Thesis from Time and Space: Science Fiction and Its

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Department of English and American Studies Another

Masaryk University Faculty of Arts Department of English and American Studies English Language and Literature & Teaching English Language and Literature for Secondary Schools Bc. Ondřej Harnušek Another Frontier: The Religion of Star Trek Master‘s Diploma Thesis Supervisor: Jeffrey Alan Smith, M.A., Ph. D. 2015 I declare that I have worked on this thesis independently, using only the primary and secondary sources listed in the bibliography. …………………………………………….. Author‘s signature Acknowledgements There are many people, who would deserve my thanks for this work being completed, but I am bound to omit someone unintentionally, for which I deeply apologise in advance. My thanks naturally goes to my family, with whom I used to watch Star Trek every day, for their eternal support and understanding; to my friends, namely and especially to Vítězslav Mareš for proofreading and immense help with the historical background, Miroslav Pilař for proofreading, Viktor Dvořák for suggestions, all the classmates and friends for support and/or suggestions, especially Lenka Pokorná, Kristina Alešová, Petra Grünwaldová, Melanie King, Tereza Pavlíková and Blanka Šustrová for enthusiasm and cheering. I want to thank to all the creators of ―Memory Alpha‖, a wiki-based web-page, which contains truly encyclopaedic information about Star Trek and from which I drew almost all the quantifiable data like numbers of the episodes and their air dates. I also want to thank to Christina M. Luckings for her page of ST transcripts, which was a great help. A huge, sincere thank you goes to Jeff A. Smith, my supervisor, and an endless source of useful materials, suggestions and ideas, which shaped this thesis, and were the primary cause that it was written at all. -

The Us Constitution As Icon

EPSTEIN FINAL2.3.2016 (DO NOT DELETE) 2/3/2016 12:04 PM THE U.S. CONSTITUTION AS ICON: RE-IMAGINING THE SACRED SECULAR IN THE AGE OF USER-CONTROLLED MEDIA Michael M. Epstein* TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION…………………………………………………….. 1 II. CULTURAL ICONS AND THE SACRED SECULAR…………………..... 3 III. THE CAREFULLY ENHANCED CONSTITUTION ON BROADCAST TELEVISION………………………………………………………… 7 IV. THE ICON ON THE INTERNET: UNFILTERED AND RE-IMAGINED….. 14 V. CONCLUSION…………………………………………………….... 25 I. INTRODUCTION Bugs Bunny pretends to be a professor in a vaudeville routine that sings the praises of the United States Constitution.1 Star Trek’s Captain Kirk recites the American Constitution’s Preamble to an assembly of primitive “Yankees” on a far-away planet.2 A groovy Schoolhouse Rock song joyfully tells a story about how the Constitution helped a “brand-new” nation.3 In the * Professor of Law, Southwestern Law School. J.D. Columbia; Ph.D. Michigan (American Culture). Supervising Editor, Journal of International Media and Entertainment Law, and Director, Amicus Project at Southwestern Law School. My thanks to my colleague Michael Frost for reviewing some of this material in progress; and to my past and current student researchers, Melissa Swayze, Nazgole Hashemi, and Melissa Agnetti. 1. Looney Tunes: The U.S. Constitution P.S.A. (Warner Bros. Inc. 1986), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=d5zumFJx950. 2. Star Trek: The Omega Glory (NBC television broadcast Mar. 1, 1968), http://bewiseandknow.com/star-trek-the-omega-glory. 3. Schoolhouse Rock!: The Preamble (ABC television broadcast Nov. 1, 1975), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yHp7sMqPL0g. 1 EPSTEIN FINAL2.3.2016 (DO NOT DELETE) 2/3/2016 12:04 PM 2 SOUTHWESTERN LAW REVIEW [Vol. -

WIF SCIENCE FICTION BIBLIOGRAPHY Compiled by Annabelle Dolidon (Portland State University), Kristi Karathanassis and Andrea King (Huron University College)

