5.4. R&D in Basmati Rice Production

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(Pvt) Ltd. Shop No. 01, Ground

Network Position of Exchange Companies and Exchange Companies of 'B' Category As on September 27, 2021 S# Name of Company Address Outlet Type City District Province Remarks Shop No. 01, Ground Floor, Opposite UBL, Mirpur Chowk, 1 Ravi Exchange Company (Pvt) Ltd. Branch Bhimber Bhimber AJK Active Mirpur Road, Bhimber, Azad Jammu & Kashmir Shop No. 01, Plot No. 67, Junaid Plaza, College Road, Near 2 Royal International Exchange Company (Pvt) Ltd. Maqbool Butt Shaheed Chowk, Tehsil Dadyal, Distt. Mirpur Branch Dadyal Dadyal AJK Active Azad Kashmir Office No. 05, Lower Floor, Deen Trade Centre, Shaheed 3 Sky Exchange Company (Pvt) Ltd. Branch Kotli Kotli AJK Active Chowk, Kotli, AJK. Shop # 3&4 Gulistan Plaza Pindi Road Adjacent to NADRA 4 Pakistan Currency Exchange Company (Pvt) Ltd. Branch Kotli Kotli AJK Active off AJK Shop # 1,2,3 Ch Sohbat Ali shopping center near NBP main 5 Pakistan Currency Exchange Company (Pvt) Ltd. Branch Chaksawari Mirpur AJK Active bazar Chaksawari Azad Kashmir Shop No. 119-A/3, Sub Sector C/2, Quaid-e-Azam Chowk, 6 Pakistan Currency Exchange Company (Pvt) Ltd. Branch Dadyal Mirpur AJK Active Mirpur, District Mirpur, Azad Kashmir 7 Dollar East Exchange Company (Pvt.) Ltd. Shop # 39-40, Muhammadi Plaza, Allama Iqbal Road, Mirpur Branch Mirpur Mirpur AJK Active Shop No. 1-A, Ground Floor, Kalyal Building, Naik Alam 8 HBL Currency Exchange (Pvt) Ltd. Branch Mirpur Mirpur AJK Active Road, Chowk Shaheedan, Mirpur, AJK Sector A-5, Opp. NBP Br., Allama Iqbal Road, Mirpur Azad 9 NBP Exchange Company Ltd. Branch Mirpur Mirpur AJK Active Kashmir. -

Estimates of Charged Expenditure and Demands for Grants (Development)

GOVERNMENT OF THE PUNJAB ESTIMATES OF CHARGED EXPENDITURE AND DEMANDS FOR GRANTS (DEVELOPMENT) VOL - II (Fund No. PC12037 – PC12043) FOR 2011 - 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS Demand # Description Pages VOLUME-I PC22036 Development 1 - 720 VOLUME-II PC12037 Irrigation Works 1 - 40 PC12038 Agricultural Improvement and Research 41 - 45 PC12040 Town Development 47 - 52 PC12041 Roads and Bridges 53 - 171 PC12042 Government Buildings 173 - 399 PC12043 Loans to Municipalities / Autonomous Bodies, etc. 401 - 411 GOVERNMENT OF THE PUNJAB GENERAL ABSTRACT OF DISBURSEMENT (GROSS) (Amount in million) Budget Revised Budget Estimates Estimates Estimates 2010-2011 2010-2011 2011-2012 PC22036 Development 100,099.054 81,431.616 127,207.412 PC12037 Irrigation Works 10,638.747 8,071.528 10,891.000 PC12038 Agricultural Improvement and Research 145.865 146.554 124.087 PC12040 Town Development 650.000 287.491 1,200.000 PC12041 Roads and Bridges 49,781.208 37,985.865 38,251.976 PC12042 Government Buildings 34,700.126 10,844.478 42,325.525 PC12043 Loans to Municipalities/Autonomous Bodies etc. 11,531.739 8,468.178 10,987.138 TOTAL :- 207,546.739 147,235.710 230,987.138 Current / Capital Expenditure detailed below: Daanish School System (3,000.000) - (3,000.000) Punjab Education Endowment Fund (PEEF) - - (2,000.000) Punjab Education Foundation (PEF) - - (6,000.000) TEVTA - - (2,000.000) DLIs for MDGs - - (8,500.000) Town Development (650.000) (287.491) (1,200.000) Population Welfare Programme (1,865.000) (1,341.127) (2,860.000) Companies: FIEDMC, PLDC, SWM, PLDDB, - - (6,440.000) PARB etc Current Capital Expenditure (11,531.739) (8,468.178) (10,987.138) Total (17,046.739) (10,096.796) (42,987.138) Net Annual Development Programme 190,500.000 137,138.914 188,000.000 BUDGET ESTIMATES REVISED ESTIMATES BUDGET ESTIMATES Page # GRANT/SECTOR/SUBSECTOR 2010‐11 2010‐11 2011‐12 SUMMARY Rs Rs Rs. -

