Dara Shikoh's Dream of Translating Prince to Philosopher

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mughal Paintings of Hunt with Their Aristocracy

Arts and Humanities Open Access Journal Research Article Open Access Mughal paintings of hunt with their aristocracy Abstract Volume 3 Issue 1 - 2019 Mughal emperor from Babur to Dara Shikoh there was a long period of animal hunting. Ashraful Kabir The founder of Mughal dynasty emperor Babur (1526-1530) killed one-horned Department of Biology, Saidpur Cantonment Public College, rhinoceros and wild ass. Then Akbar (1556-1605) in his period, he hunted wild ass Nilphamari, Bangladesh and tiger. He trained not less than 1000 Cheetah for other animal hunting especially bovid animals. Emperor Jahangir (1606-1627) killed total 17167 animals in his period. Correspondence: Ashraful Kabir, Department of Biology, He killed 1672 Antelope-Deer-Mountain Goats, 889 Bluebulls, 86 Lions, 64 Rhinos, Saidpur Cantonment Public College, Nilphamari, Bangladesh, 10348 Pigeons, 3473 Crows, and 10 Crocodiles. Shahjahan (1627-1658) who lived 74 Email years and Dara Shikoh (1657-1658) only killed Bluebull and Nur Jahan killed a tiger only. After study, the Mughal paintings there were Butterfly, Fish, Bird, and Mammal. Received: December 30, 2018 | Published: February 22, 2019 Out of 34 animal paintings, birds and mammals were each 16. In Mughal pastime there were some renowned artists who involved with these paintings. Abdus Samad, Mir Sayid Ali, Basawan, Lal, Miskin, Kesu Das, Daswanth, Govardhan, Mushfiq, Kamal, Fazl, Dalchand, Hindu community and some Mughal females all were habituated to draw paintings. In observed animals, 12 were found in hunting section (Rhino, Wild Ass, Tiger, Cheetah, Antelope, Spotted Deer, Mountain Goat, Bluebull, Lion, Pigeon, Crow, Crocodile), 35 in paintings (Butterfly, Fish, Falcon, Pigeon, Crane, Peacock, Fowl, Dodo, Duck, Bustard, Turkey, Parrot, Kingfisher, Finch, Oriole, Hornbill, Partridge, Vulture, Elephant, Lion, Cow, Horse, Squirrel, Jackal, Cheetah, Spotted Deer, Zebra, Buffalo, Bengal Tiger, Camel, Goat, Sheep, Antelope, Rabbit, Oryx) and 6 in aristocracy (Elephant, Horse, Cheetah, Falcon, Peacock, Parrot. -

Later Mughals;

1 liiu} ijji • iiiiiiimmiiiii ii i] I " • 1 1 -i in fliiiiiiii LATER MUGHALS WILLIAM IRVINE, i.c.s. (ret.), Author of Storia do Mogor, Army of the Indian Moguls, &c. Edited and Augmented with The History of Nadir Shah's Invasion By JADUNATH SARKAR, i.e.s., Author of History of Aurangzib, Shivaji and His Times, Studies in Mughal India, &c. Vol. II 1719—1739 Calcutta, M. C. SARKAR & SONS, 1922. Published by C. Sarkar o/ M. C. Sarkar & Sons 90 /2A, Harrison Road, Calcutta. Copyright of Introductory Memoir and Chapters XI—XIII reserved by Jadunath Sarkar and of the rest of the book by Mrs. Margaret L. Seymour, 195, Goldhurst Terrace, London. Printer : S. C. MAZUMDAR SRI GOURANGA PRESS 71/1, Mirzapur Street, Calcutta. 1189/21. CONTENTS Chapter VI. Muhammad Shah : Tutelage under the Sayyids ... 1—101 Roshan Akhtar enthroned as Md. Shah, 1 —peace made with Jai Singh, 4—campaign against Bundi, 5—Chabela Ram revolts, 6—dies, 8—Girdhar Bahadur rebels at Allahabad, 8—fights Haidar Quli, 11 —submits, 15—Nizam sent to Malwa, 17—Sayyid brothers send Dilawar Ali against him, 19— Nizam occupies Asirgarh and Burhanpur, 23—battle with Dilawar Ali at Pandhar, 28—another account of the battle, 32—Emperor's letter to Nizam, 35—plots of Sayyids against Md. Amin Khan, 37—Alim Ali marches against Nizam, 40—his preparations, 43—Nizam's replies to Court, 45—Alim Ali defeated at Balapur, 47—Emperor taken towards Dakhin, 53—plot of Md. Amin against Sayyid Husain Ali, 55—Husain Ali murdered by Haidar Beg, 60—his camp plundered, 61 —his men attack Emperor's tents, 63—Emperor's return towards Agra, 68—letters between Md. -

