Masterworks from the Collection of Tobia and Morton Mower March 31

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TEL AVIV PANTONE 425U Gris PANTONE 653C Bleu Bleu PANTONE 653 C

ART MODERNE ET CONTEMPORAIN TRIPLEX PARIS - NEW YORK TEL AVIV Bleu PANTONE 653 C Gris PANTONE 425 U Bleu PANTONE 653 C Gris PANTONE 425 U ART MODERNE et CONTEMPORAIN Ecole de Paris Tableaux, dessins et sculptures Le Mardi 19 Juin 2012 à 19h. 5, Avenue d’Eylau 75116 Paris Expositions privées: Lundi 18 juin de 10 h. à 18h. Mardi 19 juin de 10h. à 15h. 5, Avenue d’ Eylau 75116 Paris Expert pour les tableaux: Cécile RITZENTHALER Tel: +33 (0) 6 85 07 00 36 [email protected] Assistée d’Alix PIGNON-HERIARD Tel: +33 (0) 1 47 27 76 72 Fax: 33 (0) 1 47 27 70 89 [email protected] EXPERTISES SUR RDV ESTIMATIONS CONDITIONS REPORTS ORDRES D’ACHAt RESERVATION DE PLACES Catalogue en ligne sur notre site www.millon-associes.com בס’’ד MODERN AND CONTEMPORARY FINE ART NEW YORK : Tuesday, June 19, 2012 1 pm TEL AV IV : Tuesday, 19 June 2012 20:00 PARIS : Mardi, 19 Juin 2012 19h AUCTION MATSART USA 444 W. 55th St. New York, NY 10019 PREVIEW IN NEW YORK 444 W. 55th St. New York, NY. 10019 tel. +1-347-705-9820 Thursday June 14 6-8 pm opening reception Friday June 15 11 am – 5 pm Saturday June 16 closed Sunday June 17 11 am – 5 pm Monday June 18 11 am – 5 pm Other times by appointment: 1 347 705 9820 PREVIEW AND SALES ROOM IN TEL AVIV 15 Frishman St., Tel Aviv +972-2-6251049 Thursday June 14 6-10 pm opening reception Friday June 15 11 am – 3 pm Saturday June 16 closed Sunday June 17 11 am – 6 pm Monday June 18 11 am – 6 pm tuesday June 19 (auction day) 11 am – 2 pm Bleu PREVIEW ANDPANTONE 653 C SALES ROOM IN PARIS Gris 5, avenuePANTONE d’Eylau, 425 U 75016 Paris Monday 18 June 10 am – 6 pm tuesday 19 June 10 am – 3 pm live Auction 123 will be held simultaneously bid worldwide and selected items will be exhibited www.artonline.com at each of three locations as noted in the catalog. -

ACCADEMIA FINE ART Monaco Auction

ACCADEMIA FINE ART Monaco Auction Par le Ministère de Organisation & Direction générale Me M.-Th. Escaut-Marquet, Huissier à Monaco Joël GIRARDI Vente aux enchères publiques à l’Hôtel de Paris, Monte-Carlo Gestion et organisation générale Salons Bosio - Beaumarchais François Xavier VANDERBORGHT Vente menée par Serge HUTRY Directeur du département Bijoux Fethia EL MAY Diplômée de l’Institut National de Gemmologie Relation publique Samedi 22 Juin 2013 à 16h30 Alessandra TESTA Exposition publique Photographe Jeudi 20 et Vendredi 21 Juin de 10h à 20h Marcel LOLI Samedi 22 Juin de 10h à 14h Retrait des lots à l’Hôtel de Paris Dimanche 23 Juin 2013 Accademia Fine Art ouvre l’ère des enchères virtuelles : grace à Artfact Live, vous avez la possibilité de suivre en direct la vente et d’enchérir en direct sur internet pendant nos ventes. 2 3 ACCADEMIA FINE ART Monaco Auction Par le Ministère de Organisation & Direction générale Me M.-Th. Escaut-Marquet, Huissier à Monaco Joël GIRARDI Vente aux enchères publiques à l’Hôtel de Paris, Monte-Carlo Gestion et organisation générale Salons Bosio - Beaumarchais François Xavier VANDERBORGHT Vente menée par Serge HUTRY Directeur du département Bijoux Fethia EL MAY Diplômée de l’Institut National de Gemmologie Relation publique Samedi 22 Juin 2013 à 16h30 Alessandra TESTA Exposition publique Photographe Jeudi 20 et Vendredi 21 Juin de 10h à 20h Marcel LOLI Samedi 22 Juin de 10h à 14h Retrait des lots à l’Hôtel de Paris Dimanche 23 Juin 2013 Accademia Fine Art ouvre l’ère des enchères virtuelles : grace à Artfact Live, vous avez la possibilité de suivre en direct la vente et d’enchérir en direct sur internet pendant nos ventes. -