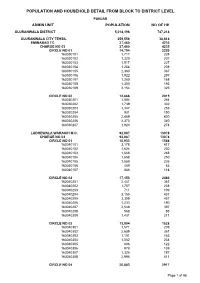

Gujranwala Blockwise

POPULATION AND HOUSEHOLD DETAIL FROM BLOCK TO DISTRICT LEVEL PUNJAB ADMIN UNIT POPULATION NO OF HH GUJRANWALA DISTRICT 5,014,196 747,214 GUJRANWALA CITY TEHSIL 259,556 38,614 EMINABAD TC 27,460 4235 CHARGE NO 03 27,460 4235 CIRCLE NO 01 14,794 2220 163030101 1,717 224 163030102 1,320 207 163030103 1,517 227 163030104 1,254 208 163030105 2,360 367 163030106 1,922 297 163030107 1,250 168 163030108 1,300 193 163030109 2,154 329 CIRCLE NO 02 12,666 2015 163030201 1,884 264 163030202 1,739 302 163030203 1,347 255 163030204 931 150 163030205 2,469 430 163030206 2,373 340 163030207 1,923 274 LUDHEWALA WARAICH M.C. 92,087 13078 CHARGE NO 04 92,087 13078 CIRCLE NO 01 10,933 1548 163040101 3,178 417 163040102 1,624 230 163040103 1,668 248 163040104 1,658 250 163040105 1,550 226 163040106 409 63 163040107 846 114 CIRCLE NO 02 17,153 2480 163040201 2,441 361 163040202 1,757 238 163040203 711 109 163040204 3,155 431 163040205 3,309 457 163040206 1,233 190 163040207 2,548 397 163040208 568 86 163040209 1,431 211 CIRCLE NO 03 13,094 1828 163040301 1,571 209 163040302 2,685 361 163040303 1,101 165 163040304 1,552 234 163040305 886 122 163040306 978 139 163040307 1,325 187 163040308 2,996 411 CIRCLE NO 04 20,883 2917 Page 1 of 98 POPULATION AND HOUSEHOLD DETAIL FROM BLOCK TO DISTRICT LEVEL PUNJAB ADMIN UNIT POPULATION NO OF HH 163040401 2,874 411 163040402 2,373 320 163040403 2,942 422 163040404 2,699 354 163040405 1,693 282 163040406 2,405 319 163040407 1,983 300 163040408 1,722 225 163040409 2,192 284 CIRCLE NO 05 18,888 2742 163040501 2,002 283 163040502 -

Women's Health Project

Completion Report Project Number: 27037 Loan Number: 1671 November 2007 Pakistan: Women’s Health Project CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS Currency Unit – Pakistan rupee/s (PRe/PRs) At Appraisal At Project Completion (February 1999) (December 2006) PRe1.00 = $0.0195 $0.0160 $1.00 = PRs51.30 PRs60.88 For cost comparison in this report, local currency costs were converted to US dollars at the rate prevailing at the time of each transaction. ABBREVIATIONS ADB – Asian Development Bank BCC – behavior change communication BHU – basic health unit BME – benefit monitoring and evaluation CWD – Communication and Works Department DHMT – district health management team DHQ – district headquarters DOH – Department of Health EA – executing agency EDO – executive district officer EmOC – emergency obstetric care IEC – information, education, and communication LHV – lady health visitor LHW – lady health worker MCH – maternal and child health MMR – maternal mortality rate MNCH – maternal, neonatal, and child health MOH – Ministry of Health NGO – nongovernment organization NWFP – North-West Frontier Province OPEC – Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries PCR – project completion review PCU – project coordination unit PHN – public health nurse PSC – project steering committee RHC – rural health center RRP – report and recommendation of the President SAP – Social Action Program SDR – special drawing rights TA – technical assistance TBA – traditional birth attendant THQ – tehsil (subdistrict) headquarters TT – tetanus toxoid NOTES (i) The fiscal year (FY) of the Government of Pakistan and the provincial governments ends on 30 June. “FY” before a calendar year denotes the year in which the fiscal year ends, e.g., FY2007 ends on 30 June 2007. (ii) In this report, “$” refers to US dollars. Vice President L. -