Cultural Festivals: an Impotent Source of De-Radicalization Process in Pakistan: a Case Study of Urs Ceremonies in Lahore City

Journal of the Punjab University Historical Society Volume No. 03, Issue No. 2, July - December 2017 Syed Ali Raza* Cultural Festivals: An Impotent Source of De-Radicalization Process in Pakistan: A Case Study of Urs Ceremonies in Lahore City Abstract The Sufism has unique methodology of the purification of consciousness which keeps the soul alive. The natural corollary of its origin and development brought about religo-cultural changes in Islam which might be different from the other part of Muslim world. Sufism has been explained by many people in different ways and infect is the purification of the heart and soul as prescribed in the holy Quran by God. They preach that we should burn our hearts in the memory of God. Our existence is from God which can only be comprehended with the help of blessing of a spiritual guide in the popular sense of the world. Sufism is the way which teaches us to think of God so much that we should forget our self. Sufism is the made of religious life in Islam in which the emphasis is placed, not on the performance of external ritual but on the activities of the inner-self’ in other words it signifies Islamic mysticism. Beside spirituality, the Sufi’s contributed in the promotion of performing art, particularly the music. Pakistan has been the center of attraction for the Sufi Saints who came from far-off areas like Iran, Iraq, Afghanistan and Arabia. The people warmly welcomes them, followed their traditions and preaching’s and even now they celebrates their anniversaries in the form of Urs. -

Zaheeruddin V. State and the Official Persecution of the Ahmadiyya Community in Pakistan

Minnesota Journal of Law & Inequality Volume 14 Issue 1 Article 5 June 1996 Enforced Apostasy: Zaheeruddin v. State and the Official Persecution of the Ahmadiyya Community in Pakistan M. Nadeem Ahmad Siddiq Follow this and additional works at: https://lawandinequality.org/ Recommended Citation M. N. Siddiq, Enforced Apostasy: Zaheeruddin v. State and the Officialersecution P of the Ahmadiyya Community in Pakistan, 14(1) LAW & INEQ. 275 (1996). Available at: https://scholarship.law.umn.edu/lawineq/vol14/iss1/5 Minnesota Journal of Law & Inequality is published by the University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing. Enforced Apostasy: Zaheeruddin v. State and the Official Persecution of the Ahmadiyya Community in Pakistan M. Nadeem Ahmad Siddiq* Table of Contents Introduction ............................................... 276 I. The Ahmadiyya Community in Islam .................. 278 II. History of Ahmadis in Pakistan ........................ 282 III. The Decision in Zaheerudin v. State ................... 291 A. The Pakistan Court Considers Ahmadis Non- M uslim s ........................................... 292 B. Company and Trademark Laws Do Not Prohibit Ahmadis From Muslim Practices ................... 295 C. The Pakistan Court Misused United States Freedom of Religion Precedent .............................. 299 D. Ordinance XX Should Have Been Found Void for Vagueness ......................................... 314 E. The Pakistan Court Attributed False Statements to Mirza Ghulam Almad ............................. 317 F. Ordinance XX Violates -

Beyond 'Tribal Breakout': Afghans in the History of Empire, Ca. 1747–1818

Beyond 'Tribal Breakout': Afghans in the History of Empire, ca. 1747–1818 Jagjeet Lally Journal of World History, Volume 29, Number 3, September 2018, pp. 369-397 (Article) Published by University of Hawai'i Press DOI: https://doi.org/10.1353/jwh.2018.0035 For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/719505 Access provided at 21 Jun 2019 10:40 GMT from University College London (UCL) Beyond ‘Tribal Breakout’: Afghans in the History of Empire, ca. 1747–1818 JAGJEET LALLY University College London N the desiccated and mountainous borderlands between Iran and India, Ithe uprising of the Hotaki (Ghilzai) tribes against Safavid rule in Qandahar in 1717 set in motion a chain reaction that had profound consequences for life across western, south, and even east Asia. Having toppled and terminated de facto Safavid rule in 1722,Hotakiruleatthe centre itself collapsed in 1729.1 Nadir Shah of the Afshar tribe—which was formerly incorporated within the Safavid political coalition—then seized the reigns of the state, subduing the last vestiges of Hotaki power at the frontier in 1738, playing the latter off against their major regional opponents, the Abdali tribes. From Kandahar, Nadir Shah and his new allies marched into Mughal India, ransacking its cities and their coffers in 1739, carrying treasure—including the peacock throne and the Koh-i- Noor diamond—worth tens of millions of rupees, and claiming de jure sovereignty over the swathe of territory from Iran to the Mughal domains. Following the execution of Nadir Shah in 1747, his former cavalry commander, Ahmad Shah Abdali, rapidly established his independent political authority.2 Adopting the sobriquet Durr-i-Durran (Pearl of 1 Rudi Matthee, Persia in Crisis. -

