ED124945.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

B. Dilihat Dari Sejarah Kampung Beting Ini Yang Dibangun Dari

BAB IV TINJAUAN KARAKTERISTIK PERKAMPUNGAN ATAS AIR STUDI KASUS PADA PERKAMPUNGAN BETING DI KOTAMADYA PONTIANAK 4.1. Latar belakang Terpilihnya Perkampungan Beting sebagai bahan studi kasus perkampungan atas air adalah karena beberapa pertimbangan sebagai berikut: a Lotaknya yang berada di Kotamadya Pontianak, sehingga: - memudahkan melakukan survey / pengamalan - diketahui merupakan salah satu ciri perkampungan atas air yang ada di Kota Pontianak - sesuai dengan lokasi Pusat Rekreasi Marina ini yang direncanakan berada di KotaPontianak b. Dilihat dari sejarah Kampung Beting ini yang dibangun dari fiolosofi Kota Air hingga saat ini masih eksis keberadaannya c Kampung Beting dinilai cukup mewakili dari beberapa perkampungan atas airyang adadi KotaPontianak d. Pernah ada yang mencoba menggali potensi pariwisata di desa ini yaitu konsultan perencanaan PT. Makara Adiyasa, dalam Proyek Peremajaan Kampung Beting Kotamadya Pontianak, sehingga hasil-hasil laporannya dapat digunakan sebagai bahan referensi. Pusat Rekreasi Marina IV-1 4.2. Pengertian Suatu perkampungan atas air dapat diartikan sebagai suatu perkampungan pendudukyang membangun ramah-rumah tinggalnyadi atas air, dimana air di sini sifatnya bergerak secara alami. Dilihat berdasarkan lokasinya, maka perkampungan atas air ini dapat dibedakan menjadi : 1) perkampungan atas air di tepian sungai 2) perkampungan air di tepian laut (pantai) 3) perkampungan atas air di tepian waduk/danau. Kemudian jika dilihat berdasarkan bentuk rumahnya, dapat dibedakan menjadi : a bentukramah panggung b. -

Isymbols of Water and Woman on Selected Examples of Modern Bengali Literature in the Context of Mythological Tradition.*

© Wagadu Volume 3: Spring 2006 Symbols of Water and Woman iSymbols of Water and Woman on Selected Examples of Modern Bengali Literature in the Context of Mythological Tradition.* Blanka Knotková-Čapková As in many archaic mythological concepts, the four basic elements are represented in the Indian mythology as either male or female: air (wind) and fire are male principles, later personified as male deities – Agni and Vāyu; earth and water (river) are female. The metaphorization of woman as Water and Earthii has a strong essentialist aspect; it points to the symbol of the womb, the mysterious feminine source of life, the “cradle and grave”iii or “womb and tomb”, “the Great Mother symbolizing circularity of life and death” (cf. Kalnická, in Wilkoszewska 2001, 107), who also disposes with the ultimate power over life and death. As such, she personifies the female creative and dynamic cosmic energy, śakti. Together with her male counterpart (personified as male God Śiva), she represents the dual image of cosmical unity and harmony. In heterodox śaktism, she is worshipped as the ultimate spiritual principle, not dependent on the male principle; in śivaismiv, she is described as the left part of Śiva’s body. Śaktism also worships śakti in the metonymical image of yoni, the female genitals, the location of the sensual pleasure and the beginning of life (the way to / from the womb).v Some of the mythological personifications of śakti have been partially patriarchalized and “married” to the male Gods; a possible pre-Indo-European concept of an independent motherly deity (whose image was connected with the vegetation cycle, eternal recreation and rebirth). -