ASKAR OIL SERVICES (PVT) LTD APPLICABLE RETAIL PRICE of MS & HSD at PETROL PUMPS EFFECTIVE from 1St AUGUST-2021

ASKAR OIL SERVICES (PVT) LTD APPLICABLE RETAIL PRICE OF MS & HSD AT PETROL PUMPS EFFECTIVE FROM 1st AUGUST-2021 Retail Price of Sr # Name of Civil District Province Petrol Pump City/Location S.F Amount HSD MS 1 ABBOTTABAD KP Sarfraz Filling Station (MSK) At 15 K.M From Jaika Gali ,On Barot Jhika Gali Road at Barot, 0.6936 117.22 120.49 2 ABBOTTABAD KP Kunhar Vally Filling Station At Village Boi, On Boi-Garhi Habib Ullah Road, 1.5307 118.06 121.33 At Mouza Khoda, On Rawalpindi – Hasanabdal – Peshawar Road National Highway (N-5), At 3 ATTOCK Punjab ALI F/S 0.3456 116.88 120.15 6.7 KM from Burhan Interchange, in Khasra No.398, Tehsil HASANABDAL District ATTOCK At Mouza & Village Lakar Mar, On Jand / Mukhad Road, Khasra No.4568, Khatooni No. 01, 4 ATTOCK Punjab KHATTAK P/S 0.3923 116.92 120.19 Khewat No 1811, Tehsil JAND District ATTOCK 5 ATTOCK Punjab PetrogasCNG Station GT Rd, Burhan 0.5159 117.05 120.32 6 BADIN Sind NADEEM & CO. At Badin Town, Plot No. 10-B, 10-C, At Deh Sonhar, On Golarchi Road, Taluka & Distt. Badin 1.1594 117.69 120.96 At Plot No.197/4, At Deh Barodari, in B/W 0-1 from Golarchi, On Golarchi – Garhore 7 BADIN Sind Seven Star P/S 1.0541 117.58 120.85 Sharif Road, Taluka Shaheed Fazil Rahu, District BADIN. At Deh & Tapo Walhar, in B/w 13 -14km, On Talhar / Badin Road, At Peeru Lashari, 8 BADIN Sind Al-Murtaza P/S 1.3176 117.85 121.12 Taluka Talhar, District Badin. -

