Notes on the High School Reader and Biographical Sketches

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ii TABLE of CONTENTS INVENTORY ENTRY

ii TABLE OF CONTENTS INVENTORY ENTRY ......................................................... iii NOTE ON THE FINDING AID .................................................. iv POLITICAL CAREER ..........................................................4 Town of Westmount .......................................................4 Metropolitan Parks Commission ..............................................8 Miscellaneous Political Activities ..............................................8 ROYAL SOCIETY OF CANADA .................................................9 MANUSCRIPTS ..............................................................9 Archaeology and Anthropology ..............................................9 History and Biography ....................................................11 Novels ................................................................14 Philosophy .............................................................17 Poetry ................................................................19 Political Affairs ..........................................................20 Miscellaneous ..........................................................21 FINANCIAL PAPERS .........................................................22 SUBJECT FILES .............................................................22 PRINTED MATERIAL .........................................................23 MEMORABILIA .............................................................26 CLIPPINGS .................................................................28 APPENDIX -

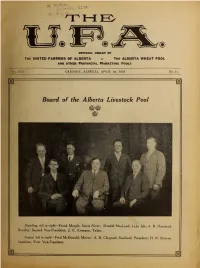

The U.F.A. Who Is Interested in the States Power Trust

M. WcRae, ... pederal, Alta. OFFICIAL ORGAN OF THE UNITED FARMERS OF ALBERTA THE ALBERTA WHEAT POOL AND OTHER PROVINCIAL MARKETING POOLS Vol. VIII. CALGARY, ALBERTA, APRIL 1st, 1929 No. 11. m Board of the Alberta Livestock Pool Standing, left to r/gA/—Frank Marple. Spirit River; Donald MacLeod, Lake Isle; A. B. Haarstad, Bentley. Second Vice-President; J. E, Evenson, Taber. Seated, left to right—Fred McDonald. Mirror; A. B. Claypool, Swalwell. President; H. N. Stearns. Innisfree, First Vice-President. 2 rsw) THE U. F. A. April iBt, lyz^i Ct The Weed-Killing CULTIVATOR with the exclusive Features The Climax Cultivator leads the war on weeds that trob these Provinces of $60,000,000 every year. Put it to work for you! Get the extra profits it is ready to make for you—clean grain, more grain, more money. The Climax has special featxires found in no Sold in Western Canada by other cultivator. Hundreds of owners acclaim it Cockshutt Plow Co., as a durable, dependable modem machine. Limited The Climax is made to suit every type of farm Winnipeg, Regina, and any kind of power. great variety of equip- Saskatoon, Calgary, A Edmonton ment for horses or tractors. Special Features of the Climax Manufactured by The Patented Depth Regulator saves The Frost & Wood Co., Limited pow«r and horse fag. The Power Lift saves time. Points working independ- Smiths Falls, Oat. ently do better work. Heavy Duty Drag Bars equipped with powerful coils prings prevent breakage. Rigid Angle Steel Frame. Variety of points from 2" to 14". llVi" points are standard eqvdpment. -