The Emergence of the Mahajanapadas

The Emergence of the Mahajanapadas Sanjay Sharma Introduction In the post-Vedic period, the centre of activity shifted from the upper Ganga valley or madhyadesha to middle and lower Ganga valleys known in the contemporary Buddhist texts as majjhimadesha. Painted grey ware pottery gave way to a richer and shinier northern black polished ware which signified new trends in commercial activities and rising levels of prosperity. Imprtant features of the period between c. 600 and 321 BC include, inter-alia, rise of ‘heterodox belief systems’ resulting in an intellectual revolution, expansion of trade and commerce leading to the emergence of urban life mainly in the region of Ganga valley and evolution of vast territorial states called the mahajanapadas from the smaller ones of the later Vedic period which, as we have seen, were known as the janapadas. Increased surplus production resulted in the expansion of trading activities on one hand and an increase in the amount of taxes for the ruler on the other. The latter helped in the evolution of large territorial states and increased commercial activity facilitated the growth of cities and towns along with the evolution of money economy. The ruling and the priestly elites cornered most of the agricultural surplus produced by the vaishyas and the shudras (as labourers). The varna system became more consolidated and perpetual. It was in this background that the two great belief systems, Jainism and Buddhism, emerged. They posed serious challenge to the Brahmanical socio-religious philosophy. These belief systems had a primary aim to liberate the lower classes from the fetters of orthodox Brahmanism. -

Women in India's Freedom Struggle

WOMEN IN INDIA'S FREEDOM STRUGGLE When the history of India's figf^^M independence would be written, the sacrifices made by the women of India will occupy the foremost plofe. —^Mahatma Gandhi WOMEN IN INDIA'S FREEDOM STRUGGLE MANMOHAN KAUR IVISU LIBBARV STERLING PUBLISHERS PRIVATE LIMITED .>».A ^ STERLING PUBLISHERS PRIVATE LIMITED L-10, Green Park Extension, New Delhi-110016 Women in India's Freedom Strug^e ©1992, Manmohan Kaur First Edition: 1968 Second Edition: 1985 Third Edition: 1992 ISBN 81 207 1399 0 -4""D^/i- All rights are reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission of the publisher. PRINTED IN INDIA Published by S.K. Ghai, Managing Director, Sterling Publishers Pvt. Ltd., L-10, Green Park Extension, New Delhi-110016. Laserset at Vikas Compographics, A-1/2S6 Safdarjung Enclave, New Delhi-110029. Printed at Elegant Printers. New Delhi. PREFACE This subject was chosen with a view to recording the work done by women in various phases of the freedom struggle from 1857 to 1947. In the course of my study I found that women of India, when given an opportunity, did not lag behind in any field, whether political, administrative or educational. The book covers a period of ninety years. It begins with 1857 when the first attempt for freedom was made, and ends with 1947 when India attained independence. While selecting this topic I could not foresee the difficulties which subsequently had to be encountered in the way of collecting material. -

The Foodscape

THE FOODSCAPE Tejgaon, Dhaka By UZMA ALAM 10108012 SEMINAR II Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Architecture Department of Architecture BRAC University 2015 CONTENTS CHAPTER 01: BACKGROUND OF THE PROJECT 1.1 Project Brief 1.2 Project Introduction 1.3 Project Rationale 1.4 Aims and Objectives 1.5 Proposed Program CHAPTER 02: SITE APPRAISAL 2.1 Site Location 2.2 Site and Surroundings 2.3 Environmental Condition 2.4 SWOT Analysis CHAPTER 03: LITERATURE REVIEW 3.1 What is a Foodscape? 3.2 Branding Bangladesh through its culture 3.3 Food and Culture 3.4 Food in Bangladesh 3.5 Food and Architecture CHAPTER 04: CASE STUDY 4.1 Introduction 4.2 Spaces 4.3 International Case Study CHAPTER 05: PROGRAM AND DEVELOPMENT 5.1 Proposed Program 5.2 Developed Program 5.3 Rationale of the Program CHAPTER 06: DESIGN DEVELOPMENT 6.1 Introduction 6.2 Concept Development 6.3 Form Development and Programmatic layout 6.4 Final design drawings 6.5 FInal design model CONCLUSION REFERENCES APPENDIX Abstract The project is an attempt to allow people to discover the stunning richness of Bangladeshi culture as seen in their unique food traditions, and greatly broaden one’s own enjoyment of fine food. The aim is to make Bangladeshi food a global experience. The project should be identified by its inclusiveness, its uniqueness and its diversity. It should be a place that extends a warm welcome to everybody, capturing the spirit of Bengalis and their passion for food. Proposed as an integrated development catering to the cultural requirements of Bangladesh, the project aims to celebrate food, exploring its history, heritage, and cultural influence in Bengal. -