Shah Jahan) Supported by His Father-In- Law, Asaf Khan Rebelled Against Jahangir

Ghiasuddin Balban (1266– 86 C.E.) ØHe was slave of Iltumish. ØHe was one of the prominent members of the Chalgani created by Iltutmish. ØHis major challenge was from the Chalgani (The Forty) so through overt (putting down the rebellions) & covert operations (Sijda, Paibos) he liquidated them. ØBalban’s policy was of Blood & Iron, this made him a despot. Continued.. ØHe propounded the Divine Right Theory of Kingship as he considered himself the Vice Royalty of God on Earth. ØHe described himself as Zil-i-Ilahi (shadow of God on Earth) in his coins. ØHe traced his descent to the Mythical Turkish hero Afrasiyab. ØHe introduced several Persian customs such as Sijda (prostration to the king) and Paibos (Kissing of king’s feet) ØPersian Calendar & Persian festival of Nauroz was introduced by him. ØBalban patronized Amir Khusrau (The parrot of India). ØHe established a separate military department Diwan-i-Arz & reorganized the army. ØHe also appointed spies to check the activities of the nobles. ØBalban’s rule saw the restoration of law & order around Delhi. ØEarlier the Mewathis often plundered its outskirts, so, Balban went down heavily on them & restored order thus the roads became safe for travel. End ØBalban groomed his son prince Muhammad to be his successor but the latter was killed in a battle against Mongols in the North-West. ØBalban died in 1287 C.E., nominating Kai Khusrau, his grandson to be the next Sultan but he was over looked & Kaikubad, other grandson of Balban was placed in the throne but he was incompetent & this led Jaluluddin Khilji, to occupy Delhi by a military coup in 1290 C.E. -

Reimagining the Role of Mian Muhamad Mumtaz Daultana in Colonial and Post-Colonial Punjab

Journal of the Research Society of Pakistan Volume No. 57, Issue No. 1 (January – June, 2020) Farzanda Aslam * Muhamad Iqbal Chawla ** Zabir Saeed *** Moazzam Wasti **** Forgotten soldier of Pakistan Movement: Reimagining the role of Mian Muhamad Mumtaz Daultana in Colonial and Post-colonial Punjab Abstract Plethora of works have been produced on the colonial and post-colonial history of the Punjab but the role of Mian Muhammad Mumtaz Daultana has been academically overnighted by the historians to date and this paper intends to address it. He was an important leader of the Punjab who remained committed to the Pakistan movement, remained loyal and worked hard under the leadership of Quaid-i-Azam in the creation and consolidation of Pakistan. He was president of the Punjab Muslim League and also the first chief Minister of Pakistani Punjab. Therefore it is of immense importance to understand the role of Mian Muhammad Mumtaz Daultana in the creation and consolidation of Pakistan in the light of primary and secondary sources. Before the inception of Pakistan, his father Ahmad Yar Daultana was a popular politician from the Daultana family in the Punjab region. His house was the focal point for important political activities. Daultana was selected by Quaid-i- Azam to contend on behalf of the Muslim League against the Unionist Party because this party was not in favour of the Muslim League, by looking for the certainty of the Mumtaz Daultana, Quaid-i-Azam made him the individual from the member of Direct-action committee. The other member of the committee was ministers of the Muslim League s’ parliamentary and interim government. -