Monet and American Impressionism

Harn Museum of Art Educator Resource Monet & Impressionism About the Artist Claude Monet was born in Paris on November 14, 1840. He enjoyed drawing lessons in school and began making and selling caricatures at age seventeen. In 1858, he met landscape artist Eugène Boudin (1824-1898) who introduced him to plein-air (outdoor) painting. During the 1860s, only a few of Monet’s paintings were accepted for exhibition in the prestigious annual exhibitions known as the Salons. This rejection led him to join with other Claude Monet, 1899 artists to form an independent group, later known as the Impressionists. Photo by Nadar During the 1860s and 1870s, Monet developed his technique of using broken, rhythmic brushstrokes of pure color to represent atmosphere, light and visual effects while depicting his immediate surroundings in Paris and nearby villages. During the next decade, his fortune began to improve as a result of a growing base of support from art dealers and collectors, both in Europe and the United States. By the mid-1880s, his paintings began to receive critical “Everyone discusses my acclaim. art and pretends to understand, as if it were By 1890, Monet was financially secure enough to purchase a house in Giverny, a rural town in Normandy. During these later years, Monet began painting the same subject over and over necessary to understand, again at different times of the day or year. These series paintings became some of his most when it is simply famous works and include views of the Siene River, the Thames River in London, Rouen necessary to love.” Cathedral, oat fields, haystacks and water lilies. -

Les Ornements De La Femme : L'éventail, L'ombrelle, Le Gant, Le Manchon (Ed

Les ornements de la femme : l'éventail, l'ombrelle, le gant, le manchon (Ed. complète et définitive) / par Octave Uzanne Source gallica.bnf.fr / Bibliothèque nationale de France Uzanne, Octave (1851-1931). Auteur du texte. Les ornements de la femme : l'éventail, l'ombrelle, le gant, le manchon (Ed. complète et définitive) / par Octave Uzanne. 1892. 1/ Les contenus accessibles sur le site Gallica sont pour la plupart des reproductions numériques d'oeuvres tombées dans le domaine public provenant des collections de la BnF. Leur réutilisation s'inscrit dans le cadre de la loi n°78-753 du 17 juillet 1978 : - La réutilisation non commerciale de ces contenus ou dans le cadre d’une publication académique ou scientifique est libre et gratuite dans le respect de la législation en vigueur et notamment du maintien de la mention de source des contenus telle que précisée ci-après : « Source gallica.bnf.fr / Bibliothèque nationale de France » ou « Source gallica.bnf.fr / BnF ». - La réutilisation commerciale de ces contenus est payante et fait l'objet d'une licence. Est entendue par réutilisation commerciale la revente de contenus sous forme de produits élaborés ou de fourniture de service ou toute autre réutilisation des contenus générant directement des revenus : publication vendue (à l’exception des ouvrages académiques ou scientifiques), une exposition, une production audiovisuelle, un service ou un produit payant, un support à vocation promotionnelle etc. CLIQUER ICI POUR ACCÉDER AUX TARIFS ET À LA LICENCE 2/ Les contenus de Gallica sont la propriété de la BnF au sens de l'article L.2112-1 du code général de la propriété des personnes publiques. -