WIF SCIENCE FICTION BIBLIOGRAPHY Compiled by Annabelle Dolidon (Portland State University), Kristi Karathanassis and Andrea King (Huron University College) INTRODUCTION In a recent interview for the French newspaper Libération, Roland Lehoucq, president of Les Utopiales (a yearly international SF festival in Nantes) stated that “La SF ne cherche pas à prédire le futur, c’est la question qui importe” (interview with Frédéric Roussel, 19 octobre 2015). Indeed, with plots revolving around space travel, aliens or cyborgs, science fiction (or SF) explores and interrogates issues of borders and colonization, the Other, and the human body. By imagining what will become of us in hundreds or thousands of years, science fiction also debunks present trends in globalization, ethical applications of technology, and social justice. For this reason, science fiction narratives offer a large array of teaching material, although one must be aware of its linguistic challenges for learners of French (see below for more on this subject). In this introduction, we give a very brief history of the genre, focusing on the main subgenres of science fiction and women’s contribution to them. We also offer several suggestions regarding how to teach SF in the classroom – there are additional suggestions for each fictional text referenced in the annotated bibliography. Readers interested in exploring SF further can consult the annotated bibliography, which provides detailed suggestions for further reading. A Brief History of French SF It is difficult to trace the exact contours and origins of science fiction as a genre. If utopia is a subgenre of science fiction, then we can say that the Renaissance marks the birth of science fiction with the publication of Thomas More’s canonical British text Utopia (1516), as well as Cyrano de Bergerac’s Histoire comique des États et Empires de la Lune (circa 1650). -

Star Trek and History

Chapter 15 Who’s the Devil? Species Extinction and Environmentalist Thought in Star Trek Dolly Jørgensen Spock: To hunt a species to extinction is not logical. Dr. Gillian Taylor: Whoever said the human race was logical? —Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home In Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home , the inhabitants of twenty-third-century Earth learn all too well the price of their illogical behavior. By hunting the humpback whale to extinction in the twenty-first century, humankind had sealed its own fate. The humpbacks had been in communication with aliens in the twentieth century, but they had no descendants to reply to an alien probe visiting the planet two centuries later. Earth seemed to be on the verge of destruction, as the seemingly omnipotent probe demanded a reply. Luckily, the Enterprise crew saved the Earth inhabitants from a watery grave with the help of time travel, a biologist, nuclear fuel from a naval vessel, plexiglas, and two twentieth-century whales. Sometimes we think of science fiction as presenting escapist, made-up fantasy worlds. From its beginnings in the 1960s until the present, however, Star Trek has commented on contemporary social issues, establishing itself as part of a larger discourse on the state of the world.1 Contemporary environmental concerns are a major theme in Star Trek. In this chapter, we show how the portrayal of animal species’ extinction in the television shows and movies traces gradual changes in environmentalist thinking over the last forty-five years. Although species extinction could include the mass destruction of worlds and the extinction of peoples, like the loss of the Vulcans in the 2009 movie Star Trek or the civil war that wiped out the population of Cheron (TOS, “Let That Be Your 253 Last Battlefield”), the focus here is on creatures equivalent to animals rather than civilizations that are considered equivalent to humans. -

Star Trek" Mary Jo Deegan University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected]

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by UNL | Libraries University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Sociology Department, Faculty Publications Sociology, Department of 1986 Sexism in Space: The rF eudian Formula in "Star Trek" Mary Jo Deegan University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sociologyfacpub Part of the Family, Life Course, and Society Commons, and the Social Psychology and Interaction Commons Deegan, Mary Jo, "Sexism in Space: The rF eudian Formula in "Star Trek"" (1986). Sociology Department, Faculty Publications. 368. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sociologyfacpub/368 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Sociology, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sociology Department, Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. THIS FILE CONTAINS THE FOLLOWING MATERIALS: Deegan, Mary Jo. 1986. “Sexism in Space: The Freudian Formula in ‘Star Trek.’” Pp. 209-224 in Eros in the Mind’s Eye: Sexuality and the Fantastic in Art and Film, edited by Donald Palumbo. (Contributions to the Study of Science Fiction and Fantasy, No. 21). New York: Greenwood Press. 17 Sexism in Space: The Freudian Formula in IIStar Trek" MARY JO DEEGAN Space, the final frontier. These are the voyages of the starship Enterprise, its five year mission to explore strange new worlds, to seek out new life and new civilizations, to boldly go where no man has gone before. These words, spoken at the beginning of each televised "Star Trek" episode, set the stage for the fan tastic future. -

Manuel De Pedrolo's "Mecanoscrit"