E Historic Maps and Plans

E Historic Maps and Plans Contains 12 Pages Map 1a: 1771 ‘Plan of the Royal Manor of Richmond’ by Burrell and Richardson. Map 1b: Extract of 1771 ‘Plan of the Royal Manor of Richmond’ by Burrell and Richardson. Map 2. 1837 ‘Royal Gardens, View’ Map 3. 1861-1871 1st Edition Ordnance Survey map Map 4. c.1794 ‘A Plan of Richmond and Kew Gardens’ Map 5. 1844 ‘Sketch plan of the ground attached to the proposed Palm House at Kew and also for the Pleasure Ground - showing the manner in which a National Arboretum may be formed without materially altering the general features’ by Nesfield. Map 6. ‘Royal Botanic Gardens: The dates and extent of successive additions to the Royal Gardens from their foundation in 1760 (9 acres) to the present time (288 acres)’ Illustration 1. 1763 ‘A View of the Lake and Island, with the Orangerie, the Temples of Eolus and Bellona, and the House of Confucius’ by William Marlow Illustration 2. ‘A Perspective View of the Palace from the Northside of the Lake, the Green House and the Temple of Arethusa, in the Royal Gardens at Kew’ by William Woollett Illustration 3. c.1750 ‘A view of the Palace from the Lawn in the Royal Gardens at Kew’ by James Roberts Illustration 4. Great Palm House, Kew Gardens Illustration 5. Undated ‘Kew Palace and Gardens’ May 2018 Proof of Evidence: Historic Environment Kew Curve-PoE_Apps_Final_05-18-AC Chris Blandford Associates Map 1a: 1771 ‘Plan of the Royal Manor of Richmond’ by Burrell and Richardson. Image courtesy of RBGK Archive is plan shows the two royal gardens st before gsta died in 1 and aer eorge had inherited ichmond Kew ardens have been completed by gsta and in ichmond apability rown has relandscaped the park for eorge e high walls of ove ane are still in place dividing the two gardens May 2018 Appendix E AppE-L.indd MAP 1a 1 Map 1b: Extract of 1771 ‘Plan of the Royal Manor of Richmond’ by Burrell and Richardson. -

Gerard Manley Hopkins' Diacritics: a Corpus Based Study

Gerard Manley Hopkins’ Diacritics: A Corpus Based Study by Claire Moore-Cantwell This is my difficulty, what marks to use and when to use them: they are so much needed, and yet so objectionable.1 ~Hopkins 1. Introduction In a letter to his friend Robert Bridges, Hopkins once wrote: “... my apparent licences are counterbalanced, and more, by my strictness. In fact all English verse, except Milton’s, almost, offends me as ‘licentious’. Remember this.”2 The typical view held by modern critics can be seen in James Wimsatt’s 2006 volume, as he begins his discussion of sprung rhythm by saying, “For Hopkins the chief advantage of sprung rhythm lies in its bringing verse rhythms closer to natural speech rhythms than traditional verse systems usually allow.”3 In a later chapter, he also states that “[Hopkins’] stress indicators mark ‘actual stress’ which is both metrical and sense stress, part of linguistic meaning broadly understood to include feeling.” In his 1989 article, Sprung Rhythm, Kiparsky asks the question “Wherein lies [sprung rhythm’s] unique strictness?” In answer to this question, he proposes a system of syllable quantity coupled with a set of metrical rules by which, he claims, all of Hopkins’ verse is metrical, but other conceivable lines are not. This paper is an outgrowth of a larger project (Hayes & Moore-Cantwell in progress) in which Kiparsky’s claims are being analyzed in greater detail. In particular, we believe that Kiparsky’s system overgenerates, allowing too many different possible scansions for each line for it to be entirely falsifiable. The goal of the project is to tighten Kiparsky’s system by taking into account the gradience that can be found in metrical well-formedness, so that while many different scansion of a line may be 1 Letter to Bridges dated 1 April 1885. -

The Poetry Handbook I Read / That John Donne Must Be Taken at Speed : / Which Is All Very Well / Were It Not for the Smell / of His Feet Catechising His Creed.)

Introduction his book is for anyone who wants to read poetry with a better understanding of its craft and technique ; it is also a textbook T and crib for school and undergraduate students facing exams in practical criticism. Teaching the practical criticism of poetry at several universities, and talking to students about their previous teaching, has made me sharply aware of how little consensus there is about the subject. Some teachers do not distinguish practical critic- ism from critical theory, or regard it as a critical theory, to be taught alongside psychoanalytical, feminist, Marxist, and structuralist theor- ies ; others seem to do very little except invite discussion of ‘how it feels’ to read poem x. And as practical criticism (though not always called that) remains compulsory in most English Literature course- work and exams, at school and university, this is an unwelcome state of affairs. For students there are many consequences. Teachers at school and university may contradict one another, and too rarely put the problem of differing viewpoints and frameworks for analysis in perspective ; important aspects of the subject are omitted in the confusion, leaving otherwise more than competent students with little or no idea of what they are being asked to do. How can this be remedied without losing the richness and diversity of thought which, at its best, practical criticism can foster ? What are the basics ? How may they best be taught ? My own answer is that the basics are an understanding of and ability to judge the elements of a poet’s craft. Profoundly different as they are, Chaucer, Shakespeare, Pope, Dickinson, Eliot, Walcott, and Plath could readily converse about the techniques of which they are common masters ; few undergraduates I have encountered know much about metre beyond the terms ‘blank verse’ and ‘iambic pentameter’, much about form beyond ‘couplet’ and ‘sonnet’, or anything about rhyme more complicated than an assertion that two words do or don’t. -