Module 3 Shah Jahan and Aurangzeb Who Was the Successor of Jahangir

Module 3 Shah Jahan and Aurangzeb Who was the successor of Jahangir? Who was the last most power full ruler in the Mughal dynasty? What was the administrative policy of Aurangzeb? The main causes of Downfall of Mughal Empire. Shah Jahan was the successor of Jahangir and became emperor of Delhi in 1627. He followed the policy of his ancestor and campaigns continued in the Deccan under his supervision. The Afghan noble Khan Jahan Lodi rebelled and was defeated. The campaigns were launched against Ahmadnagar, The Bundelas were defeated and Orchha seized. He also launched campaigns to seize Balkh from the Uzbegs was successful and Qandhar was lost to the Safavids. In 1632Ahmadnagar was finally annexed and the Bijapur forces sued for peace. Shah Jahan commissioned the Taj Mahal. The Taj Mahal marks the apex of the Mughal Empire; it symbolizes stability, power and confidence. The building is a mausoleum built by Shah Jahan for his wife Mumtaz and it has come to symbolize the love between two people. Jahan's selection of white marble and the overall concept and design of the mausoleum give the building great power and majesty. Shah Jahan brought together fresh ideas in the creation of the Taj. Many of the skilled craftsmen involved in the construction were drawn from the empire. Many also came from other parts of the Islamic world - calligraphers from Shiraz, finial makers from Samrkand, and stone and flower cutters from Bukhara. By Jahan's period the capital had moved to the Red Fort in Delhi. Shah Jahan had these lines inscribed there: "If there is Paradise on earth, it is here, it is here." Paradise it may have been, but it was a pricey paradise. -

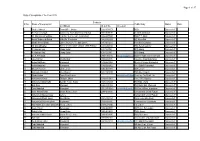

Of 17 Data of Complaints of the Year 2015 (I) Address (II) Cell No

Page 1 of 17 Data of Complaints of the Year 2015 Contacts Sr No. Name of Complainant Public Body Status Date (i) Address (II) Cell No (iii) e-mail 1 Shakeel Ahmad Dawn Office, Multan 0333-8558057 DCO Disposed off 2 Dr. Farooq Lahgah Gulraiz Cly. Allah Shafi Chwok Multan 0302-8699035 Heald Deptt Multan Disposed off 3 Ch. Muhammad Saddique H # 788, St # 16, I-8/2, Aslamabad 0306-4977944 DCO T.T. Singh Disposed off 4 Hamid Mahmood Shahid Millta Rd. Faisalabad 033-26762069 MD Wasa Fbd Disposed off 5 Bashir Ahmad Bhatti Lahore Museum, The Mall Lahore 0347-4001211 Print Media Cmpany Disposed off 6 Mir Ahmad Qamar Ali Pur Chowk, Bazar Jampur, Distt. Rajinpur 0333-6452838 TMA Tehsil Jaampur Disposed off 7 M. Kamran Saqi Jhang Sadar 301-4124790 DPO Jhang Disposed off 8 M. Kamran Saqi Jhang Sadar 301-4124790 DPO Jhang Disposed off 9 Dr. A. H. Nayyar 0300-5360110 [email protected] solar Power Ltd Disposed off 10 Javed Akhtar Muzafarghar 0300-6869185 Executive Engg Muzafargar Disposed off 11 Arslan Muzzamil Rawalpindi 0312-5641962 Director Colleges Rawalpindi Disposed off 12 Arslan Muzzamil Rawalpindi 0312-5641962 Prin. GGHS Rawalpindi Disposed off 13 Ghulam Hussain UET, Lahore 0300-4533915 UET Lahore Disposed off 14 Muhammad Arshad Muzaffargarr 0302-8941374 TMA Muzaffargarh Disposed off 15 Shahid Aslam Davis Road, Lahore shahidaslam81@gmaiSecretary Fin. Deptt. Lhr Disposed off 16 Muhammad Yonus Dipalpur, Okara 0313-9151351 Princ. DPS, Dipalpur Disposed off 17 Muhammad Afzal Kathi Satellite Town, Jhang 0345-3325269 PIO TMA, Jhang Disposed off 18 Ejaz Nasir Khaniwal 0323-3335332 PIO, Baitul Mall, Khanewal Disposed off 19 Zahid Abdullah Islamabad 051-2375158-9 [email protected] Stat. -