John SC Abbott and Self-Interested Motherhood

Capitalizing on Mother: John S.C. Abbott and Self-interested Motherhood CAROLYN J. LAWES She who was first in the transgression, must yet be the principal earthly instrument in the restoration. ... Oh mothers! reflect upon the power your Maker has placed in your hands. There is no earthly influence to be compared with yours God has constituted you the guardians and the controllers ofthe human family. John S.C. Abbott' N THE EARLY nineteenth century, middle-class Americans rushed to rehabilitate the image of women. New England's IPuritans had castigated women as the daughters of Eve, re- sponsible for the introduction of sin into the world and the damnation of humankind.^ But Americans ofthe late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries stood this analysis upon its head: The research for this article was generously supported by a Kate B. and Hall J. Peterson Fellowship at the American Antiquarian Society. The author also wishes to thank Scott E. Casper, David J. Garrow, Julie Goodson-Lawes, T'homas G. Knoles, Sandra Pryor, Caroline F. Sloat, Elizabeth Alice White, Karin Wulf, and the anonymous readers uf the manuscript for their invaluable advice and suppon. 1. John S.C. Abbott, The Mother at Home: Or, the Principles of Maternal Duty (Boston, 1^33)' I4ÍÍ-49- The Mother at Home 'io\á more than a quarter of a million copies and went through numerous editions and printings. 2. See. far example. Mary Maples Dunn, 'Saints and Sisters: Congregational and Quaker Women in the Early Colonial Period,' in Janet Wilson James, ed.. Women in Avu-7ican Religion (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1980): 27-46; Lonna M. -

NEO-Orientalisms UGLY WOMEN and the PARISIAN

NEO-ORIENTALISMs UGLY WOMEN AND THE PARISIAN AVANT-GARDE, 1905 - 1908 By ELIZABETH GAIL KIRK B.F.A., University of Manitoba, 1982 B.A., University of Manitoba, 1983 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (Department of Fine Arts) We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA . October 1988 <£> Elizabeth Gail Kirk, 1988 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of Fine Arts The University of British Columbia 1956 Main Mall Vancouver, Canada V6T 1Y3 Date October, 1988 DE-6(3/81) ABSTRACT The Neo-Orientalism of Matisse's The Blue Nude (Souvenir of Biskra), and Picasso's Les Demoiselles d'Avignon, both of 1907, exists in the similarity of the extreme distortion of the female form and defines the different meanings attached to these "ugly" women relative to distinctive notions of erotic and exotic imagery. To understand Neo-Orientalism, that is, 19th century Orientalist concepts which were filtered through Primitivism in the 20th century, the racial, sexual and class antagonisms of the period, which not only influenced attitudes towards erotic and exotic imagery, but also defined and categorized humanity, must be considered in their historical context. -

Futurism-Anthology.Pdf

FUTURISM FUTURISM AN ANTHOLOGY Edited by Lawrence Rainey Christine Poggi Laura Wittman Yale University Press New Haven & London Disclaimer: Some images in the printed version of this book are not available for inclusion in the eBook. Published with assistance from the Kingsley Trust Association Publication Fund established by the Scroll and Key Society of Yale College. Frontispiece on page ii is a detail of fig. 35. Copyright © 2009 by Yale University. All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers. Designed by Nancy Ovedovitz and set in Scala type by Tseng Information Systems, Inc. Printed in the United States of America by Sheridan Books. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Futurism : an anthology / edited by Lawrence Rainey, Christine Poggi, and Laura Wittman. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-300-08875-5 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Futurism (Art) 2. Futurism (Literary movement) 3. Arts, Modern—20th century. I. Rainey, Lawrence S. II. Poggi, Christine, 1953– III. Wittman, Laura. NX456.5.F8F87 2009 700'.4114—dc22 2009007811 A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48–1992 (Permanence of Paper). 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 CONTENTS Acknowledgments xiii Introduction: F. T. Marinetti and the Development of Futurism Lawrence Rainey 1 Part One Manifestos and Theoretical Writings Introduction to Part One Lawrence Rainey 43 The Founding and Manifesto of Futurism (1909) F. -