Poetry: Why? Even Though a Poem May Be Short, Most of the Time You Can’T Read It Fast

2.1. Poetry: why? Even though a poem may be short, most of the time you can’t read it fast. It’s like molasses. Or ketchup. With poetry, there are so many things to take into consideration. There is the aspect of how it sounds, of what it means, and often of how it looks. In some circles, there is a certain aversion to poetry. Some consider it outdated, too difficult, or not worth the time. They ask: Why does it take so long to read something so short? Well, yes, it is if you are used to Twitter, or not used to poetry. Think about the connections poetry has to music. Couldn’t you consider some of your favorite lyrics poetry? 2Pac, for example, wrote a book of poetry called The Rose that Grew from Concrete. At many points in history across many cultures, poetry was considered the highest form of expression. Why do people write poetry? Because they want to and because they can… (taking the idea from Federico García Lorca en his poem “Lucía Martínez”: “porquequiero, y porquepuedo”) You ask yourself: Why do I need to read poetry? Because you are going to take the CLEP exam. Once you move beyond that, it will be easier. Some reasons why we write/read poetry: • To become aware • To see things in a different way • To put together a mental jigsaw puzzle • To move the senses • To provoke emotions • To find order 2.2. Poetry: how? If you are not familiar with poetry, you should definitely practice reading some before you take the exam. -

Dactylic Hexameter Is Properly Scanned When Divided Into Six Feet, with Each Foot Labelled a Dactyl Or a Spondee

Latin Meter: an introduction Dactyllic Hexameter English Poetry: Poe’s “The Raven”—Trochaic Octameter / x / x / x / x / x / x / x / x Once up- on a mid- night drear- y, while I pon- dered weak and wear- y / x / x x / x / x x / x / x / x / O- ver man- y a quaint and cur- i- ous vol- ume of for- got- ten lore, / x / x / x / x / x / x / x / x While I nod- ded, near- ly nap- ping, sud- den- ly there came a tap- ping, / x / x / x / x / x / x / x / As of some- one gent- ly rap- ping, rap- ping at my cham- ber door. / x / x / x / x / x / x / x / “’Tis some vis- i- tor,” I mut- tered, “tap- ping at my cham- ber door; / x / x / x / On- ly this, and noth- ing more.” Scansion n Scansion: from the Latin scandere, “to move upward by steps.” Scansion is the science of scanning, of dividing a line of poetry into its constituent parts. n To scan a line of poetry is to follow the rules of scansion by dividing the line into the appropriate number of feet, and indicating the quantity of the syllables within each foot. n A line of dactylic hexameter is properly scanned when divided into six feet, with each foot labelled a dactyl or a spondee. Metrical Symbols: long: – short: u syllaba anceps: u (may be long or short) Basic Feet: dactyl: – u u spondee: – – Dactylic Hexameter: Each line has six feet, of which the first five may be either dactyls or spondees, though the fifth is nearly always a dactyl (– u u), and the sixth must be either a spondee (– –) or a trochee (– u), but we will treat it as a spondee. -