Mapping the Body-Politic of the Raped Woman and the Nation in Bangladesh

gendered embodiments: mapping the body-politic of the raped woman and the nation in Bangladesh Mookherjee, Nayanika . Feminist Review, suppl. War 88 (Apr 2008): 36-53. Turn on hit highlighting for speaking browsers Turn off hit highlighting Other formats: Citation/Abstract Full text - PDF (206 KB) Abstract (summary) Translate There has been much academic work outlining the complex links between women and the nation. Women provide legitimacy to the political projects of the nation in particular social and historical contexts. This article focuses on the gendered symbolization of the nation through the rhetoric of the 'motherland' and the manipulation of this rhetoric in the context of national struggle in Bangladesh. I show the ways in which the visual representation of this 'motherland' as fertile countryside, and its idealization primarily through rural landscapes has enabled a crystallization of essentialist gender roles for women. This article is particularly interested in how these images had to be reconciled with the subjectivities of women raped during the Bangladesh Liberation War (Muktijuddho) and the role of the aestheticizing sensibilities of Bangladesh's middle class in that process. [PUBLICATION ABSTRACT] Show less Full Text Translate Turn on search term navigation introduction There has been much academic work outlining the complex links between women and the nation (Yuval-Davis and Anthias, 1989; Yuval-Davis, 1997; Yuval-Davis and Werbner, 1999). Women provide legitimacy to the political projects of the nation in particular social and historical contexts (Kandiyoti, 1991; Chatterjee, 1994). This article focuses on the gendered symbolization of the nation through the rhetoric of the 'motherland' and the manipulation of this rhetoric in the context of national struggle in Bangladesh. -

5. from Janapadas to Empire

MODULE - 1 Ancient India 5 Notes FROM JANAPADAS TO EMPIRE In the last chapter we studied how later Vedic people started agriculture in the Ganga basin and settled down in permanent villages. In this chapter, we will discuss how increased agricultural activity and settled life led to the rise of sixteen Mahajanapadas (large territorial states) in north India in sixth century BC. We will also examine the factors, which enabled Magadh one of these states to defeat all others to rise to the status of an empire later under the Mauryas. The Mauryan period was one of great economic and cultural progress. However, the Mauryan Empire collapsed within fifty years of the death of Ashoka. We will analyse the factors responsible for this decline. This period (6th century BC) is also known for the rise of many new religions like Buddhism and Jainism. We will be looking at the factors responsible for the emer- gence of these religions and also inform you about their main doctrines. OBJECTIVES After studying this lesson, you will be able to explain the material and social factors (e.g. growth of agriculture and new social classes), which became the basis for the rise of Mahajanapada and the new religions in the sixth century BC; analyse the doctrine, patronage, spread and impact of Buddhism and Jainism; trace the growth of Indian polity from smaller states to empires and list the six- teen Mahajanapadas; examine the role of Ashoka in the consolidation of the empire through his policy of Dhamma; recognise the main features– administration, economy, society and art under the Mauryas and Identify the causes of the decline of the Mauryan empire. -

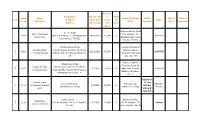

Comp. Sl. No Name S/D/W/O Designation & Office Address Date of First Application (Receving) Basic Pay / Pay in Pay Band Type

Basic Pay Designation Date of First / Type Comp. Name Name & Address Roster Date of Date of Sl. No. & Office Application Pay in of Status Sl. No S/D/W/O D.D.O. Category Birth Retirement Address (Receving) Pay Flat Band Accounts Officer, 9D & Gr. - II Sister Smt. Anita Biswas B.G. Hospital , 57, 1 1879 9D & B.G. Hospital , 57, Beleghata Main 28/12/2012 21,140 A ALLOTTED Sri Salil Dey Beleghata Main Road, Road, Kolkata - 700 010 Kolkata - 700 010 District Fishery Officer Assistant Director of Bikash Mandal O/O the Deputy Director of Fisheries, Fisheries, Kolkata 2 1891 31/12/2012 22,500 A ALLOTTED Lt. Joydev Mandal Kolkata Zone, 9A, Esplanade East, Kol - Zone, 9A, Esplanade 69 East , Kol - 69 Asstt. Director of Fishery Extn. Officer Fisheries, South 24 Swapan Kr. Saha O/O The Asstt. Director of Fisheries 3 1907 1/1/2013 17,020 A Pgns. New Treasury ALLOTTED Lt. Basanta Saha South 24 Pgs., Alipore, New Treasury Building (6th Floor), Building (6th Floor), Kol - 27 Kol - 27 Eligible for Samapti Garai 'A' Type Assistant Professor Principal, Lady Allotted '' 4 1915 Sri Narayan Chandra 2/1/2013 20,970 A flats but Lady Brabourne College Brabourne College B'' Type Garai willing 'B' Type Flat Staff Nurse Gr. - II Accounts Officer, Lipika Saha 5 1930 S.S.K.M. Hospital , 244, A.J.C. Bose Rd. , 4/1/2013 16,380 A S.S.K.M. Hospital , 244, Allotted Sanjit Kumar Saha Kol -20 A.J.C. Bose Rd. , Kol -20 Basic Pay Designation Date of First / Type Comp. -