Number 25 Update

NUMBER 25 UPDATE CLICK HERE TO FIND THE LATEST NEWS W ΔΓ David Ghezelbash Archéologie EXHIBITION ANCIENT WORKS OF ART FROM THE MEDITERRANEAN SEA At the Galerie David Ghezelbash 12 rue Jacob TO 75006 Paris France 04/26/2013 Mobile + 33 (0)6 88 23 39 11 [email protected] FROM www.davidghezelbash.com 06/01/2013 BID AT WWW.DROUOTLIVE.COM FREE SERVICE AND WITHOUT EXTRA FEES BID AT DROUOT ANYWHERE ! LA GAZETTE DROUOT INTERNATIONAL WWW.GAZETTE-INTERNATIONAL.CN PARIS - NICE ACROSS THE ORIENT Important fragment of the torso of a General of the Delta, gouverner of de Upper Egypt named Psamtik. Greywacke. Egypt, 30th dynasty, 4th century BC. H. 63 cm Remained in Private French collection since 1906. WEDNESDAY 5 JUNE 2013 DROUOT Experts: Archeology: Daniel LEBEURRIER - Islam: Alexis RENARD 1, rue de la Grange-Batelière - 75009 Paris - Tel. +33.(0)1.47.70.81.36 - Fax : +33.(0)1.42.47.05.84 - Site : www.boisgirard.com - E-mail : [email protected] Authorised auctioneers : Isabelle Boisgirard et Pierre-Dominique Antonini - N° agrément 2001-022 THE MAGAZINE CONTENTS CONTENTS ART MARKET - MAGAZINE 68 RESULTS Recent bids have included a large number of world records, not only for Old Masters (dominated by Jacobus Vrel), but also for contemporary artists like Adami – not to mention drawing, a distinctly French speciality! MEETING 124 In two decades, Bill Pallot, the most talked- about antique dealer in the media, has built up a collection that may be highly disparate at first glance, but is truly fascinating. We explore this cabinet of curiosities. -

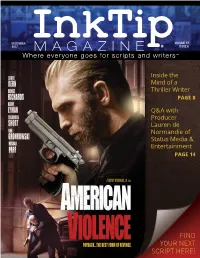

MAGAZINE ® ISSUE 6 Where Everyone Goes for Scripts and Writers™

DECEMBER VOLUME 17 2017 MAGAZINE ® ISSUE 6 Where everyone goes for scripts and writers™ Inside the Mind of a Thriller Writer PAGE 8 Q&A with Producer Lauren de Normandie of Status Media & Entertainment PAGE 14 FIND YOUR NEXT SCRIPT HERE! CONTENTS Contest/Festival Winners 4 Feature Scripts – FIND YOUR Grouped by Genre SCRIPTS FAST 5 ON INKTIP! Inside the Mind of a Thriller Writer 8 INKTIP OFFERS: Q&A with Producer Lauren • Listings of Scripts and Writers Updated Daily de Normandie of Status Media • Mandates Catered to Your Needs & Entertainment • Newsletters of the Latest Scripts and Writers 14 • Personalized Customer Service • Comprehensive Film Commissions Directory Scripts Represented by Agents/Managers 40 Teleplays 43 You will find what you need on InkTip Sign up at InkTip.com! Or call 818-951-8811. Note: For your protection, writers are required to sign a comprehensive release form before they place their scripts on our site. 3 WHAT PEOPLE SAY ABOUT INKTIP WRITERS “[InkTip] was the resource that connected “Without InkTip, I wouldn’t be a produced a director/producer with my screenplay screenwriter. I’d like to think I’d have – and quite quickly. I HAVE BEEN gotten there eventually, but INKTIP ABSOLUTELY DELIGHTED CERTAINLY MADE IT HAPPEN WITH THE SUPPORT AND FASTER … InkTip puts screenwriters into OPPORTUNITIES I’ve gotten through contact with working producers.” being associated with InkTip.” – ANN KIMBROUGH, GOOD KID/BAD KID – DENNIS BUSH, LOVE OR WHATEVER “InkTip gave me the access that I needed “There is nobody out there doing more to directors that I BELIEVE ARE for writers than InkTip – nobody. -