The Phonology of Classical Arabic Meter Chris Golston & Tomas Riad 1

The Phonology of Classical Arabic Meter Chris Golston & Tomas Riad 1. Introduction* Traditional analysis of classical Arabic meter is based on the theory of al-Xalı#l (†c.791 A.D.), the famous lexicographist, grammarian and prosodist. His elaborate circle system remains directly influential in theories of metrics to this day, including the generative analyses of Halle (1966), Maling (1973) and Prince (1989). We argue against this tradition, showing that it hides a number of important generalizations about Arabic meter and violates a number of fundamental principles that regulate metrical structure in meter and in natural language. In its place we propose a new analysis of Arabic meter which draws directly on the iambic nature of the language and is responsible to the metrical data in a way that has not been attempted before. We call our approach Prosodic Metrics and ground it firmly in a restrictive theory of foot typology (Kager 1993a) and constraint satisfaction (Prince & Smolensky 1993). The major points of our analysis of Arabic meter are as follows: 1. Metrical positions are maximally bimoraic. 2. Verse feet are binary. 3. The most popular Arabic meters are iambic. We begin with a presentation of Prosodic Metrics (§2) followed by individual analyses of the Arabic meters (§3). We then turn to the relative popularity of the meters in two large published corpora, relating frequency directly to rhythm (§4). We then argue against al Xalı#l’s analysis as formalized in Prince 1989 (§5) and end with a brief conclusion (§6). 2. Prosodic Metrics We base our theory of meter on the three claims in (1), which we jointly refer to as Binarity. -

The Diary of Heinrich Witt

The Diary of Heinrich Witt Volume 2 Edited by Ulrich Mücke LEIDEN | BOSTON Ulrich Muecke - 9789004307247 Downloaded from Brill.com10/10/2021 09:30:38PM via free access [1] [2] Volume the second Commenced in Lima October the 9th 1867 Tuesday, 24th of January 1843. At 10 Oclock a.m. I started for Mr. Schutte’s silver mine of Orcopampa, my party was rather numerous; it consisted of course of myself on mule back with a led beast for change, the muleteer Delgado, his lad Mateo, both mounted, an Indian guide on foot named Condor, and seven mules laden with various articles for the mine as well as some provisions for myself, two or three fowls, half a sheep, potatoes, bread, salt, and sugar, also some sperm candles, and a metal candlestick. The mules carried each a load from eight to nine arrobes, besides four arrobes the weight of the gear and trappings. I may as well say en passant that I carried the above various articles of food because I had been assured that on this route I should find few eatables. I, accustomed to the ways and habits of the Sierra, saw nothing particular in the costume of my companion, nevertheless I will describe it, the muleteers wore ordinary woollen trowsers, and jackets, a woollen poncho over the shoulders, Chilian boots to the legs, shoes to their feet, but with only a single spur, on the principle that if one side of the animal moved the other could not be left behind; their head covering was a Guayaquil straw hat, underneath it Delgado wore a woollen cap, also round his neck a piece [_] jerga, for the purpose of blind folding his beasts when loading [_] a second piece round his waist the two ends of which [_] [3] and preserved his trowsers. -

2020 Firmamento 03-02-2020.Pdf Page 1 of 244 ESTIMADOS AMIGOS

Somos Firmamento, tan lejano como la excelencia, pero vamos tras ella! TOP ONE SCAPE G.P.Joaquín S. de Anchorena (G1) EXPRESSIVE SMART G.P.Estrellas Mile (G1) Anuario 2020 firmamento 03-02-2020.pdf page 1 of 244 ESTIMADOS AMIGOS Debo decir que estamos muy contentos con la obtención de la Estadística Nacional de Criadores, la Estadística Clásica y la Estadística General de Caballerizas. Todo esto se debe al gran trabajo en equipo que se realiza en Firmamento! 2019 ha sido un año atípico para nosotros, ya que fue un período de transición. Se fue Van Nistelrooy a Chile y finalizamos con nuestra producción de Seattle Fitz, dos padrillos que nos dieron grandes alegrías. Hemos comenzado con otro equipo de entrenadores: Alfredo Gaitán Dassié, junto a sus hijos Nicolás y Lucas con quienes estamos muy satisfechos en un año de adaptación mutua. Al igual que el trabajo perseverante de Adrián Reisenauer en City Bell y de la eficaz tarea de nuestros jockeys Leandro Francisco Fernández Gonçalves y Aníbal Cabrera con el aporte, siempre listo, de Luciano Cabrera. También está nuestro permanente recuerdo y amistad para Carly Etchechoury. En la tradicional gala de los Premios Pellegrini que organiza el Jockey Club, fuimos distinguidos en las categorías: Criador del Año, Caballeriza del Año y nuestro criado Sixties Song, de propiedad de nuestros amigos del Stud Savini, obtuvo la de Campeón Adulto. En todos estos casos, por lo realizado en el año calendario 2018. Sobre este punto, me gustaría resaltar la presentación que Criadores Argentinos realizara ante la Comisión de Carreras de San Isidro, en donde solicitaba se considere unificar con el resto de los principales países del hemisferio sur el cierre de las estadísticas anuales, simultáneamente con el cambio de edad cronológica de nuestras crías, es decir, el 30 de junio. -