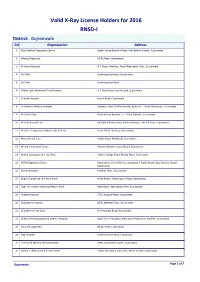

Valid X-Ray License Holders for 2016 RNSD-I

Valid X-Ray License Holders for 2016 RNSD-I District: Gujranwala Sr# Organization Address 1 Alaq Medical Diagnostic Centre Green House Kashmir Road, Alah Bakhsh Colony, Gujranwala 2 Alfalaq Diagnostic 10-Dc Road, Gujranwala 3 Al-Ghani Hospital G.T. Road, Ghakhar, Tehsil Wazirabad, Distt. Gujranwala 4 Ali Clinic Commissioner Road, Gujranwala 5 Ali Clinic Commissioner Road 6 Allama Iqbal Memorial Trust Hospital G.T. Road Near Chan Da Qila, Gujranwala 7 Al-Raee Hospital Jinnah Road, Gujranwala 8 Al-Rehman Medical Complex Maulana Zafar Ali Khan Chowk, By Pass G.T Road Wazirabad, Gujranwala 9 Al-Shafi X-Ray Khan Ikhwan Market, G.T. Road, Rahwali, Gujranwala 10 Al-Shifa X-ray & Lab Mohalla Bakhtey Wala, Kacha Darwaza, Tehsil & Distt. Gujranwala 11 Al-Tahir Computerized Micro Lab. & X-ray Beron Khiali Darwaza, Gujranwala 12 Aman Dental Care Sialkot Road, Khokherki, Gujranwala 13 Anjum Ultrasound Centre Muneer Chowk Hospital Road, Gujranwala 14 Anmol Laboratory & X-ray Clinic Islamia College Road, Bhutta Plaza, Gujranwala 15 ARSH Diagnostic Centre Gujranwala-Sialkot By Pass, Kangniwala Pepli Chowk, Opp Sanitary Chowk, Gujranwala 16 Ashraf Hospital Satellite Town, Gujranwala 17 Bright Clinical Lab. & X-ray Centre Khiali Addah, Sheikhupura Road, Gujranwala 18 Capt. Dr. Arshad Mahmood Nasim Clinic Main Bazar, Wazirabad, Distt. Gujranwala 19 Chattha Hospital 27/1, Hospital Road, Gujranwala 20 Chaudhary Hospital 28-D, Satellite Town, Gujranwala 21 Chaudhary X-ray Clinic Civil Hospital Road, Gujranwala 22 Cheema Heart Complex & General Hospital Main Zia-ul-Haq Road, Near Lords Hotel, Dist. Katcher, Gujranwala 23 Citi Care Diagnostic 28-DC Road, Gujranwala 24 City Hospital Commissioner Road, Gujranwala 25 Combined Military Hospital (CMH) CMH, Gujranwala Cantt., Gujranwala 26 Doctor’s Ultrasound & X-Ray Center 3-Bara Dari Road, Civil Lines, Munir Chowk, Gujranwala Gujranwala Page 1 of 3 27 Dr. -

Pak Pos and RMS Offices 3Rd Ed 1962

Instructions for Sorting Clerks and Sorters ARTICLES ADDRl!SSBD TO TWO PosT-TOWNS.-If the address Dead Letter Offices receiving articles of the description re 01(an article contains the names of two post-town, the article ferred in this clause shall be guided by these instructions so far should, as a general rule, be forwarded to whichever of the two as the circumstances of each case admit of their application. towns is named last unless the last post-town- Officers employed in Dead Letter Offices are selected for their special fitness for the work and are expected to exercise intelli ( a) is obviously meant to indicate the district, in which gence and discretion in the disposal of articles received by case the article should be . forwar ~ ed ~ · :, the first them. named post-town, e. g.- A. K. Malik, Nowshera, Pes!iaivar. 3. ARTICLES ADDRESSED TO A TERRITORIAL DIVISION WITH (b) is intended merely as a guide to the locality, in which OUT THE ADDITION OF A PosT-TOWN.-If an article is addressed case the article should be forwarded to the first to one of the provinces, districts, or other territorial divisions named post-town, e. g.- mentioned in Appendix I and the address does not contain the name of any post-town, it should be forwarded to the post-town A. U. Khan, Khanpur, Bahawalpur. mentioned opposite, with the exception of articles addressed to (c) Case in which the first-named post-town forms a a military command which are to be sent to its headquarters. component part of the addressee's designation come under the general rule, e. -