Beliefs and Behaviors of Shrine Visitors of Bibi Pak Daman

Journal of Gender and Social Issues Spring 2020, Vol. 19, Number 1 ©Fatima Jinnah Women University, Rawalpindi Beliefs and Behaviors of Shrine Visitors of Bibi Pak Daman Abstract The present study aims at focusing on what kind of beliefs are associated with the shrine visits that make them visitors believe and behave in a specific way. The shrine selected for this purpose was Bibi Pak Daman, Lahore, Pakistan. The visitors of this shrine were observed using non- participant observation method. Field notes were used to record observations and the data were analyzed using thematic analysis. Three major themes emerged out of the data. The first major theme of immortality appeared with sub-themes of belief in existence after death, belief in supernatural powers of chaste ladies and objects placed at the shrine. The second theme that emerged consisted of superstitions with the sub-themes of superstitions related to objects and miracles/mannat system. The third theme that emerged was of the beliefs in the light of the placebo effect and the sub-themes included prayer fulfillment, enhanced spirituality and problem resolution. Keywords: Bibi Pak Daman, beliefs, shrine visitors INTRODUCTION Islam has a unique role in meeting the spiritual needs of its followers through Sufism, which is defined as a system of beliefs wherein Muslims search for their spiritual knowledge in the course of direct personal experience and practice of Allah Almighty (Khan & Sajid, 2011). Sufism represents the spiritual dimension of Islam. Sufis played a major role in spreading Islam throughout the sub-continent, sometimes even more than the warriors. In early 12th century, Sufi saints connected the Hindus and Muslims with their deep devotion and love for God as the basic tenet of belief. -

Forestry in the Princely State of Swat and Kalam (North-West Pakistan)

Forestry in the Princely State of Swat and Kalam (North-West Pakistan) A Historical Perspective on Norms and Practices IP6 Working Paper No.6 Sultan-i-Rome, Ph.D. 2005 Forestry in the Princely State of Swat and Kalam (North-West Pakistan) A Historical Perspective on Norms and Practices IP6 Working Paper No.6 Sultan-i-Rome, Ph.D. 2005 The Swiss National Centre of Competence in Research (NCCR) North-South is based on a network of partnerships with research institutions in the South and East, focusing on the analysis and mitigation of syndromes of global change and globalisation. Its sub-group named IP6 focuses on institutional change and livelihood strategies: State policies as well as other regional and international institutions – which are exposed to and embedded in national economies and processes of globalisation and global change – have an impact on local people's livelihood practices and strategies as well as on institutions developed by the people themselves. On the other hand, these institutionally shaped livelihood activities have an impact on livelihood outcomes and the sustainability of resource use. Understanding how the micro- and macro-levels of this institutional context interact is of vital importance for developing sustainable local natural resource management as well as supporting local livelihoods. For an update of IP6 activities see http://www.nccr-north-south.unibe.ch (>Individual Projects > IP6) The IP6 Working Paper Series presents preliminary research emerging from IP6 for discussion and critical comment. Author Sultan-i-Rome, Ph.D. Village & Post Office Hazara, Tahsil Kabal, Swat–19201, Pakistan e-mail: [email protected] Distribution A Downloadable pdf version is availale at www.nccr- north-south.unibe.ch (-> publications) Cover Photo The Swat Valley with Mingawara, and Upper Swat in the background (photo Urs Geiser) All rights reserved with the author. -

June 2019 Question Paper 01 (PDF, 3MB)

Cambridge Assessment International Education Cambridge Ordinary Level BANGLADESH STUDIES 7094/01 Paper 1 History and Culture of Bangladesh May/June 2019 1 hour 30 minutes Additional Materials: Answer Booklet/Paper *0690022029* READ THESE INSTRUCTIONS FIRST An answer booklet is provided inside this question paper. You should follow the instructions on the front cover of the answer booklet. If you need additional answer paper ask the invigilator for a continuation booklet. Answer three questions. Answer Question 1 and two other questions. You are advised to spend about 30 minutes on each question. The number of marks is given in brackets [ ] at the end of each question or part question. This document consists of 9 printed pages and 3 blank pages. 06_7094_01_2019_1.2 © UCLES 2019 [Turn over 2 You must answer all parts of Question 1. 1 The Culture and Heritage of Bangladesh You are advised to spend about 30 minutes on this question. (a) This question tests your knowledge. (i) Alaol was able to find work in the royal court of Arakan because: A he was well known as a poet B his father was well known by the court of Arakan C he was introduced to the people there by pirates D he had won a literary award [1] (ii) Scholars criticised Rabindranath Tagore because: A he wrote under a pen name B he did not focus on one subject C his poems were simple D he used colloquial language in his writing [1] (iii) Which of the following was not among Kazi Nazrul Islam’s accomplishments? A recording songs B painting pictures C creating stories D writing poems [1] (iv) Which of the following was written by Jasimuddin while he was a student? A Kabar (The Grave) B Rakhali (Shepherd) C Nakshi Kanthar Math D Bagalir Hashir Golpo [1] (v) Zainul Abedin’s paintings are known because of his use of which of the following characteristics? A Pastel colours B Circles C The black line D Symmetry [1] © UCLES 2019 06_7094_01_2019_1.2 3 (b) This question tests your knowledge and understanding.