03.- Productos Firmamento 2012.P65

20042012 Haras Firmamento Catálogo de Productos Machos Todos los productos incluidos en este Catálogo se encuentran inscriptos en “Carreras de las Estrellas “ GLORIOSO VAN Macho, alazán, nacido el 1ro. de julio de 2010. 1 STORM BIRD STORM CAT TERLINGUA VAN NISTELROOY HALO HALORY COLD REPLY RELAUNCH HONOUR AND GLORY FAIR TO ALL TINA GLORY - 2004 - SKI CHAMP TINA CHAMP Fam. 10. SABATINA 1ra. madre TINA GLORY, por Honour And Glory.- Ganadora en San Isidro a los 3 años, incl. en su debut, hermana materna de TINO WELLS (G1), TINA GLORY (G2) y LO CHAMP (G2). La presente es su primera cría. 2da. madre TINA CHAMP, por Ski Champ.- Ganadora de 4 carreras en San Isidro y La Plata, incl. Clas. Hipódromo de La Plata (G2), Clás. Manuel F. y E. Gnecco (G3), 3ra. Clás. Jockey Club de Rosario (L), hermana materna de BATI CORSA (L) y SHARP PROSPECT (ENG). Madre de: TINO WELLS (m. Poliglote), ganador de 3 carreras en Palermo, a los 2 y 3 años, incl. GP Premio de Honor (G1), Clás. Julio Felix Penna (L), 2do. Clás. Otoño(G2) Clás. Italia (G3), 4to. GP Gral. San Martín (G1). TINA WELLS (h. Poliglote), ganadora de 6 carreras en Palermo a los 3 años, incl. Clás. Abril (G2), Clás. Sibila (G2), Carlos P. Rodriguez (G2), etc. 2da. GP Selección de Potrancas (G1), Clás. Ines Victorica Roca (G3), Clás. Circulo de Propietarios de Caballerizas SPC. (G3) - 2 veces -, Clás. Omega (G3), Clás. Eu- doro J. Balsa (G3), Clás. The Japan Racing Association (L), 3ra. Clás. Carlos Tomkinson (G2), Clás. Inés Victorica Roca (G3), Clás. -

Summerhill Is the Most Unusual School in the World. Here's a Place Where

Summerhill is the most unusual school in the world. Here’s a place where children are not compelled to go to class – they can stay away from lessons for years, if they want to. Yet, strangely enough, the boys and girls in this school LEARN! In fact, being deprived of lessons turns out to be a severe punishment. Summerhill has been run by A. S . Neill for almost forty years. This is the world’s greatest experiment in bestowing unstinted love and approval on children. This is the place, where one courageous man, backed by courageous parents, has had the fortitude to actually apply – without reservation – the principles of freedom and non- repression. The school runs under a true children’s government where the “bosses” are the children themselves. Despite the common belief that such an atmosphere would create a gang of unbridled brats, visitors to Summerhill are struck by the self-imposed discipline of the pupils, by their joyousness, the good manners. These kids exhibit a warmth and lack of suspicion toward adults, which is the wonder, and delight of even official British school investigators. In this book A. S. Neill candidly expresses his unique - and radical – opinions on the important aspects of parenthood and child rearing. These strong commendations of authors and educators attest that every parent who reads this book will find in it many examples of how Neill’s philosophy may be applied to daily life situations. Educators will find Neill’s refreshing viewpoints practical and inspiring. Reading this book is an exceptionally gratifying experience, for it puts into words the deepest feelings of all who care about children, and wish to help them lead happy, fruitful lives.