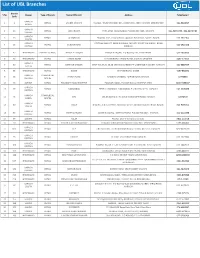

To Download UBL Branch List

List of UBL Branches Branch S No Region Type of Branch Name Of Branch Address Telephone # Code KARACHI 1 2 RETAIL LANDHI KARACHI H-G/9-D, TRUST CERAMIC IND., LANDHI IND. AREA KARACHI (EPZ) EXPORT 021-5018697 NORTH KARACHI 2 19 RETAIL JODIA BAZAR PARA LANE, JODIA BAZAR, P.O.BOX NO.4627, KARACHI. 021-32434679 , 021-32439484 CENTRAL KARACHI 3 23 RETAIL AL-HAROON Shop No. 39/1, Ground Floor, Opposite BVS School, Sadder, Karachi 021-2727106 SOUTH KARACHI CENTRAL BANK OF INDIA BUILDING, OPP CITY COURT,MA JINNAH ROAD 4 25 RETAIL BUNDER ROAD 021-2623128 CENTRAL KARACHI. 5 47 HYDERABAD AMEEN - ISLAMIC PRINCE ALLY ROAD PRINCE ALI ROAD, P.O.BOX NO.131, HYDERABAD. 022-2633606 6 46 HYDERABAD RETAIL TANDO ADAM STATION ROAD TANDO ADAM, DISTRICT SANGHAR. 0235-574313 KARACHI 7 52 RETAIL DEFENCE GARDEN SHOP NO.29,30, 35,36 DEFENCE GARDEN PH-1 DEFENCE H.SOCIETY KARACHI 021-5888434 SOUTH 8 55 HYDERABAD RETAIL BADIN STATION ROAD, BADIN. 0297-861871 KARACHI COMMERCIAL 9 65 NAPIER ROAD KASSIM CHAMBERS, NAPIER ROAD,KARACHI. 32775993 CENTRAL CENTRE 10 66 SUKKUR RETAIL FOUJDARY ROAD KHAIRPUR FOAJDARI ROAD, P.O.BOX NO.14, KHAIRPUR MIRS. 0243-9280047 KARACHI 11 69 RETAIL NAZIMABAD FIRST CHOWRANGI, NAZIMABAD, P.O.BOX NO.2135, KARACHI. 021-6608288 CENTRAL KARACHI COMMERCIAL 12 71 SITE UBL BUILDING S.I.T.E.AREA MANGHOPIR ROAD, KARACHI 32570719 NORTH CENTRE KARACHI 13 80 RETAIL VAULT Shop No. 2, Ground Floor, Nonwhite Center Abdullah Harpoon Road, Karachi. 021-9205312 SOUTH KARACHI 14 85 RETAIL MARRIOT ROAD GILANI BUILDING, MARRIOT ROAD, P.O.BOX NO.5037, KARACHI. -

Sr # Outlet Name Location Address 1 Super Shaheen Umerkot Umerkot 2

Sr # Outlet Name Location Address 1 Super Shaheen Umerkot Umerkot 2 Mukhi Thana Bola Khan Thana Bola Khan 3 A Rahim Sethio Tando Muhammad Khan Sijawal Road Tando Muhammad Khan 4 Bilal Tando Jan Muhammad Tando Jan Muhammad 5 Huziafa Tando Haider Tando Haider 6 Sattar Tando Allahyar Tando Allahyar 7 Imran Tando Adam Tando Adam 8 Habib Sehwan Indus Highway Sehwan 9 PSO S/S 09 Sanghar Tando Adam Road Sanghar 10 Dahri Sakrand Sakrand 11 Jam P/S Qazi Ahmed Qazi Ahmed 12 Qarni Odero Lal Odero Lal 13 Nawabshah Nawabshah Sakrand Road Nawabshah 14 Nasir Mujeeb Nawabshah Sanghar Road Nawabshah 15 Razi Shah Naukot Naukot 16 H Misri Shah Nasarpur Tando Allahyar Roead Nasarpur 17 Jamali Moro Moro 18 Malani Mithi Mithi 19 Shaikh Mirpurkhas Mirpurkhas 20 Nadir Mehar Indus Highway Mehar 21 Shaheed Ismail Matli Badin Road Matli 22 Al Ahmed Matiari NHW Matiari 23 New Abideen Kunri Kunri 24 Diaram Kot Ghulam Muhammad Kot Ghulam Muhammad 25 Nathan Shah KN Shah Indus Highway KN Shah 26 Samo F/S Khyber NHW Khyber 27 Baloch Khorwah Khorwah 28 Mehran Khipro Khipro 29 Al Amin Khanot Indus Highway Khanot 30 Jamali Johi Johi 31 New Razi Shah Islamkot Islamkot 32 Golden Taj Hyderabad Old Sabzi Mandi Hyderabad 33 Platinum Hyderabad Old NHW Hyderabad 34 Hala Hala Hala 35 Gharib Nawaz Daur Daur 36 Carwan e Afandi Dadu Dadu 37 Sikander Dadu Dadu 38 Paras Chachro Chachro 39 Amir Birmani Bhan Syedabad Indus Highway Bhan Syedabad 40 Sadat Badin Badin 41 Shahbaz 1 PS Sukkur Main Bus Stand Sukkur 42 AWT SS Sukkur Ayub Gate Sukkur 43 Rohri PS Rohri Main National Highway, Rohri -

Defaulted Disconnected Industrial and Commercial Consumers As on July-2021 Having Arrears Exceeding Rupees One Million Sr