A Review on Silver Nanoparticles: Classification, Various Methods Of

water Review A Review on Silver Nanoparticles: Classification, Various Methods of Synthesis, and Their Potential Roles in Biomedical Applications and Water Treatment Muhammad Zahoor 1,* , Nausheen Nazir 1 , Muhammad Iftikhar 1, Sumaira Naz 1, Ivar Zekker 2,*, Juris Burlakovs 3 , Faheem Uddin 4, Abdul Waheed Kamran 5, Anna Kallistova 6, Nikolai Pimenov 6 and Farhat Ali Khan 7 1 Department of Biochemistry, University of Malakand, Chakdara 18800, Pakistan; [email protected] (N.N.); [email protected] (M.I.); [email protected] (S.N.) 2 Faculty of Science, Institute of Chemistry, University of Tartu, 51014 Tartu, Estonia 3 Institute of Forestry and Rural Engineering, Estonian University of Life Sciences, 51006 Tartu, Estonia; [email protected] 4 Department of Electrical Engineering, University of Engineering & Technology, Mardan 23200, Pakistan; [email protected] 5 Department of Chemistry, University of Malakand, Chakdara 18800, Pakistan; [email protected] 6 Research Centre of Biotechnology of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Winogradsky Institute of Microbiology, 119071 Moscow, Russia; [email protected] (A.K.); [email protected] (N.P.) 7 Department of Pharmacy, Shaheed Benazir Bhutto University, Sheringal 18050, Pakistan; [email protected] Citation: Zahoor, M.; Nazir, N.; * Correspondence: [email protected] (M.Z.); [email protected] (I.Z.) Iftikhar, M.; Naz, S.; Zekker, I.; Burlakovs, J.; Uddin, F.; Kamran, A.W.; Kallistova, A.; Pimenov, N.; Abstract: Recent developments in nanoscience have appreciably modified how diseases are pre- et al. A Review on Silver vented, diagnosed, and treated. Metal nanoparticles, specifically silver nanoparticles (AgNPs), are Nanoparticles: Classification, Various widely used in bioscience. From time to time, various synthetic methods for the synthesis of AgNPs Methods of Synthesis, and Their are reported, i.e., physical, chemical, and photochemical ones. -

Group Identity and Civil-Military Relations in India and Pakistan By

Group identity and civil-military relations in India and Pakistan by Brent Scott Williams B.S., United States Military Academy, 2003 M.A., Kansas State University, 2010 M.M.A., Command and General Staff College, 2015 AN ABSTRACT OF A DISSERTATION submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Security Studies College of Arts and Sciences KANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY Manhattan, Kansas 2019 Abstract This dissertation asks why a military gives up power or never takes power when conditions favor a coup d’état in the cases of Pakistan and India. In most cases, civil-military relations literature focuses on civilian control in a democracy or the breakdown of that control. The focus of this research is the opposite: either the returning of civilian control or maintaining civilian control. Moreover, the approach taken in this dissertation is different because it assumes group identity, and the military’s inherent connection to society, determines the civil-military relationship. This dissertation provides a qualitative examination of two states, Pakistan and India, which have significant similarities, and attempts to discern if a group theory of civil-military relations helps to explain the actions of the militaries in both states. Both Pakistan and India inherited their military from the former British Raj. The British divided the British-Indian military into two militaries when Pakistan and India gained Independence. These events provide a solid foundation for a comparative study because both Pakistan’s and India’s militaries came from the same source. Second, the domestic events faced by both states are similar and range from famines to significant defeats in wars, ongoing insurgencies, and various other events. -