Alambique. Revista académica de ciencia ficción y fantasía / Jornal acadêmico de ficção científica e fantasía Volume 4 Issue 2 Manuel de Pedrolo's "Typescript Article 3 of the Second Origin" Political Wishful Thinking versus the Shape of Things to Come: Manuel de Pedrolo’s "Mecanoscrit" and “Los últimos días” by Àlex and David Pastor Pere Gallardo Torrano Universitat Rovira i Virgili, Tarragona, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/alambique Part of the Comparative Literature Commons, European Languages and Societies Commons, Other Languages, Societies, and Cultures Commons, and the Other Spanish and Portuguese Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Gallardo Torrano, Pere (2017) "Political Wishful Thinking versus the Shape of Things to Come: Manuel de Pedrolo’s "Mecanoscrit" and “Los últimos días” by Àlex and David Pastor," Alambique. Revista académica de ciencia ficción y fantasía / Jornal acadêmico de ficção científica e fantasía: Vol. 4 : Iss. 2 , Article 3. https://www.doi.org/http://dx.doi.org/10.5038/2167-6577.4.2.3 Available at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/alambique/vol4/iss2/3 Authors retain copyright of their material under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 4.0 License. Gallardo Torrano: Catalan Apocalypse: Pedrolo versus the Pastor Brothers The present Catalan cultural and linguistic revival is not a new phenomenon. Catalan language and culture is as old as the better-known Spanish/Castilian is, with which it has shared a part of the Iberian Peninsula for centuries. The 19th century brought about a nationalist revival in many European states, and many stateless nations came into the limelight. -

The Human Adventure Is Just Beginning Visions of the Human Future in Star Trek: the Next Generation

AMERICAN UNIVERSITY HONORS CAPSTONE The Human Adventure is Just Beginning Visions of the Human Future in Star Trek: The Next Generation Christopher M. DiPrima Advisor: Patrick Thaddeus Jackson General University Honors, Spring 2010 Table of Contents Basic Information ........................................................................................................................2 Series.......................................................................................................................................2 Films .......................................................................................................................................2 Introduction ................................................................................................................................3 How to Interpret Star Trek ........................................................................................................ 10 What is Star Trek? ................................................................................................................. 10 The Electro-Treknetic Spectrum ............................................................................................ 11 Utopia Planitia ....................................................................................................................... 12 Future History ....................................................................................................................... 20 Political Theory .................................................................................................................... -

Star Trek and the 1960'S Sung J. Woo English 268 Professor Sawyer April

Star Trek and the 1960's Sung J. Woo English 268 Professor Sawyer April 26, 1993 Star Trek is an important cultural artifact of the Sixties. In the guise of science fiction, the series dealt with substantive concerns such as Vietnam...and civil rights. It explored many of the cultural conflicts of our society by projecting them onto an idealized future.i Not many television shows have accomplished what Star Trek has done. A show that ran for only three seasons, between 1966 and 1969, Star Trek has become a phenomenon of epic proportions. Frank McConnell considers Star Trek a myth: Now that's [Star Trek] what a real mythology is. Not a Joseph Campbell/Bill Moyers discourse...about the proper pronunciation of `Krishna,' but a set of concepts, stories, names, and jokes to fit, and fit us into, the helter-skelter of the quotidian."ii Star Trek survives because it was more than just a television show that made people laugh or cry. It was a show that reached for more, for new ideals and new ideas, for substance. Star Trek indeed is a cultural artifact of the Sixties, and this is readily apparent in many of the episodes. "Let That Be Your Last Battlefield" is a racial parable; "A Taste of Armageddon" is allegorical to Vietnam and war in general; "Turnabout Intruder" deals with women's rights; and "The Paradise Syndrome" and "The Way to Eden" reflects heavily on pop culture. Yet it is important to see that although these episodes mirrored the culture of the Sixties, not all of them were in approval of it. -

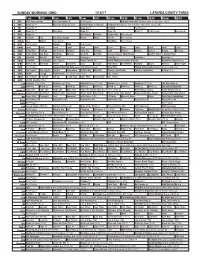

Sunday Morning Grid 1/15/17 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 1/15/17 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program College Basketball Michigan State at Ohio State. (N) Å 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) (TVG) Football Night in America Football Pittsburgh Steelers at Kansas City Chiefs. (10:05) (N) 5 CW News (N) Å News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) News Å Paid Program Eye on L.A. 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Pastor Mike Paid Program 11 FOX In Touch Paid Fox News Sunday Planet Weird DIY Sci Paid Program 13 MyNet Paid Matter Paid Program Best Buys Paid Program 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local 24 KVCR Paint With Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Cook Mexico Martha Hubert Baking Mexican 28 KCET 1001 Nights Bug Bites Bug Bites Edisons Biz Kid$ Biz Kid$ Forever Painless With Miranda Age Fix With Dr. Anthony Youn 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Leverage Å Leverage Å Leverage Å Leverage Å 34 KMEX Conexión En contacto Paid Program Fútbol Central (N) Fútbol Mexicano Primera División República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda John Hagee 46 KFTR Paid Program Escape From New York ››› (1981) Kurt Russell. -