SNGPL Defaulted Disconnected Industrial and Commercial Consumers as on July-2021 Having Arrears exceeding Rupees one Million Sr. Aging in Category Region Account ID Name Address Tariff No. Total Arrears (Rs.) Months FACTORY 510 PECO ROAD KOT LAKHPAT 1 IND LHR-E 1089641000 M/S Tariq Aziz Box LAHORE General Ind. 2,193,435,290 99 2 IND-LNG MLT 4530920000 M/S D G Khan Cement Co LTD KUFLA SATAI DERA GHAZI KHAN Captive Power 1,848,222,490 5 3 IND SKP 2467051000 M/S Yaqoob Steel 32 KM SHEIKHUPURA RD SHEIKHUPURA General Ind. 766,264,481 97 103 FAZA ROAD ST JOHN PARK LAHORE 4 IND SKP 5847051000 M/S Flying Paper Inds CANTT General Ind. 710,207,165 114 12 KM SHEIKHUPURA ROAD LIBERTY 5 COM SKP 9286282000 M/S A W S Traders TOWN SHAHDARA COM 670,774,859 98 M/S VALUE FUELS C N G FILLING STATION 6 IND SGD 9571311000 Abdul Qayyum Khan Co MULTAN ROAD NR PAF BASE MIANWALI CNG 540,776,744 96 7 IND PSH 0390873000 M/S Bismillah Corporation I E KOHAT ROAD PESHAWAR General Ind. 462,748,437 41 8 IND-LNG FBD 7173590000 M/S Amtex Private Limited JARANWALA ROAD KHURRIANWALA Captive Textile 441,188,055 46 PROCESSING NR CENTURY PAPER 9 IND LHR-E 6110741000 M/S Novelty Fabrics JAMBER DISTT KASUR Textile 377,503,511 147 LTD (CAPATIVE POWER) 64-KM MULTAN 10 IND-LNG LHR-E 4923438213 M/S KARAM-E-KAREEM SPINNINGROAD MILLS BHAI (PVT) PHERU LTD DISTT KASUR Captive Textile 373,925,433 12 VILLAGE SHAGONAKA OPOSITE BANDA 11 IND MRD 2982315248 M/S. -

Sr# Name Firm Name City Address Ph# Mob# Email 1 MIAN GULZAR AHMED ZAM ZAM SILK FACTORY 2 MR

Sr# Name Firm Name City Address Ph# Mob# Email 1 MIAN GULZAR AHMED ZAM ZAM SILK FACTORY 2 MR. INAYAT ULLAH KAPOOR MOON STEAM BONE MILLS Wazirabad AHMAD NAGAR ROAD 055-6600146 0300-8620946 [email protected] 3 MR. MOHAMMAD ASIM BUTT RACHNA AGRI BUSINESS Gujranwala RACHNA COMPLEX SHEIKHUPURA ROAD 055-4803051-57 0300-8642253 [email protected] 4 MR. RANA FAHAD MUSHTAQ MODERN RICE & GENERAL MILLS Gujranwala MANDIALA TEGA ROAD FEROZEWALA 055-43840298 0300-8644801 [email protected] 5 MR. FAISAL RAUF NASQ INTERNATIONAL (PVT) LTD 6 MIRZA AURANGZEB MIRZA RICE MILLS (PVT) LTD. Gujranwala 5 KM GUJRANWALA ROAD, ALI PUR CHATTHA 055-6332614 0333-8281000 [email protected] 7 KHAWAJA BILAL AHMED AGROMAN CRYSTAL RICE MILLS (PVT) LTD Gujranwala QADIRABAD ROAD ALI PUR CHATTHA 055-6333865 0300-4137538 [email protected] 8 MIAN SHAHID HUSSAIN TARAR GALAXY RICE MILLS (PVT) LTD Gujranwala WAHNDO ROAD, EMINABAD 055-3264184 0300-8740881 [email protected] 9 MALIK MUHAMMAD JAHENGIR WHITE PEARL RICE MILLS LTD Hafizabad SOLGIN KHARL JALAL PUR BHATTIAN 7500022-33-44 0321-8404955 [email protected] 10 MUHAMMAD SALEEM FARRUKH SATTAR & COMPANY Hafizabad GHALLA MANDI JALAL PUR BHATTIAN TEH. PINDI BHATTIAN 054-7500187 0321-6526271 11 SANA ANWAR GREEN GOLD SEED INDUSTRIES (PVT) LTD Gujranwala 6-MINI STADIUM SHEIKHUPURA ROAD 4223542-43 12 ABDUL RAZAQ MUSLIM RICE TRADERS Gujranwala 129-SIE #2 0553844617 0321-6273747 [email protected] 13 LUBNA SAJJAD RANA AHSAN CHICKS Gujranwala 561 GALI KASHMIRIAN WALI AHSAN CHICKS 055-38664476 0300-8644838 14 ARSHAD IQBAL WAHLA RICE MILLS (PVT) LTD Gujranwala G.T. ROAD GHAKKHAR MANDI 3881825 0300-8740923 15 KH. -