Roquiah Sakhawat Hossein1 to Taslima Nasrin

ASIATIC, VOLUME 10, NUMBER 1, JUNE 2016 From Islamic Feminism to Radical Feminism: Roquiah Sakhawat Hossein1 to Taslima Nasrin Niaz Zaman2 Independent University, Bangladesh Abstract This paper examines four women writers who have contributed through their writings and actions to the awakening of women in Bangladesh: Roquiah Sakhawat Hossein, Sufia Kamal, Jahanara Imam and Taslima Nasrin. The first three succeeded in making a space for themselves in the Bangladesh tradition and carved a special niche in Bangladesh. All three of them were writers in different genres – poetry, prose, fiction – with the last best known for her diary about 1971. While these iconic figures contributed towards women’s empowerment or people’s rights in general, Taslima Nasrin is the most radically feminist of the group. However, while her voice largely echoes in the voices of young Bangladeshi women today – often unacknowledged – she has been shunned by her own country. The paper attempts to explain why, while other women writers have also said what Taslima Nasrin has, she alone is ostracised. Keywords Islamic feminism, radical feminism, gynocritics, purdah, 1971, Shahbagh protests In this paper, I wish to examine four women writers who have contributed through their writings and actions to the awakening of women in Bangladesh. Beginning with Roquiah Sakhawat Hossein (1880-1932), I will also discuss the roles played by Sufia Kamal (1911-99), Jahanara Imam (1929-94) and Taslima Nasrin (1962-). The first three succeeded in making a space for themselves in the Bangladesh tradition and carved a special niche in Bangladesh. All three of them were writers: Roquiah wrote poems, short stories, a novel, as well as prose pieces; Sufia Kamal was primarily a poet but also wrote a number of short 1 There is some confusion over the spelling of her name. -

A. Detailed Course Structure of MA (Linguistics)

A. Detailed Course Structure of M.A. (Linguistics) Semester I Course Course Title Status Module & Marks Credits Code LIN 101 Introduction to Core 20(M1)+20(M2)+10(IA) 4 Linguistics LIN 102 Levels of Language Core 20(M1)+20(M2)+10(IA) 4 Study LIN 103 Phonetics Core 20(M1)+20(M2)+10(IA) 4 LIN 104 Basic Morphology & Core 20(M1)+20(M2)+10(IA) 4 Basic Syntax LIN 105 Indo-European Core 20(M1)+20(M2)+10(IA) 4 Linguistics & Schools of Linguistics Semester II LIN 201 Phonology Core 20(M1)+20(M2)+10(IA) 4 LIN 202 Introduction to Core 20(M1)+20(M2)+10(IA) 4 Semantics & Pragmatics LIN 203 Historical Linguistics Core 20(M1)+20(M2)+10(IA) 4 LIN 204 Indo-Aryan Core 20(M1)+20(M2)+10(IA) 4 Linguistics LIN 205 Lexicography Core 20(M1)+20(M2)+10(IA) 4 Semester III LIN 301 Sociolinguistics Core 20(M1)+20(M2)+10(IA) 4 LIN 302 Psycholinguistics Core 20(M1)+20(M2)+10(IA) 4 LIN 303 Old Indo-Aryan Discipline 20(M1)+20(M2)+10(IA) 4 Specific Elective Lin 304 Middle Indo-Aryan Discipline 20(M1)+20(M2)+10(IA) 4 Specific Elective LIN 305 Bengali Linguistics Discipline 20(M1)+20(M2)+10(IA) 4 1 Specific Elective LIN 306 Stylistics Discipline 20(M1)+20(M2)+10(IA) 4 Specific Elective LIN 307 Discourse Analysis Generic 20(M1)+20(M2)+10(IA) 4 Elective Semester IV LIN 401 Advanced Core 20(M1)+20(M2)+10(IA) 4 Morphology & Advanced Syntax LIN 402 Field Methods Core 20(M1)+20(M2)+10(IA) 4 LIN 403 New Indo-Aryan Discipline 20(M1)+20(M2)+10(IA) 4 Specific Elective LIN 404 Language & the Discipline 20(M1)+20(M2)+10(IA) 4 Nation Specific Elective LIN 405 Language Teaching Discipline 20(M1)+20(M2)+10(IA) 4 Specific Elective LIN 406 Term Paper Discipline 50 6 Specific Elective LIN 407 Language Generic 20(M1)+20(M2)+10(IA) 4 Classification & Elective Typology B.