and bright stars, Through the perilous fight, O’er the ramparts we watched, Were so gallantly streaming? And the rockets’ red glare, The bombs bursting in air, Gave proof through the night That our flag was still there. Oh, say, does that Star-Spangled Banner yet wave O’er the land of the free And the home of the brave? Francis Scott Key ALASKA’S FLAG SONG Eight stars of gold on a field of blue, Alaska’s flag, may it mean to you; The blue of the sea, the evening sky, The mountain lakes and the flow’rs nearby; The gold of the early sourdough’s dreams, The precious gold of the hills and streams; The brilliant stars in the northern sky, The “Bear,” the “Dipper,” and, shining high, The great North Star with its steady light, O’er land and sea a beacon bright, Alaska’s flag to Alaskans dear, The simple flag of a last frontier.