Janet Quarton, 15 Letter Dahl, Cairnbaan, Lochgilphead, Argyll, Scotland

October 1979 NElWSLETXlilR No. 3Z President: Janet Quarton, 15 Letter DaHl, Cairnbaan, Lochgilphead, Argyll, Scotland. Vice President: Sheila Clark, 6 Craigmill Cottages, Strathmartine, by Dundee, Scotland. Committee: Beth Hallam, Flat 3, 36 Clapham Rd, Bedford, England. Sylvia Billings, 49 Southampton Rd, Far Cotton, Northampton, England. Valerie Piacentini, 20 Ardrossan Rd, Saltcoats, Ayrshire, Scotland. Honorary Membersl Gene Roddenberry, Majel Barrett, William Shatner. De Forest Kelley, .rames Doohan, George Takei, Susan Sackett, Grace Lee 'ihitney, Rupert Evans, Senni Cooper, Anne McCaffrey, Anne Page. DUES U.K. - £2.25 per year: Europe, £2.50 surface, £3.00 airmail letter U.S.A. - $11.00 or £4.50 airmail Australia & Japan - £5.00 airmail Hi, folks. We decided to go ahead and put this newsletter out on time even though it is so close to Terracon. It would have been too late if we had left it till after the con and we didn't really fancy going home from the con to the newsletter. As September 30th is the end of STAG's year we have printed the accounts at the end of this letter. He've ended up with less money in the bank than we started with, but don't worry as there is a good reason. Sylvia is still holding renewal money which hasn't been processed through the Gooks yet and a couple of' bookshops owe us quite a lot on zines. Also we'Ve had to layout quite a lot of money for paper and photos to stock up for the con. The clUb has broken even for the year and we have a good stock of 'zines and photos on hand. -

Star Trek STAG NL 28 (STAG Newsletter 28).Pdf

/ April 1978 NEWSLETTER No. 28 President/Secretary, Janet Quarton, 15 Letter Daill, Cairnbaan, Lochgi Iphe ad , hrgyll, Sootland. Vioe PreSident/Editor, Sheila Clark, 6 Craigmill Cottages, Strathmartine, by Dundee, Sootland. Sales Seoretary' Beth Hallam, Flat 3, 36 Clapham Rd, Bedford, England. Membership Seoretary' Sylvia Billings, 49 Southampton Rd, Far Cotton, Northampton, England. Honorary Members> Gene Roddenberry, Mejel Barrett, William Shatner, James Doohan, George Takei, Susan Sackett, Anne MoCaffrey, 1,nne Page. ***************** DUES U.K. £1.50 per year. Europe £2 printed rate, £3.50 idrmail letter rate. U.S.A. ~6.00 l.irmail, ~4.00 surfaoe,' ],ustralia & J~pan, £3 airmail, £2 surface. ***************** Hi, there, I'm sorry this newsletter is a few days late out but I hope you agree that it was worth waiting so that we could give you the latest news from Paramount. It is great to hear, that the go-ahead has finally been given for the movie and that Leonard Nimoy will be back as Spock. SThR TREK just wouldn't have been the same without him. We don't know how things between Leonard and Paramount, etc, were eventually worked out, we are just happy to hear that they have been. 'jle sent out copies of the telegram we received from Gene on Maroh 28th to those of you who sent us S;.Es for info, as we weren't sure how long the newsletter would be delayed. ,Ie guessed you would hear ru:wurs and want confirmation as soon as possible. If any of you want important news as we receive it just send me an SAE and 1'11 file it for later use. -

Medicine in Science Fiction

297 Summer 2011 Editors Doug Davis Gordon College 419 College Drive SFRA Barnesville, GA 30204 A publicationRe of the Scienceview Fiction Research Association [email protected] Jason Embry In this issue Georgia Gwinnett College SFRA Review Business 100 University Center Lane Global Science Fiction.................................................................................................................................2 Lawrenceville, GA 30043 SFRA Business [email protected] There’s No Place Like Home.....................................................................................................................2 Praise and Thanks.........................................................................................................................................4 Nonfiction Editor Conventions, Conferences, SFRA and You...............................................................................................4 ASLE-SFRA Affiliation Update....................................................................................................................5 Michael Klein Executive Committee Business................................................................................................................6 James Madison University MSC 2103 July 2011 Executive Committee Minutes...............................................................................................6 Harrisonburg, VA 22807 SFRA Business Meeting Minutes...........................................................................................................10