Camille on Her Deathbed

ART AND IMAGES IN PSYCHIATRY SECTION EDITOR: JAMES C. HARRIS, MD Camille on Her Deathbed AMILLE-LEONIE DONCIEUX Monet (1847- Many years after Camille’s passing, Monet spoke with 1879) died at 32 years of age after a pro- his friend Georges Clemenceau, the former French prime tracted illness, most likely metastatic cer- minister, about her death: vical cancer.1 She had been the inspiration and model for her husband, Claude Mo- I found myself staring at the tragic countenance, automatically trying to identify the sequence, the proportion of light and shade Cnet (1840-1926). In 1866, despite his youth, Monet’s in the colors that death had imposed on the immobile face. painting of Camille (Woman in Green Dress) was ac- Shades of blue, yellow, gray...Even before the thought oc- cepted and acclaimed at the annual Paris Salon, the con- curred to memorize the face that meant so much to me, my first servative arbiter of subject matter and style in painting.2 involuntary reflex was to tremble at the shock of the colors. In In the ensuing 12 years, Camille, either alone or with her spite of myself, my reflexes drew me into the unconscious op- son, was the primary model for his paintings. eration that is the daily order of my life. Pity me, my friend.4 Their relationship began when she was just 19 years of age and he was 25. She was said to be attractive and in- These comments were made 40 years after Camille’s telligent with beautiful eyes. During their life together she death. -

1 Figures of Ubicomp: Conceptualizing And

FIGURES OF UBICOMP: CONCEPTUALIZING AND COMPOSING ACTIONABLE MEDIA By JOHN TINNELL A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2013 1 © 2013 John Tinnell 2 To Hutton 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like thank all of the amazing people in the English Department at the University of Florida, especially Greg Ulmer and Sid Dobrin. Greg’s work models everything I hope to achieve in my own. While I try to not follow his footsteps too obviously, I will always be seeking to further the insights and projects that his books so originally present. For me, Greg is among the masters that his motto gestures toward. Sid, perhaps more than anyone else, helped me come of age as a professional. Because of his constant encouragement and pinpoint advice, I felt as though I had made the transition from graduate student to Assistant Professor before I even started my dissertation. It would have been inconceivable for me to complete this project in under a year without that level of confidence and support. The other two members of my committee, Laurie Gries and Jack Stenner, provided me with vital feedback. Laurie’s capacity to respond to her students’ writing is unparalleled; she saw incongruencies in my writing to which I would otherwise still be blind. Jack voiced criticisms that I did not want to hear, which are the most important to hear. I thank my parents, emphatically, for their support and for doing what they are passionate about and always encouraging me to do the same. -

Crystal Thomas Art History Paper Impressionism Through the Eyes Of

Crystal Thomas Art History Paper Impressionism through the eyes of Edouard Manet and Claude Monet Impressionism is a movement that had a major impact in France during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. There is no exact date for the beginning of this movement. Louis Leroy, an art critic, gave this period its name when he went to an independent exhibition and came across Claude Monet's Sunrise. He said it looked impressionistic, meaning not finished. Impressionists liked to be called Independents. During this time, being called an Impressionist was not a good thing. Impressionistic works were not accepted in the world of art at this time, and art critics were referring to these painters as being lazy. Most of the public did not support Impressionism. People wondered why the artists were not finishing their brush strokes and they did not like the colors being used. Among some of the Impressionist painters are Claude Monet, Edouard Manet, Edgar Degas, Pierre Auguste Renoir, Paul Cezanne, and Camille Pisarro. Characteristics of this movement include noticeable brush strokes that are not blended together, applying the paint in a thick, impasto style, and mixing the colors right on the canvas. Some Impressionists like to take an optical approach to painting and place the hues right next to each other on the canvas. This allows the eyes to do the mixing. Optical color mixing makes paintings look lighter than if the colors were mixed, and gives the paintings the effect of being in motion. Impressionists were interested in painting the everyday world around them.