Board of Intermediate & Secondary Education, Gujranwala Codewise

Board of Intermediate & Secondary Education, Gujranwala Codewise list of institutes(Schools/Colleges/Higher Secondary Schools) for online system Code Name 1 111001 GOVT. HIGH SCHOOL, AHMAD NAGAR (GUJRANWALA) 111002 GOVT. HIGH SCHOOL, ALI PUR CHATHA (GUJRANWALA) 111003 GOVT. HIGH SCHOOL, ABDAL (GUJRANWALA) 111004 GOVT. HIGH SCHOOL, AROOP (GUJRANWALA) 111005 GOVT. HIGH SCHOOL, ATTAWA (GUJRANWALA) 111006 GOVT. HIGH SCHOOL, AKBAR GHANOKE (GUJRANWALA) 111007 GOVT. CO-OP HIGH SCHOOL BUDHA GORAYA (GUJRANWALA) 111008 GOVT. HIGH SCHOOL, BALLEYWALA (GUJRANWALA) 111009 GOVT. HIGH SCHOOL BHIRI KHURD (GUJRANWALA) 111010 GOVT. HIGH SCHOOL BHAROKE CHEEMA (GUJRANWALA) 111011 GOVT. HIGH SCHOOL BHATTI BHANGO (GUJRANWALA) 111012 GOVT. HIGH SCHOOL BABBAR (GUJRANWALA) 111013 GOVT. HIGH SCHOOL BOTALA SHARM SINGH (GUJRANWALA) 111014 GOVT. HIGH SCHOOL BUTALA JHANDA SINGH (GUJRANWALA) 111015 GOVT. HIGH SCHOOL CHAHAL KALAN (GUJRANWALA) 111016 GOVT. HIGH SCHOOL CHAK BAIG (GUJRANWALA) 111017 GOVT. HIGH SCHOOL, CHANDALA (GUJRANWALA) 111018 GOVT. HIGH SCHOOL DHAUNKAL (GUJRANWALA) 111019 GOVT. HIGH SCHOOL DHENSAR PAEEN (GUJRANWALA) 111020 GOVT. HIGH SCHOOL DANDIAN (GUJRANWALA) 111021 GOVT. HIGH SCHOOL DOGRANWALA WARAICH (GUJRANWALA) 111022 GOVT. HIGH SCHOOL DHILLANWALI (GUJRANWALA) 111023 GOVT. ISLAMIA HIGH SCHOOL NO.1 EMINABAD (GUJRANWALA) 111024 GOVT. ISLAMIA HIGH SCHOOL NO.2 EMINABAD (GUJRANWALA) 111025 GOVT. J.M. ISLAMIA HIGH SCHOOL FEROZEWALA (GUJRANWALA) 111026 GOVT. HIGH SCHOOL NO.1 GHAKHAR (GUJRANWALA) 111027 GOVT. HIGH SCHOOL NO.2 GHAKHAR (GUJRANWALA) 111028 GOVT. HIGH SCHOOL GUNNA AUR (GUJRANWALA) 111029 GOVT. HIGH SCHOOL GARMULA VIRKAN (GUJRANWALA) 111030 GOVT. HIGH SCHOOL HERDO RATALI (GUJRANWALA) 111031 GOVT. HIGH SCHOOL VERPAL (GUJRANWALA) 111032 GOVT. HIGH SCHOOL HAZRAT KAILIANWALA (GUJRANWALA) 111033 GOVT. HIGH SCHOOL HAMID PUR KALAN (GUJRANWALA) 111034 GOVT. HIGH SCHOOL JAMKE CHATHA (GUJRANWALA) 111035 GOVT.